Report Published August 27, 2014 · Updated August 27, 2014 · 6 minute read

Nuclear Energy Renaissance Set to Move Ahead Without U.S.

Ingrid Akerlind & Josh Freed

Takeaways

- International experts have concluded that hundreds of new nuclear reactors are needed globally by 2035 to mitigate climate change.

- Significant innovation is required to reduce cost, address safety issues, and make nuclear power scalable.

- Other countries, like China, are ramping up investment in nuclear energy R&D.

- New Third Way analysis has found that in the U.S., federal funding for nuclear R&D is declining sharply just as we need it to grow.

Experts Agree: Nuclear Energy is Key to Tackling Climate Change

In early 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) climate assessment listed nuclear alongside renewables and carbon capture and storage as the technologies necessary to successfully mitigate climate change.1 The International Energy Agency (IEA) has concluded that the world needs to add the equivalent of between 270 and 410 new, large-scale nuclear reactors to electricity grids by 2035 to mitigate climate change and meet growing energy demand.2 That means potentially nearly doubling the fleet of 435 nuclear reactors that are generating electricity today. This ambitious boost in nuclear energy would be in addition to the even more significant increase in renewable energies, like wind and solar, that the IEA also calls for.3

But won’t most of this new nuclear power come from developing countries like China? Not entirely.

A 2012 IEA assessment by the found that the 34 countries that make up the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development alone will have to add more than 60 large-scale reactors over the next twenty-five years.4 This would exceed the 58 reactors currently operating in France, which has the second largest nuclear power fleet in the world (behind only the U.S., with 100 reactors).5 Moreover, 17% of the world’s currently operating 435 reactors will be sixty years or older in 2035.6 The electricity they produce will also need to be replaced with new technology.

Growth in nuclear energy requires innovation

Worldwide, the addition of 400 more reactors would bring over a trillion dollars in new capital investments,7 mainly in developing countries. This is an enormous economic opportunity for whichever companies (and countries) lead the market. That makes this an excellent time to invest in new innovations to make nuclear energy cheaper to construct and operate, sized to meet various market needs, and even safer than it is now. Moreover, they’re already on the drawing board.

However, funding such innovation in the U.S. is tricky. The costs are high; the time horizons are very long compared to other technologies; and the regulatory environment for electricity generation is fractured and difficult to navigate. Even non-nuclear energy research and development is underfunded.8 The rigorous testing and licensing phases for nuclear energy, which add huge costs and uncertainty for investors, can further discourage already skittish private investors.

