Memo Published July 12, 2022 · 5 minute read

Third Way National Security Team Launches US-China Advisory Board Search

Recruiting for the Initiative’s Advisory Board

To help ensure the Digital World Order Initiative’s work will be as bipartisan, relevant, and actionable as possible, we are seeking to stand up an Advisory Board. This board would help the initiative explore and develop partnerships, collaborators, and funding opportunities for the program to identify, stop, and punish China’s creeping digital authoritarianism. It would leverage contacts in the private sector, academia, and foundations to help guide solutions tailored for legislation in collaboration with organizational partners and members of Congress. This board would mirror the successes and model of Third Way’s Cyber Enforcement Initiative Advisory Board.

Each Board Advisor must be available for a minimum of three hours a month for the 1-year Advisory Board appointment. Each Advisor will be required to:

- Provide individual advising as needed on securing strategic partnerships, funding and projects

- Be prepared for all advisory board meetings on the US-China Digital World Order program. As such, each Advisor must participate in four 60-minute quarterly board meetings

- Review and be familiar with all materials and content including program materials, presentations, outlines, videos, website links, etc., provided by the Third Way National Security Team

More About the Digital World Order Initiative: What is at Stake

On June 21st, Third Way’s national security team launched the US-China Digital World Order Initiative. A bipartisan initiative which underscores that a new and decisive divide pits America’s approach of “digital democracy” against China’s approach of “digital autocracy"—and the US needs to catch up. Members of the private sector, civil society, and government were in attendance, and the event followed up Third Way’s introductory memo for the Digital World Order Initiative.

China is executing a detailed plan to become the world’s digital superpower. The US is not. As part of the state-driven “China Standards 2035” Project, the Chinese state intends to change the global digital order by redrawing technological norms and standards to outcompete the United States and dominate the free world with its authoritarian model for exportation.1 The outcome of this US-China competition will define the 21st century and have massive implications on US economic, geopolitical, and military strength.

China’s model will enable an information dark age across autocratic nations where whole societies live in a completely distorted version of the world. Current trends point to a stark divide between democratic countries with freedom of speech and press, and authoritarian states with sophisticated disinformation and censorship regimes. Through technologies like the Great Firewall, 1.4 billion people in China alone have already been systematically shunted into state-controlled narratives for understanding the world.2 China is perfecting its technology-enhanced authoritarianism for export, and dictators like Vladimir Putin are signing up to better hide horrific truths from their citizens.3

As reported in NextGov, : “I think creating more inclusive and democratic processes that bring in emerging countries who will have incredible innovation over the coming decades and be the users and deployers of so much of this emerging technology is also really important,” Berry said, noting a 60-nation declaration the White House led in April on the future of the internet.

