Report Published October 17, 2014 · Updated October 17, 2014 · 23 minute read

Q&A on International Corporate Tax Reform

David Brown

Takeaways

Three recent major reform proposals —those of Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI), former Chairman (now Ambassador) Max Baucus (D-MT), and President Barack Obama—attempt to solve the same three major problems:

- America’s OECD-highest tax rate is driving companies to relocate abroad;

- The “lockout effect” leads companies to keep profits overseas; and

- Cracks in the international system encourage multinationals to locate profits in countries with low or no corporate tax.

These central problems present a major opportunity for a bipartisan reform that, once enacted, would provide a significant boost to the U.S. economy.

Why Does the International Corporate Tax System Matter?

The international corporate tax system can seem like an obscure, arcane section of the revenue code. And the taxes flowing to the IRS from foreign-earned corporate profits are only a trickle. In 2012, the IRS collected $2.5 trillion in total revenue. Only $242 billion (10%) came from corporate taxes altogether.1 And a smaller segment still came from taxes on corporate foreign-earned profits.

But the laws affecting the taxation of international corporate profits are very important, not just to the companies subject to them, but also to the broader U.S. economy. Here’s why:

- First, tax laws vary from country to country, and these differences influence the location of global business activity: where companies locate their profits, where they locate their headquarters, where they locate their R&D, and where they locate production.

- Second, a multinational corporation’s home-country tax laws on foreign profits can help or hinder its success in foreign markets.

- Third, the international side of the corporate code affects the domestic corporate tax base and, as a result, the revenue it generates. When an international tax law contributes to a U.S. corporation’s decision to move its headquarters abroad, for example, that eliminates U.S. jobs and weakens the domestic tax base.

Today’s globalized economy raises the significance of all three of these dynamics. The last time Congress rewrote its corporate tax code, in 1986, America was far and away the dominant world economic power. U.S. companies selling in foreign markets simply faced fewer and less competitive foreign rivals.

In 1990, one third of Fortune Global 500 businesses were headquartered in the United States. Another quarter was based in Japan, which had an international tax code similar to America’s. Today, U.S. companies make up only one fourth of the Global 500, and the remainder no longer hails primarily from rich-country allies; rather, a wide range of emerging markets are well represented.2

Furthermore, two factors increase the importance of business conducted by U.S. companies abroad. First, because most of the world’s economic growth is located overseas, American companies must tap that growth in order to grow. Second, supply chains are more mobile today than in the 1980s. The free-flow of information and the rising prevalence of high-tech goods and services mean more commerce involves lightweight or weight-free intangible products. That reduces transportation costs and allows production to move more freely about the globe. So not only does the international corporate tax system matter greatly, it also matters now more than ever before.

What Are the Basic Elements of Our International Tax System?

Five key provisions characterize our international tax system: our tax base, statutory rate, worldwide taxation, the Foreign Tax Credit, and deferral. These elements are critical to the effectiveness of the international code and the ability of U.S. companies to compete against companies based overseas.

