Memo Published February 27, 2023 · 7 minute read

On to the Next: Where a Closed Accreditor's Schools Are Now

Chazz Robinson & Shelbe Klebs

The Biden Administration and the US Department of Education (Department) have shown their desire to put accreditors in the hot seat and ensure they’re fulfilling their quality assurance mission. Recent actions the Department has taken include reinstating the accreditor dashboards, combating “accreditor shopping” through new guidance, and revising the Accreditation Handbook to clarify agency expectations for student achievement metrics.1

Each of these steps is intended to strengthen the accreditation process and uphold the important role accreditors play in protecting students and taxpayers. But these actions pale in comparison to the monumental decision the Department made last year to terminate federal recognition of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS).2 ACICS was an embattled accreditor with a notorious track record for failing its oversight duties, culminating in the collapse of Corinthian Colleges and ITT Technical Institute. Now that it’s been officially ousted as a gatekeeper of federal dollars, it leaves us wondering: where will the schools formerly accredited by ACICS go to seek new approval, and is there a new bottom-of-the-barrel accreditor on the horizon?

The 411 on ACICS

ACICS was previously one of the larger college accreditors with around 300 schools in its portfolio as of 2016, most of which were for-profit colleges. That year, it was terminated by the Obama Administration for failing in its oversight duties of Corinthian and ITT Tech; ACICS had continued to accredit the schools despite findings of rampant fraud and abuse. Despite these troubles, the Trump Administration gave ACICS a second chance and reinstated the agency in 2018, giving it one year to improve or face termination again. ACICS couldn’t turn it around and fell under Department investigation again in 2021. Finally, in 2022, the Department officially stripped ACICS of its federal recognition, rejecting its appeal and leaving its remaining institutions 18 months to find new accreditor homes.

Experts were unsurprised to see ACICS lose its gatekeeper status given its poor track record: between its first and second terminations, only 30% of students at ACICS schools earned more than the average high school graduate and nearly 75% had either defaulted on their student loans or failed to pay down $1 on their principal within three years of attending.3 Institutions saw the writing on the wall, too—when the Department stripped ACICS of recognition in 2016, it accredited 237 schools, but by the time it lost recognition again in 2022, just 27 institutions remained.4

Those few remaining colleges now need to find a new accreditor willing to take them. Knowing that ACICS was truly bottom of the barrel when it came to holding institutions to high standards of quality, we wanted to see where its schools landed between its time of reinstatement in 2018 and final loss of recognition in 2022 and examine what that means for the accreditation space.

To Which Accreditors Did Former ACICS Schools Move?

