Report Published June 13, 2017 · 20 minute read

Third Way on the Road in IL-17: Can you hear me now?

Jim Kessler & Luke Watson

In Washington, we often distill a place into one easily digestible soundbite. An ex-manufacturing town in Indiana represents economic decay. A suburban community near Philadelphia becomes a tense case of uneven gentrification. A vacation town in Florida serves as a microcosm for Obama-Obama-Trump studies.

But if we learned nothing else from the 2016 elections, we at least realized that there has to be a better way to take the pulse of the country. The Democratic Party and its standard bearers — the advocacy groups and think tanks (including Third Way) — made a mistake in believing that polling is synonymous with listening and actually being there. So, we decided to jettison the idea that all we needed to know could be learned from the comfort of our desks, and we decided to pack our bags and take our own listening tour.

As much as we hope that the stories we collect will positively impact public policy for the individuals that we speak with, the main purpose of our visits is to listen, not to sell. We’re not selling a party, a candidate, or our own policy ideas to anyone that we talk to. We begin each listening session with the same first question: “What’s it like to live here?” At the conclusion of each trip, we will write a short summary in the effort to help everyone learn a bit more about the people who are choosing our elected leaders.

OUR FIRST VISIT: Illinois’s 17th Congressional District

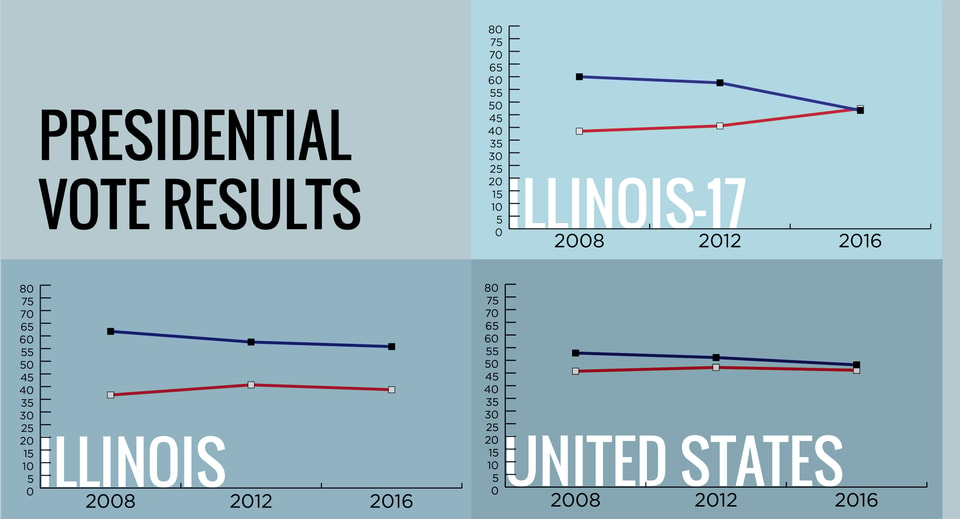

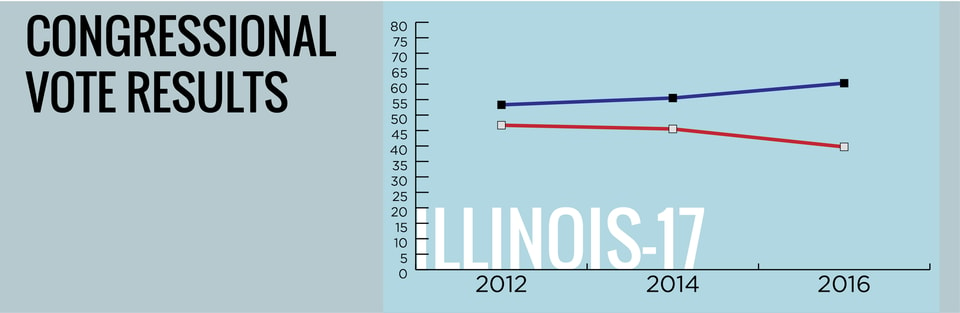

Our first trip was to Illinois’s 17th congressional district and the Quad Cities. IL-17 was chosen because voting behavior changed so dramatically, swinging 18 points from Obama to Trump. It went from the 139th most Democratic congressional district to 177th, according to the Cook Political Report.

