Report Published November 15, 2012 · Updated November 15, 2012 · 10 minute read

It Can Be Done: Five Lessons from the 1990 Budget Summit Agreement

David Brown & Jim Kessler

Our nation’s founders drafted and signed the Constitution in 17 weeks. Can today’s leaders reach their own grand bargain in seven? In 1990, a president faced a hostile Congress including rebellious members from both sides of the aisle. A fiscal cliff was steadily approaching. Politicians were hemmed in by short-sighted, politically motivated pledges. The country’s economy was underperforming. The financial markets warned of uncertainty. And the debt was steadily marching upward. As policymakers seek to avert the 2013 fiscal cliff, five lessons from the 1990 Budget Summit Agreement demonstrate why a new grand bargain is no insurmountable task.

On September 30, 1990, Congressional leaders of both parties and President George H.W. Bush announced the Budget Summit Agreement, which cut spending, raised taxes, and reduced deficits by $500 billion over five years (equal to $1.8 trillion in deficit reduction over ten years in today’s dollars). The agreement laid out savings targets in different categories, and it included a three-page memorandum of understanding (MOU), in which leaders pledged to push the deal through Congress. A month later, President Bush signed a close version of the deal into law.

In this report, we highlight five lessons from the 1990 Budget Summit Agreement—all of which are instructive to policymakers negotiating a resolution to the fiscal cliff:

- A deal can come together fast. Talks barely progressed for six months. But when the sequester neared, Congressional leaders and the White House took just 12 days of round-the-clock meetings to churn out the final deal.

- A deal can be big, balanced, and bipartisan. If passed today, the 1990 deal would have saved $1.8 trillion over 10 years. It was bipartisan, made real cuts to entitlements, and raised real tax revenue.

- Commitments matter more than details. The Budget Summit Agreement laid out precise policies in some budget areas and simply set targets in others. What mattered were the topline targets and the credible political commitments made in the MOU by all actors.

- Divisions within the parties can be overcome. Notable voices in Congress, like Republican Reps. Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey, staunchly opposed the deal through the end, as did many of the most liberal members of the Democratic Party.

- The President and Congressional leaders must lead together. Though moderate back-benchers in Congress pushed for a deal, the final agreement was negotiated by only the top few leaders in Congress and three White House officials. Each side gave ground: top Democrats acceded to cuts to Medicare. President Bush broke his famous “no-new-taxes” pledge, and he carried out a veto threat to see the deal through.

Like today’s budget debate, the 1990 showdown was born out of rising public debt, a struggling economy, and looming sequestration. U.S. public debt grew from 32% in 1980 to 55% in 1990, drawing attention to the deficit. A more urgent problem was the recession. The White House had urged Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan to lower interest rates. But Greenspan, concerned with inflation, said Congress had to cut the deficit first (to ease pressure on high borrowing rates). So, lower deficits offered the benefit of action by the Fed.

There was also the impending sequester. In 1985, Congress passed Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH), which—much like the Budget Control Act of 2011—required automatic cuts when budget caps are breached. In March 1990, the CBO’s score of the president’s budget showed sequestration was imminent.

Lesson one:

A deal can come together quickly.

Conventional wisdom holds that a grand bargain requires more negotiating time than the 2012 lame duck allows. But the 1990 agreement came together in a way that proves otherwise.

The 1990 CBO sequestration report pushed the deficit high onto the agenda. House Ways and Means Chairman Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL) warned he’d put forth his own budget for deficit reduction.1 A group of moderate Democrats led by Charlie Stenholm (D-TX), Jim Cooper (D-TN), and Dave McCurdy (D-OK) created their own plan, which applied pressure to reduce the deficit. Following the advice of his economic advisors, President Bush agreed to negotiate a deal with Congress.

