Report Published July 13, 2020 · 12 minute read

Throwing Out the “Recession Playbook” for Higher Education: The Need for Joint Federal-State Policy in the Wake of COVID-19

William R. Doyle

The Upshot

During any recession, federal and state policymakers and college leaders need to make hard choices about how to allocate resources to keep institutions running. Higher education’s response at the state and institutional levels to past economic downturns has drifted into a playbook of sorts.1 State legislators cut higher education’s budget more than other state spending categories, and in response college leaders raise tuition. While these strategies have allowed states and college systems to limp through past downturns, it’s very likely that this approach will not work in the coming recession. Instead, federal intervention will be needed in the wake of COVID-19 to avoid rapidly increasing college prices and decreasing enrollment.

The current recession will be different—and worse for higher education—than past recessions. States are likely to experience substantial increases in demands for both health care and public assistance, while simultaneously experiencing precipitous declines in tax revenues. Colleges and universities will likely have less demand, resulting in shortfalls in both enrollment and tuition revenue and increasing the pressure to raise tuition and cut financial aid. A joint federal-state program can provide funding that will allow students to attend college, while simultaneously stabilizing revenues for institutions of higher education. The key to this program will be focusing on one goal: college affordability for as many students and families as possible.

Narrative

The State Higher Ed Recession Playbook

State policymakers face a daunting set of tradeoffs during a recession. Unlike the federal government, almost all states must balance their budgets, requiring expenditures to equal revenues.2 As revenues plummet due to lower income or sales taxes (or both in some states), expenditures must simultaneously be cut. At the same time, demand for state services increases, particularly in areas such as health and public assistance—in the wake of COVID-19, it’s quite likely that demands in both of these areas will be even higher. That’s why when state policymakers must make cuts somewhere, they often turn first to higher education.3

Higher education is unique among state budget categories in that it has a substantial alternative revenue source: tuition. Unlike Medicaid, K-12 education, or transportation, higher education has historically been able to quickly increase its revenue by raising tuition. This makes colleges and universities a target for large budget cuts during downturns.4