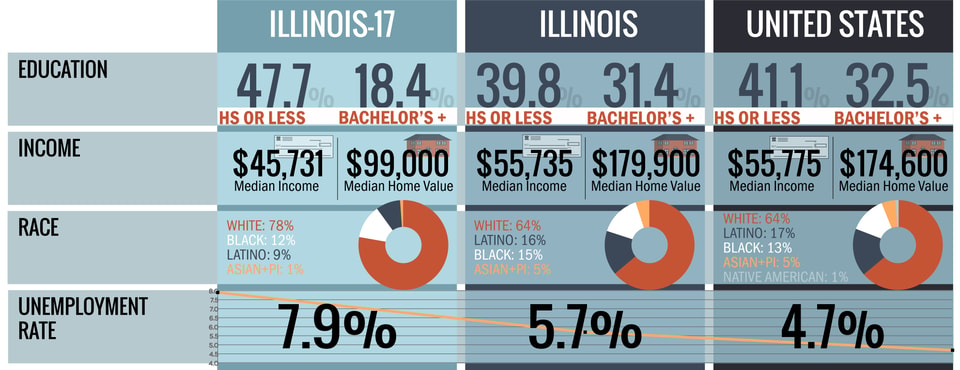

It’s predominantly white with median income and college degree attainment levels below the national average. In other words, it is the classic switcher district. All of the 11 counties that are entirely within IL-17 experienced population decline since 2000 (parts of Peoria, Rockford, and Tazewell are split between districts). The median income in each county is between $3,000 and $17,000 below the state’s. Trump outperformed Romney in each of the counties, ranging from 12 points in Stephenson County to 40 points in Henderson County. Nine of the 11 counties flipped from Obama to Trump — of the remaining two, one stayed Democratic and one stayed Republican.

We tried to capture the sentiments of the people we spoke to. The quotes are as verbatim as we could get them. Where appropriate, we denote when a comment came from a Trump or a Hillary supporter. But in most cases, we don’t have to — at least in IL-17, there wasn’t much difference in what they had to say.

THE QUAD CITIES: “A Great Place to Live”

Flying into Moline airport, we are struck by the vastness and beauty of the place. Green fields, trees, rolling hills, sprawling farmland, and streams and tributaries leading into the Mississippi elicit a sense of vitality.

Along the shores of the Mississippi are the Quad Cities: Moline, Davenport, Rock Island, Bettendorf, and East Moline (yes, there are five of them, but Quint Cities never really caught on). The district extends east of the river to Peoria and north to the Wisconsin border, altogether covering approximately 7,000 square miles.

IL-17 is a working class and predominantly white; it’s 78% white overall, though Peoria and Rockford have significant minority populations. Moline also has a sizable Hispanic population, West Africans, and a considerable number of Burmese refugees. It’s predominantly Catholic and Protestant, with two small Jewish and Muslim enclaves. The median income is $45,700, about $10,000 below the state and national medians.

But to those who live here, the Quad Cities is quintessentially Midwestern. An agronomist from Geneseo described it as “a Norman Rockwell, bedroom community. You have the comfort of less change,” she said. A local veteran in Moline said “the people are friendly and humble. People talk to each other.”

“You know people. You are part of Americana,” effused a professional woman who works in agricultural. “I wouldn’t live anywhere else,” said a female Vietnam Veteran who spent her entire civilian life in the area.

Between sips of coffee in a local Moline church, one man remarked that after he moved here years ago, “I felt my soul relax.” There is a “high quality of life on a human scale,” he added.