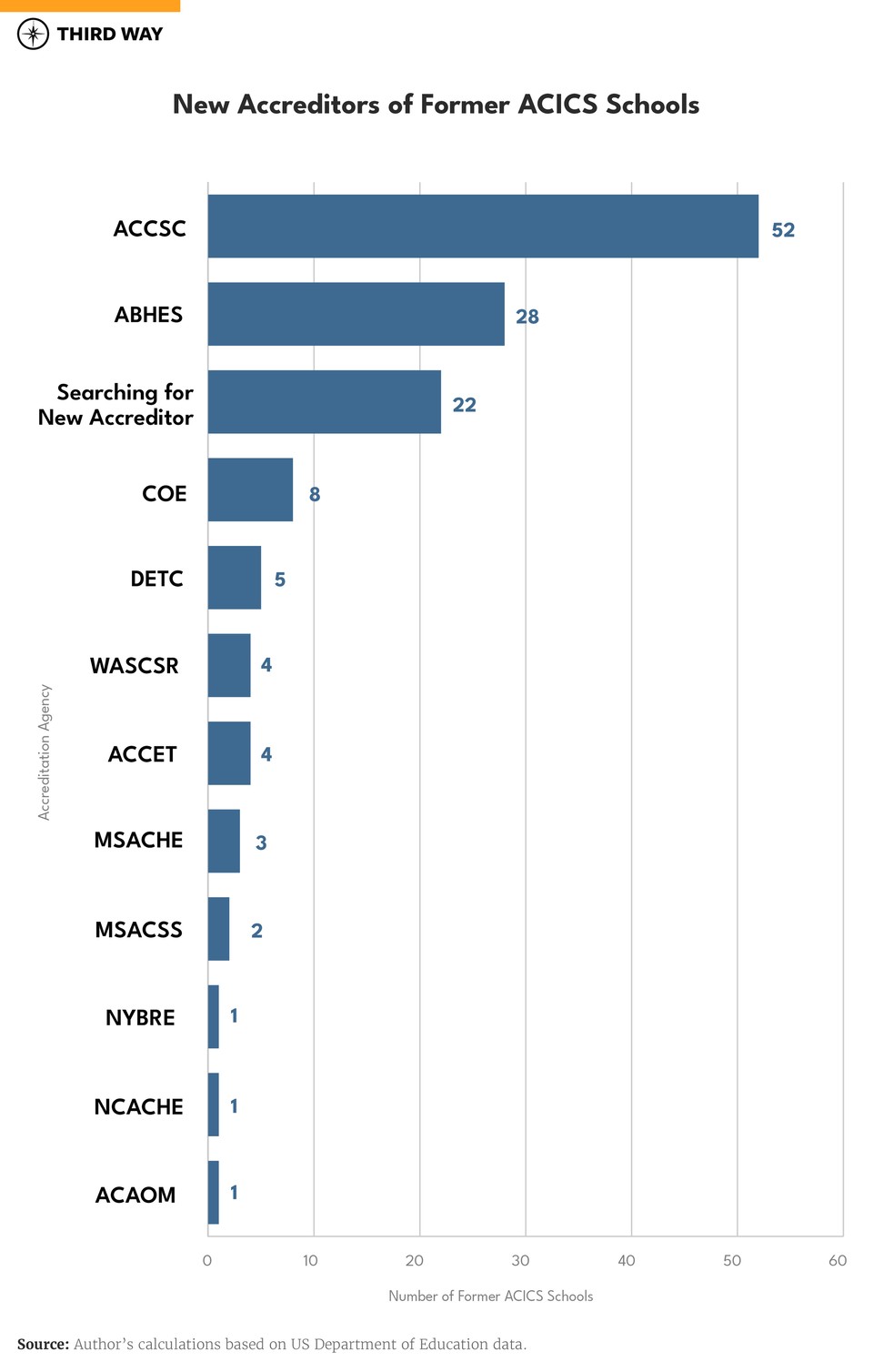

A plurality of former ACICS-accredited schools flocked to the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC). According to a Center for American Progress analysis, there were 269 schools accredited by ACICS at the time of their reinstatement in 2018.5 Based on our analysis of the Department’s most recent accreditation data, only 131 of those previous ACICS schools were still operating as of 2022. Fifty-two of those 131 schools relocated to ACCSC—another historically problematic accreditor—with the remaining 79 scattered amongst the alphabet soup of accrediting agencies. The next-largest receiver of ACICS schools was the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools (ABHES) with 28 schools, and 22 were still searching for a new accreditor as of July 2022.

Like ACICS, ACCSC primarily accredits for-profit institutions. In 2021, Third Way found that over a quarter of ACCSC schools showed no return on investment (ROI) using our price-to-earnings premium (PEP) metric. The price-to-earnings premium looks at the amount an average student pays out of pocket to cover tuition compared to how much they earn beyond a typical high school graduate within their state.6 This analysis also revealed that this portion of schools with no ROI for students received nearly $200 million in federal student aid. Making matters more frightening, 49 ACCSC schools were on heightened cash monitoring (HCM) status due to major financial compliance issues as of 2021.7 With the 52 ACICS additions, ACCSC now accredits over 350 schools and will receive around $3 billion in federal student aid each year.8

These findings make it evident that ACCSC already had a poor track record for quality with the schools it accredited prior to the 2022 ACICS shutdown. Will its 52 new institutions acquired from ACICS boost those outcomes? Unfortunately, that’s not likely.

