Memo Published June 1, 2021 · 24 minute read

To Patch or Not to Patch: Improving the US Vulnerabilities Equities Process

Josh Kenway & Michael Garcia

Takeaways

The process that determines when and how the US government discloses unknown cybersecurity vulnerabilities to relevant companies or withholds them for government purposes lacks sufficient accountability, transparency, and public trust. Malicious actors do not hesitate to exploit “zero-day vulnerabilities,” or vulnerabilities that a company has had zero days to patch, with Chinese-based hackers most recently using a zero-day in Microsoft Exchange Servers to infect hundreds of thousands of systems.1 Yet, the government also uses zero-days to carry out activities that are in the nation’s interest and, as a result, does not tell the impacted software or hardware vendor about the vulnerability. In this case, the government determines that the benefit of not disclosing the vulnerability outweighs the consequence of a bad actor potentially exploiting the vulnerability for nefarious purposes.

In 2010, the US government created the Vulnerabilities Equities Process (VEP) to convene federal agencies that represent a range of national interests—including security, intelligence, foreign policy, commerce, and civil rights and liberties protection—to weigh distinct perspectives on how vulnerabilities should be patched or briefly kept open for law enforcement, intelligence gathering, or military purposes. However, the VEP is not codified in law and has failed to deliver greater transparency around government retention of vulnerabilities nor ensures accountability for the government’s decisions.

Congress and the Biden administration should address deficiencies with the VEP to increase transparency, strengthen accountability, build public and industry trust, and establish a world-leading model for decision-making around what to do about high-value vulnerabilities. This paper details seven steps for the Biden administration to enhance transparency and accountability in the VEP while preserving government priorities, as well as flexibility for the defense of democratic values and institutions.

The Vulnerabilities Equities Process needs better accountability, transparency, and public trust.

With malicious actors showing a willingness to exploit zero-day vulnerabilities, the US government must ensure the process to disclose or retain such vulnerabilities has transparency and accountability to facilitate public trust in the process. “Zero-day” vulnerabilities are security flaws that are unknown to the technology vendor(s) who have had zero days to patch the vulnerability but are known by a nation-state government, cybercriminal, or another third party. These actors tend to find these vulnerabilities through their own due diligence or by purchasing them from an actor or business that discovers and sells vulnerabilities (i.e., vulnerability sellers). These vulnerabilities then allow a range of good and bad actors to access or disrupt otherwise well-secured systems and networks.

If governments identify zero-days, the timely disclosure of those flaws to vendors can enable the development and release of patches or other fixes before malicious actors discover those vulnerabilities.

For example, cybercriminals may use zero-days to deploy hard-to-stop malware that advances their financial interests, while authoritarian governments may use them to surveil their citizenry. For instance, in 2017, the Russian government exploited a zero-day vulnerability to launch the NotPetya ransomware, which forced global companies like Fed-Ex and Merck to shutter their businesses, costing them millions of dollars.2 Conversely, these vulnerabilities may help law enforcement agencies, intelligence agencies, or military entities within democratic governments to collect information about security threats or advance goals that are in their national interest.

The US government weighs the risks and benefits of disclosure and retention through a complex process and decisions are often made under a significant degree of uncertainty (e.g., as to whether a malicious actor also knows about a vulnerability). Crucially, any process that a government in a liberal-democratic system adopts to make such decisions should advance core values of transparency, accountability, and public trust by ensuring the consideration of a wide range of elements that make up the national interest. These so-called “equities” include typical national security interests, such as intelligence visibility, military operational capabilities, critical infrastructure protection, criminal justice, and overall economic output. However, the disclosure or retention decision must extend past traditional national security interests by including consideration of civil rights and liberties protections (including online privacy and data protection), as well as the cybersecurity and competitive interests of private-sector organizations. The inclusion of these equities helps advance the collective interest of the US government and, in turn, the American people.

