Report Published July 24, 2024 · 8 minute read

What the Far Right Gets Wrong about Medicaid

David Kendall

Takeaways

Medicaid is a foundation for work in the United States, not a welfare program as some ideologues see it. Far right proposals proposals to turn Medicaid into a block grant or cut coverage for the working poor ignore three key facts about people with Medicaid coverage:

- People with Medicaid coverage work despite having more health problems than others.

- Workers with Medicaid who are unemployed struggle with daily activities and decisions.

- People with Medicaid coverage who do not work have more than their fair share of health problems.

The far right sees Medicaid as a welfare program, and they continue to push for penalties against Medicaid enrollees without a job. The problem is that the view of Medicaid as welfare is divorced from reality. Most people with Medicaid coverage who can work do work.1 Medicaid is often their only source of affordable coverage because many employers do not provide health insurance. Those who are out of work often have health-related obstacles. And those who cannot work need Medicaid because they do not have any other source of coverage.

Setting the record straight on Medicaid is important because Republicans may come after it. The Republican Study Group, which includes most House Republicans, singled out Medicaid with a proposal to end the guarantee of coverage for enrollees.2 In one fell swoop, they would cut coverage for “able-bodied adults” who are poor and cut Medicaid’s coverage guarantees for other vulnerable groups under a proposal known as a block grant. Former President Trump used the same approach to push for $880 billion in budget cuts to Medicaid along with penalties for Medicaid enrollees without a job.3 The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 proposes to halt an individual’s Medicaid coverage at an arbitrary point in their life.4 That’s on top of Republicans in 10 states who continue to hold up expansion of Medicaid to the working poor.

People with Medicaid coverage deserve better. Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which is the nation’s largest health survey, shows why:

- People with Medicaid coverage work despite having more health problems than others.

- Workers with Medicaid who are unemployed struggle with daily activities and decisions.

- People with Medicaid coverage who do not work have more than their fair share of health problems.

In this report, we provide a brief overview of Medicaid coverage, a comparison of health problems for workers with and without Medicaid, and state-level data.

How Medicaid Supports Workers

Ironically, it was a Republican-controlled Congress in 1996 that turned Medicaid into a program to support work. Previously, most adults had to be on welfare to qualify for Medicaid. Under the welfare reform legislation that the Republican Congress passed and President Clinton signed into law, Medicaid became a program to support people as they got a job. Poor adults could have health care coverage through Medicaid even if their employer did not provide it.

Such coverage for working poor adults has been critical since employer-sponsored coverage misses 76% of low-income workers (with incomes under twice the federal poverty level).5 They tend to work at a low wage for employers that don’t provide coverage. The purpose of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to fill the gap for low-income adults. Forty states and Washington, DC have adopted the Medicaid coverage expansion.6 Research has shown that Medicaid expansion has not substantially reduced the number of adults choosing to work.7

Medicaid also provides a backstop for veterans. It covers 9.4% of all veterans, including many who have no other source of coverage.8 That’s because some veterans do not qualify for VA care, live far from VA facilities, or cannot get coverage through a job because their employer does not offer it.

Medicaid supports people who have challenges working as well. These groups include people who are blind, deaf, or have other disabilities. Medicaid expansion has increased work among people with disabilities.9 Prior to the ACA, they could not earn much money without losing their Medicaid coverage. Medicaid expansion lets them qualify for Medicaid with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, and the ACA marketplace provides them coverage if they earn more than that.

The largest demographic enrolled in Medicaid and in its companion program for children (the Children’s Health Insurance Program) are white (43%) followed by Hispanic (28%), Black (21%), Asian/Pacific Islander (5.5%), and American Indian and Alaska Native (1.3%).10

Lastly, Medicaid provides long-term care to older Americans who cannot care for themselves because of disability or old age as well as coverage for low-income seniors that supplements Medicare. Overall, Medicaid is a lifeline for 84 million people. It serves more Americans than Medicare.

People with Medicaid work despite having worse health problems.