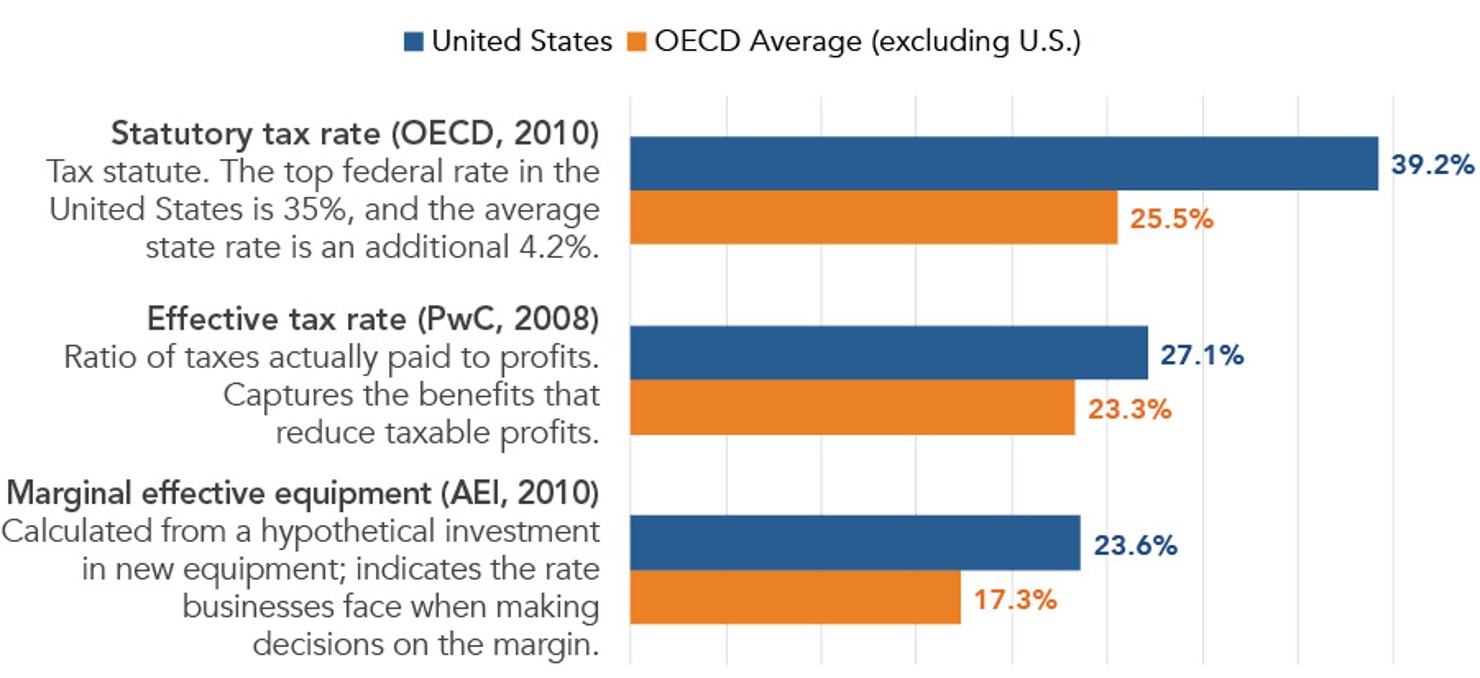

Most fundamental to how the U.S. international corporate tax system works are two features not particular to the international section of the code at all: a narrow tax base and a high statutory rate of 35% (including the average state-level corporate tax rates, the total statutory rate is 39.2%).3 These features combine to give the United States a highly distortive corporate tax system.

Consider a fictitious, but representative example: AverageCo USA. When AverageCo USA prepares its taxes, the many available tax breaks allow the company to sizably reduce its taxable profits. Say AverageCo USA makes $1 billion in pretax profits for 2013. Because of a litany of deductions and other preferences, AverageCo USA is able to reduce its taxable profits from $1 billion to $691 million. Then, that $691 million is taxed at a combined 39.2% rate, resulting in a tax bill of $271 million. AverageCo USA, therefore, has an effective tax rate of 27.1% ($271 million in taxes from $1 billion in profits). That was the average effective tax rate (ETR) for U.S. corporations in 2012, according to one major report.4 Studies differ on how ETRs in competing countries compare. At best, they are roughly the same. More likely, other countries have ETRs that are significantly lower, around 19.5% by one estimate.5

Comparing tax rates: United States and the OECD

Congressional Research Service (Gravelle, 2014)

It’s harmful enough that U.S. companies likely face higher-than-average ETRs; the high marginal tax rate, though, creates additional problems. At 39.2%, the combined marginal rate is nearly 10 points higher than the average marginal rate of U.S. competitors (29.6%). The key point is that an incremental dollar of profits in the United States will be taxed at 39.2%. This marginal tax rate impacts investment decisions. If AverageCo were to make an investment to allow it to perform more efficiently, boosting sales or reducing costs to gain an additional $10 million in profits, its shareholders would keep only $6.08 million (assuming that the additional profit would not to generate additional deductions and credits). That’s not as powerful an incentive to improve efficiency on the margins as a system with no tax preferences and lower rate of, for example, 27%. It also means that AverageCo is incentivized to look toward the tax code to boost its after-tax profits.

The code’s numerous tax breaks and high statutory rate are critical to how the international corporate system works. Two other key elements of our system are worldwide taxation and the Foreign Tax Credit. Having a worldwide system means that AverageCo USA pays taxes not only on its profits from U.S.-based operations, but also on the dividends it receives from its overseas subsidiaries. (Corporations, like individuals, can hold stock of other companies. And they earn profits from their overseas subsidiaries by collecting stock dividends from these companies.) By contrast, countries with territorial systems primarily tax income earned within their borders.