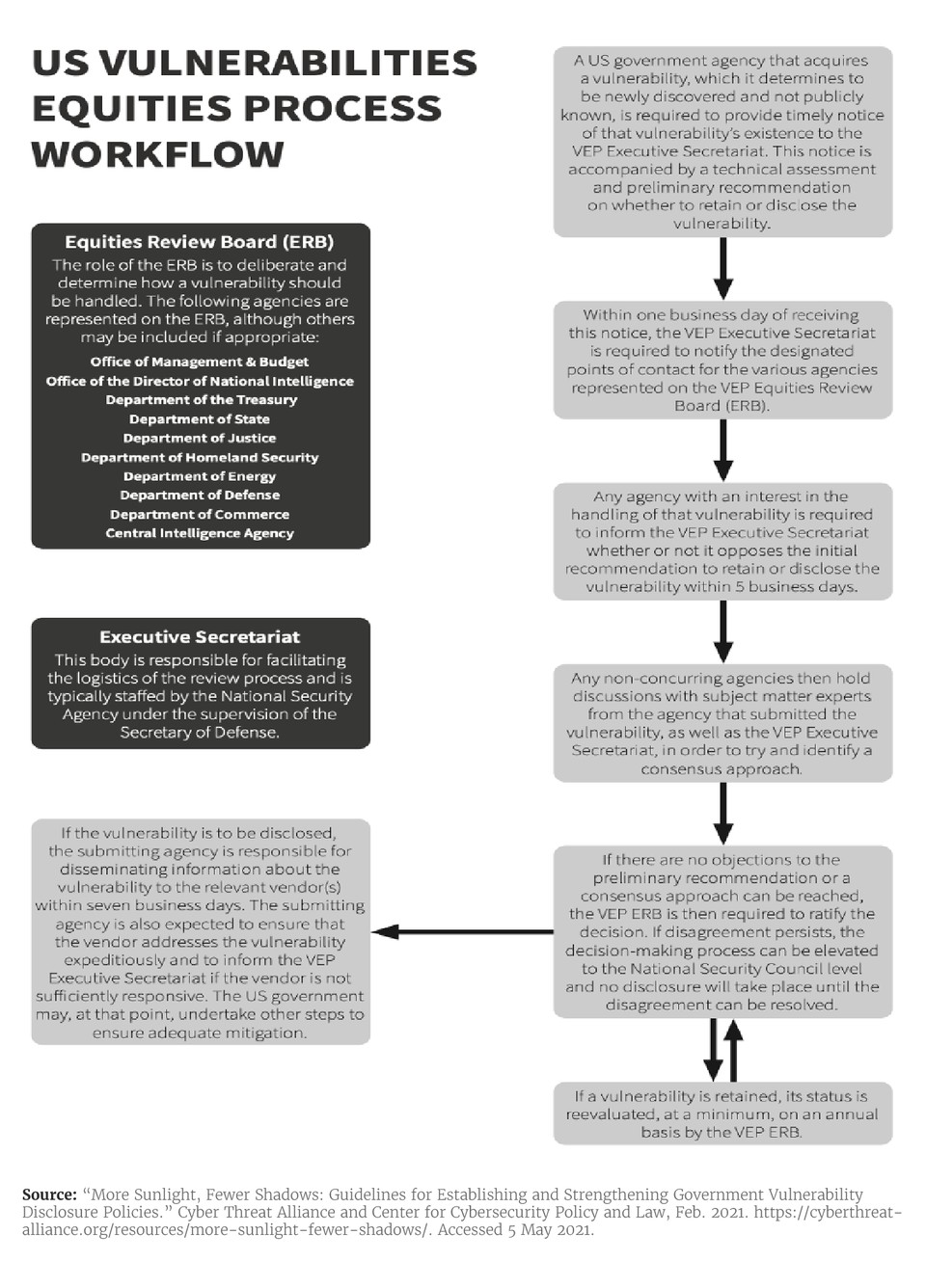

The US government created the VEP in 2010 as an internal mechanism at the National Security Agency (NSA) to convene federal agencies to discuss what to do with zero-days affecting software or hardware.3 This process gradually evolved through the Bush and Obama administrations into an inter-agency vehicle for regularized deliberation of zero-day decisions.4 Its current workflow, according to the Cyber Threat Alliance and Center for Cybersecurity Policy & Law, is summarized below.5