OECD Countries and China are Investing in Nuclear R&D

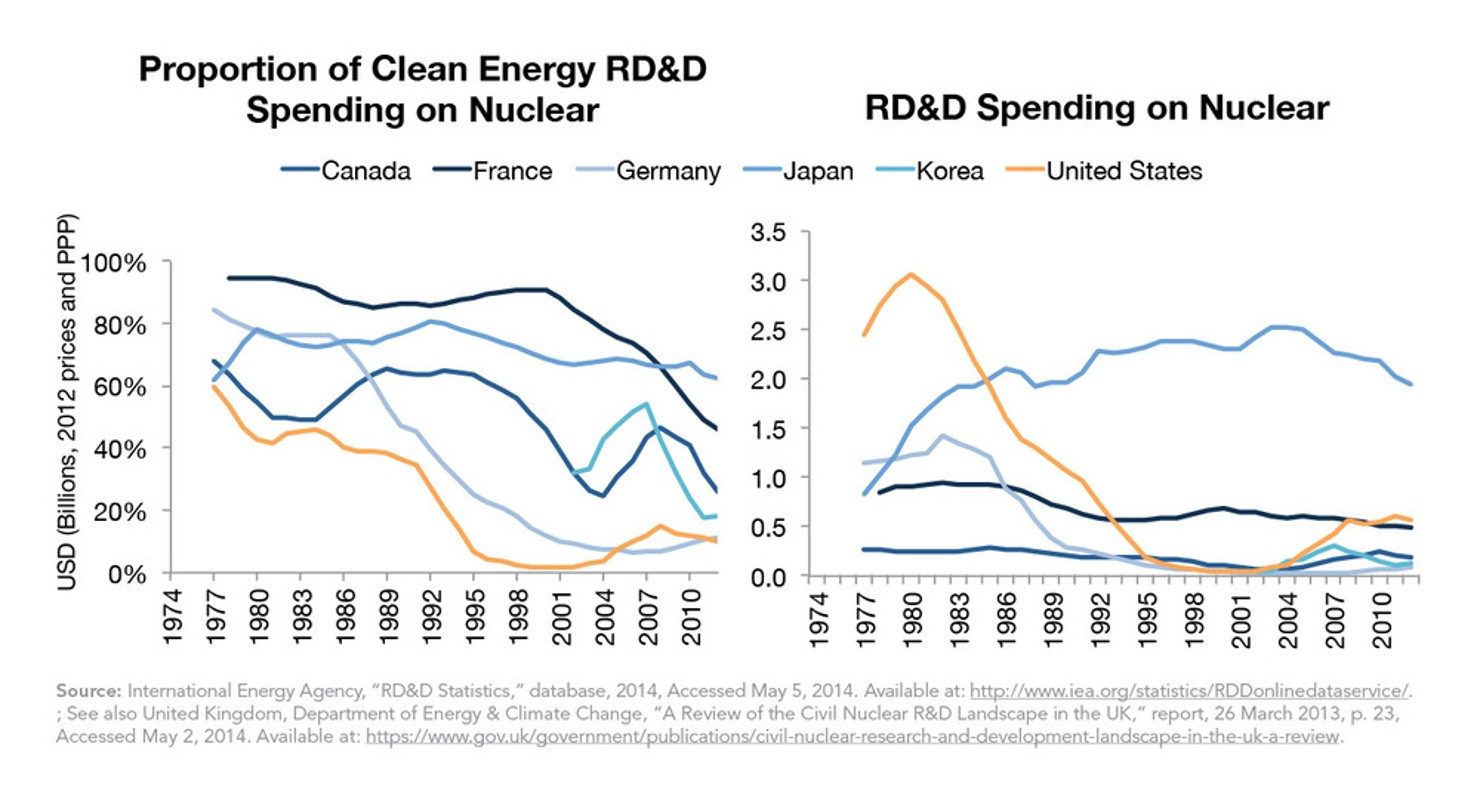

Today, the moment at which the U.S. should be ramping up its funding for nuclear innovation, it is doing the opposite and falling behind our biggest competitors. This wasn’t always the case. In 1980, U.S. nuclear RD&D exceeded that of Japan and France combined.9 Thirty years later, American investment in civilian nuclear innovation barely exceeds France’s RD&D spending and is only about a third of what Japan spends. Moreover, among all developed countries that annually spend more than $100 million on nuclear research, development, and demonstration, since the 1990s the U.S. has consistently spent a proportionally much lower share of its clean energy research budget on nuclear technology.

China is betting on advanced nuclear

With hundreds of new nuclear energy projects needed and a trillion dollars in invested capital at stake, it’s not just developed economies that are investing in nuclear innovation. China has sharply scaled up its efforts over the past decade. In 2011, it announced the largest program to date on advanced thorium reactors,10 and the central government recently accelerated the timeline for a fully functional thorium reactor to just ten years11 — lightning-fast by U.S. standards.

U.S. Funding for Nuclear R&D is Tiny and Getting Smaller

Third Way analyzed federal R&D expenditures for advanced nuclear energy in detail.12 We found that while overall nuclear energy research funding has increased, funding for advanced nuclear reactor research is small, and falling.

Just 8% of the nuclear energy budget goes directly to advanced nuclear R&D

Funding directly dedicated to advanced reactor research—the three darkest orange areas in the graph above—increased rapidly in 2008, only to dwindle in 2011. Funding shrunk 40% between 2010 and 2012 and has held steady around $120 million since.

As the graph demonstrates, the rapid growth in advanced reactor research funding in 2008 is attributed to the “Next Generation Nuclear Project.” The program was intended to create a high temperature gas reactor that also produced high temperature heat as a by-product for use in industries that need it.13 In 2011, DOE decided not to proceed with a demonstration high-temperature gas reactor,14 and program funding has predictably withered since then. Nothing has replaced the project, in funding or breadth of vision.

Research on other innovative reactor designs has received even less money. While the most cutting edge research program (“Advanced Reactor Concepts,” which is darkest orange in graph) appears to have grown in the 2015 budget, it actually shrunk by 18% because it absorbed the remnants of the two other advanced reactor research programs.

It will take a lot more to commercialize advanced nuclear

If we want successful advanced nuclear technology, we need much greater investment. From 2003 to 2010, the Department of Energy spent $670 million on the “Nuclear Power 2010” project (part of dark gray). This public-private partnership sought to help commercialize state-of-the-art large reactor technology.15 Four reactors being built in South Carolina and Georgia are the result.

The “Nuclear Power 2010” project received an average of $82 million per year in federal funding; by contrast, the most advanced reactor research program received an average of $25 million per year from 2003-13 . This is far too low to support a demonstration reactor—a program with the capacity to build advanced nuclear demonstration reactors will likely need at least $100 million per year in federal funding for at least five years.

Conclusion

As the IPCC and IEA conclude, nuclear power could and should be a major tool in the global strategy to address climate change. We are already seeing this happening as countries like China expand their reliance on nuclear power. But we will need a mix of existing and innovative new nuclear technologies to meet the world’s demand for emissions-free power. Emerging economies are ramping-up their investments in nuclear energy R&D, but the U.S. is headed in the opposite direction. That’s a big mistake for the American economy and for the world’s battle against climate change.