Memo Published April 8, 2019 · 13 minute read

Understanding Net Neutrality

Gabe Horwitz

Adults in the United States spend 3 hours and 48 minutes on their computers, smartphones, and tablets every single day.1 In fact, you’re probably reading this explainer on one of those three devices right now. And to get to this document’s webpage or, for that matter, Netflix, Twitter, ESPN, or Instagram, consumers want to make sure they can surf online fast and access whatever they want when they want.

Enter net neutrality.

Since the early 2000s, net neutrality has been a perennial tech issue debated among policymakers. The idea itself is straightforward: Net neutrality is the principle that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) equitably provide consumer access to any legal online content and application, regardless of the source. Put another way, ISPs (e.g. Charter, Verizon, AT&T, Comcast Xfinity, and others) cannot block or slow legal content flowing through their networks.2

While the concept may sound simple, the debate in Washington has been far from that. The rules that govern this space have shifted back and forth, as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has tried to figure out what it can and should do to protect consumers. Currently, the FCC has removed explicit rules barring ISPs from blocking or throttling traffic. Instead, they have chosen to only require ISPs to disclose how they handle consumers’ traffic and rely on Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforcement if ISP practices violate those terms.3 States and other policymakers have reacted to this decision, and the debate of how this area should be regulated continues.

To help policymakers understand this issue and engage in the current legislative discussions on the topic, this memo unpacks the consumer protections being discussed, the regulatory framework up for debate, and some brief background on how this issue has evolved.

Consumer Protections

To understand this debate, it’s best to start with the specifics of how net neutrality affects the average consumer. Some commonly used terms in this debate include the following:

Blocking

Blocking refers to the ability to prevent a consumer from accessing certain legal websites and content providers.4For example, under blocking, an ISP could stop a consumer from accessing a competitor’s website. It should be noted that many internet companies have overtly stated they would not practice blocking—highlighting that they would have no incentive to do so in a competitive market for consumers.

Throttling

Throttling is the ability to slow or interfere with the transmission of content to a consumer.5 For example, an ISP that is throttling might allow a consumer to access a particular website but only at a slower speed or lower-quality transmission. Consumer advocates warn that internet providers can slow access to companies that do not pay for prioritization as a way of punishment. Like blocking, most internet providers have explicitly pledged not to throttle or censor any online content, pointing again to their desire to compete with other providers to provide speedy access to anything consumers demand.

Paid Prioritization

Paid prioritization refers to the ability to charge additional fees to content producers for faster delivery of their content. For example, using this technique, a website could pay for their content to be delivered to consumers faster than those who do not pay.6 This type of prioritization is sometimes referred to as “internet fast lanes.”

Consumer advocates argue that if content providers can pay for faster internet speeds, it unfairly penalizes smaller companies and startups who may not have the funds to do so. As a result, they argue that consumers could see less content, and fees could also trickle down to the consumer.

ISPs argue that they lack incentives to engage in harmful paid prioritization since consumers can shift to alternative providers if the content they wish to access is restricted. Many ISPs have committed that they will not accept payment to deliver internet traffic to consumers faster or sooner than other internet traffic. They also argue that they need some reasonable flexibility to manage traffic on their networks to avoid congestion for customers (e.g. treating video streaming differently than uploading a photo to a social media account).

Transparency

Transparency refers to requirements that ISPs must disclose how they manage their networks.7Currently, the FCC requires ISPs to include disclosures on any blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization that internet service providers might practice. Transparency rules have been included in past net neutrality regulations, but play an even larger role in the absence of net neutrality.

There is fairly widespread acceptance of the need for transparency. However, consumer advocates argue that relying on FTC enforcement alone is not a strong enough regulation, and there needs to be additional rules authorizing direct FCC enforcement of “bad practices” such as blocking or throttling.

