Primer Published March 7, 2019 · 18 minute read

2019 Country Brief: Afghanistan

The National Security Program

Takeaways

The United States entered Afghanistan more than 17 years ago, following the 9/11 attacks. The goal was to prevent the country from returning to a terrorist safe haven that could be used to launch attacks on the American homeland. However, recent evidence and history shows the US military-driven strategy of training, advising, and assisting Afghan military forces has not worked.1 The Afghan government controls roughly 55% of the country—down from 72% in 2015—with the remainder under the control of insurgent groups like the Taliban.2

A political settlement to the conflict in Afghanistan is the only way to create lasting peace in the country and reduce the terrorist threat to the United States. The Trump Administration is attempting to negotiate a peace agreement between the United States and the Taliban without the involvement of the democratically elected Afghan government.3 President Trump has said US troops will be withdrawn from the country as progress is made in these negotiations.4 Congress must now conduct proper oversight by pushing for: 1) an agreement leading to a political settlement between the Afghan government and the Taliban; and 2) a comprehensive exit strategy that improves economic development and governance in the country.

Since the start of the United States’ war in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, Congress has largely abdicated its constitutional oversight role over US troop deployments and “its power of the purse” authority over military spending. As the US government works to negotiate an agreement with the Taliban, Congress must reassert its authority in decision making around US troop deployments by:

- Rescinding its 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) permission slip granting the executive branch unrestrained counterterrorism authority and consider a new, narrowly tailored authorization for US counterterrorism efforts.

- Ending the blank check for military spending through the use of the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding which has operated as a “slush fund” for defense spending.

- Aligning the Department of Defense’s (DoD) budget with its mission. The Trump Administration plans to withdraw US troops from Syria and Afghanistan while requesting an increase in the defense budget to $750 billion. If the US withdraws from military engagements, defense spending should also be reduced.

- Establishing a commission to evaluate the US mission in Afghanistan and understand what was achieved after 17 years in the country.

The United States’ history in Afghanistan includes America’s longest war.

United States involvement in Afghanistan has a tumultuous history. In the 1980s, the United States backed insurgents against the Soviet occupation. Then, after the Soviet withdrawal in the 1990s, the Taliban took power, bringing repressive rule and establishing a safe haven from which Al Qaeda planned and executed the 9/11 attacks. In response to those horrific attacks, in 2001, the United States deployed troops to Afghanistan and successfully drove out Al Qaeda and the Taliban regime, eventually paving the way for elections.

But from 2002 to 2009, in the words of former Defense Secretary Robert Gates, “resources and senior-level attention were diverted from Afghanistan” to Iraq, interrupting US efforts to rebuild Afghanistan.5 It was not until the start of President Obama’s tenure in 2009 that the United States shifted its focus back to Afghanistan, sending an additional surge of 30,000 troops to suppress the Taliban insurgency and stabilize the country.6 Civilian deaths in Afghanistan nevertheless increased after this period.7

In 2014, at the end of Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s tenure and after years of tense relations with his administration, the United States sought a political solution to a disputed election and helped broker a national unity government between President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah. Ghani, a former Afghan Finance Minister with a doctorate from an American school and decades of experience as an academic and World Bank staffer, was elected and continues to serve as president. Abdullah Abdullah, who previously served as Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister, became Chief Executive. The parties did not include the Taliban, a fundamentalist group that continues fighting to this day.8

On January 1, 2015, NATO ground forces, including American troops, officially ended their combat mission in Afghanistan, replacing it with a train-and-advise mission. In November 2017, NATO Allies and partners decided to set the number of troops in Afghanistan to 16,000 personnel. Prior to that decision, in June, President Trump had already reversed his campaign pledge to withdraw from Afghanistan and approved a plan by then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis to send 3,000-5,000 troops to advise Afghan forces.9 This brought the number of US forces to 14,000—just a fraction of President Obama’s surge of 30,000 troops in 2009, which nevertheless failed to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table or fundamentally alter the security situation.10 Currently, there are still 14,000 troops in the country.11 According to DoD, over 2,400 US military personnel and civilian employees have been killed in support of US military operation in Afghanistan.12 From 2002 to 2017, the United States Congress has appropriated or allocated more than $900 billion for various State Department and Pentagon programs to support the Afghan security forces.13

