Report Published May 23, 2019 · 32 minute read

Cyber Enforcement in Four Key States

Brandon Gaskew

In the range of national security challenges facing US presidential administrations, only a few involve a foreign adversary causing harm to an American without ever leaving their country—it's cyber. According to a Pew Survey on global threats, Americans rank foreign cyberattacks as their top threat, ahead of even terrorism.1 And it’s no wonder. America is facing a cybercrime wave and it is getting bigger every year–undermining America’s national security and affecting every sector of the economy. In the aggregate, cybercrime costs the US economy up to $109 billion and trillions globally.2 From cyber vulnerabilities of America’s military weapons, to the theft of America’s intellectual property, to election interference, to the ransomware used to cripple US cities, to the financial crimes and identity thefts that affect average Americans, the range of cybercrime and cybercriminals is vast.3

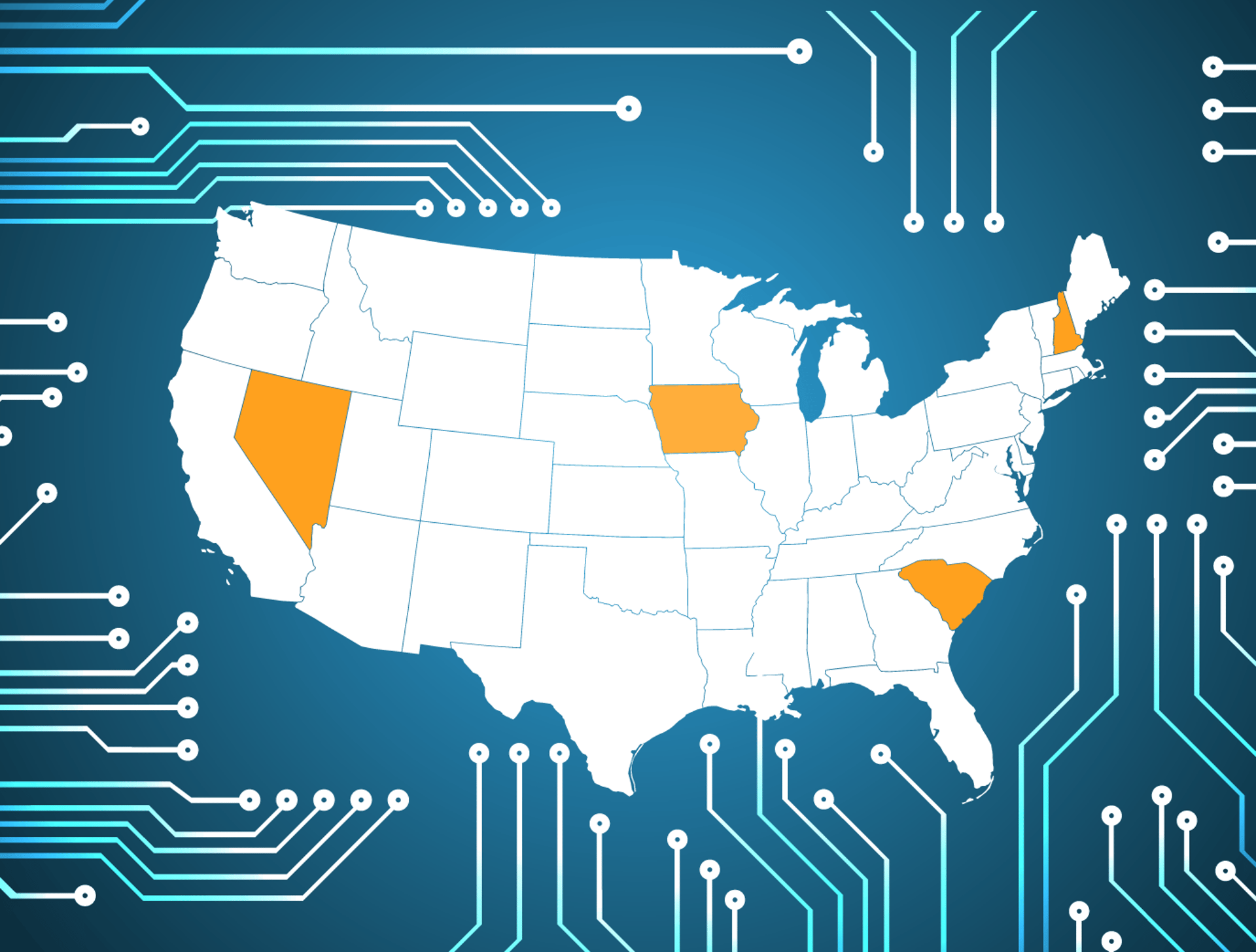

The 2020 presidential election offers an opportunity for Americans to raise concerns about cybercrime and draw attention to cybersecurity at a state and local level. To help inform these discussions, Third Way has prepared this memo to educate candidates about the growing national security threat of cybercrime, and the resources that have been created in four key states to tackle the threat: Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina. 2020 presidential candidates should use the information in this memo to elevate the conversation on cybercrime and develop a national cyber strategy to protect the American people.

This memo contains two components:

- First, it provides a brief overview of the cybercrime threat to the United States and what law enforcement can do to combat it. According to US government data, the most vulnerable victim population is those over age 60.4 While the states with the largest victim populations are California, Florida, and Texas, there is no state or jurisdiction, without a victim of a cybercrime.5 Sadly, the vast majority of cybercrimes go unprosecuted. According to Third Way’s assessment of the US federal government’s own data, only 3 in 1,000 cybercrimes ever see an arrest.6 Worse, only 1 in 6 cybercrimes are reported, meaning that the chances that a cybercriminal gets caught are miniscule.7 America can and should do better.

