Memo Published February 7, 2020 · 8 minute read

Forget 270: Dems Might Need 340 Electoral Votes to Get Anything Done

David de la Fuente

In 2020, Democrats have their eyes set on making Donald Trump a one-term president. How do they do this? By winning 270 votes in the Electoral College.

But even with Donald Trump gone, the next Democratic president and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi could be kneecapped by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell if he keeps control of the upper chamber. And the path to flipping the Senate is even tougher than the presidential race, especially when you consider that no matter how great individual Senate candidates may be, the person who will matter the most to determine whether McConnell maintains power will be the Democrat at the top of the ticket. Because while voters used to split their allegiance on a single ballot, supporting one party for Senate and the other for president, over the last two decades that behavior has gone rapidly out of style. If recent history is any guide, it will be near impossible for Democratic Senate challengers to oust Republican incumbents unless the Democratic nominee for president is also winning their state concurrently (or coming incredibly close). So to set themselves up with a Senate majority, a Democratic presidential nominee will need not only to rebuild the “Blue Wall” of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, but also beat Trump (or keep margins razor thin) in places he won in 2016 like Arizona, Iowa, and North Carolina.

The Tightening Link between Presidential & Senate Results

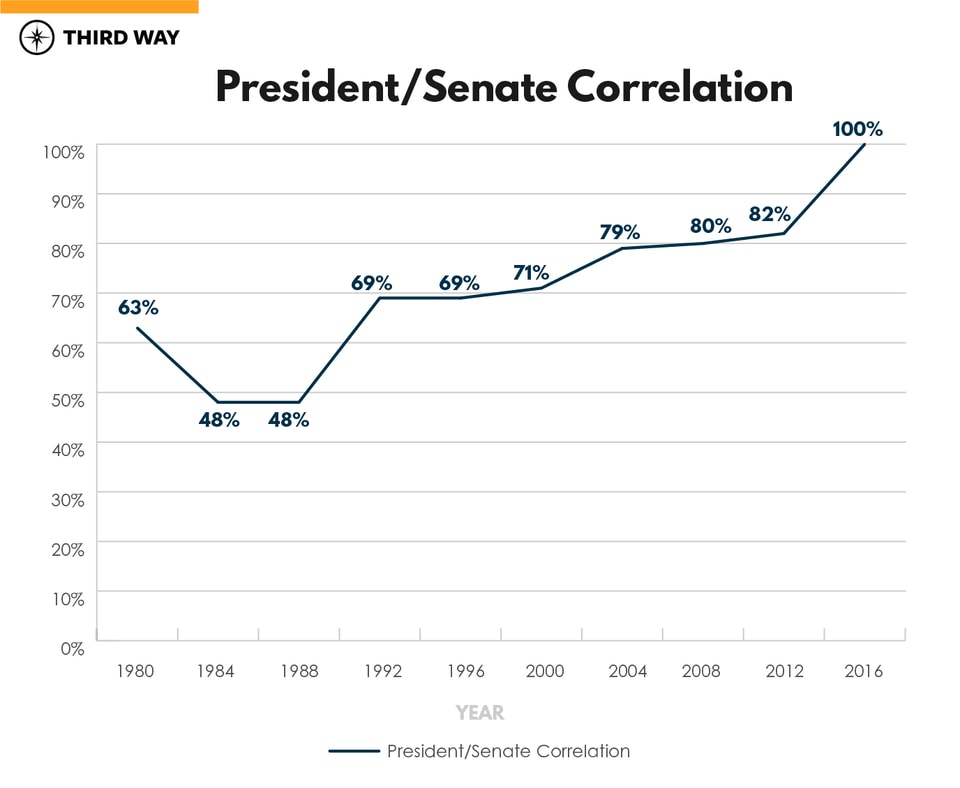

Over the last 20 years, the correlation between presidential and Senate results has increasingly tightened—leading up to 2016 when there appeared to be an ironclad locking of the two as intertwined elections.

Back in the Reagan-Bush days, the connection between presidential and Senate results was relatively weak. The highpoint was a 63% in 1980 when the Reagan revolution swept in 10 new Republican Senators on Reagan’s coattails. Yet Democratic Senators were able to outrun the GOP’s large Electoral College wins in both 1984 and 1988, when less than half of all races had the same party win both contests in a state.

This independence between presidential and Senate results really started to erode with Clinton’s election in 1992. The parties each ended that cycle with the same number of seats they had when they started, but the map shifted to align with the top of the ticket. That meant the GOP started to gain more Senate seats in the South, while Democrats started picking up seats on the Pacific Coast, Northeast, and Greater Lakes region. By 2000, 71% of Senate races went to the same party that won the presidency in that state, and that number jumped to 79% in 2004 with the GOP picking up several seats, all but ending the Southern Senate Blue Dogs in the South as Bush swept the region. The correlation continued to climb to 80% in 2008, and 82% in 2012.

The 2016 election brought a high-water mark that can’t be overtaken: 100%. This made it the first election since the advent of the direct election of United States senators in which every single senator who won belonged to the same political party that won their state at the presidential level.