Initial discussions in April and May went nowhere. Serious talks began in June and continued in September with meetings among 26 negotiators from Congress at Andrews Air Force Base. But the Andrews talks stalled over significant disagreements. Republicans, for example, insisted on lowering the tax rate on capital gains, while Democrats insisted on raising the top rate on personal income.2

With the parties still far apart, the Andrews group turned talks over to five Congressional leaders and three Administration officials. Despite outside bickering just as bad as today’s, the smaller group took just 12 days of “round-the-clock, closed-door talks” to forge a deal.3 Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, Budget Director Richard Darman, and Chief of Staff John Sununu represented the White House. The key Congressional leaders were Speaker of the House Thomas Foley (D-WA), Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell (D-ME), Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole (R-KS), House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt (D-MO), and House Minority Leader Bob Michel (R-IL). Just days before a $230 billion sequester and hours before the new fiscal year, they announced the Budget Summit Agreement in a joint press conference.4

Lesson two:

A deal can be big, balanced, and bipartisan.

With the failure of the 2011 Super Committee still fresh, skeptics of a grand bargain say both parties aren’t capable of real deficit reduction. But lawmakers in 1990, following months of bitter stalemate, successfully forged a meaningful deal. The final 1990 deal resolved many problems with the federal budget, most notably the deficit, which it reduced by $500 billion over five years (the equivalent of $1.8 trillion over ten years in current dollars).5 Savings consisted of:

- $182 billion in discretionary cuts, primarily to defense;

- $119 billion in mandatory cuts, including Medicare savings from provider reimbursement cuts and increases to deductibles and premiums ($60 billion);

- $134 billion in new tax revenue, including a phased-in gas tax increase ($56 billion), a limit on itemized deductions ($18 billion) and a variety of user fees; and

- $65 billion in interest savings.

The budget deal had several other important components. First, it included a five-year debt limit extension. Second, it revised Gramm-Rudman-Hollings to prevent sequestration. Third, the deal established “PAYGO,” requiring any tax or entitlement change to be deficit-neutral or deficit-reducing. And fourth, the deal included measures to spur growth, such as an extension of the R&D tax credit and the low-income housing credit.

The agreement was endorsed by every person at the table.

Lesson three:

Commitments matter more than details.

One excuse offered for party leaders is they can’t possibly hammer out all the details. But the 1990 deal shows that when leaders commit to the broad brushstrokes, the details can quickly follow. In some areas of the Budget Summit Agreement, a combination of specific, scored proposals totaling a savings target were shown. In other areas, like mandatory agriculture spending, a menu of options was provided. And in still other areas, like entitlement program fees, specific policies were absent, but the negotiators pledged to determine specific savings policies “prior to enactment of the reconciliation deal.”

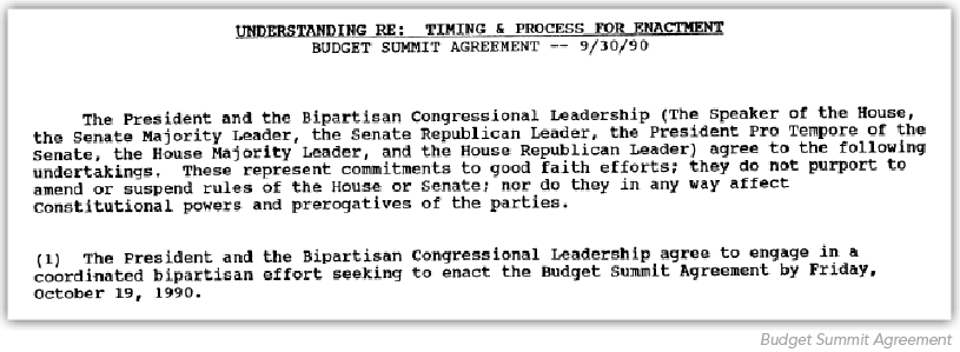

Critical to the deal’s political viability was the three-page MOU, in which President Bush and the Congressional leaders pledged:

- To “engage in a coordinated bipartisan effort” to push the deal in Congress.

- To oppose any amendments inconsistent with—or unrelated to—the deal.

- To seek support from a majority of each party in both the House and Senate.