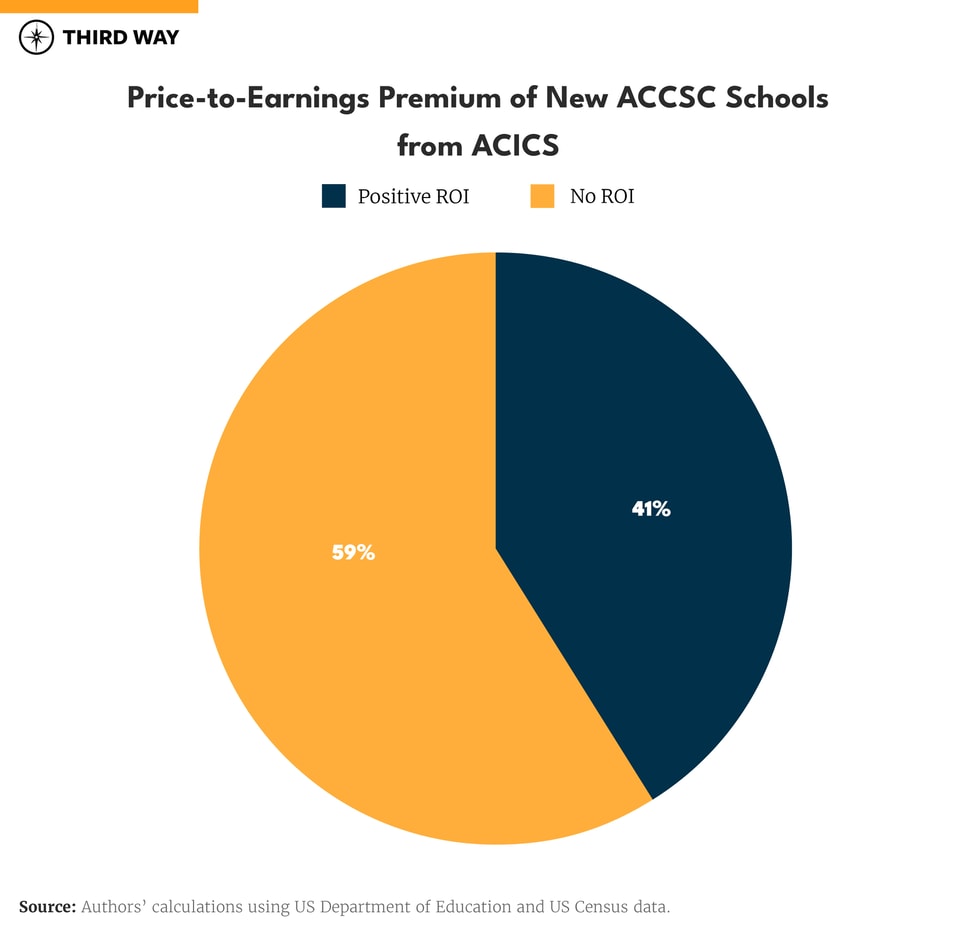

Our analysis of the schools that moved from ACICS to ACCSC, using available data, revealed that nearly 60% have no ROI for students. That means that over half of these schools are at high risk of saddling students with unaffordable debt and low incomes, making it impossible to pay down their loans. The median earnings of students completing degrees at these incoming colleges is $32,047, only slightly above the poverty line of $30,000 for a family of four.9 Despite these poor outcomes, this set of colleges will bring in $513 million in extra federal dollars under the umbrella of ACCSC. These moves will also bring in 11 additional schools that are on the heightened cash monitoring list to the accreditor’s portfolio.10 This combination of factors could be detrimental to the outcomes of promising students and society at large.

Conclusion

College accreditation has been receiving increased Administration attention to ensure that it’s meeting its mission, but some accreditors fail to do so. ACICS lost its federal recognition because it was asleep on the job, leading many poor-performing institutions to another accreditor with lax oversight. The Department needs to do more to hold accreditors and their institutions accountable to students and taxpayers—and keep an eye on the shifting trends in accreditor portfolios and performance in the post-ACICS landscape.

Methodology

To track the institutions that were accredited by ACICS, we used the data file from the 2018 Center for American Progress report “The 85 Colleges That Only ACICS Would Accredit,” which showed ACICS accrediting 269 schools at that time. Using this report and the latest Accreditor Data File from the Department of Education we found that 118 of the 269 schools subsequently either lost Title IV funding or are now closed, which left 151 schools to analyze. Of the 151 schools left, 131 could be verified in the latest Accreditor Data File and were the basis for this analysis. Given the plurality of former ACICS schools from that set are now accredited by ACCSC, this product focused specifically on ACCSC as an accreditor and therefore took those samples of schools to measure ROI by calculating a Price-to-Earnings Premium.

Using the latest accreditation file, we found 52 past ACICS schools have moved to ACCSC. To apply Third way’s price-to-earnings premium, institutions needed data that included net tuition price and post enrollment earnings. Of the 52 schools, 41 had available data to apply the PEP metric, and those without data were excluded from this portion of analysis. More detailed information on the PEP formula can be found in the report, “Price-to-Earnings Premium: A New Way of Measuring Return on Investment in Higher Ed.”

Additionally, to construct the PEP metric for this report, we pulled data from the US Department of Education’s latest Accreditation file and the US Census Department’s American Community Survey (ACS). For the US Census Department’s American Survey, we used the 2021 5-year estimates from ACS to calculate a median salary of high school earnings by state.