This pattern leaves no doubt that ticket-splitting in presidential election years is declining at a rapid rate. While there are still a plethora of swing voters, as evidenced by large swings in results between cycles, many of them appear to joining with more partisan voters in sticking with one party at the federal level once they have made up their minds in a given year—making it nearly impossible to get split results in federal elections statewide.

Incumbent Senators in Presidential Cycles

This trend means that in modern politics, incumbent senators are practically impossible to defeat when their party is winning the presidential vote in their state. Since 2000, exactly 100 senators have run for reelection in a state that picked their party at the presidential level. Only two of those 100 lost, which means these types of senators have a win rate of 98%. And the two who won have caveats the size of Alaska.

In 2000, popular Governor Mel Carnahan (D) was running to unseat Senator John Ashcroft (R). Carnahan perished in an October plane crash one month before the election. He went on to become the only person in American history to win a Senate election posthumously after the new Governor pledged to appoint Carnahan’s grieving widow. In 2008, Anchorage Mayor Mark Begich (D) unseated long-term Senator Ted Stevens (R). One week before the election, Stevens was found guilty in federal court on seven counts of making false statements. These two cases are highly abnormal, and not surprisingly, both Begich and Jean Carnahan—Mel’s widow—lost in their subsequent midterm election.

On the flip side, senators running for another term in states that vote for the presidential nominee of the other party only have a 64% win rate across the past five cycles, and that number has decreased over time. From 2000 to 2008, the win rate was 66%, but in just the past two cycles it has dropped to 57%. And of course, it fell to zero in 2016, as both senators running for reelection in states their party lost at the presidential level were ousted.

The Implications for 2020

Democrats’ path to the Senate majority relies on defeating Republican incumbents, as no major retirements have opened up opportunities to flip seats. Given the data outlined above, this will be a difficult feat. There were nine states in which national Democrats invested heavily to unseat a Republican incumbent in 2016, and Hillary Clinton got 46% of the vote in those states. On average, these Democratic challengers also earned exactly 46%.

Democrats currently have 47 seats in the Senate. They can’t take any state for granted, but considering that 10 of their 12 senators up in 2020 come from states Hillary Clinton won in 2016, and they will almost certainly have to win Senator Gary Peters’ (D) home state of Michigan to win the presidency, they have a good chance to hold 11 of these Senate seats. That would give them 46, which means they need to win four more to get to the majority if they win the White House.

The 12th Democratic seat that’s up is that of Senator Doug Jones (D) of Alabama. Jones remains popular, but to win he will have to seriously outperform the top of the ticket in a state that will almost certainly vote for Donald Trump for president by double digits. Depending on the results in Alabama, Democrats will need to flip three or four Senate seats currently held by Republicans.

