Memo Published June 30, 2025 · 14 minute read

Winning the Global Nuclear Market: Priorities for US Export Financing Agencies

Alan Ahn, Rowen Price, & Christel Hiltibran

Key Takeaways

- The reauthorization deadlines for EXIM and DFC create urgency to not just extend their mandates, but fix the shortfalls that prevent them from being able to more fully engage on nuclear projects.

- From early-stage USTDA engagement to financing for a mature construction project, US agencies have the opportunity to box out adversaries by advancing relationships based on nuclear cooperation.

- Strong bipartisan support remains for the US nuclear sector and its competitiveness abroad, and so now Congress needs to act to empower these agencies with robust tools and authorities to advance American exports.

Why Do We Need To Strengthen US Nuclear Export Financing Now?

In a period of soaring demand for nuclear energy worldwide, it is increasingly vital to leverage key federal agencies to help finance capital-intensive US civil nuclear exports, including the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM) and the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC).

Our geopolitical rivals, such as China and Russia, are aggressively cornering this critical global market, bringing state-backed financing to facilitate export deals and exert influence over client nations for decades. To counter Russia’s and China’s growing influence, the US must offer its own robust financing alternatives. Agencies such as EXIM and DFC must play crucial roles if we are to be competitive internationally in nuclear energy, and they must work in coordination from start to finish with other agencies in the export ecosystem like the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA). However, these agencies are currently constrained by their existing statutory constructs and authorities. Fortunately, both EXIM and DFC are up for Congressional reauthorization, presenting a timely opportunity to strengthen their authorities and flexibility, along with that of USTDA.

Despite our world-class reactor technology and long history of operational and regulatory excellence, the US simply can’t compete with China’s and Russia’s attractive financing terms. We’re not losing on merit—we’re losing on finance. Failure to take advantage of this current window of opportunity to strengthen US export financing will hand nuclear energy markets directly to our adversaries and competitors, and threaten global standards of safety, security, and nonproliferation.

Why is the international nuclear market so important?

- The emergence of artificial intelligence and other energy-intensive sectors means that the global market for nuclear energy is projected to be larger than previously estimated: 2024 Map of the Global Market for Advanced Nuclear: Future Demand is Bigger Than Ever

- Our geopolitical rivals, China and Russia, are aggressively engaging overseas markets in advance: 2023 Map: The World Wants Nuclear Energy. China and Russia are Racing Ahead

- International markets provide critical added “runway” to help commercialize US advanced nuclear technologies and get them to cost maturity, and US advanced nuclear technologies can’t reach commercial scale without international markets: How EXIM Can Power American Nuclear

- Nuclear exports establish and reinforce long-term diplomatic relationships with key international allies and partners: Atombridge: Strengthening the US/UK Special Civil Nuclear Relationship

- US global competitiveness supports America’s ability to shape the strongest international norms in nuclear safety, security, and nonproliferation: Fully Fueled: Strengthening America's Nuclear Toolkit

Fixing US Export Financing

US policymakers on both sides of the aisle recognize the importance of US nuclear export financing tools. The first Trump Administration authorized DFC and later removed its prohibition on financing nuclear energy projects. Under President Biden, the EXIM Board of Directors launched a small modular reactor (SMR) Financing Toolkit at COP28, offering a new suite of financing tools for SMR exports, to help position US companies competitively in the global nuclear market. These activities are encouraging, but they’re not enough if the US wants to prevent China and Russia from boxing the US out of the market. Despite existing momentum, these financing agencies lack the statutory authority and policy direction to more fully support US nuclear exports. Congress needs to strengthen US financing entities and ensure their maximum effectiveness in supporting nuclear export projects. The top priority is to reauthorize DFC and EXIM in 2025 and 2026, respectively, providing opportunities to make these tools even more effective.

The Export-Import Bank

EXIM is the official export credit agency (ECA) of the United States and has had a long history of involvement in civil nuclear transactions overseas, providing financing for US nuclear energy exports going back multiple decades. More recently, EXIM has been deeply engaged in moving the needle forward for prospective international deals: in addition to the SMR toolkit announced at COP28, EXIM issued a $3 billion letter of interest (LOI) for potential US SMR exports to Poland in 2023 and approved a loan worth $98 million to advance a front-end engineering and design (FEED) study for a US SMR export project to Romania in October 2024.

