Report Published February 16, 2021 · 23 minute read

Follow the Money: Few Federal Grants are Used to Fight Cybercrime

Michael Garcia

Takeaways

Like traditional crime, not all cybercrime rises to the level that requires a federal response. And like other crimes, victims will call upon state and local law enforcement to respond.1 They are unprepared.

The 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the United States lack the tools, personnel, and resources to respond to cybercrime effectively. State and locals have turned to federal funding to fill these gaps, but federal government grants do not prioritize combatting cybercrime.

The Justice Department (DOJ) has never identified cybercrime as an “Area of Emphasis” for their main criminal justice grant that awards state and local criminal justice agencies $400-$550 million annually.2 And while DOJ and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provided nearly $2 billion that state and local officials could use for cyber enforcement purposes in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, data from DHS implies that very little is used for cybercrime. Only 2% of all DHS preparedness grant programs were used for all cybersecurity needs in FY 2019.3 Moreover, just three grants in FY 2019 were solely dedicated to cybercrime with a total budget of $12.7 million.4

As a result, only 45% of local law enforcement agencies have access to adequate digital evidence resources, according to one survey. This leads to a backlog of un-analyzed evidence needed to investigate cybercrime and a sense of futility about law enforcement’s ability to close cases.5

While Members of Congress have introduced several bills to create dedicated cybersecurity grant programs for state and local entities, these proposals tend to not include cyber enforcement needs as an eligible expense.6 Moving forward, Congress should:

- Call on DOJ and DHS to prioritize combatting cybercrime as a main law enforcement issue within their grants.

- Require prioritization of cyber enforcement needs in grant programs administered by DOJ and DHS in annual appropriations bills; and

- List cyber enforcement spending as an eligible expense in any bills creating new cybersecurity grant programs for state and local governments.

State and local law enforcement will increasingly be called upon to respond to cybercrime, but lack the personnel, tools, and resources to effectively respond.

There are 18,000 state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement agencies in the United States that victims are increasingly calling to investigate cybercrime but lack the means to do so.7 With the onset of COVID-19, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) and DHS warned of increasing cyberattacks against hospitals and schools that make their data inaccessible until a ransom is paid, otherwise known as ransomware.8 In August and September of 2020, DHS found a 30% reported rise in ransomware targeting K-12 schools compared to January through July of the same year.9

While arresting the perpetrators behind these attacks is difficult due to federal and international jurisdictional issues among other challenges, local law enforcement struggle to respond and assist victims because they lack trained personnel, tools, and funding. A 2013 survey of 500 law enforcement agencies found that only 42% of them had a computer crime or cybercrime unit and over half said that the lack of staffing was the biggest challenge to investigating cybercrime.10 As a result, 66% of these respondents said that they refer cases to the FBI to take the lead on investigating a case.11 SLTT law enforcement agencies also have insufficient digital forensic tools to investigate digital evidence (e.g., files, photos, text) left behind on digital devices (e.g., computers, cell phones), which impedes their ability to investigate and prosecute cybercriminals. The Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) conducted a survey in 2018 among SLTT law enforcement agencies and found that only 45% of local law enforcement agencies felt that they “had access to the resources needed to meet their digital evidence needs.”12 As a result of these challenges, a cyber enforcement gap exists, which in 2018 was quantified as only three in every 1,000 reported cyber incidents leading to an arrest, allowing criminals to operate with impunity.

The primary reason for limited staff and digital forensic tools is due to their costs, which SLTT agencies try to offset with federal funding.13 At a DOJ workshop that convened SLTT law enforcement agencies to discuss cyber enforcement challenges, or the obstacles impeding their ability to hold cybercriminals accountable, attendees pointed to costs as the primary barrier. One attendee noted that “providing necessary equipment, renewing licenses, and providing training can easily be in the tens of thousands of dollars;” a costly sum for small agencies.14 Attendees also claimed that persuading mayors and city councils to cover these costs is difficult compared to “more visible and easily understood investments” such as cop cars.15 As a result, SLTT criminal justice agencies heavily rely on federal funding to try to overcome their resource needs, yet not enough resources are available to close this gap.

While the true resource gap is difficult to determine, respondents from the DOJ workshop claimed that 95% of their digital forensics’ equipment comes from outside funding.16 Similarly, 95% of the respondents in the CSIS survey said that they sought outside assistance to examine digital evidence.17 This trend extends to cybersecurity writ large among state governments, as half of the state chief information security officers rely on DHS grants to cover their cybersecurity expenses.18 These data points illustrate that SLTT agencies are reliant on federal funding to fill their cybersecurity and cyber enforcement needs.