- Second, it showcases how cybercrime has impacted victims in four key states—Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina—and the resources those states have established to reduce cybercrime and boost cybersecurity. We analyze who the victims are and what institutions in those states are fighting this growing cybercrime wave to guide the cyber discussion as attention draws to those states.

Third Way’s broader report “To Catch a Hacker”8 contains further recommendations for policy areas that current and future US presidents must focus on to making progress in reducing cybercrime.9

Cybercrime in the United States

The United States is facing a cybercrime wave that continues to cause increasing costs to America’s national and economic security.

In 2017, over 300,000 cybercrime incidents were reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) — which is likely a vast undercount since many victims do not report their victimization.10 The ubiquity of technology means every critical infrastructure sector in the United States—from nuclear power plants to water facilities— utilizes some form of computer-enabled system for their operations that, if attacked successfully, could have devastating impacts on Americans. That is why the US Department of Treasury has designated cyber incidents as one of the biggest threats to the stability of the entire US financial system.11

Despite the scope and size of the cybercrime threat, Third Way uncovered a stunning cyber enforcement gap, allowing cybercriminals to operate with near impunity. Only 3 out of 1,000 malicious cyber incidents in the United States annually see an arrest, which is an enforcement rate of less than 1%.12 By comparison, the clearance rate for property crime was approximately 18% and for violent crimes 46%, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report for 2016.13

Government is the only institution with the authority to pursue human cybercriminals and bring them to justice. However, in the United States, a heavy focus of cyber policy discussions has been building better cyber defenses against intrusion. There is no discussion as to how the government can also impose consequences on cybercriminals that continue to attack Americans and our institutions in every state. To close the cyber enforcement gap, the United States needs a comprehensive strategy for strengthening the US government’s abilities to identify, stop, and punish cybercriminals and other malicious cyber actors, which the country does not currently have.

The 2020 US presidential election offers an opportunity for Americans to raise concerns about cybercrime and hear from candidates on all sides about their views. Fortunately, states across the country are directing cyber resources to protect their residents, local businesses, government institutions, organizations, and critical infrastructure from cybercrime and help to support investigations. State and local law enforcement agencies are creating specialized cybercrime units, cyber fusion centers are being setup to share cyber threat intelligence, and public-private partnerships are creating cyber incident response plans.

As attention draws to Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina, this is an opportunity to showcase how cybercrime has impacted residents in those states and the work that is happening to protect against and combat the threat at a state and local level. In order to take decisive action to address the national and economic security impacts of malicious cyber activity on Americans, it helps to look through a state and local lens.

Cyber Resources: Iowa

Overview of Iowa’s Cyber Response

In 201614 and 2017,15over 1,500 Iowans reported internet crime complaints to the FBI. In 2017, Iowans reported a financial loss of over $4 million16 to cybercrime.17

Iowa began to fortify its cyber resources starting in 2012. Then, former Governor Terry Branstad hired Iowa’s first Chief Information Officer (CIO) to manage and coordinate the cyber resources of the state government.18 In 2015, former Governor Branstad directed the CIO to partner with the Iowa National Guard, Iowa Homeland Security and Emergency Management Department, Iowa Communications Network, the Department of Public Safety, and other key partners to respond to cyber incidents in the state.19

As many states mobilize their cyber resources, here are three unique measures Iowa developed to improve its response to cyberattacks:

- Created cyber education programs: Iowa State University in partnership with the Iowa National Guard and the state’s Office of the Chief Information Officer established the Iowa Cyber Alliance, the nation’s first cybersecurity program dedicated to education, outreach, and training of government agencies, businesses, and all its citizens on cyber threats protection.20

- Instituted public-private cyber partnerships: Organizations like the Safeguard Iowa Partnership, a coalition of business and government leaders, work to facilitate assessments that have been used to identify and prioritize statewide cybersecurity projects21 and provide extensive cybersecurity awareness resources to the public.22

- Established a cyber-quarterback to coordinate and manage resources. Iowa created an Office of the Chief Information Officer as an independent agency to lead and coordinate Iowa’s cyber resources, giving it authority to establish information technology (IT) standards used by state agencies, direct agency IT staff, and recommend approval of IT employment decisions with the Iowa Department of Management.23

Recent Iowa Cyberattacks

The Office of the Iowa Attorney General maintains an online database24 of company data breaches from 2011 onwards.25 Here are recent examples of the impact cyberattacks can have on local municipalities and businesses:

Local Government

- On October 22, 2018, Muscatine County computer networks were hit by the same ransomware that hit the city of Muscatine a few days prior. It prevented police officers from accessing their mobile computers in their squad cars, and the county jail lost access to files linking the National Crime Information Center database.26

- On October 18, 2018, the city of Muscatine was hit by a cyberattack.27 Muscatine government servers were hit with ransomware28 that paralyzed city services. Tasks as simple as paying for parking tickets or checking books out of the public library were unavailable.29

Medical

- In August 2018, Iowa-based Jones Eye Clinic was hit by a ransomware attack that compromised as many as 40,000 patients’ information.30 Information as sensitive as patients’ medical record numbers, addresses, and general description of clinic visits was potentially stolen.

