Primer Published March 7, 2019 · 15 minute read

2019 Country Brief: China

The National Security Program

Takeaways

- China seeks to rival the United States on the global stage in economic, military, technological, and diplomatic terms. Contesting China’s growing influence is the foreign policy challenge that will define the future.

- Economy: Whether the United States or China sets the rules for global capitalism will determine how workers in the United States and globally will fare in the modern economy. Unlike pure communism of the past, China’s economic approach can coexist with Western capitalism. China is a legitimate and deserving economic power, but China’s history of manipulating its currency, stealing intellectual property, dumping steel and other products onto American markets, and subsidizing its own companies show China is not playing by the rules. America must stand up to these unfair economic practices. President Trump’s reckless trade war with China is the wrong approach and has cost US businesses billions of dollars in revenue.

- Military: China is challenging the United States’ military dominance in Asia, worrying our South Korean and Japanese allies and risking a regional arms race. The United States can support our allies through strengthened economic and military cooperation while avoiding direct military conflict with China.

- Technology: China‘s cyber capabilities are a national security threat to the United States. China has used cyberattacks not only to steal intellectual property from US companies, but also US military and intelligence secrets. The United States must protect against Chinese cyberattacks and bring Chinese cyber attackers to justice.

- Foreign Relations: While the United States and China are increasingly rivals, the two countries have many common interests and a history of working together. The United States needs to balance competition with cooperation to resolve issues that require global solutions.

Economy: China has a history of unfair trade practices that must and can be addressed without a devastating trade war.

Since it abandoned communism and embraced a market-based economy, China has taken advantage of our open, rules-based system of trade. It has subsidized Chinese exporters and stolen US intellectual property, preventing US firms from fairly competing in China. The result is an uneven playing field, with US workers and companies paying an unfair price.

For both sides to fully realize the benefits of trade, the United States must insist that China play by the rules. China must end its subsidies for Chinese exporters, as well as other unfair trade practices that give their domestic businesses an advantage in overseas trade. China must also allow US firms to fairly compete within the country. Because innovation and openness are the sources of our economy’s vitality, a balanced trade policy would address all the ways China takes advantage of the system. At the same time, the United States must invest more heavily in technology and innovation of its own and must strengthen cybersecurity against China’s espionage and theft of intellectual property. However, because our economies are so interlinked, a trade war is a lose-lose proposition.

In 2018, President Trump’s escalation of actions against China for its unfair trade practices turned into a trade war, which negatively impacted the US economy and American workers. The Trump Administration’s new tariffs on Chinese imports were a blunt and ineffective instrument that cost US businesses $6.2 billion in October 2018 alone.1 Despite President Trump’s claims that China is paying the United States for these tariffs, they are a tax on imported goods and, in many cases, that cost is passed on to American businesses and consumers.2 The trade war between the United States and China has involved a dramatic escalation of retaliatory measures on both sides, and has increased the US trade deficit with China to $55.5 billion, its highest level in 10 years.3 In December 2018, the United States and China negotiated a 90-day ceasefire to put a pause on the trade war.4 But, reflective of the dysfunction in this White House and the current state of the relationship with China, the statements released by the Trump Administration and the Chinese government after this agreement differed greatly. The effectiveness and durability of the agreement are unclear.5 Unfortunately, the damage from Trump’s trade war with China is already done and global markets have become increasingly volatile.6

United States cooperation with China to address these global crises grew even more complicated with the arrest of the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of Huawei, a Chinese telecom company that is the world’s second largest smartphone maker. Huawei has been accused of violating US sanctions on Iran. CFO Meng Wanzhou was arrested in Canada at the behest of US law enforcement in December 2018 and, at the time of writing, is pending extradition to the United States.7

The best way to rein in bad Chinese behavior is through international trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which would have set ground rules for other countries in Asia, putting peer pressure on China to conform.8 The TPP proved to be politically unpopular in the United States.9 However, other measures that fall short of a trade war could include limiting joint ventures with China in areas where they steal intellectual property, applying sanctions to industries that are subsidized and state-sponsored, developing market opportunities outside of China, and challenging China’s trade practices at the World Trade Organization.10

Military: China’s growing military power and muscular foreign policy are alarming US allies…and US war planners.