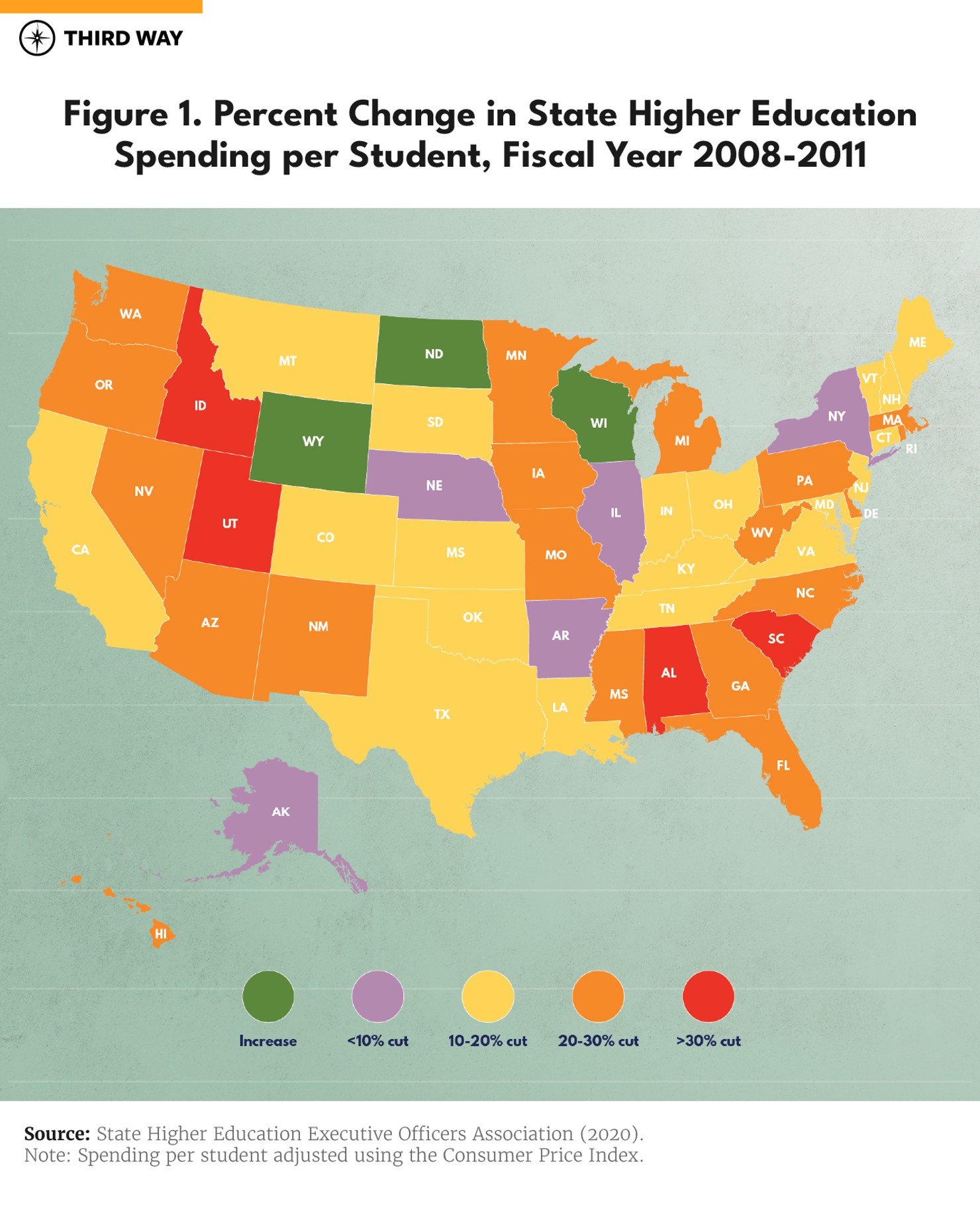

The “playbook” that state policymakers and institutional leaders have adhered to in past recessions goes like this. Typically, state policymakers will decrease appropriations for higher education, while at the same time lifting any restrictions on tuition increases. This allows college and university leaders to raise tuition, while at the same time allowing policymakers to disavow any responsibility for these increases.5 In addition to cutting appropriations, state policymakers will many times cut funding for state funded need-based financial aid programs—money that often helps the lowest-income students attend college.6 As a result, higher education tends to face larger budget cuts than other state spending areas overall, and in response, colleges and universities raise tuition and cut institutional financial aid budgets. Between fiscal year 2008 and 2011, state spending for higher education on a per-student basis fell by about $1,600, an average decline of 18% across the states. Spending per student dropped in 48 states, with cuts of over 30% in Alabama, South Carolina, and Idaho.7

Tuition increases and financial aid cuts come at the worst possible time for students and families. Just when incomes are declining and a larger proportion of the population is unemployed, they are asked to pay more to attend college. During the Great Recession, in-state tuition at public four-year institutions increased in all 50 states by an average of $1,300. Tuition increases at these institutions across the states averaged about 27% during this time period.8 As a result of tuition increases like these, many students and families, particularly the lowest income students who stand to benefit the most from going to college, find themselves priced out of college and unable to attend.

Still, colleges and universities were in a position to raise tuition during past recessions because of a large amount of excess demand for higher education. The payoff to attending college has only increased in the last thirty years, and many analysts agree that, in fact, too few people have been attending and graduating from college given the high level of demand for highly-educated individuals in the labor market.9 Research has confirmed that for every additional year of postsecondary education, earnings are predicted to increase by about 8%.10 And while more students have graduated from high school and demonstrated college-readiness, states have not gotten close to achieving their stated goals for postsecondary attainment. In Tennessee, for example, the goal is for 55% of the adult population to have a postsecondary credential, but only 43% of the population has this level of attainment.11

At every level of higher education, from elite universities to open-access community colleges, there have been more people who want to go than can afford to go. With this kind of excess demand, many colleges and universities have been able to raise tuition and be confident that enough students—mostly middle- and high-income students—would find a way to pay the bill. And what many students did to pay the bill was to borrow the money, resulting in a massive expansion of student debt. Total student debt exceeds $1.6 trillion and is now the largest source of consumer debt, exceeding the total amount of money owed for credit cards or auto loans.12

Why this Recession is Different

The coming economic downturn is different from the previous ones, and the past “recession playbook” won’t work to address the new challenges it poses. For one, colleges and universities are very unlikely to have the same kind of excess demand that they have benefited from in the past. Partially in response to unstable state funding, many public colleges have come to rely on the most lucrative sources of tuition revenue, including out-of-state students and foreign students, both of whom pay considerably higher tuition than in-state students.13 Restrictions on travel from other countries and an unwillingness to pay higher prices will likely mean that colleges cannot rely on these alternative sources of tuition revenue. Specific to the current crisis, colleges in many states may be unable to offer in-person instruction due to the ongoing spread of COVID-19, and it’s likely that many students may be unwilling to pay for or attend college in an all-online setting, further decreasing enrollments and tuition revenue. Beyond a reduction in demand, family budgets will be strained to the breaking point due to job loss and reduced pay, and so many families may simply be unable to pay for college even at current prices, let alone the higher prices that colleges have charged in past recessions.