Vulnerabilities Equities Process (VEP) vs. Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure (CVD)

The VEP’s mechanisms are separate from the Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure (CVD) policies that government organizations have adopted over recent years. CVD processes allow security researchers to report security flaws in government IT systems to the relevant federal agencies without fear of reprisal for “hacking” into a government system. These disclosures are excluded from the VEP and are subject to their own disclosure regime.6

While the US VEP is recognized to be the most mature and deliberative process of its kind globally, it still falls short in delivering on some of its most essential goals. These include providing transparency, enabling accountability, ensuring public and industry trust, and elevating voices from outside the traditionally defined national security community in cyber policy decision-making. The Biden administration and Congress should therefore take steps to implement the following recommendations to address current challenges with the VEP.

Recommendation #1: Expanding unclassified and classified reporting on VEP throughput and process

Problem

The government has not disclosed unclassified, public information on VEP decisions despite a requirement in the existing framework. This shortcoming has impeded congressional and public scrutiny and diminished trust in the VEP.

The “VEP Charter,” released in 2017, details how the VEP operates and requires the Executive Secretariat to “produce an annual report … written at the lowest classification level permissible.”7 While the full report can be classified and its transmission to Congress an option rather than a requirement, the charter stipulates that “at a minimum, [the inclusion of] an executive summary written at an unclassified level.” No such summaries have been released to date. Nor has Congress — beyond closed-door sessions of the House and Senate Select Committees on Intelligence — been able to scrutinize the classified details of VEP decisions.8 In its present state, the transparency supposedly assured under the VEP is largely illusory.

While skeptics would be concerned that US adversaries could use information released in a public report that describes an aspect of US cyber capabilities, the US government has balanced transparency and accountability with national security interests in other contexts. For example, the National Intelligence Priorities Framework (NIPF) annually articulates intelligence-gathering priorities, but “while the NIPF itself is classified, much of it is reflected annually in the [Director of National Intelligence’s] unclassified Worldwide Threat Assessment.”9 Similarly, the US government is required to disclose aggregate figures for the number of otherwise classified National Security Letters—letters law enforcement and intelligence agencies issue to private institutions during highly sensitive investigations—as well as the number of requests covered by those letters.10

Solution

The Biden administration should increase the volume and usefulness of information that is publicly disclosed about the VEP’s inner workings. The Administration should release similar information retroactively for years where public reporting was required under the VEP’s governing framework. The ERB should also provide a classified assessment on the VEP’s processes for relevant Congressional committees and policymakers.

Specifically, the Biden administration should ensure this disclosure occurs annually and publicly release unclassified executive summaries from 2017 through 2020. Such transparency would be a positive step towards restoring overall confidence in the VEP and motivating wider political re-engagement on prospective reforms. The Biden administration should also continue releasing these summaries irrespective of whether broader VEP reform takes place through legislation and/or Executive Order. These actions would establish a norm for future administrations to either adhere to or risk facing political consequences for breaking the set norm.