Despite President Trump increasing the American military presence in Afghanistan, terrorist attacks have continued and the Taliban-led insurgency has raged on, expanding the group’s territorial gains. The Afghan government made attempts in the summer of 2018 to quell this violence, offering two ceasefires to the Taliban.14 Instead, attacks by the Taliban have continued and the group now controls more territory in Afghanistan than any time since its removal from power in 2001.15 Attacks by Al Qaeda, which organized the attacks on 9/11 from Afghan territory under the patronage of the Taliban, and by an affiliate of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) have also led to devastating casualties in Afghanistan, raising concerns that terrorist groups could continue to make further gains in the country.16

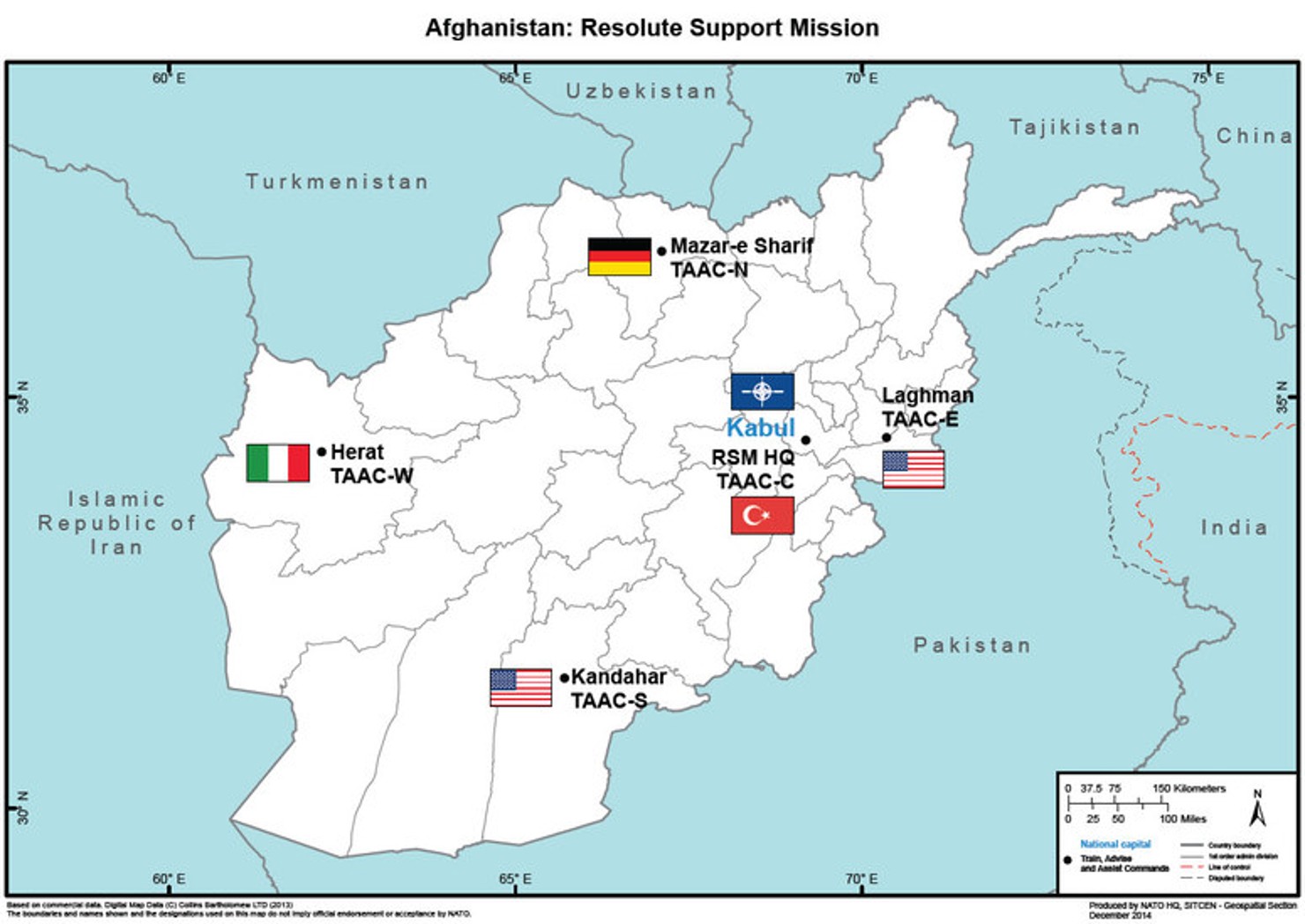

The United States’ NATO allies have been critical partners in stabilizing Afghanistan. These are the NATO bases currently in the country. Source: “Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan.” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 18 July 2018. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_113694.htm. Accessed 17 Feb. 2019.

A political settlement is the only way to create peace in Afghanistan and reduce the terrorist threat to the United States, but Congress must play an oversight role in negotiations.

A political settlement to the conflict in Afghanistan is the only option for creating a lasting peace in the country and reducing the terrorist threat to the United States. While the Trump Administration is moving forward with direct negotiations between the United States and the Taliban, President Trump has said he will withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan if progress is made in these negotiations.17 Congress must conduct proper oversight of this process to ensure the conditions are set for a political settlement between the Taliban and Afghan government. The US government needs a comprehensive exit strategy for troop withdrawal. Congress should prioritize a strategy that shifts to non-combatant support for governance through economic development.

In January 2019, US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, announced that the United States had reached a framework for peace talks with the Taliban without the Afghan government. The framework reportedly includes a commitment from the Taliban to a ceasefire and to subsequently negotiate directly with the Afghan government.18 This is a strategy shift for the US government, which has historically insisted that talks be “Afghan-led” and directly held between the Afghan government and the Taliban. The decision by the Trump Administration to move forward with these talks is reportedly a result of the realization that Trump’s military-driven Afghan policy was not working and has only led to more violence. Despite President Trump’s stated intent to withdraw US troops based on progress in the negotiations, no timetable has been announced.19