- On July 30, 2018, UnityPoint, one of Iowa’s main hospitals was hit by a cyberattack that impacted nearly 1.4 million patients.31 The hackers used a phishing email to access UnityPoint’s network, potentially giving the hackers access to patients’ medical information.

Education

- In October 2017, the Johnston school district was targeted by a hacker group, resulting in student names, addresses, and telephone numbers being posted online.32

Recommended Cyber Resources to Visit

Third Way has identified three vital stops in Iowa that showcase how malicious cyber activity has impacted Iowa and two measures Iowa is taking to protect residents and critical infrastructure from the cyber threat:

- The Iowa Cyber Alliance is an organization led by Iowa State University and housed in its Information Assurance Center. It is the nation’s first program dedicated to providing cybersecurity education, outreach, and training to government agencies, businesses, and all Iowans.33

- Iowa’s Air National Guard has been mobilized as an important state cyber resource through the Iowa Air National Guard Cyber Protection Team (CPT) to assist the government of Iowa and private sector critical infrastructure in responding to cyber incidents.34 The CPT is officially the 168th Cyberspace Operations Squadron within the 132nd Wing.35

- Muscatine, IA, with a population of roughly 24,000, was the target of a cyberattack in October 2018. City servers were infected with ransomware, grinding city services to a halt. Tasks as simple as paying for parking tickets or checking books out of the public library were unavailable to residents.36

Key Iowa State and Federal Government Cyber Entities

Local, state, and federal government agencies have a vital role in protecting residents from cyberattack and bringing cybercriminals that attack Americans to justice. Third Way has compiled a list of these entities:

State Cyber Entities

- Office of the Chief Information Officer (CIO): The CIO has centralized authority over Iowa state agencies’ information technology (IT). It approves IT standards for state agencies and can recommend and review approval of IT professionals at those state agencies.37

- Iowa Information Security Division (ISD): ISD is led by the Iowa CIO and has responsibility to respond to major cyberattacks and partners with federal, state, and non-profit cybersecurity organizations, including the US Department of Homeland Security and Iowa Homeland Security and Emergency Management.38

- Iowa Department of Public Safety (DPS): DPS serves as Iowa’s state law enforcement agency. The Division of Criminal Investigation houses the Cybercrime Unit, which is responsible for conducting cybercrime investigations.39

- Iowa Communications Network (ICN): ICN is an independent state agency that administers Iowa’s statewide fiber optic telecommunications network. ICN provides firewall service to protect against unauthorized network access, incident response, network security testing, and protection against cyberattacks.40

- Iowa Homeland Security and Emergency Management Department (HSEMD): HSEMD’s mission is to lead and coordinate Iowa’s response to homeland security and emergency incidents.41

- Iowa Attorney General (AG): The Iowa AG is the chief legal officer of the state. Under Iowa law, any security breach that affects at least 500 Iowa residents’ companies must provide written notice to the AG’s Consumer Protection Division Director within five business days. The AG also maintains a database online of security breaches from 2011 onwards.42

- Iowa National Guard: The Iowa Air National Guard Cyber Protection Team assists the government of Iowa and private sector critical infrastructure in responding to cyber incidents.43

Federal Entities

There are not many federal law enforcement agencies with field offices in Iowa. The only notable entities are a Secret Service field Office located in Des Moines, IA and two US Attorney’s Offices:

- US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Iowa: The US Attorney’s Office is headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa’s largest city. The Office has a Criminal Division responsible for prosecuting any cybercrimes that occur within the district.44

- US Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Iowa: The US Attorney’s Office is headquartered in Cedar Rapids, Iowa’s second largest city. The Office has a Criminal Division responsible for prosecuting any cybercrimes that occur within the district.45

University Cyber Centers

To effectively address cyberattacks, local, state, and federal entities need trained cyber professionals. There are 299,000 unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States and the gap is expected to reach 1.8 million by 2022, according to a 2018 report authored jointly by the Department of Commerce and DHS.46 The gap in unfilled cybersecurity positions covers both the private and public sectors and vacancies range from IT specialists to law enforcement cyber investigators. The large vacancy in positions affects the government and companies’ ability to improve their cybersecurity and law enforcement’s ability to go after cybercriminals.47 Universities are taking a lead in addressing this cyber workforce shortage and are creating cyber centers to provide education and training resources for the next generation of cyber professionals.

Here is a list of Iowa universities that have created cyber centers:

- Eastern Iowa Community College (EICC) Cyber Center: EICC established their Cyber Center to meet regional demands for cybersecurity education and training.48

- Iowa Cyber Hub: Iowa State University and Des Moines Area Community College (DMACC) formed the Iowa Cyber Hub in partnership. It is designed to be the focal point for cybersecurity education, outreach, training, and to foster additional interaction between companies and partner schools through internships, training opportunities, and focused projects.49

- Iowa State University Information Assurance Center (IAC): The IAC is a multidisciplinary center with a mission to conduct comprehensive cybersecurity research, training and education, cybersecurity employment pathways, security literacy and outreach for all Iowans, and partnerships with government and industry.50

Military Installations in Iowa

States are using their National Guard units to combat the growing national security threat of cyberattacks. National Guard units are being organized into cyber mission teams. Some are tasked with protecting state-level interests, and others are under the direction of US Cyber Command and are charged with protecting Department of Defense networks and national critical infrastructure.51 There are currently 3,880 National Guardsmen assigned to cyber service, spread across 59 cyber units in 38 states.52