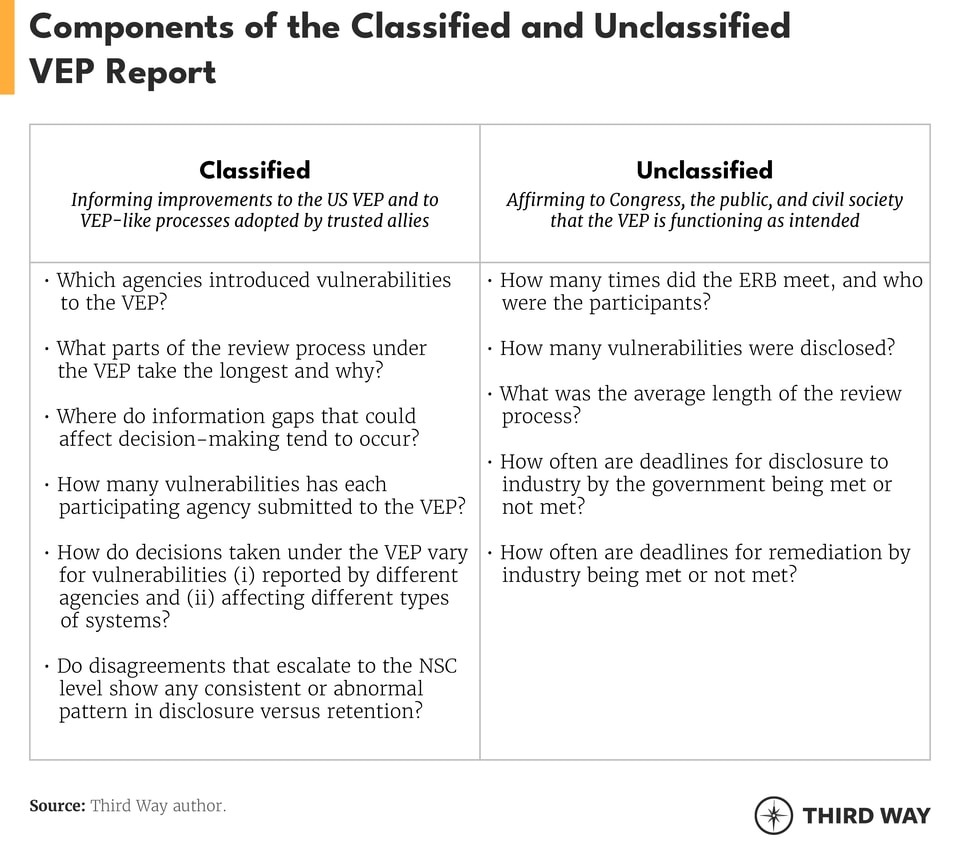

In addition to information relevant to ensuring congressional accountability, classified reporting should include analysis that could inform future improvements to the VEP and similar processes adopted by international allies and partners. Unclassified reporting, in contrast, should serve to affirm to Congress, the general public, and civil society organizations that the VEP is functioning as intended. Outside of the annual reporting framework, and especially given that the VEP “is a relatively new process that addresses a dynamic problem,” the Biden administration should also aim to be as transparent as possible around future procedural changes to the VEP.11

The following considerations should be addressed in the scope of classified and unclassified annual reporting:12

Recommendation #2: Transferring coordinating functions for the VEP (i.e., it's Executive Secretariat) from the NSA to the Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD).

Problem

With the VEP’s Executive Secretariat operating under the NSA, several organizations and former federal officials have raised concerns that the VEP may be more easily manipulated or circumvented by offense-oriented interests within the government.13

Since the NSA currently houses the VEP Executive Secretariat, which manages various aspects of the process, critics assert that security and intelligence agencies can manipulate the VEP to serve their interests. There is little, public evidence to substantiate speculation that law enforcement, intelligence, or military entities are empowered to circumvent, delay, or otherwise impede the stated goals of the process. However, such risk — particularly under a less transparent, more reckless administration — is nontrivial. Further, the failure of the Executive Secretariat to publicly release the required unclassified executive summaries of annual reports on VEP outputs in recent years fuels these concerns (see Recommendation #1).

Solution

With the support of staff from CISA, NSA, and other agencies, the ONCD would be better positioned to house the coordinating functions and ensure accountability for the VEP given its mandate to engage on a wide range of cybersecurity issues.

Because the White House can freely change the agency responsible for housing the Executive Secretariat, the Biden administration should look to make this change ahead of any Congressional action. Congress should then enumerate this role through legislation to prevent a potential policy reversal under future administrations and appropriate sufficient resources to the ONCD to fulfill these duties. An ONCD-based Executive Secretariat would also be well-positioned to identify and engage ad hoc participants for the ERB.

