Report Published July 14, 2025 · 15 minute read

The Pell Grant: What Do We Know About Degree Completion and Satisfactory Academic Progress?

Shinyoung Kim

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Iowa State University Department of Economics.

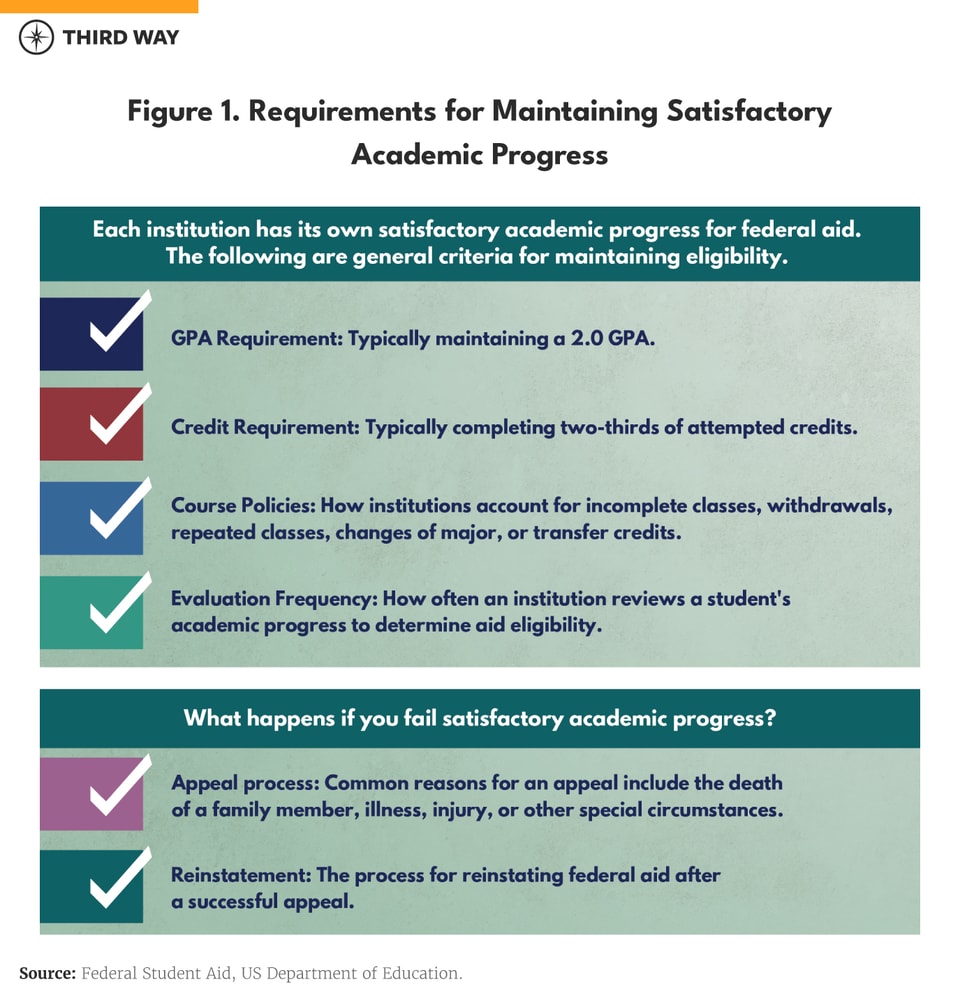

The Pell Grant program is the largest source of federal aid that helps low- to moderate-income students in the United States attend college. Despite the grant’s importance, we know little about its impact on degree completion. The Pell Grant program requires students to maintain satisfactory academic progress (SAP) to continue receiving the grant beyond their first year, which includes maintaining a minimum 2.0 GPA and completing at least two-thirds of their cumulative attempted credit hours. Additional SAP requirements can be set by institutions and have a direct relationship with a student's ability to complete college.

Research consistently demonstrates that the loss of Pell Grant funding—even temporarily—has a significant negative impact on college attendance and persistence, particularly for students with high financial need.1 This detrimental effect of losing grant aid on college completion is greatest for those who would benefit the most from the socioeconomic mobility of a college degree. This policy brief is based on research that found that up to 41% of Pell Grant recipients who lose their grants in their first year leave college as a result. If these students had retained their grants, four- and five-year graduation rates would rise by four and ten percentage points, respectively.

