Report Published May 3, 2016 · Updated May 3, 2016 · 13 minute read

Boosting American Exports

Paul Lapointe

By 2020, half of the world’s middle-class consumers will be in Asia. By 2030, the Asian middle-class will include 3.2 billion people—2/3 of the world’s total middle-class and ten times the current population of the United States.1 As these foreign customers look to buy more goods and services, who will they buy from?

In this brief, we look beyond trade deals and propose two additional solutions to help America sell more products to foreign consumers. First, we lay out steps for policymakers to boost resources to help more small businesses export. Second, we propose restructuring the way federal export promotion programs are organized to better align them with the strategic goal of increasing exports. These ideas will help thousands of purely domestic businesses who have exportable products join the ranks of exporting companies.

The Problem: Too Few American Companies Export

There are over 1.2 million businesses in the United States that produce goods, yet only a quarter of them are known to be exporters.2 That so few American companies export means that emerging foreign middle-class consumers, who could be buying American-made products, will instead be buying German, or Brazilian, or Vietnamese—putting the United States and American businesses at a huge disadvantage in global markets.

Getting non-exporting companies to enter foreign markets is no small task because exporting is still a daunting proposition to many small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This is due to a web of varying and intricate rules, regulations, and procedures that a company needs to understand in order to sell overseas. This hurdle is big enough that many companies never take the first step in trying to export, despite being interested.

The National Small Business Association (NSBA) found that 63% of non-exporting small businesses would be interested in exporting. When asked what their main barriers to exporting are, the #1 cited reason was they “don’t know much about it and not sure where to start.”3 Further, these non-exporting companies were asked what types of support from the federal government would be most helpful in getting them to export; the top two answers were to “make more export training and technical assistance readily available” and “consolidate various exporting assistance offerings from different federal agencies.”4 Separately, Stone & Associates—a research and consulting firm that specializes in manufacturing competitiveness—conducted an analysis showing that there are 25,000 to 80,000 SME manufacturers that currently do not export, but have a product or service that is differentiated enough to succeed in global markets and a willingness to commit to exporting—otherwise known as threshold firms.5

The Opportunity: Getting More SMEs to Export The Census Bureau’s most recent Profile of Exporting Firms identified about 72,000 small- and medium-sized manufacturers who exported in 2014, with a total export value of $169 billion.6 Stone & Associates conducted an analysis showing that there are an additional 25,000 to 80,000 small- and medium-sized manufacturers that currently do not export, but have a product or service that is differentiated enough to succeed in global markets and a willingness to commit to exporting.7 Getting these non-exporting firms to export at the same rate as their peers would potentially increase American exports by between $59 and $189 billion annually. And, extrapolating this to the non-manufacturing small- and medium-sized sector could increase American exports between $168 billion and $539 billion.8 |

The federal government has a slew of programs intended to increase and monitor trade—from negotiating and enforcing trade agreements, to assisting U.S. businesses in navigating foreign markets, to offering matchmaking services to connect domestic and foreign entities. In fact, the Congressional Research Service reports that there are 20 agencies involved in export promotion to some extent, with the vast majority of federal activities in the area confined to nine key agencies:

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA),

- Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration (ITA),

- Trade Development Agency (TDA),

- U.S. Trade Representative (USTR),

- Export-Import Bank,

- State Department’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs,

- Small Business Association’s Office of International Trade,

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), and

- Department of the Treasury.

Since 1992, these agencies have been collaborating on trade strategy via the Trade Promotion Coordinating Committee (TPCC). Through the TPCC, these agencies are required to submit an annual report on their combined export promotion strategy. Efforts to coordinate strategy went even further in 2010 with President Obama’s National Export Initiative (NEI), which established a cabinet consisting of the leaders of agencies involved in export promotion.

While there is significant government investment, too few businesses are aware of these services, and there are too many overlapping programs for companies to have to navigate.

Just take awareness of federal efforts. Federal export promotion services can be incredibly valuable to businesses looking to export. But, as the NSBA survey showed, only 15% of non-exporting small businesses indicated that they knew about U.S. Export Assistance Centers (USEAC)—offices scattered across the country that are meant to serve as the front-door to federal trade services.9

And while the federal government has started to ensure that the myriad trade promotion programs are working together with the Export Promotion Cabinet, there is still a thicket of bureaucracy standing in the way. Frankly, there will always be limitations to how much nine different agencies can align on a single mission. Each agency still has a unique primary mission, which will invariably influence every program that they operate. Additionally, even when the members of the Cabinet come to an agreement, they still need to carry out actions through their individual agency bureaucracies. Further, interagency rules and restrictions on data and cost sharing increase the administrative burden of operations.