Recommendation #3: Clarifying responsibilities and processes after a decision to disclose has been made

Problem

Currently, agencies that discover or acquire zero-day vulnerabilities are responsible for disclosing that information to the relevant vendor(s), even when they may not be the best agency to make the disclosure. The VEP also does not detail follow-on actions that disclosing agencies should take when a vendor(s) fails to fix disclosed vulnerabilities.

If the ERB decides that a vulnerability should be disclosed, the agency that discovered or purchased that vulnerability is responsible for disclosing it to the vendor, unless they choose to nominate an alternative agency to perform that notification.14 However, security and intelligence agencies are both more likely to submit vulnerabilities to the VEP and may not always have pre-existing relationships with certain vendors.

Moreover, vendor notification is currently required to be “expeditious” but no obligation exists to meet the stated goal of notifying vendors within seven business days of deciding to disclose a vulnerability or any other concrete deadline.15 Additionally, no data publicly exists on the timeliness of industry responses to disclosures. If vendors are not responsive to the disclosure or fail to address the vulnerability, then the VEP Charter suggests that the US government may take other steps to mitigate the vulnerability. However, in failing to specify what that means, the government is leaving vendors and end-users in the dark. These flaws in the VEP’s disclosure and follow-on processes risk jeopardizing a core VEP policy objective — ensuring successful disclosures that strengthen cybersecurity for end-users.

Solution

The Biden administration should establish and publicize policies so that disclosures are timely; allow the most appropriate agency to deliver the disclosure notification, which should by default be CISA; and develop policies for when vendors do not respond swiftly to a disclosure.

First, the Administration should establish hard deadlines for initial, government disclosures to vendors. The White House could require vendor notification to take place within 14 business days of an ERB decision, or within 48 hours for vulnerabilities that nation-state adversaries or cybercriminals are actively exploiting. The Administration should also promote greater transparency with the public around whether these deadlines are being met (see Recommendation #1).

Second, VEP disclosures should, by default, come from a single point of contact housed within a trusted, defense-oriented agency that already liaises regularly with the private sector. By making disclosures through a single point of contact, the process can emphasize consistency, reliability, and repeatability. CISA is the obvious choice. Some flexibility, however, should be preserved such that dialogue between CISA and other agencies can ensure a consistently best-case disclosure approach.16

Third, members of the ERB should consult with private partners to develop a transparent and routine approach for post-disclosure, government activities for when a notified party does not patch a vulnerability or does not do so promptly. This process should be developed based on classified and unclassified data on how often vendors patch disclosed vulnerabilities, the average time it takes to patch a vulnerability, and government actions taken in the past to address private sector vulnerabilities.17 Creating this process with private partners will eliminate ambiguity on when the government acts to take additional post-disclosure steps, how they will act, and under which authorities.

Recommendation #4: Ending the use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) with vulnerability sellers

Problem

A loophole in the VEP allows entities that sell zero-day vulnerabilities to federal agencies to use NDAs that limit the US government’s ability to disclose purchased vulnerabilities to affected vendors.

When a federal agency procures a zero-day vulnerability from a third-party seller, such as a vulnerability broker or offense-oriented research organization, these entities can use NDAs to limit what the federal government can do with the vulnerability information exchanged—including limiting disclosure. The “Exceptions” clause of the VEP Charter acknowledges that a “decision to disclose or restrict vulnerability information could be subject to restrictions by partner agreements.”18 While it is unclear how often these NDAs are signed, the existence of this loophole undercuts the stated purpose of the VEP and reduces trust in the process.

