Memo Published February 4, 2022 · 9 minute read

Protect Workers’ Health Care with the Build Back Better Act’s Cost Caps

David Kendall & Ladan Ahmadi

Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all agree on one thing: cost is their top health care concern.1 Congress can quickly address that concern by ensuring that however the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) evolves and moves forward, it continues to cap health care costs for America’s workers. A cost cap consists of limits on premiums and out-of-pocket costs based on income. There were three specific cost caps in the House-passed BBBA that are critical to maintain as the Senate looks to move the legislation forward: 1) extend the cap on premium costs for all workers who receive coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges; 2) lower the cost cap on premiums for coverage through medium and large employers; and 3) cap costs for low-income workers who live in states that have not expanded coverage through Medicaid.

Workers need permanent protection from high health care costs through a cost cap so that health care is affordable for their budget and does not lead to bankruptcy. The cost cap provisions in the House-passed bill build toward a universal cost cap while preserving the various ways that Americans get health insurance, including through employment-based coverage. In this memo, we examine how the BBBA provisions caps costs for workers, maintains and improves employment-based coverage, and is a model for future reforms.

Three Ways to Cap Costs for Workers

The three cost cap provisions in the House-passed BBBA are centered on ensuring workers can afford health coverage. Specifically, they would:

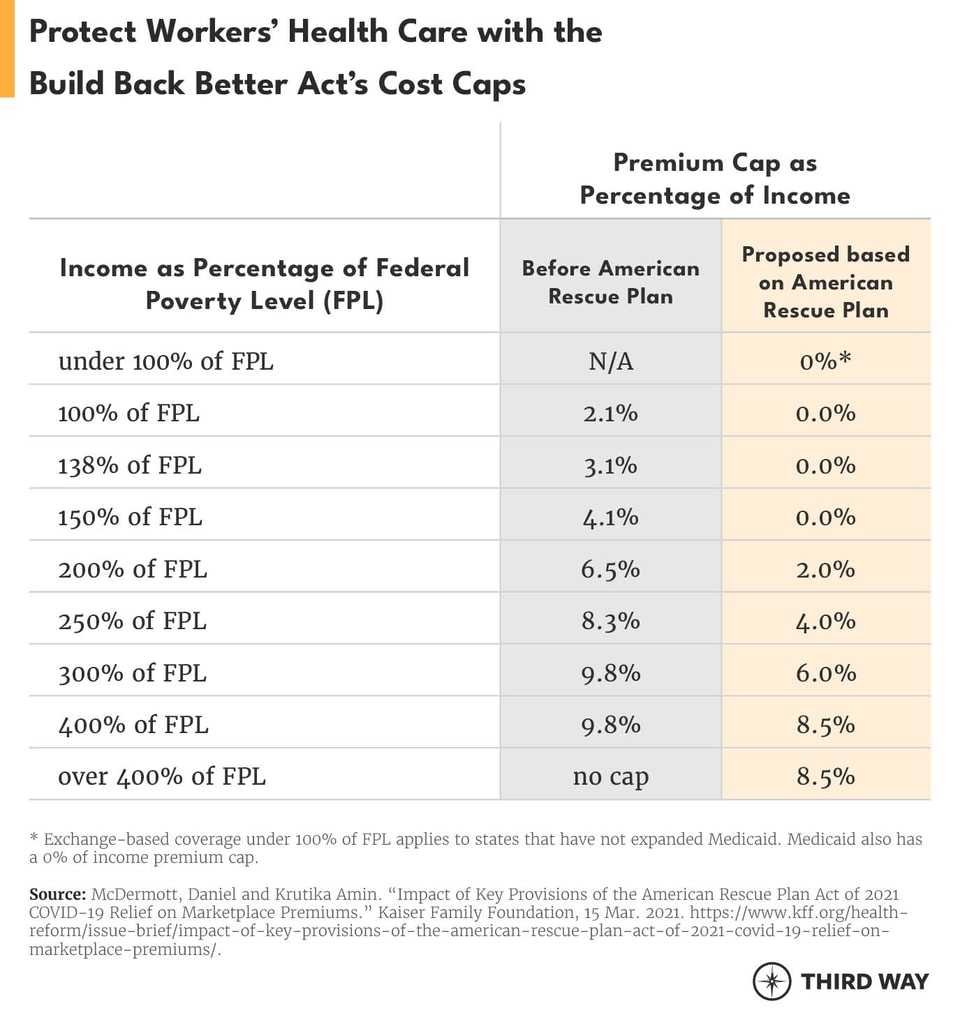

1. Extend caps on premiums for workers and their families with exchange-based coverage. This provision would extend the Affordable Care Act (ACA) cost cap included in the American Rescue Plan through 2025. The cost cap lowers the premiums people in the exchanges pay based on their incomes. For example, it cuts the cost of premiums by two-thirds for workers with exchange-based coverage and an income of $25,760 (200% of the federal poverty level). Before the American Rescue Plan, people earning more than four times the federal poverty level had no cap on their premiums. As the chart below shows, everyone in the exchanges can get affordable coverage based on premiums that fit their family’s income. This cost cap would expand coverage for 1.2 million people who today cannot afford any coverage.2

2. Lower the cap on premiums for workers with employment-based coverage. Employers with 50 or more employees will be required to ensure that their employees don’t pay more than 8.5% of their income on health insurance premiums. Under current law, medium and large employers face a penalty if their employees end up getting financial assistance through exchange-based coverage because their employer coverage did not meet the affordability standard. Currently, the affordability standard states that premiums can’t exceed 9.6% of a workers’ wages. The new, lower cap could save an employee with an average income as much as $739 a year.3