General Conduct Standard for ISPs

In 2015, the FCC established a new standard so it could determine whether internet technology practices developed in the future are appropriate. Under this general conduct standard, ISPs cannot “unreasonably interfere with or unreasonably disadvantage” (1) consumer access to lawful content, applications, and services or (2) content providers' ability to distribute lawful content, applications or services.8Until this rule was rolled back in 2017, it gave the FCC broad power to investigate ISPs it believed to be skirting paid prioritization, blocking, throttling, or transparency rules as well as engaging in “unreasonable” conduct.9

Consumer advocates argued that this general conduct standard would ensure that the FCC could prevent ISPs from finding loopholes. However, ISPs countered that the standard was ambiguously worded and would effectively allow the FCC to create new rules well beyond the scope of Congress’s original intent.

Under the current rules, there is no longer a general conduct rule. However, the Federal Trade Commission can investigate entities it believes are engaging in deceptive or misleading practices, and the FCC can investigate ISPs that are not abiding by transparency obligations.

Regulatory Framework

Behind the scenes of the consumer protections noted above is a roiling debate over the regulatory framework and legal authority that the government uses to stand up and enforce those protections. It’s important to know that net neutrality regulation is rooted in the federal laws that shape the FCC’s jurisdiction.

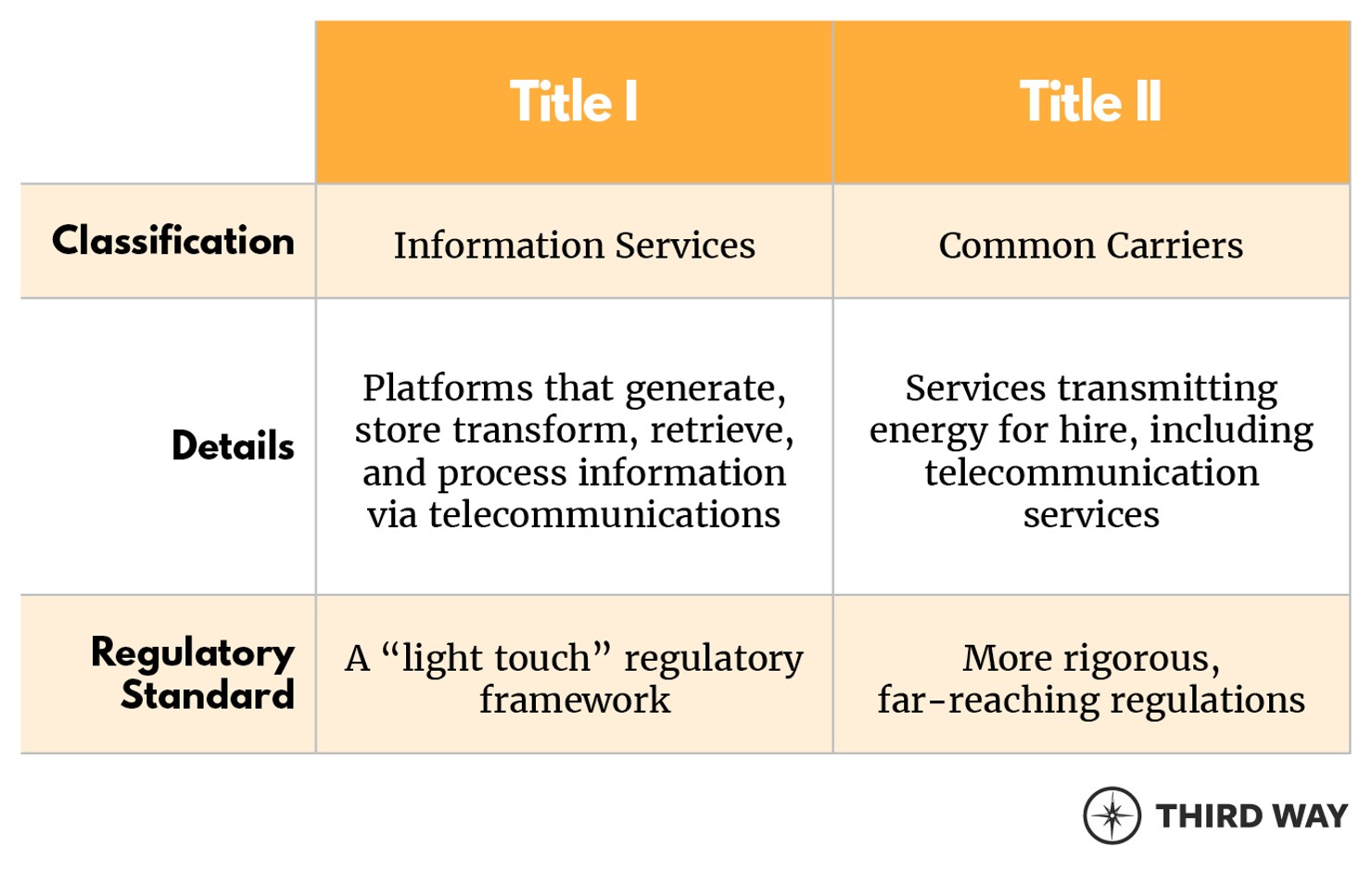

The basis of the telecommunications rules and regulatory structure began in 1934 with the creation of the FCC. Established through the Communications Act of 1934, the FCC was tasked with overseeing and regulating telephone, telegraph, and radio communications (later updated to include broadcast, cable, and satellite television).10 At the crux of today’s debate are the differences between two regulatory frameworks established by this law: Information Services (referred to as Title I) vs. Telecommunication Services (also known as Common Carrier services and referred to as Title II).

Title I of the Act defines information services as platforms that generate, store, transform, retrieve, and process information via telecommunications. Notably, this classification is often associated with a lighter form of regulatory oversight. Title II of the Act defines a common carrier as any service transmitting energy for hire, including telecommunication services.11 Common carrier regulation arose out of the regulation of railroads, whereby the government gave railroads access to the public right of way in exchange for obligations to provide access to the public. Under the common carrier designation, a service faces more rigorous regulations, most similar to telephone, gas, and electric providers.12 This includes price regulation and rules concerning the introduction of new services and the discontinuance of old ones.