While existing federal grants could be used for cyber enforcement purposes, the federal government has not prioritized combatting cybercrime within these grants compared to other criminal justice issues nor sufficiently funded the few grants that are dedicated to fighting cybercrime.

Although SLTT law enforcement agencies turn to federal funding to fight cybercrime, existing grants do not prioritize or sufficiently fund cyber enforcement priorities to close their cyber enforcement gap. DHS and DOJ are the primary agencies that provided at least 11 grants in FY 2019 totaling $1.8 billion—not including Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grants19—that SLTT or nonprofits assisting SLTTs could use to mitigate cybercrime (see table below). Limited data is available on how these grants are used for cyber enforcement needs, but three data points indicate that they are not widely used to fight cybercrime. First, only three DOJ grant programs in FY 2019 were solely dedicated to cyber enforcement purposes, such as buying digital forensic tools or hiring personnel, with a total budget of $12.7 million. Second, DOJ does not prioritize cybercrime as a key funding initiative within its largest grants. For example, DOJ has never identified cybercrime as an “Area of Emphasis” for the Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant program, which is the largest criminal justice grant provided to states and locals.20 Lastly, only 2% of all DHS preparedness grant programs were used for all cybersecurity needs in FY 2019. Unfortunately, a similar breakdown does not exist for DOJ grants, and we recommend that such information be made available to better assess government-wide capacity building efforts.21

The table below details the grants that SLTT criminal justice agencies could use for cyber enforcement and the total amount allocated for those grant programs. The monetary figures represent the entirety of the grant program and not just cyber enforcement priorities.

|

Grants* |

FY 2020 |

FY 2019 |

FY 2018 |

FY 2017 |

|

DHS State Homeland Security Program22 |

$415,000,000 |

$415,000,000 |

$402,000,000 |

$402,000,000 |

|

DHS Urban Area Security Initiative23 |

$615,000,000 |

$590,000,000 |

$580,000,000 |

$580,000,000 |

|

DHS Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program24 |

$15,000,000 |

$10,000,000 |

$10,000,000 |

$10,000,000 |

|

DOJ Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant25 |

$547,200,000 |

$423,500,000 |

$415,500,000 |

$403,00,000 |

|

DOJ Community Oriented Policing Services |

$303,500,00026 |

$304,000,00027 |

$276,000,00028 |

$222,000,00029 |

|

DOJ Paul Coverdell Forensic Science Improvement Grants Program30 |

$30,000,000 |

$30,000,000 |

$30,000,000 |

$13,500,000 |

|

Economic, High-Technology, White Collar, and Internet Crime Prevention National Training and Technical Assistance Program31 |

$8,250,000 |

$8,570,000 |

$10,400,000 |

$8,681,000 |

|

DOJ Program for Statistical Analysis Centers |

$5,000,00032 |

$4,594,00033 |

$5,500,00034 |

$4,650,00035 |

|

DOJ Intellectual Property Enforcement Program |

$2,400,00036 |

$2,400,00037 |

$2,400,00038 |

$2,400,00039 |

|

Student Computer and Digital Forensics Educational Opportunities Program |

$0 |

$1,800,00040 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

Total |

$1,941,350,000 |

$1,789,864,000 |

$1,731,800,000 |

$1,243,231,000 |

*VOCA grants were excluded in this table, but one-off VOCA grants for cybercrime are detailed below. Figures in table rounded up.

Below are descriptions of how DHS and DOJ distribute these grants, their purposes, how SLTT criminal justice agencies have or could use them for cyber enforcement needs, and how Congress and federal agencies can reform them to prioritize cybercrime needs.