Here are all the major military installations in Iowa:

- Camp Dodge, Johnston, IA (Headquarters of the Iowa National Guard)

- Fort Des Moines, Des Moines, IA

- Iowa Army Plant, Des Moines County, IA

Cyber Resources: New Hampshire

Overview of New Hampshire’s Cyber Response

In 2016 and 2017, over 1,100 New Hampshirites reported internet crime complaints to the FBI.53 The financial impact of cyberattacks on New Hampshire is increasing every year. In 2016, New Hampshirites reported to the FBI a financial loss of $3.1 million,54 and in 2017 over $3.7 million55 due to cybercrime.56

In 2016 New Hampshire created the New Hampshire Cyber Integration Center (NHCIC) to serve as the statewide focal point for cybersecurity monitoring, information sharing, and threat analysis.57

As many states mobilize their cyber resources, here are two unique measures New Hampshire developed to improve its ability to respond to cyberattacks:

- Created a cybersecurity alert system: The State of New Hampshire operates a cybersecurity alert level on their website that is updated daily with threat information from the New Hampshire Information and Analysis Center.58 This is invaluable information that citizens, businesses, and local governments can use to assess the cyber threat level daily.

- Established a state cyber department to coordinate and manage resources: New Hampshire has unified all its cyber resources into one organization. The Department of Information Technology is led by a Commissioner and has legal authority to manage and coordinate all technology resources for the state government.59

Examples of Recent New Hampshire Cyberattacks

Cyberattacks have hit every sector of the US economy. Here are recent examples of the impact cyberattacks have had on local municipalities and businesses in New Hampshire:

Government

- In April 2018, an energy utility company that supplies power to Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire was hit by a cyberattack. It fortunately did not compromise any customers data or disrupt service; however, it did affect the energy company’s ability to process some transactions.60 The damage in this cyberattack was minimal, but if an attack disrupted power across New England, the consequences would be grave for those residents.

- In March 2018, Portsmouth, New Hampshire’s city computer system was infected with malware. The cyberattack caused emails to be sent purporting to be city officials, asking recipients to pay a city invoice and instructing them to open a link for further details.61

Business

- In 2016, Dyn, based in Manchester, New Hampshire, which provides services to websites like Twitter, Netflix, and Visa, was hit by a cyberattack disrupting internet service across the East Coast.62

Education

- In April 2015, the Concord School District was hit by a cyberattack, compromising the W-2 forms of everyone who received payment from the school in 2015. Some of the stolen information was used to file fraudulent tax returns.63

Recommended Cyber Resources to Visit

Third Way has identified three vital stops in New Hampshire. One stop was the victim of a cyberattack and showcases how malicious cyber activity has impacted New Hampshire. The other two stops are measures New Hampshire is taking is taking to protect residents and critical infrastructure from the cyber threat:

- New Hampshire Cyber Integration Center (NHCIC): The NHCIC serves as New Hampshire’s focal point for coordinating cybersecurity monitoring, information sharing, and threat analysis.64

- New Hampshire Department of Safety: The Major Crimes Unit within the Investigative Services Bureau has computer crime investigators that handle many of the New Hampshire’s cybercrime investigations.65

- University of New Hampshire Cybersecurity Center of Excellence: The Cyber Center partners with academia, industry, and government. Its mission is to educate cybersecurity professionals on technical and societal challenges in cybersecurity.66

Key New Hampshire State and Federal Government Cyber Entities

Local, state, and federal government agencies have a vital role in protecting residents from cyberattacks and bringing cybercriminals that attack Americans to justice. Third Way has compiled a list of these entities:

State Cyber Entities

- New Hampshire Cyber Integration Center (NHCIC): The NHCIC serves as New Hampshire’s focal point for coordinating cybersecurity monitoring, information sharing, and threat analysis.67

- New Hampshire Information and Analysis Center (NHIAC): The NHIAC serves as New Hampshire’s all-crimes/all-hazards information and analysis center. It can monitor open and classified sources, including those related to cyber threats, and then share information with the public and private sector.68

- New Hampshire Department of Safety: The Department of Safety operates the cybersecurity alert level to allow the public to monitor daily levels of malicious cyber activity.69 It also houses the state’s homeland security and emergency operations, which have the responsibility of responding to major disasters.70

- New Hampshire Department of Information Technology: The Department of Information Technology serves as a unified government entity for all of New Hampshire’s cyber resources. The Department of Information Technology is led by a Commissioner and has legal authority to manage and coordinate all technology resources for the state government.71

- New Hampshire Department of Safety: The Department of Safety contains the Major Crimes Unit within the Investigative Services Bureau, which has computer crime investigators that handle many of New Hampshire’s cybercrime investigations.72

Federal Cyber Entities

There are not many federal law enforcement agencies with field offices in New Hampshire. The only notable entity is a US Attorney’s Office located in Concord, New Hampshire:

- US Attorney’s Office for the District of Hampshire: The US Attorney’s Office serves as the state’s chief federal law enforcement officer and prosecutes cybercrimes within New Hampshire.73

University Cyber Centers

To effectively address cyberattacks, local, state, and federal entities need trained cyber professionals. There are 299,000 unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States and the gap is expected to reach 1.8 million by 2022, according to a 2018 report authored jointly by the Department of Commerce and DHS.74 The gap in unfilled cybersecurity positions covers both the private and public sectors, and vacancies range from IT specialists to law enforcement cyber investigators. The large vacancy in positions affects the government and companies’ abilities to improve their cybersecurity and law enforcement’s ability to go after cybercriminals.75 Universities are taking a lead in addressing this cyber workforce shortage and are creating cyber centers to provide education and training resources for the next generation of cyber professionals.