Its residents express a contentment with what they have in this jewel. A Davenport health care professional described the Quad Cities as “the land of enough. Enough theater, enough restaurants, enough outdoors.” “It’s convenient with a rural feel,” a young farmer and mother told us.

People frequently brought up the importance of family and how the area is an idyllic place to grow up. “It’s a great place to raise a family. The schools are good and we are grounded here,” a union worker told us. “People move away for the opportunity, but come back because it’s a good place to live.” Another union worker called it “a great place with a low cost of living, civic pride, low crime and near enough to Chicago and Des Moines.” Said another, “the quality of life is really good. We have downtown and we have rural.” “You know your neighbors and your kids’ teachers,” said a Galesburg woman. “We take care of each other,” said a Moline woman.

THE FUTURE: “God help ‘em.”

Just as everyone loved the Quad Cities, everyone also had a similar story of its recent past. It went something like this: getting a good paying job was as easy as falling out of a boat. John Deere, International Harvester, Alcoa, Maytag and many other factories populated the region.

But then, we were told, the Quad Cities was hit hard three times: the farm crisis in the 1980s, de-industrialization in the 1990s, and the recession of the last decade. Some of the factories that were longstanding bedrocks of the community left — either gone to Mexico, overseas, lost to technology, or just boarded up. Because of automation, a job that “once took ten folks may only take three,” said a union worker.

The new jobs don’t pay well enough to “own your home, a few cars, a little bit of travel, and have a spouse that can be at home when the kids are home,” as one veteran lamented.

Nearly everyone we spoke with was affected by the economic tides in some way, but most of their anxiety was felt not for themselves, but for the young people in their community. “If I were in high school today, I’d be scared shitless,” said a union worker. “There’s no opportunity and fewer jobs.”

“There’s less opportunity. The world economy, outsourcing, [and] technology all cost middle class jobs,” said another union leader who runs apprenticeship programs.

'My advice to children? Get out of Illinois,' a woman in the agriculture sector said.

The common refrain about the local youth is “there’s no future here,” as a union worker succinctly put it. “My advice to children? Get out of Illinois,” a woman in the agriculture sector said. “People aren’t optimistic. A lot of new businesses are video gaming parlors,” she added.

When thinking about the future here one veteran said, “God help ’em. I wouldn’t want to be raising kids here today. There’s no work.” Another veteran agreed, “I’m scared for my grandkids.”

A young Moline elementary school teacher talking about the parents of her young students, asked, “Some of the people I work with … how do they break the loop?”

The “good” jobs are being replaced by low-paying jobs. “The new jobs are in service,” said another veteran. “When you’re a server, you can’t afford to shop where you work.”

Rather than a ticket up, a four-year college degree is synonymous with a ticket out. “College is not the answer for a lot of people,” a longtime community leader told us in a Galesburg restaurant. “Part of the problem is that everyone pushes their kids to go to college,” a union leader said. Yet, those who do get a four-year degree go elsewhere for better jobs — an equally fraught scenario. “They will just move on to be successful,” a trades worker said.

They long to be able to do well where they are, not someplace else.

“People give up inside,” one veteran said. “There’s a decline of human dignity,” a Moline pastor said matter-of-factly. “The pain of people who have not benefited from globalization and technology is the root of this cold civil war.”

WHAT CHANGED? “The American Dream has been downsized”

Despite a few new restaurants and microbreweries, main street downtown whispered instead of hummed.

We could see that the transition from an economy that’s bedrock is manufacturing and agriculture to one where service jobs are taking their place is a hard adjustment. Good jobs at John Deere (or simply “Deere” as the locals say) or Alcoa are hard to come by; service jobs paying $8 an hour are not.

The first signs of change came during the 1980’s agriculture depression. The area shed eight percent of its population during that decade. The number of combines sold in 1985 dropped to 5,800 from 40,000 in the 1970’s.