EXIM has a massive balance sheet, with a statutory cap of $135 billion in loans. But as of late 2024, it was only utilizing a quarter of that authority—$34.2 billion—leaving significant capacity untapped. Furthermore, because of the fees that EXIM charges, the agency is self-funded and often returns a dividend to the US Treasury.

However, the agency remains constrained due to statutory restrictions and outdated policies, many of which stem from decades-old partisan conflicts over the fate of EXIM. Reauthorization presents a tremendous opportunity to address these challenges, just as global demand is surging and the administration has signaled its intentions to robustly use EXIM and other financing agencies to promote US exports worldwide.

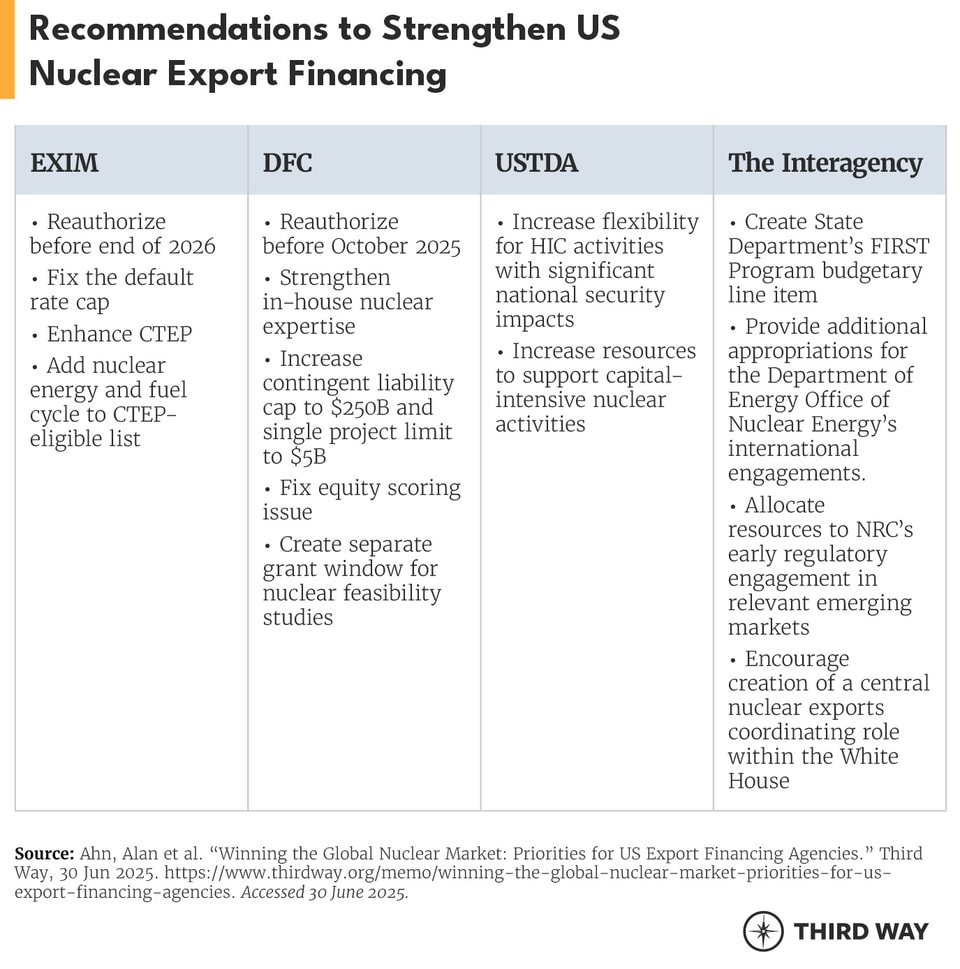

EXIM Recommendations

- Reauthorize EXIM for at least another seven years: Congress must reauthorize EXIM by the end of 2026. The reauthorization should be at least as long as the current authorization to provide certainty for longer-term projects, but longer authorizations will create even more stability as EXIM continues to support US national security and competitiveness through big-ticket export financing.