Recent GAO reports show the limitations in cross-agency collaborations. One report revealed that the TPCC lacks comprehensive information on resource allocation across different agencies, limiting their ability to evaluate whether resources are properly distributed to best achieve the TPCC’s goals. Another report showed substantial overlap in services between programs housed in the Small Business Administration, Department of Commerce, and the Export-Import Bank—resulting in an inefficient use of resources and confusion among small businesses on where to go for assistance.10

For American businesses and workers to succeed in a rapidly changing economy, we need to make sure that as many foreign consumers are buying American goods and services as possible—especially as American companies wade in to new sectors and the internet makes it easier to increase exports. To do that, policymakers should build upon the success of the NEI with two policies to get more American SMEs exporting.

Solution #1: Alter Mission and Boost Resources for the U.S. Commercial Service

Policymakers should make reforms to the International Trade Administration to increase assistance to non-exporting businesses. To do that, they should take the following three steps:

- Give the ITA a specific mandate to support currently non-exporting companies;

- Boost resources for U.S. Export Assistance Centers; and

- Conduct an assessment of the network of U.S. Export Assistance Centers and re-organize them based on that assessment.

Case Study: Fargo Automation Fargo Automation, a medium-sized company in North Dakota, has been manufacturing automated packaging equipment for pharmaceutical and medical device companies since 1996.# It wasn’t until recently, though, that they decided to look beyond the U.S. for expansion. Despite their track record of success in domestic sales, the company’s management wasn’t quite sure where to start. Therefore, they reached out to the local U.S. Export Assistance office for help. Through the office, they were connected to the U.S. Commercial Service’s Gold Key Matching service, providing Fargo Automation with customized, in-depth assistance that helped them identify and execute overseas deals. The fact that the company is now successfully exporting to Ireland shows the opportunity that federal export promotion programs can provide to small- and medium-sized companies like Fargo Automation.# |

Give the ITA a specific mandate and performance metrics to support currently non-exporting companies.

The International Trade Administration, through the U.S. Commercial Service, helps SMEs learn how to export, connects them with customers and other business partners overseas, and finances transactions. Yet, these programs are not specifically tasked with finding companies that are not exporting and educating them on the services that they provide (as evidenced by the fact that, between 2008 and 2010, only 5% of successful cases for the Commercial Service were with firms that were new to exporting11). By including a mandate, through legislative means or an executive order, to recruit and assist non-exporting SMEs, policymakers can direct resources to unleash the untapped potential of American businesses.

In conjunction with the mandate, specific performance measures should be set to ensure that efforts are made towards this goal. Potential performance measures include:

- The number of new SME exporters in the last 12 months;

- The total amount exported by new SME exporters;

- The number of non-exporting SMEs contacted through recruitment efforts; and

- Customer service metrics for non-exporting SMEs contacting a USEAC, such as response time and customer satisfaction surveys.

Boost resources for U.S. Export Assistance Centers (USEACs).

Simply directing the U.S. Commercial Service to target non-exporting SMEs without giving them additional resources would detract from the valuable support that they provide to current customers. Therefore, this new mandate should come with additional resources to increase staff at USEACs. There are currently 350 trade specialists at about 100 USEACs. Adding up to five additional personnel to each USEAC would provide these facilities the staff that they need.

These new personnel should include dedicated marketing and recruiting specialists, whose primary function would be to identify companies with the potential to become exporters and conduct outreach to inform them of potential overseas markets and support that they could receive from the federal government. Other new staff would include additional trade specialists, staff assigned to coordinate with state and local agencies with similar missions, and administrative staff to ensure that trade specialists can focus on helping businesses and not conducting administrative tasks. These new personnel should also be trained to help companies navigate new, digital opportunities to bolster trade and access foreign markets. This is especially important as SMEs that embrace the Internet are more likely to sell products and services outside of their region.12 Based on current USEAC costs, this ramp up in staff would cost approximately $43 million per year.13

Conduct an assessment of the network of U.S. Export Assistance Centers and re-organize them based on that assessment.