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani is running for reelection in the upcoming April 2019 presidential elections. There is concern this could lead to more violence by the Taliban and to political infighting that could distract from the peace process. As such, the Trump Administration has called for these elections to be delayed; however, the Afghan government has strongly opposed this request.20

Any progress in reaching a political settlement in Afghanistan is positive, and it is certainly time for US troops to come home. But Congress must exercise its proper oversight during these negotiations and hold the Administration accountable to two key priorities: lasting peace and a US military withdrawal.

First, the United States and Taliban must agree to establish conditions for a political settlement between the Afghan government in Kabul and the Taliban. The Afghan government is not at the table in the US negotiations with the Taliban, nor are any groups that will be most impacted by a peace agreement (e.g., women and women’s groups).21 Therefore, it is questionable how effective any agreement will be. Afghans should be involved in any political settlement that sets the future direction of their country.

Second, as part of a peace agreement, the United States must develop a comprehensive exit strategy for US troop withdrawal and shift to non-combatant support through diplomatic and humanitarian efforts. Without engagement on both governance and development, Afghanistan could return to the chaos of the 1990s and give rise to terrorist safe havens. The withdrawal strategy should support efforts of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) to secure their country and reduce corruption, through the provision of training, advice, and assistance.

Ultimately, long-term peace between the Taliban and Afghan government coupled with effective governance that promotes rule of law and reduces corruption will keep Afghanistan from backsliding into a terrorist safe haven—the core US priority in the country.

As the United States works to negotiate peace in Afghanistan Congress must also reassert its responsibility to make decisions on US troop deployments.

Since 9/11, Congress has deferred to the president on where the United States deploys troops and how military operations are conducted. But after 17 years of deference and no end in sight for the conflict, this approach is not working. Congress must reassert itself by rescinding its war authority permission slip and blank check for military spending that the Executive branch has taken for granted.

1. Congress should rescind its 2001 AUMF permission slip granting the Executive branch unrestrained counterterrorism authority and consider a new, narrowly tailored authorization for US counterterrorism efforts.