- Address the default rate cap issue: Under current law, if 2% of EXIM’s total portfolio is in default (i.e., 90 days late on payments), then EXIM would be sharply limited in authorizing new transactions. This rate cap is uniquely restrictive among global ECAs, meaning none of EXIM’s international counterparts face this same constriction. This restriction discourages EXIM from backing important but capital-intensive projects like nuclear exports due to default risk. This issue absolutely must be addressed in EXIM’s upcoming reauthorization. There are several potential solutions: raising the default rate cap, allowing the EXIM Board of Directors to exempt transactions from default rate calculations, exempting transactions within certain accounts or carve-outs entirely, mitigating the consequences of hitting the default rate cap (e.g., phased limitations on lending authority rather than a freeze), etc.

- Enhance the China and Transformational Exports Program (CTEP): The China and Transformational Exports Program (CTEP) is a key initiative to strengthen US global competitiveness in strategic economic sectors (Transformational Export Areas) and against Chinese-backed entities and state-owned enterprises. CTEP affords eligible transactions access to enhancements and flexibilities in rates, loan tenors, content, and other policies, etc. While CTEP is a powerful tool in EXIM’s arsenal, more can be done to enhance the program. Exempting all CTEP transactions from default rate calculations through establishing a CTEP carve-out, increasing the target amount for CTEP (currently $27 billion), including a national security/interest mandate, and enhancing existing flexibilities on content and other policies would greatly strengthen the program’s potency.

- Expand the list of Transformational Export Areas: Among other key technology sectors, nuclear is not included as a Transformational Export Area that is eligible for CTEP benefits. Statutory inclusion of nuclear energy as a Transformational Export Area (or expanding the definition of “renewable energy” to include all clean energy technologies and other critical energy infrastructure, such as grid and transmission) is highly recommended.

The International Development Finance Corporation

The BUILD Act, signed into law during the first Trump presidency, established the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) as a tool to provide debt financing, equity, insurance, and technical assistance for international projects to kickstart private US investment. Its activities focus on development and national security priorities—priorities that directly align with demand for US nuclear technology around the world. One of DFC’s most powerful tools for nuclear projects is its direct equity capability, which reduces the total project cost burden on potential buyers and makes US products more attractive.

DFC has significant potential to add value to capital-intensive nuclear projects, but with few exceptions has yet to engage directly on US nuclear exports, despite having the tools to do so. DFC has the flexibility to operate in high-income countries (HICs) in Europe and Eurasia on projects that improve energy security by reducing reliance on Russian supply. Broader country eligibility allows the agency to take on projects in advanced economies that are more likely to have near-term plans for nuclear energy deployment. DFC lifted its ban on financing nuclear projects five years ago and has since signed letters of intent to participate in US nuclear export projects. However, it has not yet made the specific commitments that would strengthen US reactor vendors’ positions in high-stakes negotiations with partner countries. Strengthening DFC will help create some certainty of US financial support for customers.

DFC Recommendations

- Reauthorize DFC for at least another seven years: First and foremost, Congress must reauthorize DFC by the end of FY25 for it to continue playing a role in exports of national interest. Seven years matches the current length of time for reauthorization, but the longer it is sure to have authority, the more certainty there will be for lengthier, more complex nuclear projects. Congress should aim for the longest authorization mandate possible.

- Improve in-house nuclear expertise: Since lifting its nuclear ban, DFC has not yet built up robust nuclear energy expertise within the agency, and this lack of technical knowledge and experience with nuclear energy presents a barrier to more robust engagement in nuclear activities. Technical assistance is available to them within the interagency—and last year the Department of Energy detailed a staff member to DFC for nuclear-specific technical support—but decision-making would be smoother with more in-house expertise. Congress should direct DFC to increase the nuclear expertise among its staff.

- Increase contingent liability cap to $250B and single project limit to at least $5B: The current contingent liability cap of $60 billion and single project limit of $1 billion make it challenging for DFC to support large nuclear projects. For DFC to prioritize nuclear energy projects for national security and global economic competitiveness, the total cap must be significantly increased, and DFC should remove its self-imposed $1B single project limit, increasing it to the statutory limit of five percent of the total cap.1 Since DFC generates revenue through lending, this new ceiling would not increase costs. Senators Coons and Cornyn already proposed a cap of $100B, but a more ambitious cap (i.e., $250B) would allow DFC to participate in larger nuclear projects up to $12.5B.

- Fix the equity scoring issue: DFC’s equity investments are scored as losses, discouraging DFC from using its equity tool, particularly for large projects such as nuclear. This scoring approach devalues the potential impacts of future profits, disregards the underlying value of the asset, and overlooks DFC’s overall financial impact, as it is actually a revenue creator for the federal government.2 There are several ways to fix this issue, such as establishing a revolving fund or applying net present value scoring to these projects,3 but solutions must focus on encouraging DFC to participate in larger infrastructure projects where its tools are most helpful.