Department of Homeland Security Grants

Despite a DHS grant carve out for cybersecurity and grant recipients’ ability to spend on cyber enforcement needs, only 2% of all DHS preparedness grants were spent on cybersecurity in FY 2019. DHS, through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), operates eight preparedness grants to fund SLTT governments, transportation authorities, nonprofits, and private entities to prevent against, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks and other emergencies.41 Yet, realizing the threat landscape has evolved since 9/11 with increasing cyber incidents, FEMA made two notable changes to its grant programs to allow recipients to spend funds on cybersecurity. First, in FY 2018, FEMA identified cybersecurity as a “priority area” for the Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP)—the largest DHS preparedness grant that is composed of smaller grant programs—and mandated that recipients spend at least 5% of their funds on cybersecurity projects that protect critical infrastructure.42 Second, in the assessment process that FEMA uses to evaluate how SLTTs can respond to and recover from various hazards and threats—the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment—they added how resilient SLTTs are against cyberattacks.43 With these changes and grant recipients’ ability to spend funds on “software…to investigate…computer-related crimes,” per FEMA’s Authorized Equipment List, grant recipients can use DHS funding for cyber enforcement purposes.44 Specifically, the State Homeland Security Program (SHSP), the Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI), and the Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program (THSGP) are the most relevant DHS grant programs for SLTT agencies to support their ability to investigate cybercrime.

State Homeland Security Program (SHSP)—A grant within the HSGP that supports the implementation of risk-driven, capabilities-based State Homeland Security Strategies.45

Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI)—A grant within the HSGP that enhances regional preparedness and capabilities in 32 high-threat, high-density areas. These areas represent up to 85% of the cumulative national terrorism risk as determined by a FEMA assessment that is conducted across 100 metropolitan areas.46

Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program (THSGP)—A grant that provides funds to tribes to strengthen their capacities to prevent, prepare for, protect against, and respond to potential terrorist attacks.47 While it is not part of the HSGP and not subject to FEMA’s cybersecurity priority area, recipients may still spend funds on cyber enforcement needs because of FEMA’s Authorized Equipment List.48

Although recipients of these grant programs can spend funds on cyber enforcement needs, other homeland security priorities take precedent and recipients have spent little on cybersecurity needs let alone on cyber enforcement priorities. DHS reports that SLTT agencies spent only $40 million or 2% of all DHS preparedness grants on cybersecurity projects in FY 2019.49 Aggregate data does not exist on what equipment recipients purchased from FEMA’s Authorized Equipment List. In other words, it is impossible to know how much of that $40 million was spent on addressing cybercrime.

Department of Justice Grants

DOJ operates the following eight grants that SLTT law enforcement agencies could use for cyber enforcement purposes. Unlike the DHS grants, various DOJ agencies operate these eight grants and prescribe unique funding requirements for grant recipients. Therefore, recommendations on modifying these grants to prioritize cyber enforcement spending among grant recipients are tailored to each program in the following section.

Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG)