Research also shows that up to 33% of Pell recipients who lose their grant eligibility in the first year withdraw for reasons other than losing Pell Grant funding, such as family obligations. When assessing factors that contribute to degree completion, the focus often centers on direct financial expenses, such as tuition and living costs—which the Pell Grant helps cover or offset. Yet other critical factors—such as academic preparedness, family commitments, and guidance in navigating the college administrative system—are overlooked but important to understand.2

This policy brief advocates for a multifaceted approach to improving the effectiveness of the Pell Grant program by integrating academic and non-academic support services. To enhance student persistence and promote college completion, clearer communication of SAP requirements is needed to enhance student persistence and promote college completion. Financial aid should also be paired with broader support initiatives, such as childcare assistance, to address the diverse challenges faced by today’s students and ensure a stronger return on student and taxpayer investment.

Narrative

Since the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, the Pell Grant has served as a cornerstone of higher education access for low- to moderate-income students. Initial Pell eligibility is determined solely by financial need, as calculated by institutional financial aid offices using information from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). Students from families with incomes below an annually determined threshold qualify for the maximum Pell Grant award. Those above the threshold can receive adjusted amounts based on their family income.3 Unlike loans, Pell Grants do not require repayment, making them a key tool for improving college affordability.

Conventional wisdom may suggest that receiving a Pell Grant would positively impact degree completion. However, research suggests that Pell Grants have a limited impact on increasing degree attainment.4 Among Pell Grant recipients who enrolled in public four-year institutions in 2014, nearly half did not complete college within eight years, and only 39% earned a bachelor’s degree.5 This completion rate is substantially lower than the overall six-year completion rate of 64% for the 2014 cohort at four-year institutions.6

One reason that Pell Grants may not correlate with degree completion is due to the strings attached to the grant. Continued eligibility beyond the first year is contingent on meeting satisfactory academic progress (SAP) benchmarks meant to ensure students who receive Pell Grants are enrolled and making progress toward their degree. SAP requirements typically include maintaining a minimum grade point average (GPA) of 2.0 and completing at least two-thirds of attempted credits. Students who fail to meet SAP are given an additional term to improve their GPA, but repeated failure in two consecutive terms results in loss of grant eligibility for the next academic term. The SAP policy was introduced in response to a federal mandate to ensure “satisfactory progress” toward degree completion in the late 1970s.7

Although institutions have some flexibility in defining satisfactory progress, the policy must align with their graduation standards to ensure students stay on track. Students who fail to meet SAP for two consecutive terms may appeal to their institution's financial aid office, where staff determine whether the students have demonstrated extenuating circumstances. If the appeal is approved, students may regain their grant for the current or upcoming semester, depending on the financial aid office's decision. If denied, students lose their grant in the next academic term.

Although the link between receiving a Pell Grant and completing a credential isn’t as clear, the connection between losing Pell and decreased completion rates is evident. A failure to meet SAP standards significantly impacts student persistence and degree completion. In 2012, one-in-five (21%) first-year Pell Grant recipients were at risk of losing their grants after failing to meet GPA requirements.8