- Create a specific grant window for nuclear feasibility projects: Early-stage feasibility assessments are important parts of nuclear financing decision-making and are effective ways to begin building relationships with customer countries early. DFC has the authority to pursue nuclear technical assistance grants, but has not yet done so, so additional specifications and resources for this activity could encourage more activity in this area.4

The US Trade and Development Agency

While not an export credit agency or lender, the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) is a crucial part of the export financing spearhead, helping countries of interest to US vendors conduct capital-intensive early feasibility and readiness activities for nuclear energy deployment. USTDA is statutorily directed to operate in developing and middle-income countries, which can limit its ability to support nuclear projects in markets more financially ready to deploy nuclear. Despite this, it has still been able to punch above its weight on nuclear projects.

USTDA’s value for nuclear lies in advancing US vendor projects in key markets of interest. Well before a country is ready to finance a US reactor, it must conduct activities like front-end engineering and design (FEED) studies to assess the feasibility of a project. USTDA supports this process by funding these activities and connecting US nuclear businesses with interested markets. Not only does this help establish enduring relationships between vendors and customers, it also gives the US a competitive foothold in that country before adversaries can make headway. For example, USTDA was instrumental in advancing Poland’s and Romania’s efforts to develop nuclear projects based on US reactor technologies.

USTDA Recommendations

- Increase high-income country flexibility for projects that are national security priorities: By statute, USTDA is directed to work in lower income countries. This limited flexibility has prevented it from being able to continue additional phases of its European projects when the World Bank adjusts countries’ income categorizations. Congress could use the model from the European Energy Security and Diversification Act, which exempted DFC from such restrictions for high-priority energy projects, to increase USTDA’s flexibility in higher-income country operations for national security-critical energy projects.

- Expand USTDA’s capacity to support nuclear projects: USTDA already “punches up” with its limited resources. It could do even more with additional support. Nuclear activity can be cost-intensive, and increased USTDA involvement in nuclear should not threaten USTDA’s capacity to engage in other activities. Therefore, Congress should provide additional resources to USTDA specifically for nuclear activities to ensure USTDA can still carry out its missions in other sectors.

Other Pieces of the Nuclear Exports Puzzle

Financing improvements are key to unlocking the global nuclear export market, but there are other key agencies that must exercise greater coordination to better support this enterprise, including the Departments of Commerce, Energy, and State, as well as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Other countries are eager to partner with the US government on nuclear energy deployment, and robust interagency coordination can spread US safety, security, and nonproliferation standards while improving the attractiveness of US products compared to competitors. Some specific improvements to create a more cohesive, efficient, and timely US nuclear export system and better compete with adversaries’ “one-stop-shops” are:

- Create and authorize a line item for the Department of State’s Foundational Infrastructure for Responsible Use of Small Modular Reactor Technology (FIRST) Program to enable capacity for growing participation requests; the International Nuclear Energy Act (INEA) of 2025, introduced in May 2025, could be one vehicle to accomplish this.

- Provide additional appropriations for the Department of Energy Office of Nuclear Energy’s international engagement activities, including the establishment of regional nuclear energy training centers and hubs.

- Allocate more resources to the NRC’s early regulatory engagement in emerging markets of interest to both US industry and our geopolitical adversaries.

- Establish a central coordinating role for nuclear exports in the White House or the Trade Promotion Coordinating Committee to align the interagency process and better compete with Russia and China; again, the recently introduced INEA could facilitate policy steps towards this objective.

Conclusion

The US already has multiple export financing tools at its disposal. These tools are designed to work in coordination to offer a start-to-finish financing package that can level the playing field. But right now, these tools are not as strong as they could be. To effectively compete in the global nuclear market, we need to give agencies the resources, flexibility, and authority to successfully support US nuclear exports. That includes continuing EXIM’s and DFC’s Congressional mandates, while using these opportunities to strengthen their resources, authorities, and capabilities. At the same time, Congress can strengthen the rest of the export ecosystem, particularly USTDA. This is a key moment for US national security and global economic leadership. American nuclear is ready to be deployed around the world, but without the financing help to do so, we’re leaving deals on the table and ceding ground to Russia and China.