- That the president would not sign any more temporary continuing resolutions before a conference agreement consistent with the deal passed both houses.

As the deal worked its way through Congress, specific spending cuts and tax increases were added and subtracted, but the principles laid out in the MOU ensured that legislation remained focused on the goal of $500 billion in deficit savings.

Lesson four:

Divisions within the parties can be overcome.

Even if today’s leaders can come together, some doubt a grand bargain can pass a vote, because each party has problems in its own caucus: Tea Party opposition to new revenue and many liberals’ intransigence on entitlements. There will always be well placed opposition within both parties, but it doesn’t necessarily have to stop a deal.

The MOU in 1990 gave the agreement the political backing it needed to overcome serious obstacles in Congress. Conservative Republicans like Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-GA) loudly opposed the deal, because of its new taxes and defense cuts. But President Bush maintained that while conservatives were left “gagging on certain provisions,” a budget deal had to proceed because it was “good medicine for the economy.”6

Liberal Democrats opposed the regressive tax increases—on gas, alcohol, and cigarettes—and the cuts to Medicare, agriculture, and pension programs. They complained the package lacked tax increases on millionaires and said Speaker Foley “collaborated with the enemy.”7

As a result of opposition on both sides, the first House vote on the deal failed, and instead Congress passed an extension measure October 5. Some on the left and the right, especially the Gingrich faction of the Republican Party, remained opposed to the deal through the end.

Lesson five:

The President and Congressional Leaders must lead together.

Commentators interested in a grand bargain this year lament that the leaders who talk most about compromise—like those in the Gang of Six—aren’t the ones in leadership. 1990 shows that while party leaders have to cut the deal, moderates can push them together. That year, like the Gang of Six today, a determined group of moderates sought a far-reaching deficit reduction deal. Led by Stenholm, Cooper, and McCurdy, fiscally conservative budgets were promoted as alternatives to both the Bush and the Democratic budgets of the day. In the end, the moderates provided impetus for a deal but were not at the negotiating table. They forced the leaders to come together. And they did.

As promised in the MOU, President Bush vetoed the short-term extension. He said, “It is time for the Congress to act responsibly on a budget resolution—not a time for business as usual.”8 With the veto came a short government shutdown and a public outcry largely directed at the president. Three days later, President Bush signed the first of three short continuing resolutions that month. But his message had been delivered. Congress went back to work advancing the budget deal. In the heat of the budget negotiations, Rep. Leon Panetta (D-CA), then Budget Committee Chairman, urged the House to “set aside the politics and the rhetoric and focus on where we are as a Congress and a nation.”9

On October 27, Congress narrowly passed—through reconciliation—the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA-90). On November 5, President Bush signed the bill into law.10 OBRA-90 differed slightly from the Budget Summit Agreement: The revenue portion of the deal grew by $24 billion, partly from an increase of the top marginal income tax rate, and the entitlements portion shrank by $39 billion. But the law was true to the major tenets of the negotiated deal, and it met the $500 billion target.11 Critical to the deal’s success were the commitments that leaders made in the MOU, which gave President Bush cover for his veto and ensured moderates on both sides stayed committed.

Conclusion

The 1990 Budget Summit Agreement set the stage for recovery and the Clinton budget surpluses. The improved fiscal outlook, combined with lower inflation, led Greenspan to lower interest rates in 1992. OBRA-90 and its successor, the 1993 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA-93), ensured that as the economy recovered, deficits fell continuously from 1992 through 1998, when the government began a four-year run of surpluses.12 A CBO analysis credited OBRA-90 and OBRA-93 with ensuring that between 1991 and 1997, “most new revenue and mandatory spending laws” were deficit-neutral.13

The fiscal stability of the 1990s was no accident. It was the result of strong leadership. President Bush—and after him President Clinton—compromised with Congressional leadership. In doing so, those leaders rejected easy excuses and recognized that fiscal progress requires a balanced approach. They recognized that not all partisans can be satisfied, but leaders on both sides must take charge of negotiations, compromise, and remain true to their commitments.