Solution

Congress or the Biden administration should close the VEP’s NDA loophole; a change that has the support of both civil liberties advocates and key former US government officials.19

The US government should establish policies barring zero-day procurement arrangements between the government and third parties that would limit the potential for VEP disclosures. However, as the VEP and international equivalents become more transparent, robust, and accountable, private-sector offerings of “access” to technology or “extraction” of data—some of which use zero-day vulnerabilities—could continue to spread more widely than under the status quo. Under these companies’ contracts, neither vulnerabilities nor exploit code are shared, so governments that contract for these services have nothing substantive to disclose to the affected vendor.20 A recent report from the Atlantic Council highlights several policy recommendations for addressing concerns around the global proliferation of these services. These measures include “accelerating [VEP] decisions” for vulnerabilities being exploited by companies who exfiltrate data.21 However, aside from this action, the VEP is not the best process to push either consideration or implementation of constraints on these types of companies. Further discussion of this issue about the VEP and the longstanding encryption debate can be found in Appendix A.

In contrast, when US allies share vulnerabilities, their requests for non-disclosure should continue to be respected to protect those diplomatic ties and support forward-looking reciprocity in handling vulnerabilities that underlie critical offensive cyber capabilities. This also underscores the need for allies and partners to adopt VEP-like processes that consider international relationships in decision-making (see Recommendation #7).

Recommendation #5: Reinforcing the consideration of civilian privacy and civil liberties interests in the VEP

Problem

Privacy and other civil liberties interests are not adequately represented on the ERB. Further, a perception exists that offensive-oriented interests are favored when policy disagreements move to the NSC.

Despite having a goal to “prioritize the public’s interest in cybersecurity” when deciding to retain or disclose a vulnerability, the VEP does not adequately ensure consideration of civilian privacy and civil liberties interests.22 Additionally, the fact that disagreements at the ERB level are escalated to the NSC process creates a perception that offense-oriented agencies who may favor retention over disclosure are at a procedural advantage.

Solution

The Biden administration should identify and add to the ERB federal entities that are motivated and capable of advocating for privacy and civil liberties interests. The Administration should also work to address perceptions that escalating disagreements to the NSC favors offense-oriented interests.

The addition of one or more participants to the ERB who focus on protecting civilian privacy, data protection, and other civil liberties interests would improve deliberations on these issues. Adding privacy and civil liberties-oriented agencies, like DOJ’s Office of Privacy and Civil Liberties and the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, would be a good first start. These entities would be well-equipped to provide subject matter expertise and articulate relevant concerns to other ERB participants. However, bureaucratic challenges may restrain their long-term effectiveness on the ERB.23 Therefore, if the VEP is placed under the ONCD, the Administration should establish a deputy within the ONCD who could tackle all issues related to privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties and serve on the ERB.

Further, this paper does not oppose the continued escalation of disagreements at the ERB level to the NSC process. In fact, the NSC process provides some degree of political accountability that serves as a check against unacceptably high-risk retention decisions. Additionally, few other mechanisms for escalating and resolving inter-agency policy divisions exist in a mature and regularized forum within the Executive Branch. Moreover, the clearest alternative to the current approach — providing a single agency off-ramp to resolve disagreements — would run counter to the collaborative, holistic decision-making philosophy that lies at the heart of the VEP.

Yet, addressing concerns that offensive-oriented interests are put at an advantage compared to defensive-oriented interests must be addressed. Therefore, the Biden administration should adopt other reforms that enhance transparency and accountability for the VEP to address concerns about this arrangement. As the role and functions of the ONCD become clearer, the Biden administration may wish to revisit whether the NSC remains the best vehicle for escalating decision-making under the VEP or whether the ONCD could provide a more effective and neutral venue for such deliberations.

Recommendation #6: Working with the US Congress towards a narrow legislative codification of the VEP

Problem

Currently, the executive branch retains full discretion over how the VEP functions, including whether to adhere to expectations around transparency and accountability. Previous Congressional efforts to codify the VEP, however, have over-extended in some areas while failing to deliver in others.

A group of bipartisan legislators introduced Protecting Our Ability to Counter Hacking (PATCH) Act (HR 2481) in 2017 to establish legislative oversight procedures and executive branch obligations for the VEP.24 This bill would have advanced several positive reforms to the VEP, such as:

- Formalizing the ERB;

- Requiring the distribution of an unclassified process description to Congress;

- Requiring the ERB to submit annual reports to the PCLOB and relevant congressional committees;25

- Requiring the release of an unclassified, public version of those reports;

- Mandating that DHS disclose vulnerabilities to the relevant vendor(s), rather than the agency that submitted the vulnerability to the VEP;

- Empowering DHS to establish and supervise procedures for disclosure.