Here is a list of New Hampshire universities that have created cyber centers:

- Dartmouth College, Institute for Security Technology, and Society: Has been designated a Center of Academic Excellence in Information Research by the National Security Agency and DHS. Its mission is to research and advance information security and privacy.76

- University of New Hampshire Cybersecurity Center of Excellence: The Cyber Center partners with academia, industry, and government. Its mission is to educate cybersecurity professionals on technical and societal challenges in cybersecurity.77

Military Installations in New Hampshire

States are using their National Guard units to combat the growing national security threat of cyberattacks. National Guard units are being organized into cyber mission teams. Some are tasked with protecting state-level interests, and others are under the direction of US Cyber Command and are charged with protecting Department of Defense networks and national critical infrastructure.78 There are currently 3,880 National Guardsmen assigned to cyber service, spread across 59 cyber units in 38 states.79

Here are all the major military installations in New Hampshire:

- Portsmouth Shipyard, Portsmouth, NH

- Pease Air National Guard, Portsmouth, NH

- United States Coast Guard Station Portsmouth Harbor, New Castle, NH

- United States Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, Hanover, NH

- Army National Guard, Nashua, NH

- Army National Guard, Rochester, NH

Cyber Resources: South Carolina

Overview of South Carolina’s Cyber Response

In 2016 and 2017, over 3,500 South Carolinians reported internet crime complaints to the FBI.80 The financial impact of cyberattacks on South Carolina continues to increase. In 2016, South Carolinians reported a loss close to $11 million81 and in 2017 over $13 million82 to the FBI due to cybercrime.83

In response to the growing cyber threat, South Carolina General Assembly created the Division of Information Security in 2013, giving it responsibility for statewide polices, standards, and coordination of cybersecurity resources.84

As many states mobilize their cyber resources, here are three unique measures South Carolina has developed to improve its ability to respond to cyberattacks:

- Created cyber education programs: The University of South Carolina and the South Carolina Department of Commerce founded SC Cyber in 2016.85 SC Cyber partners with academia, industry, and government to create and offer programs related to cyber training, workforce development, education, advanced technology development, and critical infrastructure protection.86

- Modernized cybersecurity legislation: South Carolina passed new cybersecurity laws for insurance companies licensed in the state effective January 1, 2019.87 The rules require licensed insurance companies to notify state insurance authorities of data breaches within 72 hours after confirming that nonpublic data within the insurance company’s system was accessed.88

- Instituted a centralized management system for cyber: South Carolina has organized the states’ information technology into a Division of Information Security led by a Chief Information Security Officer.89 It is important for states to have a centralized manager who can mobilize and coordinate resources during a cyber incident.

Examples of Recent South Carolina Cyberattacks

Cyberattacks have hit every sector of the US economy. Here are recent examples of the impact cyberattacks have had on local municipalities and businesses in South Carolina:

Government

- In January 2018, the Spartanburg County Public Libraries were the target of a ransomware attack, an attack that prevents users from accessing their computer system until a payment is made. The county has a population close to 300,000.90 The cybercriminals blocked access to the computer system unless $36,000 in bitcoin was paid. The attack halted all access to the Libraries online catalog and website.91

- In December 2018, the Mount Pleasant Police Department’s computer system was infected with ransomware. The department was able to remove the infected computers from the networks before the cyberattack caused more severe damage.92

Medical

- In November 2018, employees at Roper St. Francis were hit with a phishing attack, allowing a malicious actor to gain access to their email accounts. The cybercriminal was able to gain access to some patient information such as medical record numbers, health insurance information, and some Social Security numbers.93

Education

- In January 2019, hackers infiltrated the computer network of Greenwood School District 5 and stole $1,200 by accessing the payroll system.94

Recommended Cyber Resources to Visit

Third Way has identified three vital stops in South Carolina. One stop was the victim of a cyberattack and showcases how malicious cyber activity has impacted South Carolina. The other two stops are measures South Carolina is taking to protect residents and critical infrastructure from the cyber threat:

- SC Cyber: is based at the University of South Carolina, SC Cyber is a consortium of partners across academia, industry, and government. The mission of this entity is to provide cyber training, education, workforce development, advanced technology development, and critical infrastructure protection.95

- Spartanburg County Public Libraries: in January 2018, the Spartanburg County Public Libraries were the target of a ransomware attack. The cybercriminals blocked access to the computer system unless $36,000 in bitcoin was paid. The attack halted all access to the Libraries online catalog and website.96

- South Carolina National Guard: works to protect the state against cyberattacks through the 125th Cyber Protection Battalion, which was established in 2017 by South Carolina as the first unit assigned to protect the state against cyberattacks.9798

Key South Carolina State and Federal Government Cyber Entities

Local, state, and federal government agencies have a vital role in protecting residents from cyberattacks and bringing to justice cybercriminals that attack Americans. Third Way has compiled a list of government entities:

State Cyber Entities

- South Carolina, Law Enforcement Division (SLED): The SLED is the statewide law enforcement agency.