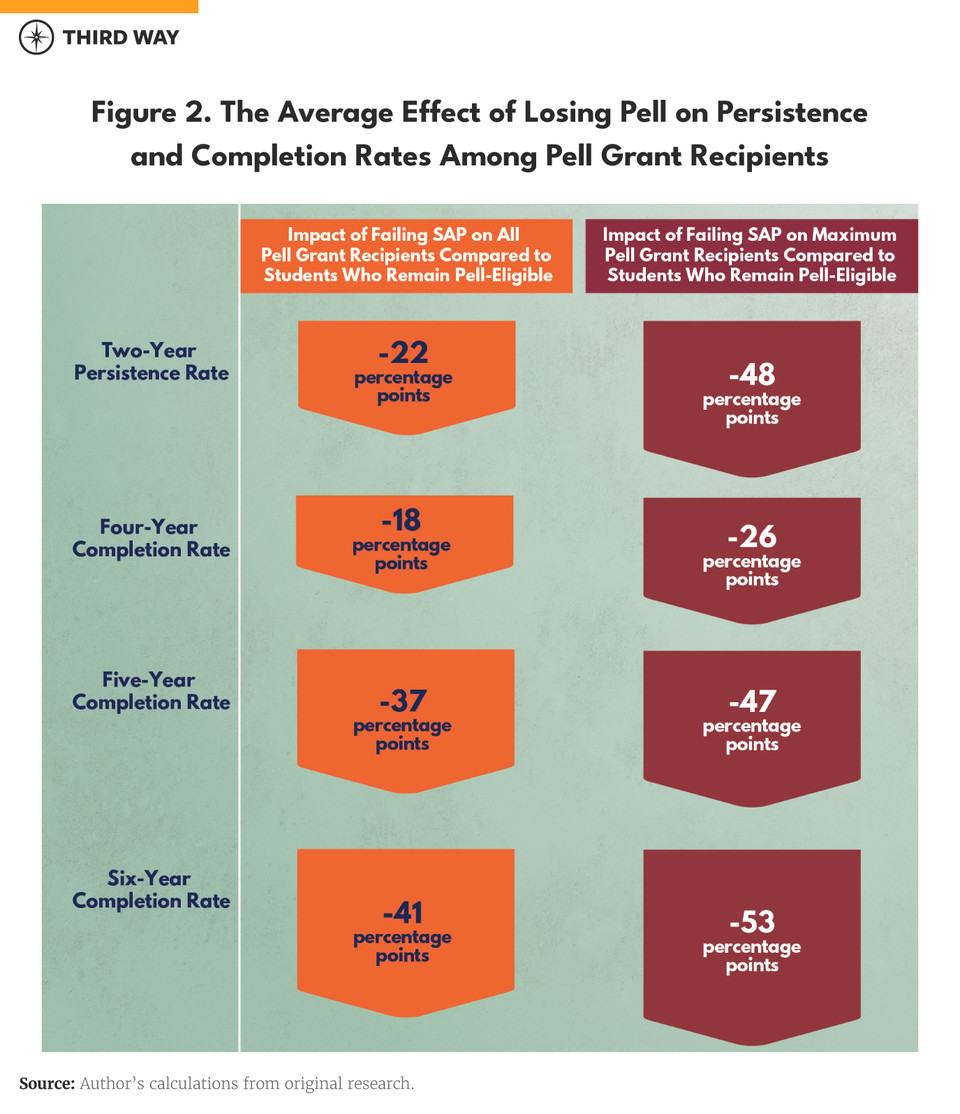

Students who lose eligibility after their first year are 22 percentage points less likely to enroll for a second year compared with those who remain Pell-eligible. This negative impact is larger among students with the greatest financial need—those eligible for the full grant are 26 percentage points less likely to persist. The consequences of SAP failure extend beyond persistence. Students who lose their grants are 18, 37, and 41 percentage points less likely to graduate within four, five, and six years, respectively, compared to those who remain eligible.

A key step in improving the efficiency of grant programs is to distinguish between two types of students: those who leave college due to grant loss and those who would withdraw regardless of receiving a grant. While some attrition is inevitable in any higher education system as students reassess their interests, time, and resources, students stopping out due to losing Pell Grant eligibility is antithetical to the purpose of the Pell Grant program. In order to maximize the ROI of student and taxpayer investment in the Pell Grants, policy solutions are needed to help more Pell-eligible students get across the finish line to a completed credential.

This research found that over four-in-ten (41%) Pell Grant recipients who lost aid withdrew from college as a direct result. This negative impact is particularly severe for full-aid recipients—students who receive the maximum award—with up to 45% leaving due to grant loss, compared to 34% of partial-aid recipients. In the optimal scenario where all 45% of full-aid and 34% of partial-aid recipients retained their grants—and if they were as likely to graduate as those who did graduate despite losing their grants in the first year—they would be approximately four percentage points more likely to graduate within four years compared to those receiving smaller awards, showing the significant positive impact of the Pell Grant in helping students finish college. Furthermore, full-aid recipients are estimated to be 10 percentage points more likely to graduate within five years if they retain their grants. Even in a more conservative scenario, where only 20% of full-aid recipients retained their grants, their likelihood of graduating within five years would still increase by up to seven percentage points.