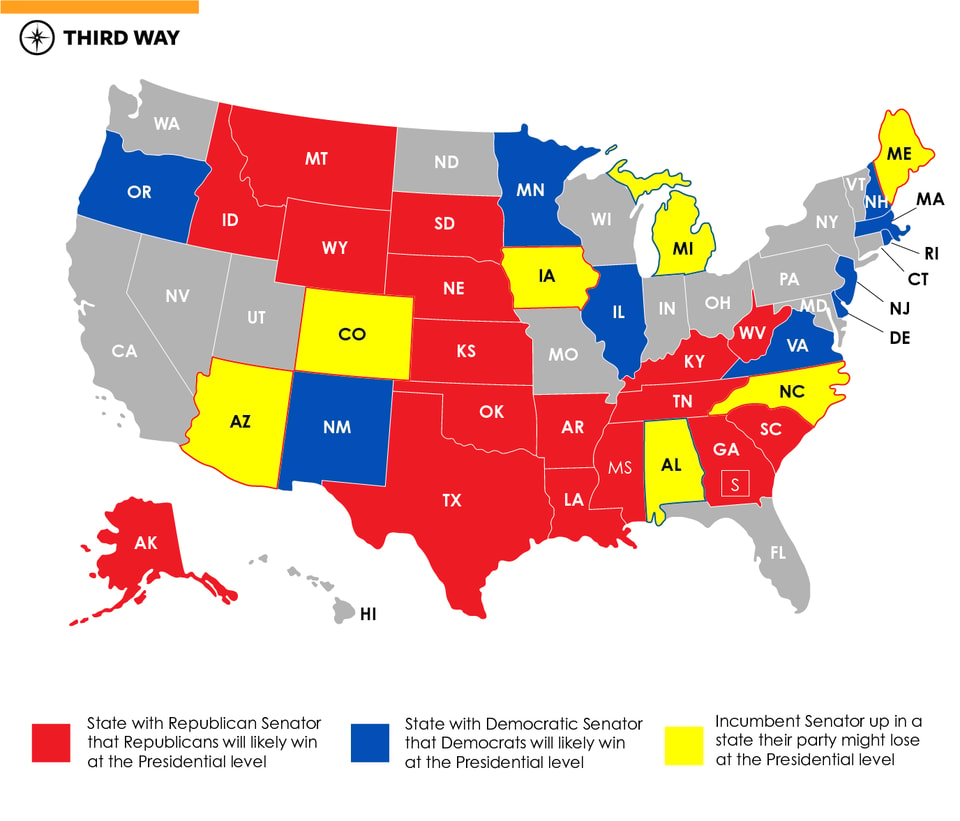

The five best targets are in states that appear most likely to vote Democratic at the presidential level in 2020—or at least be close. Republican Senators Cory Gardner (CO) and Susan Collins (ME) are trying to win reelection in states that Hillary Clinton won in 2016. Democrats will probably need to win these two states at the presidential level to win the presidency, so they’re obviously appealing targets for Senate flips given the confluence of results we describe above.

Two other Republican incumbents are running in states that Barack Obama won in at least one of his presidential victories: Senators Joni Ernst (IA) and Thom Tillis (NC). The fifth target is a Romney-Trump state, but it’s one that shifted toward Democrats in 2016 and 2018. Hillary Clinton lost Arizona by less than half the margin Obama did in 2012, and the state elected a Democratic senator in 2018. The incumbent is Senator Martha McSally (R), who lost the 2018 Senate race but was subsequently appointed to this seat after the death of John McCain.

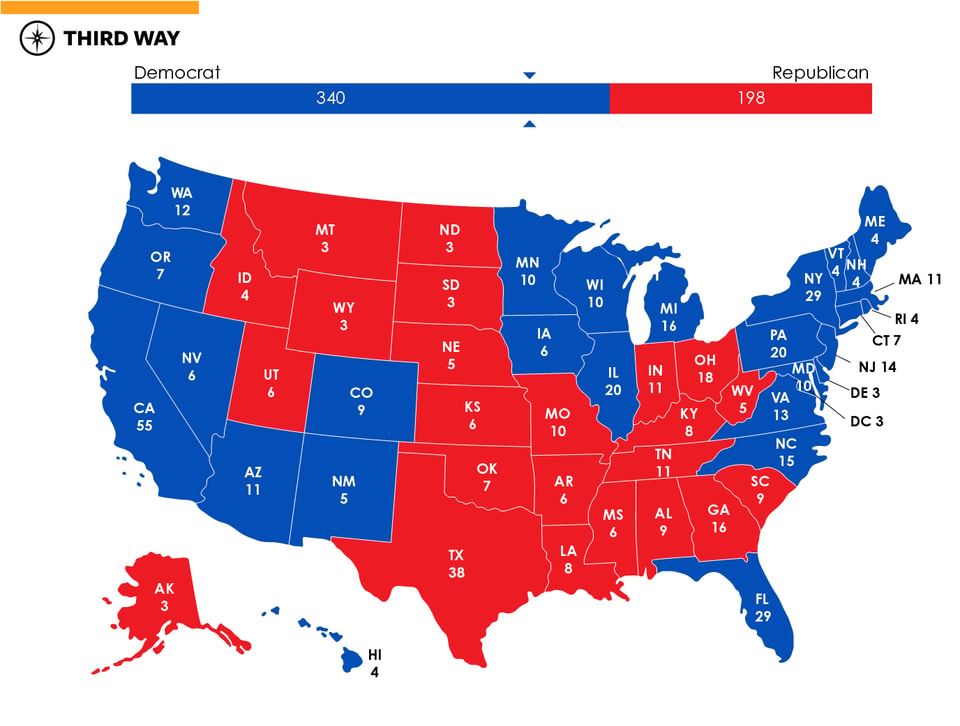

These are the five states that will determine whether a Democratic president can get anything done in 2021. If Democrats lose Jones due to the Presidential/Senate correlation phenomenon, they will need to knock off at least four of these five Republican incumbents. And if, as recent history predicts, the Senate results track closely with the top of the ticket, winning Senate seats in these five states would also require them to win the Electoral College with a total upwards of 340 votes. (As a note, we are guessing that any Democrat who wins Arizona, Iowa, and North Carolina, probably also wins Florida along the way; though, this is not necessary to win the Senate as Florida doesn’t host a 2020 Senate contest.)

There is cause for hope though. In both 2000 and 2008, Democratic Senate candidates defeated four Republican incumbents in states that went Democratic at the presidential level. If Democrats can win in a bunch more states at the presidential level, the hope of a Senate takeover becomes bright.

Conclusion

In 2020, Democrats can get to the White House with just 270 Electoral votes by rebuilding the “Blue Wall” in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. But to win the Senate, they need to beat a whole bunch of Republican incumbents as well—many of whom hold seats in an even redder territory. Recent history has shown this will be next to impossible without the top of the ticket being able to compete and win (or keep the margin incredibly close) in places like Arizona, Iowa, and North Carolina.

Beating Trump by a large margin is Democrats’ only hope of gaining a federal trifecta government to pass their agenda. If the Electoral College map doesn’t look like this, Democrats could have Mitch McConnell blocking every move of the new Democratic president.