The farm crisis eventually abated, but then came de-industrialization. Plants moved to lower price states, like Mississippi. Others moved to Mexico, China, or elsewhere. Like a dirge, “Maytag moved to Mexico” was repeated in our conversations, including the date of departure in September 2004, which felt to us akin to a date like December 7th. “Galesburg lost Maytag and now it’s a retirement community,” a union man told us — a version of a line heard over and over.

Then, in the midst of de-industrialization, came the Great Recession, driving unemployment up to 10.2 percent. Today, unemployment is around 7.9 percent, but the progress is partially due to the decline in workforce participation of an aging community and people moving away for other job opportunities.

“The pace of change is dizzying and it’s getting worse,” said a Moline pastor. “When I was young, it was easy to get a job. Now? No way,” a union worker told us. “We’re victims of outsourcing and the constant pressure to drive wages down,” another agreed. “Businesses aren’t tied to the community anymore,” said a retired veteran.

“What’s changed is that my trajectory and my kids’ trajectory is very different because we’ve traded high wage manufacturing for low wage service,” a Moline parent told us. “Automation and technology is as transformational as the Industrial Revolution. My youngest daughter went into nursing. Great, that won’t go away,” another Moline parent said. “Farms are bigger and manufacturing is smaller with non-union plants,” a farm professional shrugged.

“Maytag left after 100 years and destroyed the town. We’re always worried it could happen here, like what just happened with Caterpillar in Peoria,” a Moline man said as people around the table solemnly nodded.

TRADE AND IMMIGRATION: “It’s complicated.”

Trade has been a blessing and a curse to IL-17, and people spoke of it in both ways during the same conversation. A region built on international exports — farm equipment, the military, aluminum, farm products, and manufacturing machinery — understands its close connection to far-flung places around the world. “We need trade. We need markets,” a Geneseo woman who works in agriculture said.

Trade’s ambivalent effects on the region are evident. The Mississippi flows alongside the district and, with it, commerce. Freight rail is a constant reminder of products moving north and south along the BNSF Railway. Interstate highways populated with trucks bisect the region.

The reliance, though, on international markets — no matter how integral to the community — is often met with apprehension. “It’s complicated, because if you sell worldwide you have to be worldwide, but…we’ve made bad trade deals,” a veteran said. “NAFTA hurt manufacturing,” another chimed in.

While some blame NAFTA for the erosion of manufacturing, others see far more nuance. “NAFTA hurts us, but it’s exaggerated,” a longtime Moline resident told us. “Orion is thriving because of the agricultural economy and trade,” a farm professional said. A Galesburg farmer who otherwise was sympathetic to Donald Trump said he was “concerned about the Administration’s trade policy because that’s where the growth is.”

In general, those in agriculture saw trade positively and those in manufacturing communities saw it skeptically. “McLaughlin is closing down. It opened in 1905. It’s outsourcing and technology,” a union trades worker lamented.

The discussion of trade sometimes bled into immigration. Immigration, too, is a complicated issue. One person we spoke to poignantly said: “We’re not anti-immigrant, we’re anti-immigration.” Explaining further he said he had empathy for people looking for a better life but anger at a system that allowed illegal immigration to happen.

One person we spoke to poignantly said: 'We’re not anti-immigrant, we’re anti-immigration.'

“I would do the same as they did. The problem isn’t illegal immigrants, it’s the people that hire them,” a union worker said. Another worker talked of the construction trade. “In commercial construction, everyone is legal and the wages are fair. In residential, so many people are working under the table and many are illegal immigrants.” Added another, “When a factory moves to Mexico, it’s stealing hundreds of jobs; in construction, it’s one job at a time.”

Still, there is a belief that all are welcome here. A Moline church serves its long-time congregation and several hundred recent Burmese refugees. “There’s 100 languages in the schools. Diversity is a challenge but people are welcome,” one congregant said.

THEIR VOICE: “Is there a constituency for the softer voice?”