For Pell-eligible students, receiving the grant is not the golden ticket that ensures college completion. Although it plays a key role in college access, additional student support is needed once a student arrives on campus. To inform policy decisions, this brief compares three groups of grant recipients: (1) students who complete their degree despite losing their grants, (2) students who do not graduate because of losing their grants—referred to hereafter as targeted students—and (3) students who do not graduate despite retaining their grants. Identifying targeted students helps uncover solutions that directly support their path to completion, while the third group highlights non-financial barriers that hinder student success.

Supporting Students to Completion

Institutions play a key role in helping students maintain SAP and complete their degrees. To best support students, institutions must clearly communicate SAP policies, ensuring that students understand the academic requirements, the consequences of not meeting them, and how this can impact their ability to complete their degree. Many students do not fully understand how SAP requirements work, with some even unaware of their existence. SAP policies can be confusing because institutions have flexibility in defining their requirements.9 For example, grading policies vary—while a standard grading scale assigns a letter grade of “C” to a 2.0 GPA, some institutions use a plus-minus grading system, leading to variability in determining GPA. Additionally, SAP evaluation methods differ; some institutions assess SAP after every term, while others only review GPA at the end of the spring term. These variations can create confusion, especially for students transferring between institutions with different SAP policies.10

The SAP appeal process can also be unclear, as financial aid offices determine whether appeals are approved, often without transparent criteria. Research shows that it is not clear how institutions make decisions about students' SAP appeals being approved or denied, and there is some concern that institutions may reject the appeals due to concerns about federal audits.11 Institutions rely on their financial aid administrator's judgment to determine whether a student's SAP appeal is approved. If a school denies a student’s appeal, the student is responsible for paying all educational costs out-of-pocket until they can raise their cumulative GPA to 2.0. Particularly for full-Pell recipients, the out-of-pocket cost can be the deciding factor between staying enrolled or leaving their higher education goals behind.

Financial challenges are the primary reason students leave college.12 Among 2019–20 Pell Grant recipients, 35% received the maximum award at the time of $6,195, which covered roughly 30% of tuition at four-year public institutions, along with housing and food.13 Nearly 80% of recipients came from families earning less than $40,000 per year, and those receiving the maximum award had an average family income of about $30,000 or less.14 Research consistently shows that even a relatively small reduction in aid significantly lowers degree completion rates. One study found that a $550 reduction in state funding led to fewer completed semester hours and a lower rate of degree completion.15 To prevent financial setbacks, institutions must take a proactive approach to communicate SAP policies and the appeal process clearly, ensuring that students with financial need fully understand the requirements and their implications for their aid packages.

Beyond financial aid policy, this research also found the need for a more efficient remedial course curriculum tailored to Pell Grant recipients. Targeted students were 30 percentage points more likely to be placed in remedial courses than those who graduated despite losing their grants, even though there were no observed differences in SAT math scores between the two groups. Existing studies raise concerns about the effectiveness of remedial courses, consistently showing that students placed in remedial courses have lower persistence rates than those placed directly into college-level courses, holding their SAT math scores constant.16 Research highlights that remedial coursework disproportionately hinders degree attainment for Pell Grant recipients.17 This is partly because Pell Grants typically do not cover the full cost of tuition, leaving students with additional financial burdens. Remedial courses do not count toward graduation requirements, extending the time needed to complete a degree, which can further discourage students from persisting in college and counts towards the total Pell lifetime eligibility used (LEU). Moreover, there are no nationwide policies governing remedial course placement, leading to inconsistencies in how students are assigned to these courses. The absence of standardized guidelines often results in misplacement—some students who do not require remediation are unnecessarily enrolled—adding time and cost to their degree program.18

There is also a need to implement more proactive nonacademic student-advising programs to address barriers beyond the classroom. Targeted students are 25 percentage points more likely to have a child in paid daycare while enrolled compared to those who lost their grants but graduated. Additionally, students who retained their grants but did not graduate were 40 percentage points more likely to have a child in paid daycare. Often, financial aid offices exclude childcare expenses when determining student aid awards. And data indicate that, even after accounting for grants and scholarships, student parents at public four-year institutions would need to work up to 90 hours per week on average to cover these costs.19 Existing research continues to highlight childcare as a significant barrier to college completion. However, many students remain unaware of available on-campus childcare assistance, resulting in a substantial portion of childcare subsidies going unclaimed. Strengthening outreach and awareness efforts could help ensure eligible students access these vital resources.