In past downturns, college and universities have also relied on an increase in attendance as more individuals are out of the labor market. This well-documented bump in enrollment during recessions occurs because recent high school graduates who are unable to find work are likely to choose to go to college instead, and older workers who find themselves unemployed return to higher education for retraining or new skills. During the Great Recession, this increase in enrollment for public colleges was smaller than expected, and during the coming recession, there is every reason to think that both recent high school graduates and recently unemployed workers will be unwilling or unable to take on the large amount of debt that would be required to attend higher education if prices increase as they have in the past.14 Prior study of the impact of the Great Recession on higher education has found that “While nonprofit four-year institutions, including research universities and liberal arts colleges, accounted for nearly 20% of postsecondary enrollment in 2007, these institutions absorbed about only 10% of the students induced to enroll with the Great Recession.”15 Relying on student debt as the funding source of last resort is likely no longer an option, as students and families will face far more uncertainty about the labor market than they have in the past, and research suggests that as uncertainty in labor market outcomes increases, students should be generally less likely to borrow to finance their education.16

Critically, higher education also finds itself entering this new recession without having fully recovered from the last. Past recessions have ended after a few years, and policymakers in most states increased funding for higher education as state revenues increased. In the 1980s, nearly all states that experienced a cut of 5% or more in higher education returned to their previous levels within 10 years. In the 2000s, only 25% of states recovered to their previous levels after cuts of 5%, and between 2010 and 2018, only three states had recovered to their previous levels after a cut of 5% or more.17

Policy Implications

Federal and state policymakers and institutional leaders must agree that the needs of students and families will be the first priority in discussions about higher education funding. To do this, college leaders and state policymakers must commit to certain levels of either tuition or financial aid—or both. At a bare minimum, state policymakers and institutional leaders should commit to no increases in tuition at public colleges and no cuts in need-based financial aid in the coming 2020-21 academic year, conditional on the federal government providing needed assistance.

For years, there have been widespread calls for state-federal solutions to the problem of college affordability.18 The time to create this state and federal partnership is now. States are constrained by balanced budget requirements and will not be in a position to provide sufficient funding for institutions of higher education given the demands on other spending categories. State rainy day funds will be insufficient to weather the recession. Tuition will go up, and attendance will go down. In a time of significant financial turbulence, the federal government can step in and provide funding to ensure that students can afford to attend college. State policymakers, along with institutional leaders, should join together to call on the federal government for a joint federal-state partnership for higher education.

In beginning the conversation about what this partnership should look like, federal and state policymakers should consider a range of ideas designed to support both postsecondary student access and success and long-term financial sustainability for institutions, such as:

Federal match for state financial aid spending. A joint federal-state program that commits the federal government to matching state spending on need-based financial aid on a 5-to-1 ratio is a good place to start the conversation. Supporting need-based aid (which can be broadly defined) provides funding for students who have the highest need and is the most efficient way to encourage college enrollment. Low-income students are the most responsive to changes in price, so lowering the price for them creates larger changes in college access. As opposed to directing funding to institutions, a matching program avoids many of the problems of federal programs supplanting instead of supplementing state programs. As states spend more on something they should be doing anyway, they receive increased funding from the federal government, creating a virtuous cycle.

State commitment to maintaining college affordability. The federal government has every right to design a federal-state program that requires both states and institutions to make needed changes in order to help students and families afford to attend college. This could involve states committing to either maintain certain tuition levels—even free tuition for certain institutional sectors—or certain net prices. Programs that utilize a “matching” strategy can overcome some of the issues that arise with maintenance of effort provisions, which involve mandating certain levels of state funding.

Use the right tool for the job. One key warning to be aware of in designing policy to ensure college affordability is that financial aid programs are very good at one thing, and that’s encouraging college enrollment. Getting students to enroll is an important goal, and it’s worth creating funding to make sure this happens. Using financial aid for other purposes, such as encouraging students to take certain majors or to seek employment in certain fields, doesn’t work. Financial aid is the right tool for one job: getting students into college. Additional policy changes may be required to advance other crucial federal goals, like ensuring that students are able to make it not just to but through college and that schools are actually providing a return on investment to students and taxpayers.

Plan for the long term. A joint federal-state matching program should not be conceived of as a short-term fix, as was the case with the funds provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Instead, it’s time for the states and the federal government to work together to create a joint program that stabilizes support for higher education and avoids the boom and bust pattern of higher education funding that has been the norm over the last few decades.

State officials and institutional leaders can and must learn from past experience and do better to ensure that every student who needs to go to college can afford to attend—and the federal government can and must recognize that it should have a larger role in this new playbook. Unlike prior recessions, ensuring that students and families can afford to pursue higher education should be the first priority, not an afterthought.

Methodology

Along with my colleague Jennifer Delaney, I have analyzed patterns in state spending for higher education compared with other state expenditures as a function of the business cycle and the characteristics of states. We used a comprehensive dataset of all 50 states going back nearly 40 years to document patterns in state funding over time, with a particular focus on how cuts during recessions are related to increases during economic recoveries.