The terms “information services” and “common carriers” are key to today’s net neutrality discussion. As detailed in the next section, prior to 2015, ISPs’ broadband services were classified as Title I information services. From 2015-2017, the FCC designated broadband services as Title II common carriers. Under current law, broadband service has reverted to the Title I classification that had been in effect until 2015.13

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 passed Congress with broad bipartisan consensus and brought about the first set of major changes to the original Act of 1934.14 Notably, Section 706 of the law specifically mentions the FCC’s role in encouraging reasonable and timely deployment of “advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans.”15

Since its passing, Section 706 has sparked much controversy and debate—and has been challenged multiple times in court.16 In 2010, the DC Circuit Court found that the FCC could rely on Section 706 as a source of authority to regulate and enact open internet rules.

Knowing that, unless Congress intervenes, the future of net neutrality laws rests on the previously discussed classifications: information services vs. common carriers. While the FCC has the authority to promote internet openness, the Communications Act of 1934 still prohibits certain regulations on services deemed “information services.” Settling the debate of authority has brought us to where we are now: how do we classify Internet Service Providers?

How did we get here?

Following the 1996 Act, the FCC took some initial steps classifying broadband internet access as an information service, which was upheld by the Supreme Court. However, over the last 15 years, there have been numerous twists and turns in the battle over net neutrality, largely stemming from ping-ponging regulations, court cases, and changing Administrations. Amid this, there are a few notable actions that policymakers should be aware of:

FCC 2005 Internet Policy Statement

In 2005, the FCC released an “Internet Policy Statement,” outlining the principles it expected ISPs to follow to protect consumer access to internet content. The statement marked a starting point for the next decade and a half of regulations and legal challenges that have redefined the broadband internet service industry.17

The policy included four key principles:18

- Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- Consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- Consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

It is important to note that this was not an official regulation, limiting the FCC’s ability to enforce the principles.19 In 2008, the FCC ruled that Comcast was in violation of these standards and required the company to change their practices. However, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that the FCC could not take action against Comcast because these principles were never made in an official regulation.20