Policy Implications

The Pell Grant program must be accompanied by academic and nonacademic support services beyond simply increasing grant amounts while also implementing SAP policies in the best interests of students.20 This policy brief advocates for four key policy adjustments and on-campus initiatives, which would help more students maintain their Pell Grant awards, move towards college completion, and reap the financial benefits of a completed degree.

- Clarifying SAP Policies: Strengthening Institutional Communication and Transparency. Institutions must take proactive steps to clearly communicate SAP policies and provide transparent guidance on the appeal process. Students should understand the academic requirements needed to retain their financial aid and the steps to appeal in cases of unexpected circumstances. To better support students, institutions should clearly communicate their SAP policies and provide timely, proactive notifications to those at risk of losing their grants. These notifications should include transparent information about the appeal process, explicitly defining what qualifies as a “special circumstance.” For example, rather than a single notification at the end of the semester, students could receive multiple updates on their SAP status throughout the term. The earlier and more frequently students are informed of the risk of losing their grants, the better they can take action to maintain eligibility—shifting SAP policies from being merely restrictive to actively supportive. Lastly, student advising should not be limited to financial aid offices alone—faculty members should also be informed about SAP policies and encouraged to proactively communicate with students about financial aid requirements.21

- Rethinking SAP Appeals Processes: Clarifying Policies For Student Pell Grant Reinstatement. Students who fail SAP and lose access to Pell Grant (and other forms of Title IV funding) must appeal to their institution for reinstatement. If approved, a school can place a student on financial aid probation or an academic plan to get back in good standing. While federal policy sets baseline SAP standards, institutions have wide latitude and discretion in determining whether a student can regain aid.22 Many institutions take an overly cautious approach in reinstatement due to concerns around compliance, yet such policies and decisions have a detrimental effect on a student accessing Pell Grant dollars again. Institutions should work to increase clarity around reinstatement policies that uphold federal regulations while providing pathways to reinstatement that allow students to continue making progress towards their degree.

- Clarifying Remediation: Strengthening State Guidance on Course Placement. State governments and institutions must recognize the negative consequences of unnecessary enrollment in remedial courses and provide clearer guidance on placement to improve program efficiency. For Pell Grant recipients, remedial coursework can pose a barrier to college completion. State governments could establish clearer guidelines for student placement to ensure that remedial courses primarily serve those in academic need, preventing unnecessary over-enrollment. Institutions may also consider redesigning remedial coursework. Initiatives such as Summer Bridge programs allow students to complete remedial courses before their first year, potentially reducing delays in degree progression. Although evidence on the long-term impact of these programs on degree attainment is limited, restructuring remedial education to minimize both time and financial burdens appears to be a promising strategy for supporting student success.

- Beyond Academics: Strengthening Targeted Non-academic Student Advising. Institutions must adopt a more proactive and tailored approach to student advising, ensuring that grant recipients receive comprehensive support beyond academics, including guidance on accessing campus resources such as childcare assistance. In 2019, approximately 27% of Pell Grant recipients reported having dependents other than a spouse, with 54% experiencing food insecurity and 62% facing housing insecurity.23 Yet, many eligible student parents are unaware of their eligibility for childcare aid programs.24 Student parents frequently experience fluctuations in earnings from part-time jobs, yet no support services exist to help them during periods of income loss, making them highly vulnerable to financial instability. Despite these resource limitations, childcare support programs have demonstrated success in promoting student persistence.

Methodology

This brief utilizes data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students (BPS) survey (BPS:12/17) from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). This research first identifies students who leave college due to grant loss, distinguishing them from those who would withdraw regardless. It then compares these students just below and just above the income threshold for maximum Pell Grant eligibility to estimate the program’s impact on student outcomes. The results are based on regression discontinuity methods, and I provide nonparametric bounds on the local average treatment effects.

More detailed methodological information can be found here.