Here’s how worldwide taxation works: Say AverageCo USA is the sole shareholder of AverageCo Ireland, which earns $10 million in annual profits. Ireland has a 12.5% statutory corporate rate. Assuming no deductions, AverageCo Ireland pays $1.25 million to the Irish government. Then, if the U.S. parent company decides to repatriate the remaining profits back to the United States as a dividend ($8.75 million), the worldwide system means that the dividend is subject to the U.S. corporate tax.

But if the entire dividend were taxed at 39.2%, that would be double taxation: AverageCo USA would be paying U.S. tax on profits already taxed by Ireland. That’s where the Foreign Tax Credit comes in. The Foreign Tax Credit essentially says AverageCo USA must only pay tax on its dividend to cover the difference between Ireland’s and the United States’ corporate tax rates. So because Ireland taxed the profits earned in Ireland at 12.5%, the United States taxes the repatriated profits at 22.5% (35%-12.5%).* AverageCo USA pays $2.25 million in tax to the IRS (again, assuming no deductions), bringing the total tax rate on the repatriated Irish profits to 35%. The reason why the high U.S. rate is important is that if the Irish rate were higher than or equal to the U.S. rate, dividends paid by AverageCo Ireland to AverageCo USA would be tax free in the United States.

States’ tax treatment of repatriated dividends varies.

It is important to note that many of the United States’ international tax rules apply primarily to companies incorporated in the United States.* Companies incorporated abroad are subject to their home country’s international tax rules. Differences in international tax rules among countries can create competitive advantages or disadvantages among companies competing in the global marketplace.

Some foreign companies that own U.S. firms or large stakes in U.S. firms are subject to U.S. international rules.

For example, consider the example above where AverageCo USA pays a total Irish/U.S. tax of $3.5 million ($1.25 million to Ireland plus $2.25 million to the United States). If the exact same activities were undertaken in Ireland by CanadaCo, AverageCo’s Canadanian-incorporated competitor, then the U.S. international tax rules would not apply. Instead, CanadaCo would follow the Canadian international tax rules. Because Canada has a primarily territorial international tax system, CanadaCo would owe no Canadian tax on repatriations of Irish subsidiary’s active income. As a result, CanadaCo would pay only the Irish tax of $1.25 million—much less than the $3.5 million paid by AverageCo USA. Thus, CanadaCo earns a much higher after-tax return on its Irish operations, which gives it a competitive advantage over AverageCo USA.

Deferral is another important element of our international corporate tax system. Deferral means that AverageCo USA generally does not have to pay taxes to the IRS on AverageCo Ireland’s profits until AverageCo USA receives a dividend from AverageCo Ireland—in effect “bringing the money back to the U.S.” Deferral for corporations is comparable to the way an individual shareholder pays taxes on stock dividends: he or she must pay taxes on a corporation’s profits only upon receipt of an actual dividend.

Not all foreign-earned profits are eligible for deferral, and thus, subject to the lockout effect. The “Subpart F” section of the code requires that certain types of foreign-earned income be taxed currently by the United States, whether they are repatriated or not. In particular, certain types of passive income are subject to immediate U.S. taxation. Examples of passive income include royalties, interest, dividends, and other investment income that does not meet the “active test,” whereby a U.S. company is engaged in development, creation, or production.6 These rules, while important, do not guarantee that all overseas passive income is taxed currently by the U.S. Government. In fact, as is explained later, corporations are able to use a number of strategies to protect overseas passive income from U.S. tax.

How is the U.S. System Performing?

By almost any standard, the U.S. international corporate tax system is failing. It evokes distortive business behavior, from high compliance costs to cash held overseas to underinvestment in the U.S. economy.

The primary goal of any tax system is the collection of revenue. The U.S. international corporate system consists of numerous complex rules but generates comparatively small amounts of revenue. The result is tremendous administration and compliance costs. A study by economist Joel Slemrod shows just how inefficient the international corporate tax code is. While only 21% of U.S. companies’ assets and 18% of their employees were located abroad, 39% of their federal tax compliance costs were attributable to foreign activities.7

Furthermore, U.S. corporations’ tax payments to the U.S. Treasury make up as little as 2.3% of their gross foreign earnings.8 That’s in spite of the fact U.S. companies face high overall tax rates. Foreign tax credits, deferral, and base erosion mean that a relatively small share of foreign profits is subject to U.S. tax. The 2.3% figure is an important one to remember for policymakers hesitant about reform because they fear losing tax revenue. For all of the complexities and distortions, the international portion of the corporate code is not a significant source of revenue for the Treasury.