3. Cap costs for low-income workers. Workers with poverty-level incomes who live in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid as provided in the ACA will have a cap on their premiums and out-of-pocket costs for four years, starting in 2022.4 These low-income workers with incomes under 100% of the Federal Poverty Level will be eligible for coverage through the federal health insurance exchange, HealthCare.gov. They will have access to comprehensive coverage based on their income—regardless of whether their employer provides it—just as low-income workers have today in states that have expanded Medicaid.5 It will help reduce a major health care inequity, which leaves 51% of Black people, 28% of Hispanic people, 11% of Asian/Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people, and 22% of American Indian and Alaska Native people uninsured compared to 11% of white people who are non-elderly in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid.6 Overall, this BBBA provision would lower the number of people without any coverage by 1.7 million.7

Improving Employment-Based Coverage

The health care provisions from the House-passed BBBA are essential for workers. And while the national debate has focused on changes to the ACA and Medicaid, improvements to employment-based coverage shouldn’t be overlooked. They not only preserve the employment-based insurance system in the country, which more than half the population relies on, they also strengthen it in two ways.

First, the BBBA provision to lower the cap on premiums would make coverage more affordable for employees at medium and large employers. Right now, employers with many low-wage workers are 20% less likely to see their employees sign up for coverage.8 For workers at those firms that do enroll, an employee earning poverty-level wages faces an average premium that is 12% of their income for coverage of just themselves.9 A lower premium cap would encourage employers to make coverage more affordable through innovative benefit design that pegs premiums to income while giving employees assurance their coverage will be more affordable.

Coverage in the states that have not expanded Medicaid has a side benefit of making coverage more affordable for employers with low-income employees.

Second, the BBBA provision for coverage in the states that have not expanded Medicaid has a side benefit of making coverage more affordable for employers with low-income employees. Employers in states that have expanded Medicaid have already benefitted from Medicaid expansion. Federal rules give employees the opportunity to have Medicaid coverage because it can be more generous than what their employer may be able to afford. For example, in the three years after states began to expand Medicaid, the number of employees with Medicaid working at small businesses (under 100 employers) grew by 50% from 5.1 million employees to 7.6 million employees.10 As a result, one-in-seven small business employees is enrolled in Medicaid coverage.11 At the same time, Medicaid expansion did not cause small employers to stop offering their own coverage.12 The BBBA provision gives low-income employees the same opportunity to enroll in exchange coverage as they would have for Medicaid if their state had expanded it and lowers employers’ costs for those employees.13

Looking Ahead

While our hope is that a version of the House-passed BBBA can move through the Senate and become law, other gaps remain and will have to be dealt with in the months and years ahead. Here are three areas where additional cost caps can help America’s workers:

- Cap premiums for families with employment-based coverage. The cap on premiums for employment-based coverage, which a BBBA provision lowers to 8.5% of income, benefits individual employees—not their families. This problem, known as the family glitch, arose during the implementation of the ACA.14 One solution is to change ACA regulations so the premium cap for employees extends to family premiums.15 That would allow a spouse and children of employees to seek coverage through the exchanges when employment-based coverage is not capped to an affordable level for them. Medium and large employers (with 50 or more employees) would not face a penalty when an employee’s dependents get affordable coverage through the exchanges.

- Cap costs for low- and middle-income employees. Employers with a large portion of low-wage workers typically have less generous coverage than employers with more higher-wage workers. For example, lower-wage employers offer an average deductible of $1,693 for single coverage compared to $1,467 among employers with higher-wage employees. A similar problem is that employers with more low-wage workers require employees to pay an average of 35% of family premiums compared to 24% for employers with higher-wage workers. Simply put: the public financing for employment-based coverage is regressive. Employees with job-based coverage receive financial assistance through a tax law that excludes their health benefits from income and payroll taxes. The value of the tax exclusion to employees depends on the employee’s tax rate for income and payroll taxes. It is regressive because the lower their tax rate, the less assistance they receive. The highest earning 20% of taxpayers receive 44% of the tax relief from the income tax exclusion.16 In contrast, workers in exchange-based coverage receive a tax credit that is worth more at lower incomes. For example, the tax credit for a worker earning $32,200 (250% of the federal poverty level) is worth $2,363 more than the value of the tax exclusion for the employer and employee shares of the premiums for employment-based coverage.17 One way to fix this problem is to allow employers to use a version of the ACA’s tax credits to supplement the benefits of low-to-middle income employees.18 Cost caps for low- and middle-income employees would make the public financing for employment-based coverage less regressive. To offset additional federal costs for this cost cap, Congress should stop the many ways health care nickel and dimes patients through multiple bills, excessive prices, and wasteful care.19

- Cap costs for those battling chronic conditions. People with chronic or severe health conditions often face a lengthy struggle to afford the care they need. Too often, they can be devasted financially despite having health care coverage. They need more generous coverage when they pay a high share of their income on out-of-pocket health care costs for more than one year in a row. For example, someone with high expenses who would normally get a silver-level plan in the exchanges should qualify in the following year for a tax credit pegged to the cost of a gold-level plan, which covers a greater portion of out-of-pocket costs. Such an approach mirrors how the cost cap provisions direct assistance for people in states that have not expanded Medicaid.

Cost caps for low- and middle-income employees would make the public financing for employment-based coverage less regressive.

Conclusion

The cost cap provisions from the House-passed BBBA are driving toward a universal cost cap, which would be available to all—no matter their existing source of coverage.20 Not only does the BBBA expand cost caps for workers, it also caps drug costs for older and disabled Americans through Medicare. And it continues a cost cap for people receiving unemployment through exchange-based coverage, a measure that was first enacted in the American Rescue Plan. Together, these provisions point toward a day when no one in America need worry about the high cost of health care.