Congress deferred its constitutional authority over matters of war 17 years ago by granting the executive branch a permission slip for unilateral military action. Congress should assert its authority as a co-equal branch of government, rescind the 2001 AUMF, and debate the merits of a new, narrowly tailored counterterrorism authority. The Constitution provides in Article I, Section 8 that “Congress shall have the power to declare war.”22 Congress used this constitutional power when it authorized the 2001 AUMF. After the attacks on 9/11, Congress authorized the president to use force against the people who initiated those attacks. Since then, presidents have used that authority to combat Al Qaeda and its affiliates around the world.

Section 2(a) of the 2001 AUMF authorizes the use of force in response to the 9/11 attacks:23

Sec. 2. Authorization For Use of United States Armed Forces.

(a) In GENERAL.—That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

The 2001 AUMF was intended to give the president authority to enter into an international armed conflict in Afghanistan against Al Qaeda and the Taliban. The US government believed that Taliban-controlled Afghanistan was harboring terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda, who were responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The US government should have the “necessary and appropriate” authority to exercise its right to self-defense, but there should be limitations on the authority of the president to take military action without congressional approval. The text of the AUMF does not name or specify terrorist organizations nor provide geographic limits. The Obama Administration interpreted the scope of the 2001 AUMF to fit within the president’s Article II powers as commander in chief and chief executive to use military force against those who pose a threat to US national security.24 This interpretation expanded the scope of the 2001 AUMF from authority to go after Al Qaeda and the Taliban to including “associated forces” of those organizations.

Currently, the United States is engaged in counterterrorism operations across the globe, far exceeding the original intent of the 2001 AUMF.25 The 2001 AUMF has been used to deploy US troops in Afghanistan, the Philippines, Georgia, Yemen, Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iraq, Somalia, and others.26 Presidents have claimed that the 2001 AUMF also allows them to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) even though ISIS was not involved in the 9/11 attacks.27