Perhaps low revenue collection could be tolerated if the system’s incentives were generating positive outcomes. After all, some taxes are designed to influence behavior more than to reap revenue. But on the incentive front, the corporate system is failing too.

Democrats and Republicans agree that chief among undesired outcomes is the lockout effect, which exists due to the combination of a high rate, a worldwide system, and deferral. Again, consider AverageCo USA. After earning profits through its Irish subsidiary, AverageCo USA has a major disincentive to collect a dividend from AverageCo Ireland and bring the money back to the United States—a 22.5% tax on top of the 12.5% tax the profits were already subjected to in Ireland. The result is that companies like AverageCo keep much of their foreign-earned profits on the books of their overseas subsidiaries or reinvest those profits in overseas operations. The consequence is that companies have invested more in their overseas subsidiaries and less in the United States. According to J.P. Morgan, the stock of earnings held by U.S. multinationals abroad reached about $1.7 trillion in 2012.9

The lockout effect depends on the presence of all three policies listed above. Without a high statutory rate, U.S. companies wouldn’t owe so much additional tax on repatriated profits, and often they would owe no tax on those profits. Without a worldwide system, repatriated profits simply wouldn’t be subject to tax. And without deferral, companies would have to pay taxes on their overseas profits the year they are earned—whether they are repatriated or not. But solving the problem isn’t as simple as just removing one of the three policies. Simply lowering the rate or moving to territorial costs money, and simply eliminating deferral would make U.S. companies less competitive abroad. Reform must carefully address the lockout effect in a way that both improves U.S. competitiveness and protects the U.S. tax base.

What is Base Erosion and Why is it Happening?

The lockout effect is not the only factor causing corporations to reduce their taxable profits in the United States. Differences between the U.S. international code and those of other countries present opportunities for companies to shift taxable profits. Since America’s last tax code rewrite, its economic peers have developed not only more competitive economies, but also more competitive tax codes. In general, there has been a shift to lower rates, broader tax bases, and more territorial-type international systems. For example, rates have dropped in Ireland (12.5%), Poland (19%), the United Kingdom (21.0%), and Switzerland (21.1%).10 These countries’ changes present valuable lessons for the United States as it pursues its own corporate reform.

Certain countries with even lower corporate tax rates are more infamously known as tax havens. These tend to be small countries—many are islands—which host numerous and extremely well-heeled multinational subsidiaries considering the size of these countries’ economies. Examples include Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and the British Virgin Islands. In many cases, subsidiaries are located in these countries not to conduct business in them, but strictly to benefit from tax laws.

Top Tax Havens for U.S.-Based Multinational Companies11

Country or Jurisdiction | Profits of U.S.-Controlled Corporations |

Bermuda | 645.7 |

Cayman Islands | 546.7 |

British Virgin Islands | 354.7 |

Marshall Islands | 339.8 |

Liberia | 61.1 |

Bahamas | 43.3 |

Jersey | 35.3 |

Luxembourg | 18.2 |

Barbados | 13.2 |

Guernsey | 11.2 |

Cyprus | 9.8 |

Congressional Research Service

Table I shows the top tax havens used by U.S. multinational companies, according to calculations by the Congressional Research Service. In four of these countries, profits of U.S.-controlled companies exceed the actual GDP of the host country. By comparison, profits of U.S.-controlled foreign corporations in the average G-7 country are only 0.6% of GDP. Figures such as these make clear that the profits cannot all be derived from real economic activity in these countries.

When corporations choose to locate subsidiaries and international profits in tax havens—for tax purposes—that is known as base erosion or profit shifting. Some profit shifting strategies, while completely legal, result directly in the erosion of the U.S. tax base. Others, which merely reduce companies’ foreign tax burden, are less of a concern from a U.S. policy perspective. The following are examples of profit shifting strategies used by corporations.

- Aggressive transfer pricing: Oftentimes a multinational company will conduct a sale of an asset from one of its subsidiaries to another. When the two subsidiaries are located in different jurisdictions, the price of such a sale can have significant tax implications. U.S. law requires the company to price the sale as if it were being conducted between unrelated entities at an “arm’s length.” And companies engaging in transfer pricing must satisfy reporting requirements and periodic audits. In practice, though, the arms-length price is not always obvious, especially with intellectual property (IP). In situations like these, the U.S. parent seeks to maximize expenses located in the United States and maximize profits located in low-tax jurisdictions. For example, a company may license the economic rights of IP created in the United States to a foreign subsidiary, which becomes the recipient of profits generated by that IP. The company has an incentive to minimize the license payment from the subsidiary to the parent, so that less of the parent’s income is taxable.12