However, the PATCH Act also had some shortcomings:

- Failing to provide financial resources for the implementation of the revised VEP;

- Failing to ensure permanent representation on the ERB for the Departments of State, Treasury, Energy, or the FTC;

- Preventing ERB participation for agencies not included on the NSC, but who may have an occasional interest in the handling of certain vulnerabilities (e.g., Department of Agriculture, Department of Transportation).

Solution

The Biden administration should work with Congress to codify the VEP to implement transparency and accountability reforms, while allowing the executive branch to retain flexibility on procedural details.

The Biden administration should work closely with Congress to codify the VEP, while addressing the shortcomings in the 2017 PATCH Act. A bill codifying the VEP should include:

- Requiring the ERB to produce and release classified annual reports to appropriate congressional committees and an unclassified, public report to promote transparency (see Recommendation #1);

- Requiring the ERB to provide classified updates on changes to the VEP to appropriate congressional committees and, when feasible, an unclassified, public update (see Recommendation #1);

- Placing the Executive Secretariat function of the VEP under the ONCD (see Recommendation #2);

- Empowering the ONCD-based Executive Secretariat to identify and engage ad-hoc ERB participants on a case-by-case basis (see Recommendation #2);

- Appropriating adequate funds for the VEP (see Recommendation #2);

- Barring executive branch agencies from signing NDAs when purchasing vulnerabilities (see Recommendation #4).

- Placing responsibility for identification of ERB permanent participants with the President.

Any legislation should ensure that the executive branch has the flexibility to shape the process at a more granular level. For example, the White House should retain control over the process that determines which equities are articulated and weighed given changes in the cyber-risk landscape, as well as shifting foreign and domestic policy priorities. Similarly, flexibility should be retained for changes to disclosure processes and expected remediation timelines, given that relevant best practices may change over time and also vary across types of vulnerabilities in different technologies (see Recommendation #3). Lastly, the White House should retain the ability to include agencies on the ERB and develop processes for escalating disagreements within the VEP (see Recommendation #5).

Recommendation #7: Advocating for more widespread international adoption of VEP-like processes

Problem

While Canada and the United Kingdom have publicly adopted processes similar to the VEP, widespread adoption of VEP-like processes by international allies and partners has not occurred.

With decisions around other governments’ vulnerability retention and exploitation practices being made outside of transparent, holistic, and accountable mechanisms, there is greater potential for bad decision-making or procedural abuse by security agencies. Moreover, without harmonized processes, the potential benefit of sharing insights about decision-making considerations among allies and partners is reduced. For governments that have adopted these kinds of processes, including the US government, sharing vulnerability information with non-adopters also risks potential mishandling or misuse of that information.

Solution

The Biden administration should push allies and partners to adopt VEP-like processes that adhere to a best practice approach of convening government stakeholders encompassing a common set of equities. These processes should enforce public transparency and establish both political and legislative accountability.

Alongside efforts to reinvigorate the US VEP and strengthen its assurances of transparency and accountability, the Biden administration should push partners, allies, and competitors alike to establish similar processes. The Cyber Threat Alliance and the Center for Cybersecurity and Policy and Law articulate guidelines that US policymakers should consider when working with nation-states to adopt their own VEP framework.26

Information about zero-day vulnerabilities retained under harmonized VEP-like processes, as well as associated analysis that informed decisions to retain, could be more safely and regularly shared with close allies who adopt these processes. Sharing vulnerability information and related insights with allies and partners could in turn help to drive better decision-making in the future, given the high level of uncertainty that factors into retention-disclosure decisions (e.g., “Are adversaries currently exploiting this vulnerability in the wild?”). In addition, greater global transparency around VEP decision-making would help to advance the establishment of norms around the development and use of tools for cyber conflict.