Standing by the railroad tracks outside Galesburg, the clickety-clack of the train and the wind over the soybean field is only occasionally interrupted by a passing pickup truck. This is a place where listening is just as important as talking. But that quiet and stillness has been mistaken for silent approval.

“When you reached out to talk to me, my first reaction was to say ‘No, I’m the wrong person. I’m not a leader here.’ Then I realized that if I said no, you would find someone else with a louder voice and the louder voices always get heard. The people here have quiet voices,” a Geneseo woman said as we sat downtown.

In a time when the loudest voices drown out the soft, the voices of the people here are often ignored, the locals say. “The coasts think we’re Jesusland or Dumbasfuckistan,” a Moline man joked as others nodded and laughed in the church community room where we all sat.

Whether the individuals we spoke to actually voted for Trump, they expressed sympathy — or at least a tacit understanding — for those who did. “The people who voted for Trump aren’t all stupid, racist, or bad. The centrists are getting wiped out,” a Moline man told us. “I understand why Trump was elected,” a Galesburg man said. “Because everyone hates government.”

People are tired of small groups dominating the discussion,” a Galesburg woman said. “We in the middle aren’t involved.

These same people who voted for Trump (or at least understand why people voted for Trump) don’t like his crass language and behavior. But they voted for him in spite of it, not because of it, and because they felt he listened to them. “People are tired of small groups dominating the discussion,” a Galesburg woman said. “We in the middle aren’t involved.”

“The vote was not based on race. No one listened to us,” a community leader, who made clear he supported Hillary, said. “We attach labels and reduce people,” a Moline pastor said. “The left calls anyone who disagrees with them a fascist,” a Moline Millennial, who was not a Trump supporter, said. “Too much labeling. ‘You hate women. You’re a racist,’” a Moline teacher, who was not a Trump supporter, agreed.

The Heartland is quieter,” one pastor said. “All of Quad Cities is the soft voice,” said a Galesburg man.

“There’s CNN and Fox. It’s a business, not a service,” a Trump supporter said. “The media feeds it. We have the condescending Rachel Maddow and the always awful Fox,” a Moline Hillary fan said.

“We have loud voices on the left and right and they are obstructionists. People like us who are trying to create jobs don’t have a chance,” a Galesburg Trump supporter shrugged. “From a farmer’s perspective, our voice is so small,” a young farm mother said.

A union worker said, “loud voices are heard too much. Quiet voices are in the background. I am a quiet voice.”

“Is there a constituency for the softer voice?” the Geneseo woman asked as we said our goodbyes.

THE VILLAIN: “The game.”

The frustration we heard from the people in the Quad Cities was palpable, but it wasn’t about greed. Their distrust of government is a product of their experiences. The Illinois government is so reviled that it was hard for us not to sneak a glance at each other each time participants let it rip about the incompetence, the corruption, and the arrogance of Springfield. The line, “Illinois hasn’t passed a budget in two years,” was mentioned so often we thought it must be part of every morning’s drive time radio.

“Our license plate should read ‘The Land of Governors Who Go to Prison,’” a woman in agriculture laughed.

To those we spoke to, failing government was not an abstraction. We heard about the twenty teachers laid off nearby because they didn’t have a budget. We heard about the money owed to the local community college that wasn’t reimbursed by the state. We heard about how no budget meant parents had to buy sports uniforms for their school kids on high school teams.

Springfield was reviled, but enmity toward Washington wasn’t far behind.

“How do you get politicians to care more about the people than themselves?” asked a Moline elementary school teacher. “The last time I was proud of my government was September 12th, 2001,” a Moline pastor said. “We needed to shock the pond,” one woman who likely supported Trump told us.

“People in the East think politics is just a game. It’s not a game. I want more seriousness in D.C.,” a Galesburg man said. “It’s just rhetoric with no thought,” a union worker said. “Both sides just communicate through ‘meme’ wars,” a Millennial said.