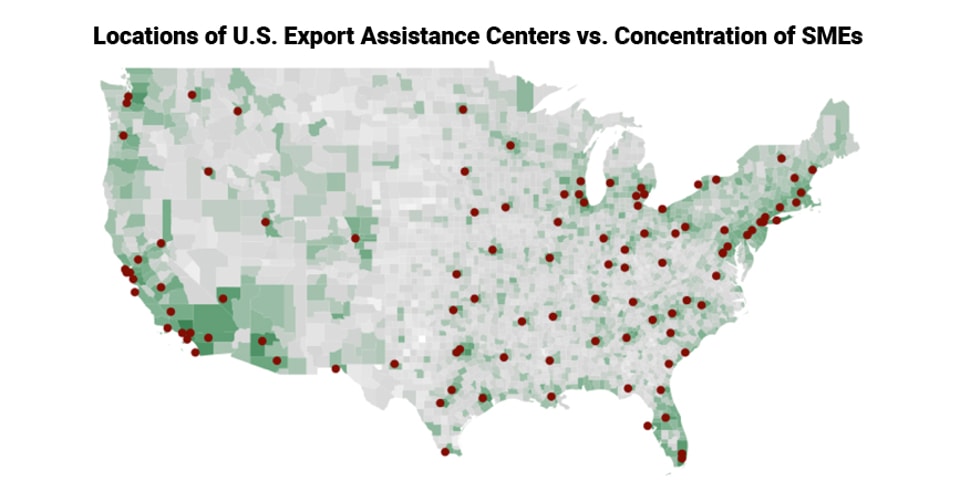

The process of ramping up the scope and capacity of the USEAC network provides a good opportunity to reassess whether or not current offices are in the most optimal locations. A quick comparison of where USEACs are located vs. the concentration of SMEs shows that most USEACs are located in spots where they can reach the most customers, but there are some regions with high concentrations of businesses where there is no local access to a USEAC (see below map).

The above map shows the locations of USEACs in the continental United States with red dots. The county-level concentration of small- and medium-sized enterprises (as measured by the log of the number of companies with less than 500 employees) is depicted via shades of green, where darker shade represent more companies.

For example, the 5,500 SMEs in Yellowstone County, Montana need to drive 9 hours to get to the nearest USEAC (in Boise, ID). Mobile County, in Alabama, is home to 8,500 SMEs, yet those business owners would need to go to Birmingham, New Orleans, or Tallahassee to work with a USEAC. Furthermore, Norfolk, VA is home to the 14th largest port in the country, but has no USEAC. While businesses in these locations can still access services online, there is no dedicated office conducting outreach in these communities or available to provide personalized services—making it less likely that they ever receive support.

These places may or may not be the right locations for a new office, but they highlight the need to reassess the trade promotion footprint across the country. To this extent, Congress should instruct the U.S. Commercial Service to conduct a review of current and potential USEAC locations and make recommendations as to the locations that would provide the most potential to help American SMEs export. In doing so, they should be authorized to identify up to 30 new locations that are currently un- or under-served by the existing network. Once the assessment is complete, Congress would need to determine whether or not the transition (and potentially increased operating costs) justify making the changes.

A recently introduced bill from Rep. Cheri Bustos (D-IL) takes on all three of these issues. The Boosting America’s Exports Act directs the U.S. Commercial Service to design metrics and set goals relating to new-to-exporting firms served by the agency’s programs. It ensures that USEACs conduct outreach to non-exporting firms, and it calls for an assessment of whether USEACs are optimally located in order to reach small- and medium-sized businesses and a plan to Congress on under-performing locations to close and new locations to open.

Solution #2: Consolidate Federal Export Promotion Programs into a Single Agency

Policymakers should also streamline federal export promotion services into a single agency dedicated to helping American companies compete worldwide, similar to what President Obama proposed in his FY2016 budget.14

This new trade agency would reside in the Department of Commerce and would consolidate the following organizations:

- The International Trade Administration

- The Overseas Private Investment Corporation

- The Office of International Trade (currently in the Small Business Administration)

- The Trade Development Agency

- The Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agriculture Service, Export Credit Guarantee Program, and Facilities Guarantee Program

- The State Department’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs

- The Export-Import Bank

This new agency would be headed by an undersecretary in the Department of Commerce, who would also sit on the President’s National Economic Council. Further, the agency would receive direct appropriations from Congress.

As part of the reorganization, the Secretary of Commerce would be tasked with recommending an organizational structure that consolidates similar programs and identifies a streamlined strategy for assisting American businesses, workers, and consumers. We recommend that Congress request a plan for the new organizational structure within 12 months, and then the department would have a further 12 months to execute the reorganization. Congress would also need to appropriate funds specifically for this purpose.

Having the majority of the federal government’s programs and services for trade promotion under one roof would have multiple benefits. The primary benefit would be better strategic alignment on export promotion. Additionally, it would lead to better utilization of resources, including the U.S. Export Assistance Center network. Lastly, it would allow the federal government to better leverage talent and expertise within these departments to help the most Americans possible. Rep. Ann McLane Kuster (D-NH) is currently developing legislation that would consolidate federal export promotion programs.

Conclusion

A robust trade-focused agenda is necessary for the American economy to compete in the 21st century. Part of this needs to be the passing of trade agreements that level the playing field for American companies and reduce barriers to trade, but efforts cannot stop at the signing of such deals. We need to ensure that companies are aware of and able to access the various services that the federal government can provide in facilitating exports.