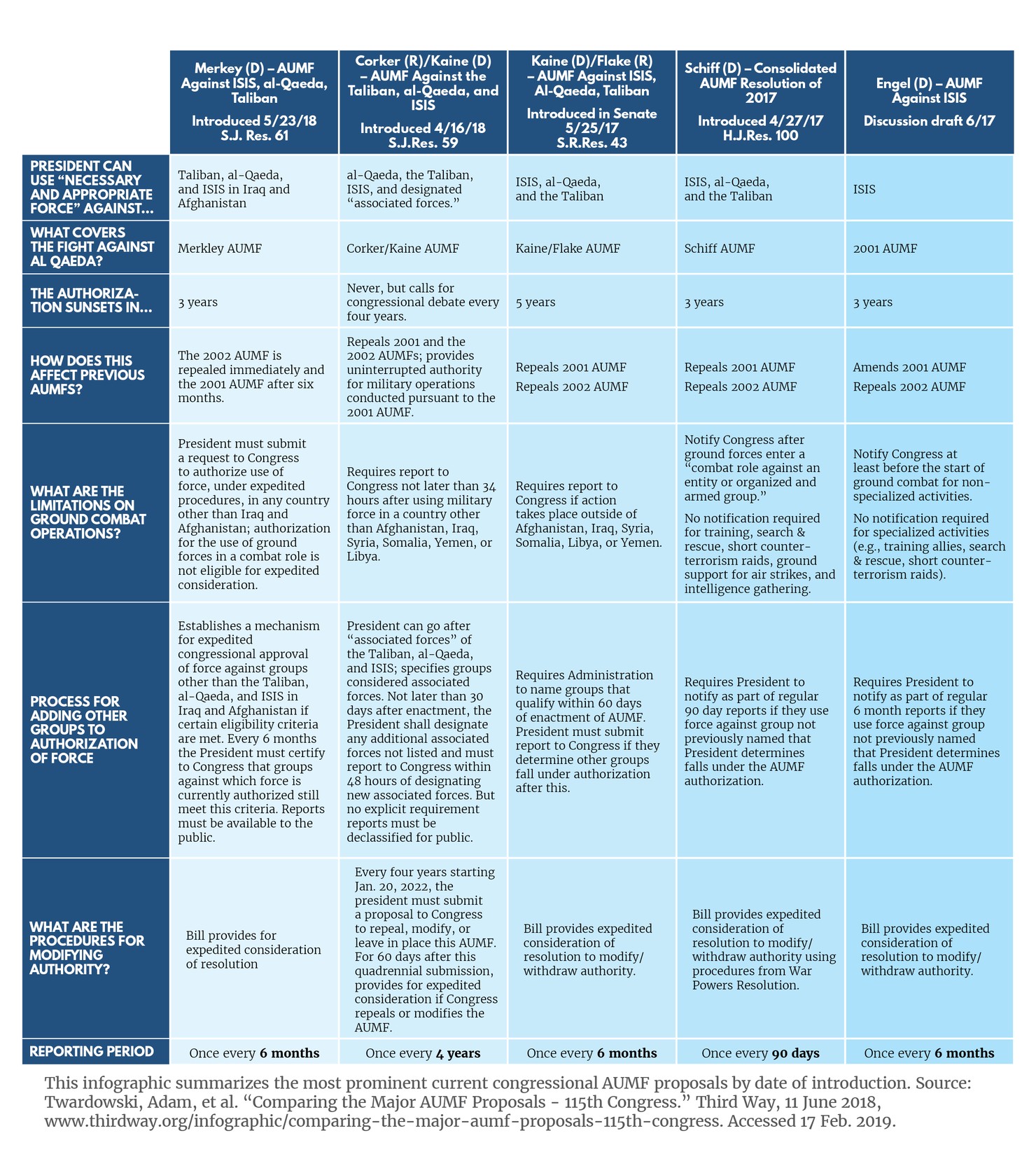

Most congressional members have never had to take a stance on US military operations, despite the changing nature of national security threats. Congress has very little ability to constrain the president’s use of military force because it has not passed a new AUMF since the 2002 Iraq AUMF.28 Several bills were introduced in the 115th Congress to define the president’s authorities in a new AUMF. These bills deserve further consideration in the 116th Congress.29 Congress should now make it a top priority to approve a clear statement of where the president is authorized to use force and against whom.

Debating a new AUMF would reassert Congress’s constitutional authority over matters of war, limit the potential for unilateral action and unintentional escalation caused by the president, and encourage the series of checks and balances on presidential military authority intended by the Founding Fathers. Any new AUMF must be narrowly tailored and give Congress the clear authority over where the executive branch is conducting military operations, articulate the targets for these efforts, and include an expiration date to prevent authorities passed 17 years ago from being continuously used without any input from Congress.

2. Congress should end the blank check for military spending through the use of the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding. It has been used as a “slush fund” for emergency defense spending and is not subject to spending caps under the Budget Control Act of 2011.

As Congress rescinds its war authority permission slip, it should also revoke its blank check for military spending by eliminating Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding. OCO provides the Pentagon with funding not subject to sequestration mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), a 2011 law that capped federal defense and non-defense spending and was designed to reduce defense spending by $1 trillion over 10 years.30 Congress has the constitutional “power of the purse” to make decisions on funding for the federal government.31 OCO funding has been used since the 9/11 attacks to provide the Pentagon with “emergency” war funding for US operations in Afghanistan, as well as in other places such as Syria and Iraq.32 President Trump has stated he intends to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan33 and Syria34—as a result, the use of OCO funding should be eliminated.

There are two major categories of defense funding that are typically considered by Congress during the federal budget process. The first is the “base budget,” which covers funding for activities that DoD would conduct if US forces were not engaged in overseas operations. The costs for these activities can be forecasted annually; therefore, DoD can incorporate these costs into their annual budget request. The DoD base budget falls under the spending limits set by the BCA.35

The second major category is known as OCO funding, which is excluded from the spending limitations in the BCA. OCO funding was established as an “emergency” fund for war-related costs because war-related costs cannot be forecasted. It largely ballooned after the 9/11 terrorist attacks to cover spending for overseas combat operations such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan.36 The majority of OCO funding goes to DoD, with only a small portion going to the Department of State.37It has often operated as a type of “slush fund.” With the base budget under spending limitations, the Pentagon moves traditional base budget activities to OCO as a loophole to sequestration. The Pentagon currently uses roughly $30 billion of OCO funding for base budget activities, often referred to as “enduring costs.”38 This is problematic because parking base budget activities in OCO funding hides the true cost. These costs are not included in DoD cost projections during budget requests, nor in overall federal spending and deficit projections.39