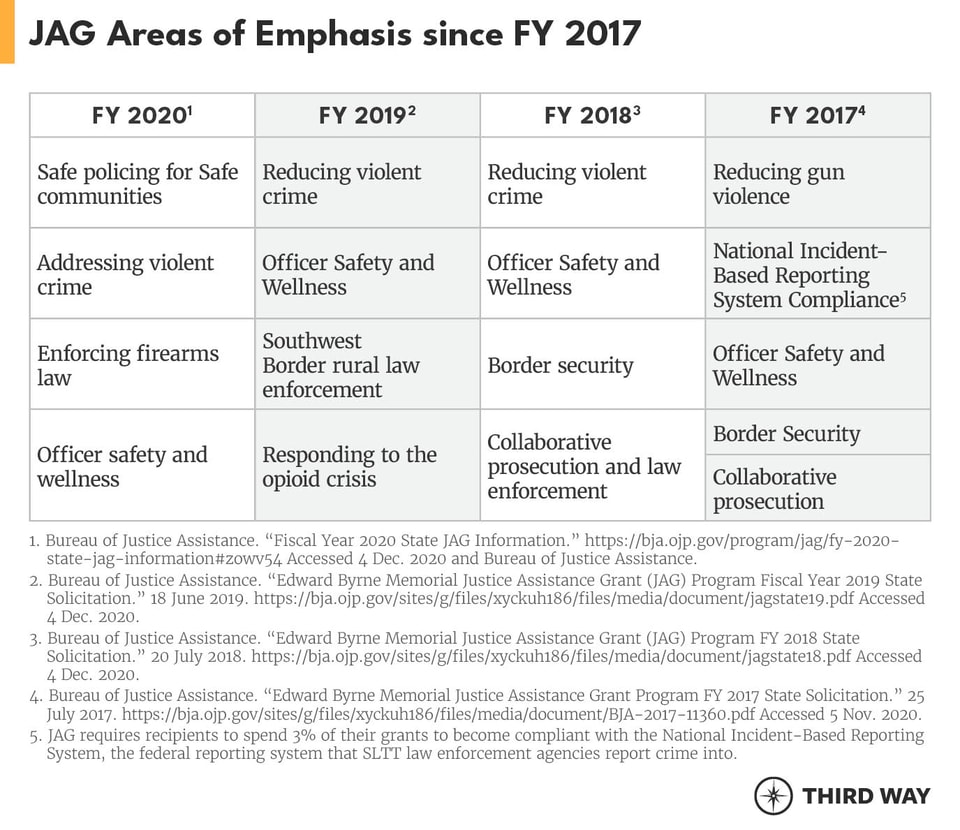

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) administers the JAG program, the primary criminal justice grant program for state and local agencies, but they do not carve out or identify cybercrime as a funding priority.50 Recipients can use JAG funds for a wide range of criminal justice issues,51 but BJA can prioritize issues by requesting that Congress carve out portions of the grant for specific projects or by identifying “Areas of Emphasis” that it encourages—but does not require—recipients to spend funds on. For example, in their FY 2021 proposed budget, DOJ asked Congress to carve out $11 million for a rural law enforcement violent crime initiative.52 Areas of Emphasis, on the other hand, have been identified by DOJ since FY 2017 and are detailed in the JAG notice for funding opportunities to encourage grant recipients to spend funds on certain criminal justice areas.

The table below details the Areas of Emphasis for the JAG program since FY 2017.53

While BJA does not preclude recipients from using JAG funds for cyber enforcement needs, BJA could further incentivize recipients to spend funds to fight cybercrime by carving funding out or identifying it as an Area of Emphasis. Some recipients have used JAG funding for cyber enforcement needs, but it is unknown how much has been spent for these purposes. In Hawaii’s FY 2020 grant application, for example, they list cybercrime as a project area they would use JAG funds to support.54 Missouri, too, detailed in their 2016 JAG Summary Report that they used funds to help support a Cybercrimes Task Force.55 Additionally, states may have included fighting cybercrime as an objective in their new JAG strategic plans, which started in FY 2019 and describes how states will use their JAG funds for the next five years.56

Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS)

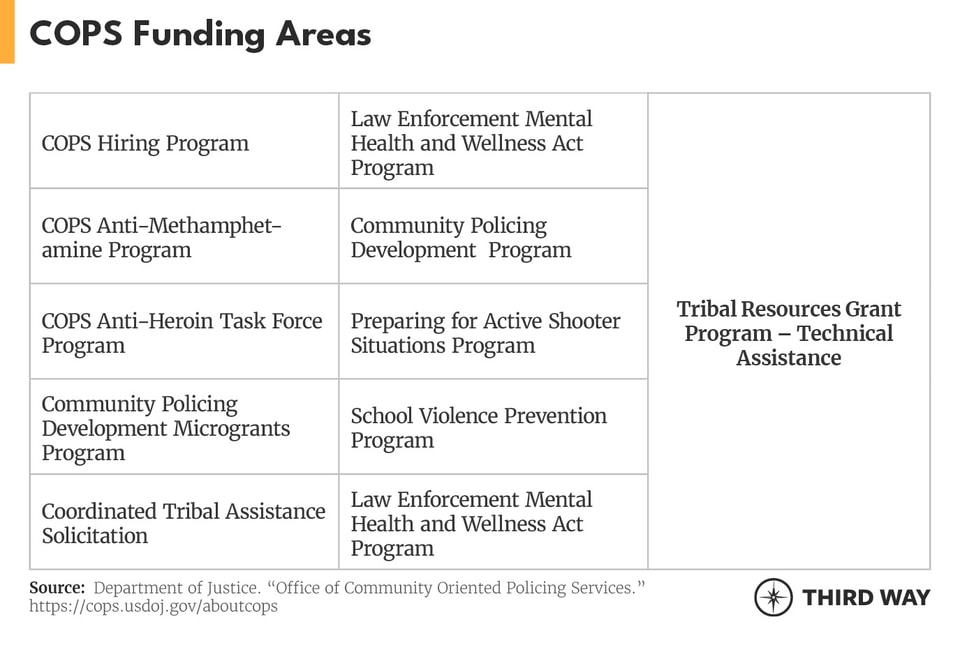

The COPS program is the second-largest criminal justice grant provided to SLTT agencies and, while not currently used for cyber enforcement, could have language clarified to allow recipients to spend funds on fighting cybercrime. The DOJ COPS Office operates the COPS program, a $200-$300 million annual program, to advance community policing throughout the country.