Adults with Medicaid coverage who are working have worse health and miss work more often because of their health. Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the nation’s largest health survey, shows:

- 20% of workers with Medicaid feel fair or poor compared to 11% of all other workers.11

- 16% of workers with Medicaid lose 10 or more days of work or other usual activities each month because of physical health problems compared to 9% of other workers.

- 29% of working adults on Medicaid lose 10 or more days of work or other usual activities due to mental health problems, compared to 18% of other workers.

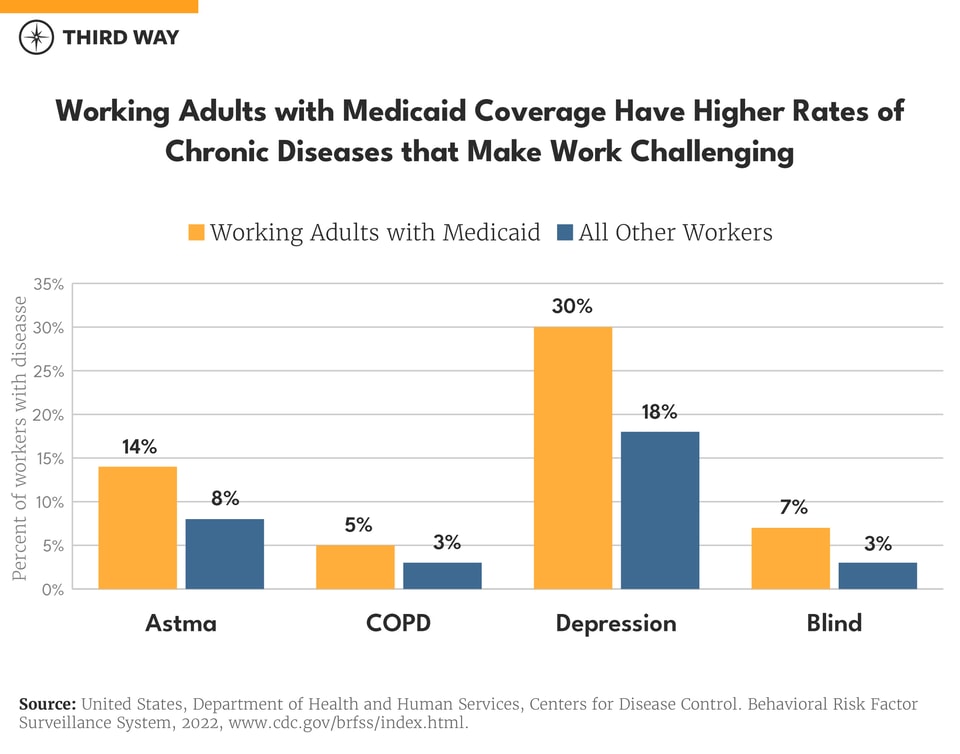

Medicaid beneficiaries typically have more challenging health issues, which explains why they lose more workdays than other workers. Working adults with Medicaid have higher rates of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depression, and blindness as shown in chart below—all of which can significantly interfere with working.

For other health problems—like heart disease, diabetes, and kidney disease—working adults with Medicaid coverage have similar rates compared to other workers. The rates of health problems for people with Medicaid, however, vary significantly by state, as shown in the spreadsheet available here.