After World War II, the United States remained the dominant military presence in Asia to promote trade, security, and cooperation and to prevent the emergence of a central regional power like Japan or China. As China rises, it is challenging US presence and influence in the region. Everyone in the region has much to gain from cooperation and much to lose from conflict; thus, policymakers should seek non-military solutions to deal with the threats posed by China to the United States and its allies.

China aspires to return to the dominant position it enjoyed in Asia for thousands of years before going through a century of colonial rule. It has been translating its recent wealth into military power. Every year for two decades, China’s military budget increased by double digits, reaching $175 billion in 2018.11 While this still pales in comparison to the US defense budget—the Department of Defense requested $686 billion for fiscal year 201912—China’s increasing budget has allowed it to invest in new technologies aimed at deterring foreign aggressors while asserting its regional foreign policy aims.

While the United States and China were allies during World War II against the Japanese, once the Communist Party took control of China, the two countries broke off relations.13 After decades of internal turmoil post-World War II, during which China remained domestically focused, in the 1970s the country became more globally engaged and began to grow.14 Now China sees itself as a global power. At the 2017 Communist Party Congress, Chairman Xi Jinping declared that China should “take center stage in the world.”15

But China’s rise poses challenges for the United States:

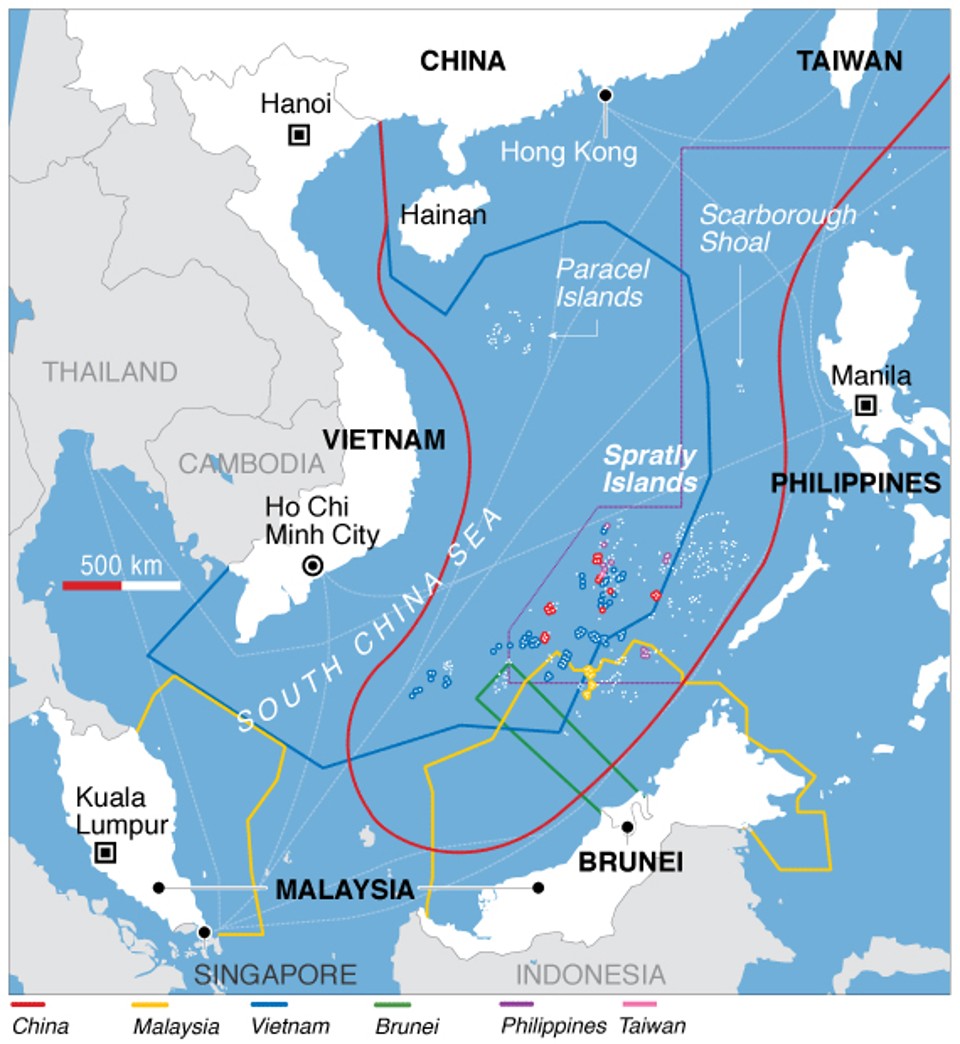

- A small standoff in the South China Sea could snowball into a major conflict. The South China Sea is a major geostrategic water lane through which $5.3 trillion in trade passes annually—30% of all global trade.16 Additionally, the US Energy Information Agency estimates that there are 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the South China Sea.17 China wants to dominate the South China Sea, arguing that the competing claims of Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, Brunei, and the Philippines should give way to its historical rights over the entire territory.18 For years, Chinese military vessels have been intimidating Vietnamese, Filipino, and Japanese fishermen and commercial vessels over a number of territorial disputes in the South China Sea and elsewhere, leading to worries that a major conflict could erupt.19

While the United States does not take a position on the final settlement of territorial claims, arguing it should be a matter of negotiation involving all parties,20 the potential for major conflict continues to grow. To cement its claims, China has been building and militarizing islands in the South China Sea. These formations are part of a broader strategy to make it difficult for the US military to operate in the region during a conflict and to form a buffer around China.

The United States has mutual defense treaties with Japan and the Philippines.21 Should conflict between China and these countries come to a head, the United States would be obligated to consider military action, making conflict more complex and costly.22