The COPS Office allows recipients to spend these funds on the following areas:57

Although these areas do not have direct ties to cybercrime, BJA could clarify that recipients can use COPS funds to respond to the needs of cybercrime victims.58 Ensuring community policing efforts prioritize addressing cybercrime is critical because it is a form of crime that overwhelmingly impacts Americans. Indeed, one in four American households have been victimized by cybercrime, yet only one in ten cybercrime victims report it to law enforcement.59 Incorporating community policing practices into cyber enforcement, according to the SANS Institute, would help encourage victims to report incidents of cybercrime to law enforcement.60 This will further help the government understand the true scope of the problem and provide quantitative evidence for the need to provide more funds to combat a serious issue.

Paul Coverdell Forensic Science Improvement Grants Program (Coverdell Program)

The Coverdell program could become a primary funding source for state and locals to improve their digital forensic capabilities. DOJ’s BJA administers the Coverdell program to improve forensic sciences, medical examiner/coroner services, and services provided by SLTT laboratories, including digital forensics.61 A recipient can use this grant to tackle cybercrime by “eliminat[ing] a backlog in the analysis of forensic science evidence, including…digital evidence” and training, assisting, and employing personnel to eliminate such a backlog.62 BJA further defines “forensic science laboratories” as entities whose “principal function is to examine, analyze, and interpret physical and/or digital evidence in criminal matters.”63 Some SLTT recipients have seized upon this grant to bolster their digital forensic needs, such as Bronx County in New York.64

Grant recipients, however, are currently limited in how much they can spend on improving their digital forensic capabilities. The program consists of two grants, a formula and a competitive grant, with 85% of the total funding allocated through a formula grant awarded to all 55 states and territories.65 Starting in FY 2018, 57% of a state’s formula grant had to be spent on opioid-related expenses and was increased to 64% in FY 2020.66 Therefore, in FY 2020, less than $14 million of the formula and competitive grants could be used for non-opioid related matters. Congress should work with the Attorney General to identify ways to provide more funds to the state and locals to support their digital forensic needs.

Economic, High-Technology, White Collar, and Internet Crime Prevention National Training and Technical Assistance Program

This is one of three DOJ grants that have been solely dedicated to cyber enforcement since FY 2014 and provided to a nonprofit that trains SLTT law enforcement personnel. BJA has awarded this grant since FY 2014 to the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C), a nonprofit that provides training and technical assistance to SLTT and federal criminal justice personnel to combat cybercrime.67 NW3C annually receives $6-10 million to perform these activities,68 and in FY 2018 they trained roughly 16,000 criminal justice personnel through online and in-person classes.69 With SLTT agencies unable to train personnel in person due to COVID-19, NW3C saw a dramatic increase in demand and virtually trained over 100,000 personnel between October 2019 and September 2020.70 With the effects of COVID-19 lingering for the foreseeable future, NW3C and other nonprofit organizations will be critical partners for federal and SLTT criminal justice agencies to provide online training and technical assistance for their personnel.

State Justice Statistics (SJS) Program for Statistical Analysis Centers (SACs)

The SJS program allows states to analyze cybercrime statistics, but DOJ has not prioritized the analysis of cybercrime since 2009. DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) operates the SJS program to provide states financial assistance for establishing and operating SACs to collect, analyze, and disseminate justice statistics, including cybercrime statistics.71 In FY 2020, BJS awarded $5 million to recipients—who could each receive up to $225,00072—to support “Topical Areas” such as “research using incident-based crime data that are compatible with [the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)].”73 Because “hacking/computer invasion” is a category within NIBRS,74 the federal database that law enforcement agencies input crime data, states could use this grant to analyze cybercrime. Further, in 2009, BJS identified cybercrime as a Topical Area and that SJS funds could be used for “examin[ing] the magnitude and consequences of computer crime and identity theft and fraud…and [for developing] the measurement methods, definitions, and protocols to obtain uniform data on criminal activities involving computers and computer networks and the response of the criminal justice system to violations of computer crime statutes.”75 BJS, however, has not identified cybercrime as a topical area since 2009 nor mentions cybercrime in their notice for funding opportunities.