- The Computer Crime Center works to investigative cybercrimes in the state.99

- The Homeland Security division responds to any emergency incident in the state including those that are cyber-related.100

- SC Cyber: SC Cyber is based at the University of South Carolina and is a consortium of partners across academia, industry, and government. The mission is to provide cyber training, education, workforce development, advanced technology development, and critical infrastructure protection.101

- Division of Information Security: The Division of Information Security is led by the South Carolina Chief Information Officer and is responsible for setting statewide cyber polices standards, programs, and services. 102

- South Carolina InfraGard: InfraGard is an information sharing partnership between the FBI and the private sector in South Carolina designed to protect critical infrastructure.103

- South Carolina National Guard: The South Carolina National Guard established the 125th Cyber Protection Battalion, the first unit assigned to protect the state against cyberattacks.104

Federal Cyber Entities

- Federal Bureau of Investigation: The FBI maintains a field office in Columba, SC.105

- US Attorney’s Office for the District of South Carolina: The US Attorney’s Office is the chief federal law enforcement officer in the state and has offices in Columbia, Greenville, Florence, and Charleston. Through the Criminal Division, the Office prosecutes cybercrimes within the state of South Carolina.106

- United States Secret Service (USSS): The USSS operates a South Carolina Electronic Crimes Task Force designed to prevent, detect, and investigate cyberattacks on financial institutions and critical infrastructures.107

University Cyber Centers

To effectively address cyberattacks, local, state, and federal entities need trained cyber professionals. There are 299,000 unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States and the gap is expected to reach 1.8 million by 2022, according to a 2018 report authored jointly by the Department of Commerce and DHS.108 The gap in unfilled cybersecurity positions covers both the private and public sectors and vacancies range from IT specialists to law enforcement cyber investigators. The large vacancy in positions affects the government and companies’ ability to improve their cybersecurity and law enforcement’s ability to go after cybercriminals.109 Universities are taking a lead in addressing this cyber workforce shortage and are creating cyber centers to provide education and training resources for the next generation of cyber professionals.

Here is a list of South Carolina universities that have created cyber centers:

- Clemson University Cybersecurity Center: The Cybersecurity Center engages in cybersecurity research, education, industry partnership, and community engagement.110

- SC Cyber: SC Cyber is based at the University of South Carolina and is a consortium of partners across academia, industry, and government. The mission is to provide cyber training, education, workforce development, advanced technology development, and critical infrastructure protection.111

- South Carolina State University Center for Excellence in Cyber Security: The Center for Excellence is designed to serve as a focal point on cyber education, training, and awareness.112

- Trident Technical College Cyber Center: The Cyber Center is the recipient of an Office of Naval Research grant until 2020, and its goal is to promote higher education and research in cyber defense and training professionals with cyber defense expertise.113

Military Installations in South Carolina

States are using their National Guard units to combat the growing national security threat of cyberattacks. National Guard units are being organized into cyber mission teams. Some are tasked with protecting state-level interests, and others are under the direction of US Cyber Command and are charged with protecting Department of Defense networks and national critical infrastructure.114 There are currently 3,880 National Guardsmen assigned to cyber service, spread across 59 cyber units in 38 states.115

Here are all the major military installations in South Carolina:

- Fort Jackson, Columbia, SC

- Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, Beaufort, SC

- Marine Crops Recruit Depot Parris Island, Port Royal, SC

- Naval Hospital Beaufort, Beaufort, SC

- Naval Hospital Charleston, Charleston, SC

- Naval Weapons Station Charleston, Goose Creek, SC

Cyber Resources: Nevada

Overview of Nevada’s Cyber Response

In 2016, Nevadans filed over 3,700116 internet crime complaints to the FBI, and the figure ballooned to over 4,600 in 2017.117 The economic impact of these crimes has continued to increase. In 2016 Nevadans reported a financial loss of over $15 million,118 which increased in 2017 to over $19 million.119

In response to the growing cyber threat, Nevada passed legislation to establish the Nevada Office of Cyber Defense Coordination (OCDC) in 2017. It was designed to integrate state cyber resources and oversee implementation of Nevada’s cybersecurity strategy. It is responsible for policy, planning, and coordination in the event of a cyber incident.120

As many states mobilize their cyber resources, here are three unique measures Nevada developed to improve its ability to respond to cyberattacks:

- Established grants to train cyber professionals: Nevada views cybersecurity professionals as vital to its economy. The Nevada Governor’s Office of Science, Innovation, and Technology has awarded over $600,000 in grants to organizations create cyber workforce programs.121 Nevada has as many as 1,6333 unfilled cybersecurity job openings.122

- Formed private and public sector cyber incident response organizations: Southern Nevada Cybersecurity Alliance is a volunteer service of cybersecurity professionals, who responded to cyber incidents threatening the critical infrastructure of Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, and Henderson.123

- Started cyber initiatives to empower students and women: In February 2019, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak announced that Nevada is partnering with other organizations to launch Girls Go Cyberstart and Cyber FastTrack. These two initiatives to help young women in high school and college with opportunities to gain cybersecurity skills and help with professional development.124

Examples of Recent Nevada Cyberattacks

Cyberattacks have hit every sector of the US economy. Here are recent examples of the impact cyberattacks have had on local municipalities and businesses in Nevada:

Government

- In 2016, the Nevada Department of Transportation was hit by a cyberattack, compromising the Personal Indefinable Information of state employees, such as dates of birth and Social Security numbers.125