In the Quad Cities where a farm crisis, de-industrialization, and the recession weakened the foundation of the region, bad decisions or no decisions in Washington lead to job loss and economic decay.

“I was in Washington and the economy’s success there irked me. Washington is nothing more than a parasitic uncaring blob,” a Moline man said. “Politicians aren’t listening or talking to each other. Let’s play together nicely,” a female veteran said. “There’s too much division and polarization. They have to learn to work together,” a Galesburg woman advised. “I’m willing to compromise just to see anything get done,” another said.

There was a sense that along the coasts, where the economy is perceived to be breezing along, failure in Washington had no cost. But in the Quad Cities where a farm crisis, de-industrialization, and the recession weakened the foundation of the region, bad decisions or no decisions in Washington lead to job loss and economic decay. Everyone here has some skin in the game where the success and failure of the community is concerned. “Why isn’t that true for the folks in the government?” One woman asked.

THE HEROES: “This area couldn’t do without them.”

John Deere is a massive company and it is adored in the Quad Cities. There is a Deere museum in Moline with giant farm equipment that kids can climb into. The company funds local charities and community events. “It’s fashionable to beat up on the big companies, but they provided all the good jobs,” a community leader told us.

“John Deere executives live here and are part of the community,” a woman who works in agriculture told us. The company is a “good employer, community partner, [and a] habitual sponsor,” a union trades leader said. “John Deere, Alcoa, Arsenal … those big businesses are good. Not all are good, but they are,” a Galesburg resident said. A veteran issued the one caveat we heard, “John Deere’s a good guy, but they can be a hard-ass.”

This good corporate behavior is paid back in loyalty by the people that work and live in the Quad Cities. People sport John Deere hats and shirts with pride, and speak affectionately of the company. That’s also the way people felt about Caterpillar until they announced their move from Peoria to Chicago. “If you work for Caterpillar you bleed yellow,” we were told. “Then they moved.”

The other heroes we heard again and again were the community colleges. Whereas a four-year college degree “means debt” and young people leaving the region, to many in IL-17, community colleges are seen as “the ticket,” as one union worker put it.

“This area couldn’t do without them,” a veteran said echoing a sentiment heard among nearly all of our people.

We sat with two Blackhawk Community College leaders to find out why everyone raved about the school.

“We start with the outcome, which is to provide companies with employees that they think are great. So we customize to business. We make a product customized to their needs,” the head of job training told us. She further explained, “We get a contract to train several dozen people for a specific company. I’ll meet with company management to find out what skills we need to teach. Then I’ll go to the plant floor because you’ll hear a different perspective from those actually doing the job. After that, we create a curriculum and find the right teacher. Not everyone is a good teacher, so we pay attention to who can teach it well,” she said.

“We have tough standards here because we’re doing them no favors if they can’t get a job or get fired,” she added. “We help our graduates with their interviews. I told one person — a really smart kid — ‘you need to cut your fingernails, because you want them focusing on you, not your fingernails.’”

Final Quad City Thoughts

There is a sense along the Coasts that the economy will basically be OK, even if government doesn’t function well. That’s not the case here. Many see their predicament as a direct result of government either functioning poorly or not all. Where there is a lot of talk along the coasts of resisting Trump at every step of the way, there seemed to be none of that talk among those we spoke to. The general consensus was: If there is something that can be done to help improve the local economy, whether it’s a Republican or a Democratic idea, it was a no-brainer — get it done.

“I’m willing to compromise just to see anything done,” a Galesburg woman told us. “Why even bother being labeled D or R? Just work together.” We heard some version of this from people who liked, loathed, or were seemingly indifferent to Trump.

Perhaps the most important thing we learned, however, is the power of listening — listening to listen, not to judge, not to respond, not to persuade. There is a lot of wisdom here, and we expect to find that in the many places we will visit.

This report was originally published on Medium.