Intellectual Property Enforcement Program (IPEP): Protecting Public Health, Safety, and the Economy from Counterfeit Goods and Product Piracy

The IPEP program is one of three grants solely dedicated to cyber enforcement, but DOJ should consider expanding its purview beyond intellectual property (IP) enforcement to allow recipients to spend funds on all types of cybercrime. BJA administers IPEP to improve SLTT criminal justice systems’ capacity to address IP crime, including prosecution, prevention, and training.76 This grant is unique compared to other DOJ grants because it requires the recipient to create or support an existing IP enforcement task force, which consists of SLTT and federal law enforcement agencies that investigate and prosecute criminals who steal IP.77 While this is a small grant ($2.4 million for FY 2020),78 the IPEP grant could present an opportunity for states and locals to build off an organizational structure that initially addresses IP crime and then expands to include other forms of cybercrime.

Student Computer and Digital Forensics Educational Opportunities Program

This is one of three DOJ grants solely dedicated to cyber enforcement to fill the workforce gap but has only been authorized once, thereby limiting its impact. In FY 2019, BJA launched this new program to partner with higher education institutes to “further educational opportunities for students in the fields of computer forensics and digital evidence” to fill employment gaps in SLTT and federal law enforcement agencies.79 With 3,000 public sector jobs for analysts and investigative positions going unfilled,80 improving and expanding the educational pipeline to fill cyber enforcement positions is critical. BJA awarded four grants under this program totaling $1.8 million to:

- Evaluate current forensic- and digital-based curricula and their alignment with the needs of SLTT law enforcement;

- Enhance and expand on existing computer forensic and digital evidence degree- or certificate-based curricula by adding a field-based, practical element to the current curricula;

- Expand access to existing training via web-based learning and/or regional, tribal, and federal collaboration;

- Define a methodology that will allow students to locate potential internships, co-operative work opportunities, and jobs in the areas of computer forensics and digital evidence; and

- Identify a corroborative approach that will enhance the development and implementation of classes proposed.81

Since the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019 (P.L.116-6), Congress has not reauthorized this program for FY 2020 or FY 2021 nor has BJA requested its reauthorization.82

Victims of Crime Act’s (VOCA) Grants

VOCA grants have at least three times been allocated to nonprofits to assist victims of cybercrime, but, unlike victims of violent crime, direct compensation and other services provided to cybercrime victims are limited. DOJ’s Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) allocated $2.7 billion through various VOCA grants to SLTT governments and other institutions in FY 2019 to provide monetary relief and other assistance to victims.83 Since FY 2010, OVC has awarded at least three grants to nonprofits to help cybercrime victims:

- An FY 2010 grant that established the National Identity Theft Victims Assistance Network to expand and improve the outreach and capacity of victim service programs to identify theft and cybercrime victims.84

- An FY 2016 grant for assessing the availability of cyberviolence training and the training needs of judicial professionals; identifying the needs of victims and survivors of cyberviolence; and developing and publishing training and technical assistance to judicial professionals.85

- An FY 2018 grant awarded to the Cybercrime Support Network for establishing a hotline for cybercrime victims and improving response efforts for those victims.86

Despite these activities, direct compensation to cybercrime victims is limited. A 2019 OVC report found that assistance provided to victims of identity fraud and other fraud is limited and focused on repairing financial damage.87 OVC also found that services for addressing the legal, emotional, and physical health needs of victims are rare and that victim compensation is often limited to those who experience violent crime due to states’ laws.88 Similarly, federal policies and laws—such as the 2012 Attorney General’s Guidelines for Victim and Witness Assistance; OVC rules for the victim assistance program; and the Victims’ Rights and Restitution Act and the Crime Victims’ Rights Act—detail how VOCA grants could support victims and defines “victim” and “harm,” but are outdated and exclude various forms of cybercrime.89 Although OVC should be commended for its work in supporting nonprofits to support cybercrime victims, other federal and state policies must be adapted to provide direct assistance to cybercrime victims.90

Congress should work with the incoming DHS Secretary and Attorney General to implement changes to expand the availability of cyber enforcement resources, while introducing appropriations and legislation that supplement these changes.

To fill the cyber enforcement funding gap, Congress should request that federal agencies prioritize cybercrime in their grant programs, use the appropriations process to provide funds for SLTT cyber enforcement needs, and add cyber enforcement funding in new legislation that creates cybersecurity grants. Further, as Congress determines how to close the SLTT cyber enforcement gap, they must consider what baseline capabilities SLTT agencies must possess to determine the appropriate amount of funding those agencies should receive and how to evaluate the return on investment of these grants.