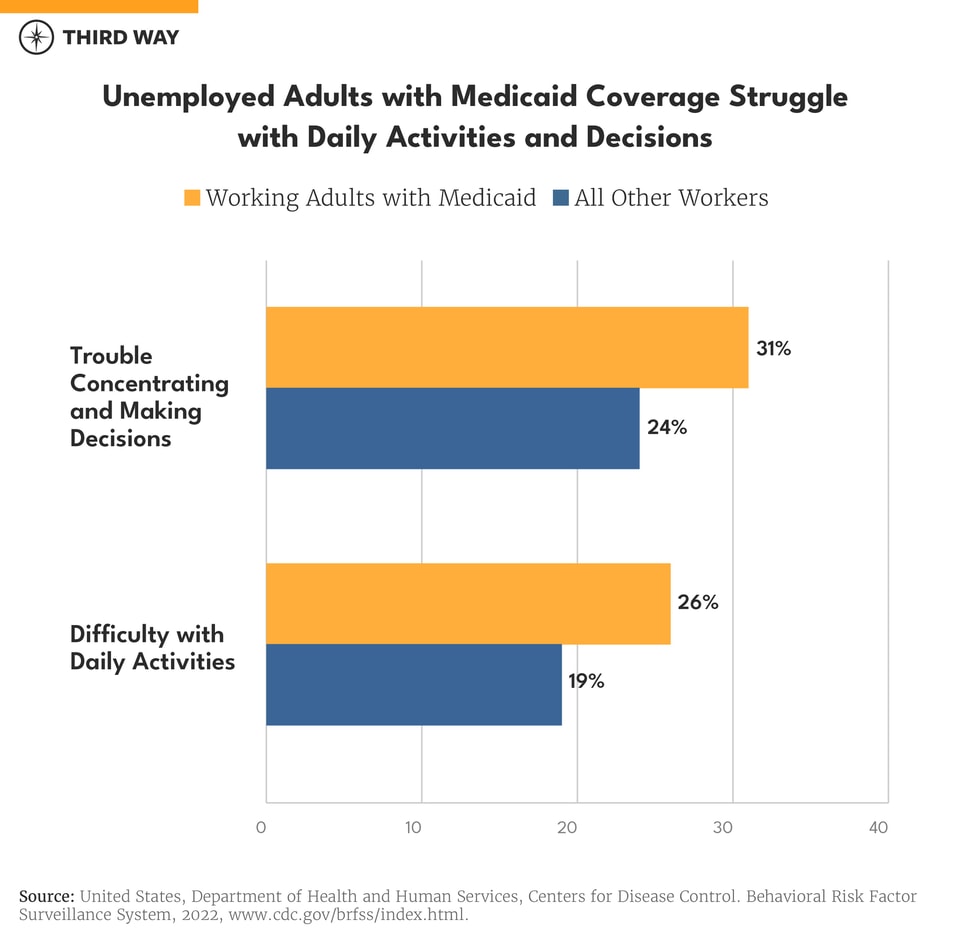

People with Medicaid who are unemployed struggle with daily activities and decisions.

In general, workers who are unemployed have more health problems—regardless of the coverage they have. Unemployed workers with Medicaid, however, have more challenges, which may prevent them from getting work. They are more likely to have trouble with everyday activities like climbing stairs and more often have trouble concentrating or making decisions because of a health problem. As shown in the chart below, 26% have trouble with everyday activities compared to 19% for other unemployed workers, and 31% have trouble concentrating or making decisions as opposed to 24% of other unemployed workers.

Unemployed workers also have higher rates of fair or poor health, chronic diseases, and days lost to poor health. The data appendix includes those specific rates.