- Check-the-box: This set of rules was first created by Treasury in 1996—with the goal of simplifying tax compliance—and then bolstered by legislation in 2006. Check-the-box allows multinationals to regard a corporate entity one way in a foreign country and another way in the United States. In particular, one of a multinational corporation’s entities located in a low-tax country can be designated as “disregarded,” or essentially irrelevant, for U.S. tax purposes. That “disregarded” entity may make a loan to one of the company’s entities in another country. The United States doesn’t recognize the loan or the interest payments, but the foreign country does. That means the interest paid in the foreign company can be deducted as a business expense, while the interest received by the “disregarded” entity is not registered as income. That reduces taxes paid in both the foreign country and the United States.13

- Inversion: Sometimes a U.S.-based corporation seeks to relocate its headquarters altogether. It can do so by merging with a foreign company at least one-fourth its size. For example, Chiquita announced this year it will merge with Fyffes, an Irish fruit distributor half its size. A newly formed Irish company (to be called Chiquita) will control the merged companies—Chiquita will remain listed in the United States, but its headquarters will move to Dublin.14 As a result, Chiquita will be able to locate more of its future profits in low-tax Ireland. Another incentive in many inversions is the ability for the U.S. company to deploy billions in tax-deferred earnings located in offshore subsidiaries, without having to pay the U.S. rate of 35% on that cash.15

Understandably, these sorts of tactics are often unpopular politically. The reality is that all of the above strategies are feasible under the U.S. tax system and those of multiple other developed countries. Of course, sometimes these strategies are carried out in violation of the rules, and when they are, corporations should be held accountable. (The Office of Transfer Pricing of the IRS assesses penalties on transactions that violate transfer pricing guidelines.) But in the vast majority of cases, when income shifting is done legally, the tax policies of the United States and the foreign countries themselves are to blame.

What is the OECD BEPS Project?

The prevalence of base erosion has given rise to an international effort to harmonize the tax laws of nations around the world. Because base erosion is largely made possibly by inconsistent tax laws among countries, the heads of state of the G-20 countries agreed in 2013 to develop model legislation and other practices aimed at addressing base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) in a uniform manner. They charged the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to produce model legislation, a multilateral tax agreement, and information reporting mechanisms to address base erosion issues. The OECD has begun releasing draft proposals, which cover a vast range of tax questions, including:

- How should multinationals apportion income from intangibles among countries?

- What counts as a permanent establishment for an Internet-based business?

- What should happen when a taxpayer claims a deduction in two countries for a single expense?16

The next major step in the BEPS project is for the OECD to present reports to the G-20 finance ministers at the September meeting in Cairns, Australia. Once BEPS recommendations are final, the U.S. Treasury Department could choose to issue new regulations in areas such as transfer pricing.17 Other recommendations may provide guidance which may only be followed through legislation. Some recommendations, however, the United States is likely to oppose if they threaten the competitiveness of U.S. companies or interests. For example, some provisions, if enacted by other countries, could increase the amount of foreign tax U.S. companies pay on their overseas profits, which would lower the amount of U.S. tax that can be collected if and when dividends are repatriated.

Ultimately, the BEPS initiative underscores the importance of comprehensive international corporate tax reform in the United States. If the United States cannot stop the erosion of its tax base, other countries may take unilateral action to increase taxation on profits of U.S. companies overseas. That could result in a U.S. company facing double taxation on some of their income.18 The Administration must continue to engage OECD partners to optimize the outcome of the BEPS project for the United States, but Treasury cannot fix the system alone through negotiation and new regulations. That can only be done by Congress with tax reform legislation.

What are the Major Reform Proposals?

In the last year, three policymakers presented major proposals relating to international tax reform:

- Former Senate Finance Chairman (now Ambassador) Baucus’ “International Business Tax Reform Discussion Draft” in November 2013

- House Ways & Means Chairman Camp’s “Tax Reform Act of 2014” in February 2014

- President Obama’s 2015 Budget Proposal in March 2014

Many assessments have drawn attention to the differences that exist among the plans, but on a high-level, the proposals have several important features in common. Each aims to lower the corporate tax rate to the 25-28% range by broadening the corporate tax base. Each includes some of the same “base broadeners,” such as the repeal of last-in, first-out (“LIFO”) accounting. Each would tighten rules to prevent the shifting of profits abroad, partly by expanding the types of foreign income on which corporations must pay taxes the year they are earned. Significant differences do exist, but the underlying principles provide enough common ground for tax reform to proceed.