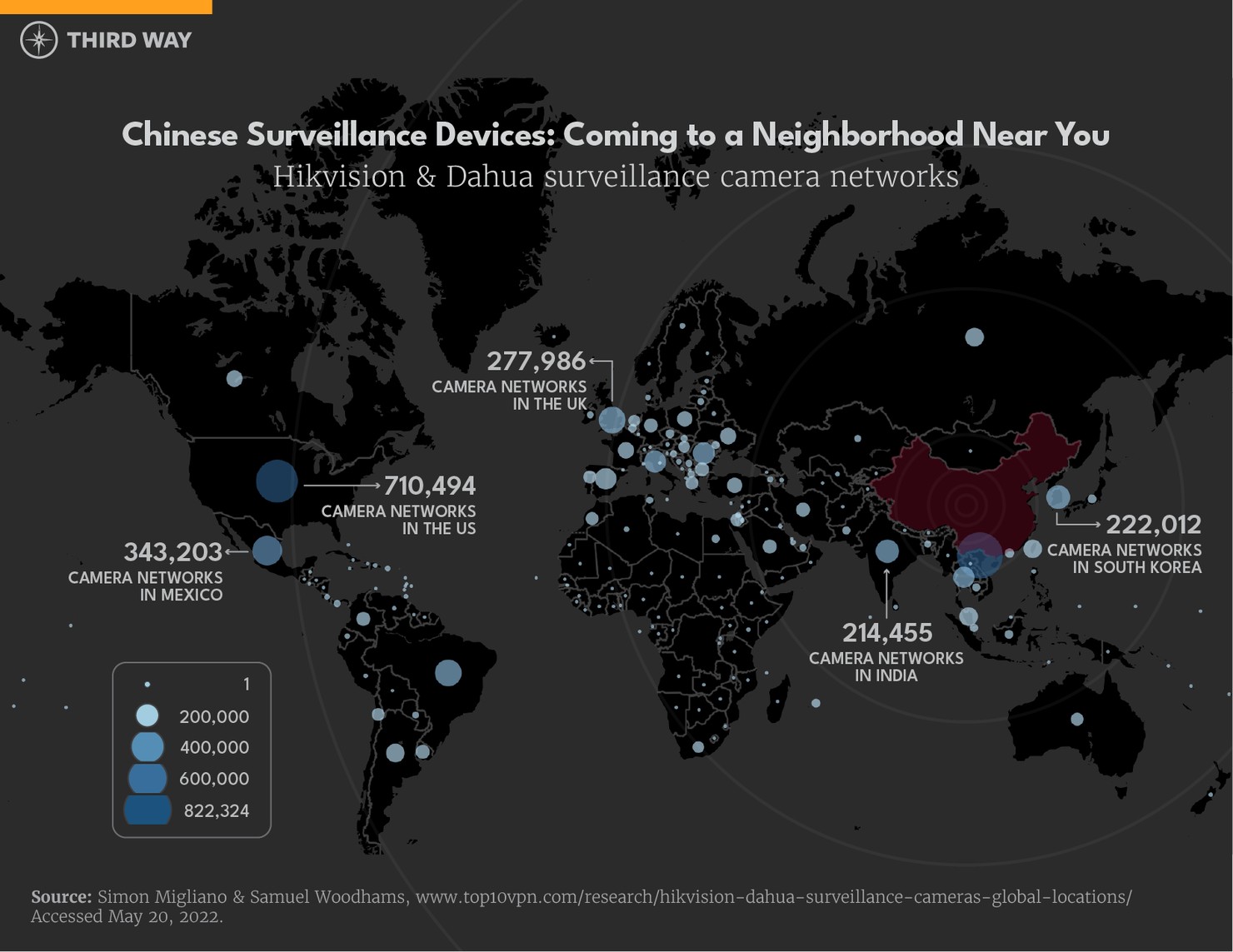

China’s digital police state uses mass surveillance technologies and big data to restrain basic freedoms and liberties. Chinese state officials can track its citizens through voice recognizing-social media monitoring, artificial intelligence and facial recognition-enhanced security cameras, and Internet-enhanced neighbor snitching.4 This surveillance data is compiled into social credit scores and advanced algorithms to curtail the freedoms of dissidents and “deviants”—including blocking travel for civil rights lawyers, detaining ethnic and religious minority Uyghurs for praying, and punishing journalists for “spreading rumors.”5

The Chinese government also conducts operations to serve their economic and geopolitical interests by spreading and strengthening Chinese technological authoritarianism.

- Exporting telecommunications equipment: China made a billion-dollar market for establishing global digital infrastructure, while also using that same infrastructure to stifle overseas dissent and give similar tools of repression to their allies.6

- Stealing American intellectual property: China has been able to supercharge their own tech economy and claim the Chinese state spurs innovation.7

- Banning cryptocurrency and promoting the digital yuan: China has dismissed decentralized economic power, and instead doubled down on their efforts to make yuan-transactions yet another means of global surveillance, as well as empower the yuan to be a global currency rivaling the US dollar in influence.8

- Hacking into foreign governments: China degrades the security of democracies through extensive cyberespionage operations. The collected data is used for further political and intelligence operations which target enemies of the Chinese government.9

The US government is recognizing the national security threat of China’s technological aspirations and cyber operations. In March 2021, the FCC recognized the risks of China’s digital control and designated several Chinese telecommunications firms, including Huawei, as national security threats to US government vendors and are restricted from conducting business with.10The annual Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s threat assessment noted, “China presents the broadest, most active, and persistent cyber espionage threat to U.S. Government and private sector networks” and the Chinese government “will work to undercut U.S. influence, drive wedges between Washington and its partners, and foster some norms that favor its authoritarian system.”11

China’s military buildup strategy also relies on gaining and maintaining the upper-hand in the digital global order. In addition to a traditional military arms race, Xi Jinping has recognized the importance of integrating digital superiority in China’s armed forces. Xi has called for a highly “informatized” military capable of dominating all networks, and to establish next-generation “intelligentized” warfare capabilities using advanced technologies like AI and quantum computing.12