Congress can work with the new DHS Secretary and Attorney General to institute several changes to expand the availability of SLTT resources to support cybercrime investigations that do not require legislative changes. This should include requiring:

- DHS to highlight in their notice for funding opportunities that the cybersecurity priority area for SHSP and UASI can be used to purchase equipment for improving law enforcement’s digital forensic capabilities. DHS should also determine whether the “Authorized Equipment List” needs to be expanded to allow recipients to purchase additional digital forensic software and hardware.

- DOJ to make cybercrime an “Area of Emphasis” for the JAG program for FY 2022 and request that states add an addendum to their JAG strategic plan to detail how they will combat cybercrime.

- DOJ to identify cybercrime as a topical area for the SJS program for FY 2022, which it has not done since 2009.

- BJA should work with Congress to determine why the Student Computer and Digital Forensics Educational Opportunities Program was not continued and explore the possibility of providing new resources to it.

- DOJ to improve cybercrime-victim assistance by (1) updating the 2012 Attorney General’s Guidelines for Victim and Witness Assistance to explicitly account for victims of cybercrime outside of stolen personally-identifiable information; (2) publishing an updated OVC rule that clarifies the eligibility of the Victim Assistance Program to include victims of cybercrime and expands the allowable costs that include legal support services, mental health counseling, and other services; and (3) working with states to update their laws to allow victims of cybercrime to receive OVC funds.

- DOJ to determine if legislative changes are needed to expand their grants to cover cyber enforcement and work with Congress to implement those changes.

Additionally, Members of Congress should include changes in the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies and Homeland Security appropriations bills to increase support for SLTT agencies’ cyber enforcement needs by:

- Ensuring adequate funding to HSGP and THSG to enable a mandate that recipients spend at least seven to ten percent of their funds on cybersecurity needs, which would be two to five percent more than currently mandated. These funds could also be offset by placing a heavier emphasis of cybersecurity threats and risks in the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment, the assessment that FEMA uses to determine the capabilities the Nation needs to manage incidents, to better account for the capacity needed to mitigate those threats compared to others.

- Allocating at least 5% of the JAG program for cyber enforcement needs, which is how much FEMA currently sets aside for their cybersecurity priority area.

- Requiring DOJ to submit a report to the respective judiciary committees in Congress on whether COPS could be used as a grant vehicle to provide cyber enforcement funding to SLTT criminal justice agencies.

- Increasing funds to the Paul Coverdell Forensic Science Improvement Grants Program and requiring the Attorney General to prioritize competitive grants that would support digital forensic labs and tools.

- Providing additional funds for IPEP and expanding its mission to combat other forms of cybercrime.

- Establishing a higher cap for VOCA funding to ensure states can compensate cybercrime victims.

Lastly, Members of Congress introduced several bills in the 116th Congress to create cybersecurity grants for state and locals—such as the State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act (H.R. 5823),91 the State Cyber Resiliency Act (S.1065),92 and the State and Local Government Cybersecurity Act of 2019 (S.1846)93—to provide funds to bolster their cyber defenses. Should these bills be reintroduced in the 117th Congress, they should explicitly call for cybercrime investigation and digital evidence capabilities to be eligible expenses under these new grant programs. Other bills from the 116th Congress that were not passed, such as the Technology in Criminal Justice Act of 2019 (H.R.5227)94 and Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R.1585 and S.2843),95 have provisions on these priorities that could be incorporated in new bills. Congress should also determine if the Victims’ Rights and Restitution Act and the Crime Victims’ Rights Act —which provides certain rights to individuals who meet the statutory definition of “victim” and “harm”—must be amended to account for cybercrime and, if so, introduce legislation to account for the needs of cybercrime victims.96

Conclusion

Cybercrime will continue to ravage schools, hospitals, and small businesses, and victims will continue to call local law enforcement agencies to respond. While the criminals behind these crimes may not reside in these agencies’ jurisdictions, the federal government should help equip these agencies to respond to these crimes and assist victims, who otherwise have no recourse or means to seek justice. Modifying and/or creating federal grants to provide more resources for SLTT agencies to close their cyber enforcement gap is one of the first, and critical, steps to taming the cybercrime wave.