OCO has ballooned over the years. Between 1970 and 2000, non-base budget funding only accounted for about 2% of DoD’s total spending. In 2007 and 2008, OCO funding peaked at 28% ($205 billion in 2007 and $222 billion in 2008).40 Since 2006, $1.81 trillion has been spent on OCO funding alone.41 OCO funding has turned into a secondary defense budget.

With President Trump’s stated desire to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan and Syria, the blank check for OCO funding must end. Congress must work to fold all Pentagon spending back into the DoD base budget so that it can adhere to BCA limitations.

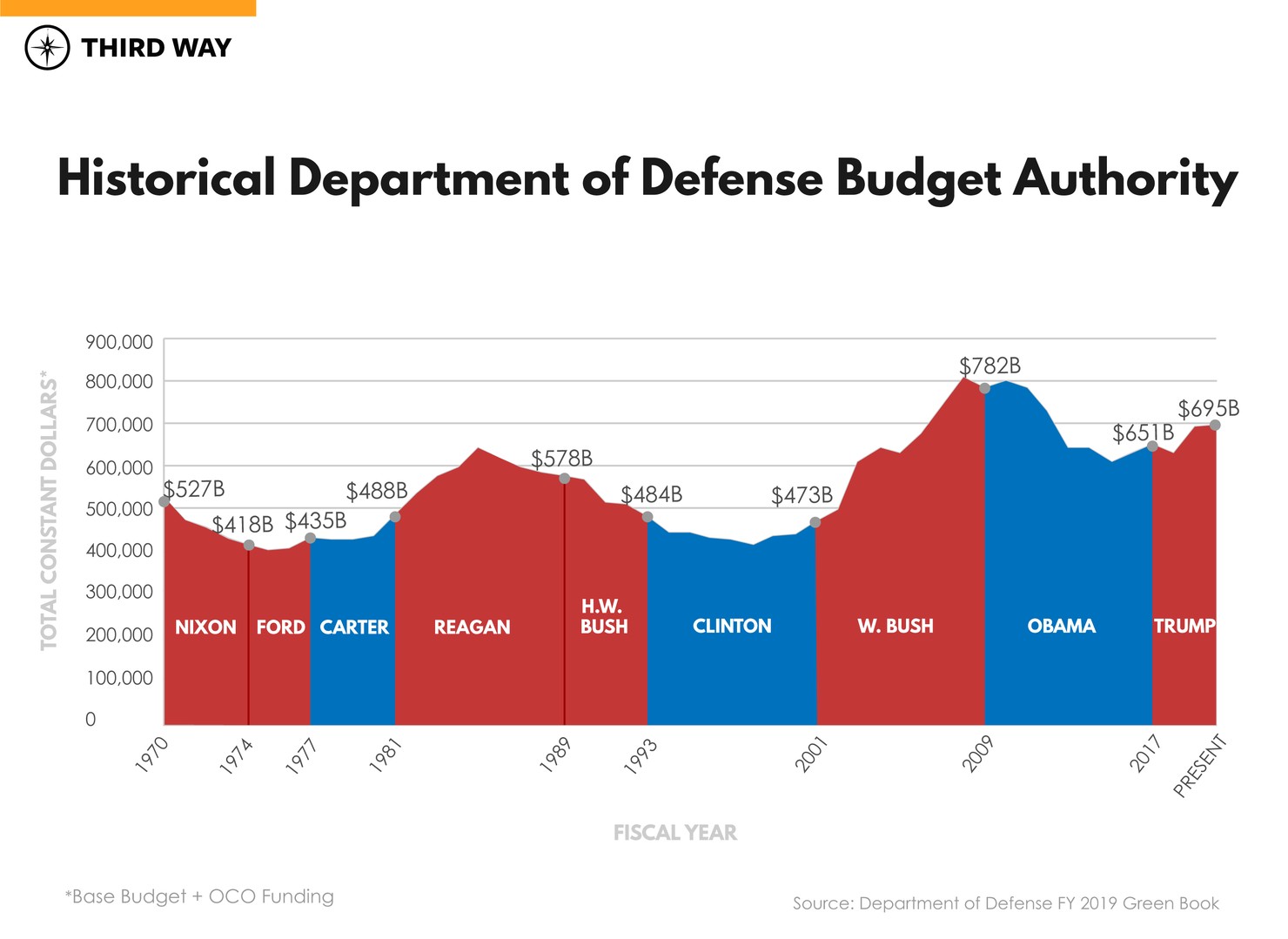

3. DoD’s budget should be aligned with its military commitments.

The size of the defense budget should follow its mission obligations. President Trump recently announced the withdrawal of US troops from Syria and his intention to withdraw from Afghanistan once a peace agreement is reached.42 This would end two major US military operations abroad. As the Pentagon is winding down military engagements, they are also requesting an increase in defense spending in fiscal year (FY) 2020. Members of Congress should use their appropriations and authorizing authorities to reject the Trump Administration’s call to increase defense spending to $750 billion.43 The defense budget should align with the department’s mission; if US troops withdraw from global conflicts, military funding should also be reduced. With the withdrawal of US troops from Syria and Afghanistan, Congress should look to strategically shift to non-combatant support for governance. Congress should evaluate whether America’s diplomats and development entities have the needed funding to continue their vital work in these countries.

The defense budget should not operate like a one-way ratchet, which only goes up. If requested, President Trump’s reported FY 2020 defense budget of $750 billion would be the largest since the height of the Iraq war.44 There is historical precedent to wind down the defense budget after the military scales back its operations. In 2013, President Obama reduced funding at the Pentagon as the United States scaled down operations primarily in Iraq and Afghanistan.45 Congress should follow the same precedent now and ensure the DoD budget is aligned with its global combat missions.

Congressional Democrats should use the upcoming budget and nomination hearings for a new Secretary of Defense to inquire why DoD is scaling up their budget while withdrawing from Syria and Afghanistan. In particular, during these processes, Congress must question:

- What is the exit strategy for Afghanistan and Syria, and how will a withdrawal of a US military presence in these countries impact US national security?

- Why is a large increase in defense spending required if US troops are withdrawing from these conflicts, and can this money be better spent?

4. Congress should establish a commission to evaluate the US mission in Afghanistan to understand what was achieved after 17 years in the country.

The US military intervention in Afghanistan has lasted more than 17 years. The United States supported a number of development and economic objectives in the country, but there are questions surrounding what has been achieved. To help assess these questions, Congress should work to establish a commission to evaluate the United States’ war in Afghanistan and report on the lessons learned to policymakers. The commission should consist of former military personnel, diplomats, development experts, and civil society leaders, including women’s and human rights groups.

The United States has supported the Afghan government over 17 years, with the objective of stabilizing the country and reducing the conditions for a terrorist safe haven. There are still questions about whether the United States has achieved any of its security objectives. The US government needs to take a good hard look inward as to what lessons it has learned and how those lessons should impact decision making on the use of military force in the future.

Without a comprehensive look at the failures and successes of US operations in Afghanistan, the country risks repeating the same mistakes in future decision making around when, where, and how US missions are conducted around the globe.

Conclusion

The United States entered Afghanistan 17 years ago after the 9/11 attacks to prevent the return of terrorist safe havens that can be used to launch attacks on the American homeland. Now, the United States is negotiating with the Taliban to end US military operations and withdraw US troops from the country. Congress must conduct proper oversight of these negotiations and push for: 1) a political settlement between the Afghan government and the Taliban; and 2) a comprehensive exit strategy that improves economic development and governance in the country.

As the US government works to negotiate an agreement with the Taliban, Congress must also reassert its authority in decision making around US troop deployments by:

- Rescinding the 2001 AUMF permission slip;

- Ending the blank check for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding;

- Decreasing defense spending to match scaled-back military missions abroad; and

- Forming a commission to evaluate the successes and failures of the 17 year US mission in Afghanistan.