Business

- In 2016, a cyberattack against the Nevada State Medical Marijuana Program led to the records of medical marijuana card holders being leaked.126

- In 2016, the Hard Rock Las Vegas suffered its second data breach, with malware targeting the credit card information of customers.127

- In 2014, the Las Vegas Sands casino was the victim of an Iranian cyberattack, which crippled thousands of servers by wiping them with malware.128

- In 2014, the Venetian and Palazzo casinos websites were hacked. The casino websites were taken down and employee personal information was stolen, costing almost $40 million in damage.129

Recommended Cyber Resources to Visit

Third Way has identified three vital state resources that showcase measures Nevada is taking to protect residents and critical infrastructure from the national security threat of cyberattacks:

- University of Nevada, Reno, Cybersecurity Center: The Cybersecurity Center focuses on educational and research opportunities in cybersecurity and seeks to enhance Nevada’s cybersecurity readiness.130

- The Nevada Office of Cyber Defense Coordination (OCDC): OCDC serves as Nevada’s centralized hub for cybersecurity strategy, planning, and coordination.131

- Southern Nevada Cybersecurity Alliance (SNCA): SNCA is a volunteer service of cybersecurity professionals committed to defending the critical infrastructure of Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, and Henderson Nevada from cyberattacks.132

Key Nevada State and Federal Government Cyber Entities

Local, state, and federal government agencies have a vital role in protecting residents from cyberattacks and they have the authority to go after cybercriminals. Third Way has compiled a list of these agencies:

State Cyber Entities

- The Nevada Office of Cyber Defense Coordination (OCDC): OCDC serves as Nevada’s centralized hub for cybersecurity strategy, planning, and coordination.133

- Department of Emergency Management, Homeland Security Section (DEM): The Homeland Security Section mobilizes state resources to respond to acts of terrorism and related emergency, including cyber incidents.134

- Department of Business and Industry, Nevada Consumer Affairs: The Office of Consumer Affairs works to protect residents from unfair and deceptive business practices, including online scams.135

- Attorney General: The Attorney General operates a Technological Crime Advisory Board, consisting of state, local, and federal officers, designed to facilitate cooperation in the detection, investigation, and prosecution of technological crimes.136

Federal Cyber Entities

- US Attorney’s Office for the District of Nevada: The US Attorney’s Office comprises the entire state of Nevada. Through its Criminal Division, it can prosecute any cybercrime in the state.137

- Federal Bureau of Investigation: The FBI maintains a field office in Las Vegas.138

- Homeland Security Investigations (HSI): HSI operates a field office in Las Vegas.139

- United States Secret Service (USSS): USSS operates a field office in Reno and Las Vegas.140

University Cyber Centers

To effectively address cyberattacks, local, state, and federal entities need trained cyber professionals. There are 299,000 unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States and the gap is expected to reach 1.8 million by 2022, according to a 2018 report authored jointly by the Department of Commerce and DHS.141 The gap in unfilled cybersecurity positions covers both the private and public sectors and vacancies range from IT specialists to law enforcement cyber investigators. The large vacancy in positions affects the government and companies’ ability to improve their cybersecurity and law enforcement’s ability to go after cybercriminals.142 Universities are taking a lead in addressing this cyber workforce shortage and are creating cyber centers to provide education and training resources for the next generation of cyber professionals.

Here is a list of Nevada universities that have created cyber centers:

- University of Nevada, Reno’s Cybersecurity Center: The Cybersecurity Center focuses on educational and research opportunities in cybersecurity and seeks to enhance Nevada’s cybersecurity readiness.143

- University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Cybersecurity Center: The Center is focused on educating and training cyber professionals in cyber defense to address the cybersecurity workforce shortage.144

Military Installations in Nevada

States are using their National Guard units to combat the growing national security threat of cyberattacks. National Guard units are being organized into cyber mission teams. Some are tasked with protecting state-level interests, and others are under the direction of US Cyber Command and are charged with protecting Department of Defense networks and national critical infrastructure.145 There are currently 3,880 National Guardsmen assigned to cyber service, spread across 59 cyber units in 38 states.146

Here are all the major military installations in Nevada:

- Naval Air Station Fallon, Fallon, NV

- Nevada Army National Guard, Carson City, NV

- Nevada Army National Guard, Clark County Army, Las Vegas, NV

- Creech Air Force Base, Indian Springs, NV

- Nevada National Guard, Reno, NV

- Naval Undersea Warfare, Hawthorne NV

- Nellis Air Force Base, Nellis AFB, NV

Appendix A

To Catch a Hacker: Third Way Policy Recommendations

Cybercriminals operate with a sense of impunity as only 0.3% of malicious cyber incidents see an arrest, according to our analysis of FBI reported data. What that means is that the United States is facing a massive cyber enforcement gap just as the cybercrime wave continues and malicious cyber activity that threatens our national security is becoming more common.

Domestic Enforcement Reform

- A Larger Role for Law Enforcement: Strengthen capacity building efforts so that law enforcement, enabled by diplomacy, can target the humans behind cyberattacks.

- A Cyber Enforcement Cadre: Address not only workforce shortages, but the way the cyber enforcement workforce is trained, incentivized, and retained.

- Better Attribution Efforts: Increase investments in research and development for attribution technology, better digital forensics, and prioritize efforts to build international alliances that improve timeliness and impact of attribution efforts.