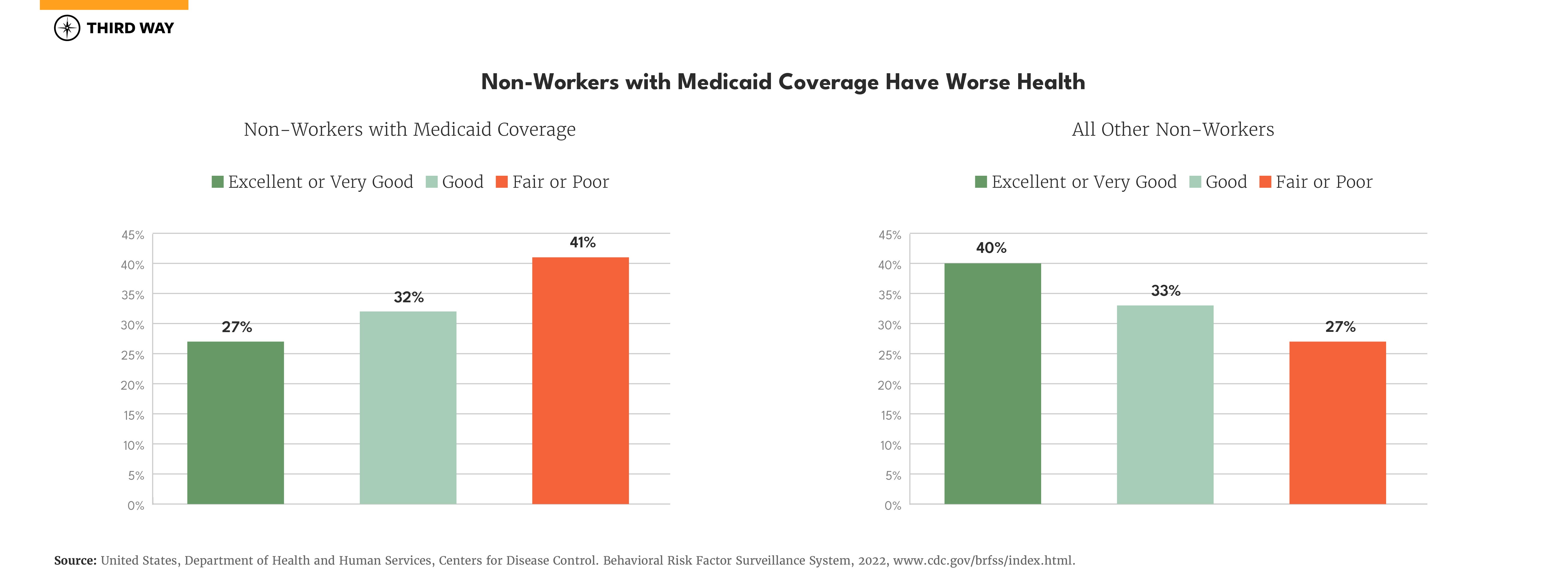

Adults with Medicaid who do not work have worse health.

Adults with Medicaid coverage who are not working because of disability, family responsibilities, going to school, or any other reason, have health problems at much higher rates than others. Four-in-ten say their health is fair or poor. That is compared to three-in-ten for all other non-workers and two-in-ten for the whole adult population. The breakdown for each health status is shown below.

Other measures also indicate poorer health for non-workers with Medicaid coverage especially for mental health:

- 38% struggle with depression compared to 22% for others.

- 43% can’t do their normal activities 10 or more days each month compared to 30% for all other non-workers.

- 19% have asthma compared to 11% for other non-workers.

- 32% have trouble concentrating or making decisions compared to 16% of others.

Conclusion

Adults with Medicaid need coverage as much if not more than others due to challenging health issues. They need coverage to go to work and lead their lives. That’s why far-right proposals for Medicaid make no sense. Threatening adults with the loss of health care coverage is not going to make them more likely to work. Instead, it will reduce the access to care they need to work.12 Ending Medicaid’s guarantee of coverage through a block grant proposal threatens everyone with Medicaid coverage, regardless of employment status.

All forms of health care coverage in our nation have guaranteed financing for each individual who qualifies. Federal law guarantees tax benefits for employer-sponsored coverage, which reduces the cost of coverage by as much as half, or more, depending on the employee’s tax bracket. The Affordable Care Act guarantees financing on a sliding income scale for people whose employer does not provide it. Medicare offers a guaranteed coverage for older and disabled Americans. Radical change by converting it into block grant would threaten and possibly eliminate that guarantee. A Republican work requirement would impose significant bureaucratic hurdles and make Medicaid coverage unlike anything else in our health care system.

Medicaid is a critical foundation for work in the United States.

Medicaid is a critical foundation for work in the United States. Most people with Medicaid coverage who can work do work. Taking it away will not help those who need health care. Rather, it would it harder for them to work and make our nation less productive.

Methodology

The data in this report is from the 2022 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.13 It is a collection of state-administered surveys of adults 18 years and older, using a base format designed by the Centers for Disease Control. We separated the data into two groups: those reporting Medicaid as their primary form of coverage and all others. We then selected relevant health indicators to compare the health status of the two groups. Lastly, we defined work status using three categories: currently working (for wages or self-employed), unemployed for less than a year or more than a year, and not a worker, which includes students, homemakers, retirees, and those unable to work. The data for this report along with state level data can be downloaded here.