- The United States must reassure its regional allies and partners to combat Chinese aggression.While the United States initially assumed a dominant military position in Asia to prevent the reemergence of Japan as a military power after World War II, in recent years America’s presence serves as a check on China. In addition to Japan and the Philippines, the United States also has a mutual defense treaty with South Korea.23 Other countries in the Asia-Pacific region also look to the United States to counterbalance China. Japan, alarmed by China’s growing military power, revised the country’s pacifist constitution and began building up its armed forces. The United States and the Philippines agreed in 2014 to strengthen US military presence in the Philippines.24 South Korea and the United States have regularly conducted joint military exercises (although President Trump committed to North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un to end these exercises in their June 2018 summit regarding the North’s nuclear weapons).25 Besides these treaty allies, Vietnam has also strengthened defense ties with the United States.26 While the United States remains essential to the stability of the regional order—including the free flow of trade—as China grows in strength, the United States must reassure its allies and partners of America’s ability and willingness to temper Chinese influence.

- To stay ahead of China, the United States must invest in technology.China’s investments in technology are not merely aimed at catching up to the United States; in some areas, China seeks to become a leader. The most important new domains of Chinese military technological competition with the United States are Artificial Intelligence (AI) and quantum computing, both of which pose serious threats to America’s competitive edge. Major figures from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt to former Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work warn that China will soon overtake the United States in AI, which the Chinese believe will not only dramatically boost economic growth, but also change the entire character of warfare.27 AI can improve autonomous systems, war gaming, simulation, and information processing.28 China has also invested in a $10 billion quantum computing center to support military and national defense efforts, whereas the United States has no equivalent project.29 Quantum computing threatens to break widely used encryption standards that safeguard information in the public and private sector.30 If the United States falls behind in the development of AI and quantum computing, China could hone battlefield advantages that will limit our ability to win a war, defend our allies, and preserve the regional order we built after World War II.

In addition to these evolving security threats, China has continued to invest heavily in diversifying and growing its nuclear weapon and ballistic missile programs—which pose a threat to the United States and its allies should conflict ever erupt.31 The country has also used economic investments around the globe, through its Belt and Road Initiative, to push its agenda and gain a strategic foothold in many regions, particularly Eurasia, Africa, and Latin America.32

There is no mistaking China’s intentions to challenge US dominance in Asia and the world. To counter the threat of China militarily, the United States must continue to look for ways to strengthen our Asian alliances, including through the provision of ongoing economic and military assistance to these countries. This assistance must be focused on deterring Chinese aggression and strengthening the ability of the United States to respond if needed. The United States must also ensure that the US military and diplomats have the needed resources and capabilities to deter and rapidly respond to Chinese aggression against the United States and its allies. But if we wish to truly continue to play a dominant role in Asia and around the globe, the United States must also get its house in order and invest more heavily in strengthening its own technological capabilities.