Conclusion

While often not discussed as a cybersecurity policy challenge to resolve, reforming the VEP to enhance transparency, accountability, and public trust is a critical piece to the overall US government’s cybersecurity strategy. At its core, the VEP decides whether the government preferences cyber defense or offense, which has massive societal implications. While these decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis, illuminating how those decisions are made and including more diverse voices into those decisions will help ensure that all American’s equities are considered.

Appendix A: Contextualizing The “Access” Debate

As referenced in Recommendation #4 on ending the use of NDAs with vulnerability sellers, emerging markets for “access” and “data extraction” services threaten the viability of the VEP as a means of ensuring accountability and promoting transparency for governmental hacking. These services also “speed and scale up the ability of foreign governments to conduct offensive cyber operations” and, as such, a more robust global dialogue is needed around potentially limiting their use to prevent harmful deployment and to limit their broader role in advancing the cyber capabilities of authoritarian governments.27 However, a discussion of such limitations intersects with a broader debate around how democratic governments might lawfully access data or systems specifically during law enforcement investigations. In this context, distinct civil liberties interests come into conflict in ways that demand nuanced discussion.

Preserving public access to strong communications encryption while avoiding a situation in which communications relevant to ongoing law enforcement investigations become entirely impenetrable to government scrutiny demands a careful regulatory balancing act. DHS’s Public-Private Analytic Exchange Program (AEP) noted that “end-to-end encryption (E2EE) precludes access to the full content [of data in-transit] even if granted unilateral access by the messaging service provider in compliance with a lawful order.”28 In other words, communications that are end-to-end encrypted are largely impenetrable to law enforcement services in real-time. However, the architecture of E2EE that causes this impenetrability is also critical to secure communications among government and private sector organizations, as well as the general public. Such an assurance of inscrutability is key to upholding basic cybersecurity tenets of confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity. However, this situation leaves only at-rest devices or data (e.g., in cloud backups) as potential entry points for lawful access by governments.

Third Way and the authors of this paper believe firmly that (A) the general public’s right to use encrypted communication technology should not be infringed (e.g., through the creation of “backdoors” to encrypted communication technologies), and (B) that criminal offenses of comparable severity to those mentioned above pose a serious, material threat to global democracy and the aspiration of equal justice under law. Moreover, as articulated previously, Third Way supports allocating more resources and providing additional training for law enforcement “in identifying, collecting, and using digital evidence that is legally available to them.”29

However, access and data extraction services also have a legitimate role to play in the pursuit of the aforementioned objectives. Excessive constraints on law enforcement’s ability to access data-at-rest on devices without lawfully accessible cloud backups would hamstring efforts to tackle serious, organized crime such as money laundering, government corruption, and violent extremism, which have flourished in the digital age. This kind of access does not necessarily require the exploitation of zero-day cybersecurity vulnerabilities, for example, for unlocked devices or devices with out-of-date operating systems. However, in some instances, this access may need to be achieved through exploitation of zero-days either directly by federal law enforcement, which would implicate the VEP, or indirectly through certain access offerings from the private sector.

As such, while the specter of ‘government hacking’ under either approach demands close scrutiny and meaningful accountability, it is also a necessity if we are to preserve public access to encryption and tackle serious, cyber-enabled crime. The United States needs more and better mechanisms in the vein of the VEP, alongside well-designed regulations that constrain the circumstances and methods under which government agencies may make use of those access or data extraction services that are suspected of leveraging zero-day vulnerabilities. Governments should pay more attention to how access to data or systems is best achieved across different agencies, operational goals, and levels of government. Moreover, fulsome consideration of these trade-offs will be crucial in generating the kind of informed engagement among relevant stakeholders that is needed to shape these mechanisms and constraints most effectively. As with so many policy challenges associated with digital technology, there is no easy, perfect solution here; only trade-offs that require a thoughtful approach and demand baselines of transparency and accountability.