FCC 2010 Order

In 2010, the FCC adopted official net neutrality rules in an Open Internet Order. Some refer to this as “Obama Plan A” since it was adopted by an FCC Chairman appointed by President Obama. The Order established rules for ISPs in hopes of creating a neutral network. Specifically, the order required transparency from internet providers and prohibited blocking and unreasonable discrimination of content.21 To monitor these rules, the FCC created an Open Internet Advisory Committee to oversee the effects of the Order and continue to build on best internet practices. In adopting these rules, the FCC retained the classification of broadband services as information services and rooted their authority to oversee ISPs in Section 706 of the 1996 Telecommunications Act.

FCC 2010 Order Court Challenges

The 2010 rules and order were appealed. In 2014, the DC Circuit Court ruled that the FCC improperly crafted the 2010 rules, arguing that the Communications Act of 1934 did not permit the specific type of regulatory oversight of information services. The court did uphold the FCC’s transparency requirements but struck down the anti-blocking and nondiscrimination rules.22

FCC 2015 Order

As a result of the 2014 court challenge, the FCC chose one course and started a new rulemaking process and reclassified broadband internet access as a telecommunications service (i.e., a Title II common carrier service). Some refer to this as “Obama Plan B” because the option was chosen by a second FCC Chair appointed by President Obama. This action exposed ISPs to the same kinds of regulation as traditional phone service, including the potential for future rate regulation and line-sharing (though the 2015 Order opted to initially abstain from these options). With this new classification and the previously established authority, the FCC regulations called for the following:23

- Reclassified broadband ISPs as common carriers

- Banned the ISPs from blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization

- Created a general conduct standard granting the FCC broad powers to protect consumers from discriminatory practices

- Enhanced existing transparency rules

The DC Circuit Court subsequently upheld the order, making these net neutrality regulations law from 2015-2017.

FCC 2017 Order

In 2017, under a new Administration, the FCC reexamined the 2015 Open Internet Order and adopted a new approach. The FCC’s new Order specifically called for a “lighter touch” on Internet regulations, restoring the classification of broadband services as information services (Title I). In short, the 2017 Order:24

- Reclassifies broadband internet access services as information services

- Allows the Federal Trade Commission to take action against any violations of terms of service or any anticompetitive acts by ISPs

- Subjects service providers to transparency requirements requiring disclosure of network management practices related to blocking, throttling and paid prioritization

- Eliminates specific FCC rules on blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization

- Reaffirms broadband as an interstate service and preempts state action that would conflict with the federal regulatory framework

Looking Ahead

Currently, multiple net neutrality advocates, consumer groups, and state Attorneys General have sued the FCC over the 2017 Order, which currently sits in the hands of the DC Circuit Court.25Simultaneously, various states have passed their own net neutrality laws banning broadband providers in their state from blocking or throttling, similar to the 2015 Order. Others have issued executive orders banning state agencies from using providers that do not uphold the net neutrality standards.26 For example:

- California passed what is referred to as the strictest net neutrality protections in the country in 2018, closely aligning with the 2015 Order. The Department of Justice immediately challenged the law and implementation has been paused as both parties wait for the decision on the Federal suit currently at the DC Circuit Court.27

- Oregon, Vermont, and Washington have enacted net neutrality legislation that prohibits blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization in their states.28

- Governors in Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, Montana, Rhode Island, and Vermont have issued executive orders stating that any internet service contracts awarded by the state will go to providers that adhere to net neutrality principles.29 Vermont’s executive order and statute have been challenged in federal court, and the state has agreed to hold off enforcement for the time being.

Both consumer advocates and ISPs want to bring back and codify protections such as no blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization—but there is disagreement over additional provisions as well as the regulatory framework to be used. Overall, the conversation surrounding net neutrality remains fluid and ever-changing. Without specific congressional action that would end the uncertainty around this issue, we will likely see the debate continue through pending legal action, ultimately coming down to three critical issues: state’s rights, the FCC’s authority, and the classification of broadband internet access providers.