Technology: China uses cyber capabilities to steal our secrets.

Beyond the threats that China poses in Asia, it is using its cyber capabilities to challenge the United States globally. China aggressively uses its cyber capabilities to steal not only intellectual property that belongs to US companies, but also US military and intelligence secrets. In 2015, China hacked the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), stealing the private information of 22 million US citizens.33 More recently, it is suspected of being responsible for a hack on the Marriott hotel chain, which is estimated to have stolen the personal information of over 500 million customers.34

China also steals military technology while cultivating contacts throughout the defense industrial supply chain and the US government. These tactics are part of their “Made in China 2025” strategy, which aims to add to China’s economy by focusing on high-tech manufacturing sectors like aeronautics, robotics, and clean-energy vehicles.35 By stealing secrets from US manufacturers, Chinese state-owned enterprises can skip the time and capital normally required for research and development of these technologies.

All nations seek to steal national security secrets, including the United States. But the US is underinvesting in cyber capabilities and security relative to the high stakes, particularly since US technology is vulnerable to Chinese state-sponsored hacking.

The US economy depends on an open Internet, while China is increasingly building separate and isolated systems. But cybersecurity is also one area where the two countries could cooperate and establish joint rules. In 2015, President Obama and Chairman Xi Jinping agreed that their governments would not knowingly conduct economic cyber espionage against each other—though not government espionage—which led to a dramatic drop in cyber espionage the following year.36 The United States and China also agreed to cooperate against hackers, leading to the arrest of the Chinese nationals who broke into OPM in 2015.37 This shows that, by cooperating, we may protect our interests while avoiding costly escalation.

However, in the Trump Administration, Chinese hacking activity has been on an uptick. The cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike has identified China as the most-prolific nation-state threat actor attacking different sectors of the US economy. In response, the US Department of Justice under the Obama and Trump Administrations has indicted a number of Chinese citizens, including Chinese intelligence officials, for their role in malicious cyber actions against the United States. These indictments are critical to demonstrating that the United States will not tolerate China’s behavior, which has often crossed the line from regular intelligence practices to criminal activities. An important law enforcement component of the US response to these cyberattacks must also be to continue to pursue criminal cases against Chinese cyber attackers, when warranted, to deter future attacks. But law enforcement efforts must also be coupled with further diplomacy to address China’s hacking.38

The United States remains woefully unprepared for Chinese cyberattacks that target critical infrastructure—including election infrastructure. China could learn from Russia’s playbook and interfere in our elections, as it has already been accused of meddling in Australia and New Zealand’s domestic politics.39 Congress has an opportunity to draw attention to this important issue while devoting more resources to securing US networks and infrastructure from Chinese hacking.

Foreign Relations: American cooperation with China is necessary, where possible, despite China’s threats to the United States and its allies.

China is the largest country in Asia and will be a necessary partner to resolving global threats in Asia, like North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Despite the global sanctions placed on North Korea, China remains North Korea’s largest and most important trading partner. In resolving tensions with North Korea, the United States must both leverage China’s relationship with the country and hold China accountable for its unfair trade practices and security threats to the United States.40

Both China and the United States have permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council and thus have the ability to veto any decisions the Security Council tries to take. Because the United States needs China’s cooperation at the United Nations to solve many of the globe’s toughest problems—including North Korea, Iran, and countering terrorism—China’s cooperation is essential.

Climate change was also a key area of cooperation between the United States and China in the past, though President Trump foolishly withdrew the United States from the historic Paris Agreement aimed at tackling this global threat. Some US states have continued to push forward on the issue, and are maintaining cooperation with China on mutual climate goals.41

Congress can highlight the tensions and opportunities in the US-China relationship and look for opportunities to boost cooperation between the two countries when possible.

Conclusion

The security and economic challenges in the US-China relationship are considerable, but there is also great opportunity. As both nations increase their trade links, innovate, and create new scientific knowledge, all of humanity can benefit. Given the security and economic stakes involved, both governments must think long term. The United States and China can manage disputes and competition through candid diplomacy and ensuring close military-to-military communication to avoid unnecessary escalation that could inflict needless damage on both countries.