On the international side, the Baucus proposal has been called a hybrid worldwide/territorial system. The system is part worldwide because foreign subsidiary profits are subject to U.S. tax. The system is part territorial, because some of those overseas profits receive lower, preferential rates in the form of an exclusion. Finally, a key ingredient to the Baucus plan is the end of deferral: all profits of foreign subsidiaries would be either completely tax exempt or subject to U.S. tax in the year they are earned, effectively ending the lockout effect. The Baucus proposal would reduce profit shifting by expanding Subpart F to include foreign subsidiaries’ active income derived from goods and services produced overseas but sold in the United States. Past tax-deferred earnings currently held overseas would face a one-time 20% tax, payable over eight years.19 The Baucus proposal does not specify the new top statutory rate, but Baucus himself had stated a goal of reducing it below 30%.

Similar to the Baucus draft, the Camp reform (an even more detailed proposal) would virtually eliminate the lockout effect and tighten restrictions on profit shifting. The Camp reform most differs in that it would function more like a territorial system. U.S. multinationals would be allowed a 95% deduction of foreign dividends, effectively reducing the tax rate on future repatriated income to 1.25%. Income derived from intangible property would be subject to current taxation at a minimum of 15% and a maximum of 25% (on profits from sales in the United States). Past tax-deferred earnings held overseas would face a one-time 8.75% tax (3.5% if the earnings were already reinvested in business operations). Unlike the other proposals, Camp’s reform includes a fully paid-for, specified lower corporate tax rate of 25%. Two of the most significant preferences he proposes to curtail—to finance the lower rate—are accelerated depreciation and the expensing and crediting of research expenditures.20

The President’s Budget does not include structural reforms as significant as the Camp and Baucus plans. Previously, the White House has proposed a minimum tax on overseas profits.21 The minimum tax would be similar to policies in the Camp and Baucus proposals: the amount of foreign income excluded from current taxation would be reduced, and the disincentive to repatriate earnings would be diminished. However, the President has not proposed a foreign dividend exemption, such as those proposed by Camp and Baucus, which would lower the maximum amount of taxes companies would face on foreign income. The President’s budget does include measures to reduce profit-shifting and inversions. For example, the President would expand Subpart F and limit exceptions to it. On inversions, the President would raise the minimum new ownership requirement. To avoid treatment as a U.S. company after inverting, the new company created would have to be at least 50% owned by the shareholders of the foreign partner, as opposed to the current minimum of 20%. Separately, Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI) have proposed legislation modeled on the President’s proposal.

The President’s Budget proposes an eventual corporate tax rate of 28%, with a special rate of 25% for manufacturing companies. But the preferences he proposes to eliminate do not provide enough revenue to finance a 28% rate. By most accounts, the proposed revenue-raisers, including an interest expense limitation, would be enough to lower the rate by only one or two percentage points. The White House has previously suggested additional revenue-raisers that could be used to lower the rate further: one is to tax large flow-through businesses as corporations. But some of these have not been officially endorsed in the budget.22

Conclusion

International corporate tax reform has taken several substantial steps in 2014. President Obama, Chairman Camp, and Ambassador Baucus have all presented reform options that would significantly modernize the U.S. tax code, achieve a lower tax rate, and make U.S. companies more competitive.

Surface-level summaries of the international approaches of these plans may characterize them as clashing: “worldwide versus territorial.” But they share important common elements. Each plan would end the lockout effect. Each would grow the corporate tax base by increasing the types of overseas income subject to current taxation in the United States. Baucus and especially Camp seek to boost U.S. competitiveness by reducing the effective rate on foreign-earned income. That effort could be combined with elements of the President’s plan to form a bipartisan compromise. The thrust of all of these changes is consistent with those most developed nations have made since the last U.S. tax reform in 1986.

Some skeptics point to the debate over whether corporate tax reform should generate new revenue. But on this, too, a consensus should emerge. In an increasingly globalized world, it makes less and less sense to try to squeeze more revenue out of internationally mobile entities. Policymakers should aim to improve the efficiency and the economic competitiveness of the corporate tax system. Preventing an increase in the deficit, as a result of tax reform, is important. But policymakers intent on increasing revenue would find better results by, as those in some countries have, looking to the individual side of the code.

Getting to the finish line will be difficult. But policymakers should press forward so we have a 21st-Century tax system in order to compete in a 21st-Century economy.