- A Carrot and Stick Approach to Fugitives: Adopt a broader reward-based system to incentivize information sharing that can lead to arrests of malicious cyber actors balanced with the smart use of targeted sanctions.

International Cooperation and Coordination Reform

- An Ambassador-level Cyber Quarterback: Institute an ambassador-level cyber coordinator position at the State Department with a clear mandate and resources on cyber enforcement.

- Stronger Tools in the Diplomacy Arsenal: Expand the number and streamline processes for agreements with other countries that help bring cyber attackers to justice and continue to utilize the multilateral Budapest Convention.

- Better International Capacity for Enforcement: Support efforts to build the capacity of other countries on cybercrime investigations, while ensuring cybercrime and cybersecurity efforts are not used to suppress civil liberties and human rights.

Structural and Process Reform

- Better Success Metrics: Establish mechanisms to measure the scope of the cyber enforcement problem and the effectiveness of government efforts.

- Organizational Changes and Interagency Cooperation: Evaluate further needed policy changes to de-conflict the missions of the agencies responsible for cyber enforcement.

- Centralized Strategic Planning: Institute an overarching, comprehensive strategy for US cyber enforcement led by a senior official at the White House.

Appendix B

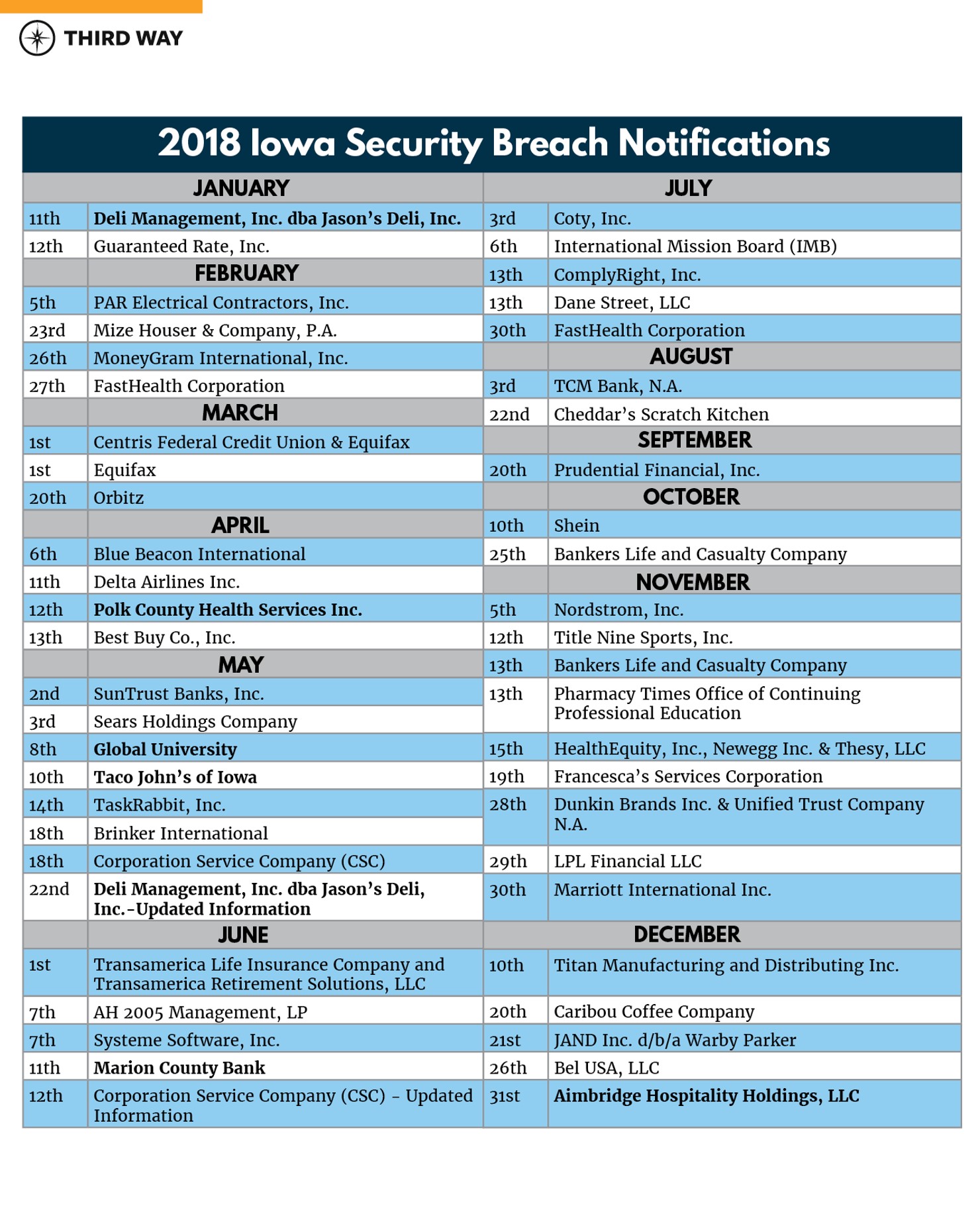

Iowa Data Breach Notifications

The Iowa Attorney General maintains a database online of all security breach notifications in the state since 2011. Iowa law requires anyone that encounters a security breach that affects at least 500 Iowa residents to report the breach within five business days after notifying affected people to the Attorney General’s Consumer Protection Division Director. The below chart is those companies that reported data breaches to the Iowa Attorney General in the year 2018. Companies bolded are local Iowa businesses.