Memo Published October 16, 2019 · 18 minute read

Five Big Updates the College Affordability Act Makes to HEA

Lanae Erickson, Tamara Hiler, Michael Itzkowitz, Michelle Dimino, & Shelbe Klebs

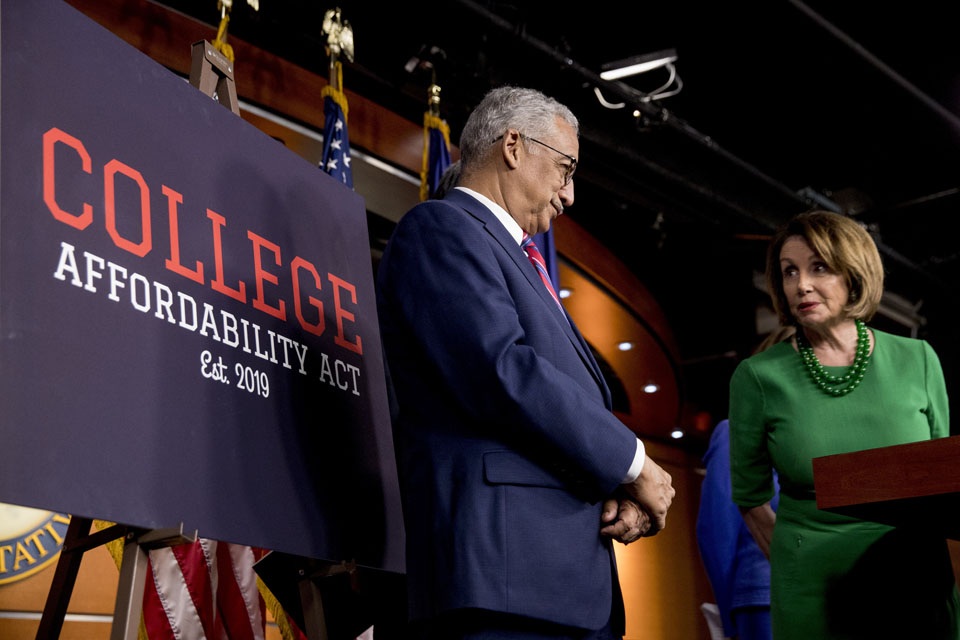

Last month, the House Education & Labor Committee under Chairman Bobby Scott (D-VA) passed out of committee the College Affordability Act (CAA), a long-awaited Democratic reboot of the decade-old version of the Higher Education Act (HEA), which is no longer delivering on its promise to provide students and taxpayers a return on their educational investment. As the House moves CAA through the legislative process, this memo highlights five major policy updates in the legislation and explains how those policies diverge from current HEA law.

Transparency

Under HEA: Available information on student outcomes is limited by a current federal ban on student-level data that was instituted through amendments to HEA in 2008. Even though the Department of Education (Department) has made efforts in recent years to expand its reporting on student outcomes by updating the Outcomes Measures survey in its Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) system to include part-time and non-first-time students, the federal graduation rate written in statute today only measures students who attend college for the first-time on a full-time basis. This definition only encompasses a small proportion of today’s college students (approximately 40%), and it overlooks the growing number of students attending school on a part-time basis and those who transfer from one institution to another, especially those who move across state lines. Further, post-enrollment employment and earnings outcomes are limited to students who have received a federal grant or loan, leaving out nearly a third of all students. Gaps in the current data system can make it difficult to get a full picture of institutional outcomes and limit the information available to students making important choices about where to attend college.

Under CAA: The CAA addresses these shortcomings by fully integrating language from the previously-introduced bipartisan College Transparency Act that removes the federal ban on student-level data and creates a secure postsecondary data system, making accessible more complete information on graduation and employment outcomes while safeguarding student privacy. The CAA provides for the collection of data points on students throughout the course of their education and across all types of institutions, including more nuanced insight on the growing population of transfer students. The bill requires that those data points be thoroughly disaggregated to provide a fuller picture of how well institutions and specific programs of study within institutions are serving all students. These enhancements to the federal data system will both help prospective students make better decisions on whether an institution or college program provides a good return on investment and promote institutional improvement. Additionally, the bill would improve transparency around how institutions serve all students by requiring the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to report on the racial and socioeconomic gaps in enrollment, debt repayment, and graduation rates for public institutions, as well as mandate that colleges explain to students and prospective students any tuition increase greater than 5% and identify which costs were related to non-instructional spending.

The Upshot: When choosing an institution of higher education, students and families deserve the most complete information on how well a school serves its students. Yet right now, federal data only reflects a sliver of today’s students and information about how well institutions serve all students can be hard to find. The CAA provides enhanced information on college outcomes, empowering prospective students to make better decisions on where to attend and incentivizing institutions to focus on strategic improvements. It also provides better data for policymakers, which is critical for deciding how taxpayer dollars can best be targeted to ensure a strong return on investment.

Accountability

Under HEA: The only accountability metric codified in HEA today is the outcomes-based guardrail known as the Cohort Default Rate (CDR). Originally written into law in the 1980s, CDR was intended to curb alarmingly high student loan default rates by creating a “test” that would allow Congress to limit an institution’s ability to receive federal financial aid if a certain percentage of its students defaulted on their loans within a certain number of years after entering repayment.1 The most recent update to the CDR came through the last reauthorization of HEA in 2008, and includes two tests that can make an institution ineligible to receive federal student grants or loans: 1) If an institution has a CDR of 30% or higher for three consecutive years; or 2) If an institution has a CDR of over 40% in any one year.2 Institutions can only appeal their CDR if they serve a high percentage of economically disadvantaged students or if a small percentage of the student body takes out student loans. Under current law, an institution’s CDR does not include students who are in deferment or forbearance—a loophole that makes CDR easy for institutions to manipulate by encouraging former students to enter into forbearance or deferment as a way to subsequently bump them outside the measurement for CDR.3 This in turn has rendered CDR essentially toothless—capturing fewer than 1% of all institutions each year.4

Under CAA: Recognizing that the current CDR is insufficient, the CAA makes two substantive changes to how the federal government would identify and hold institutions accountable for setting up students to repay their federal loans. The first is that it shifts the current CDR to a new “Adjusted Cohort Default Rate” (ACDR) that multiplies an institution’s CDR by the percentage of students at that school who borrow federal loans. This new ACDR also adds in three tests (instead of two) to measure student outcomes as far out as eight years after entering repayment (instead of three) to determine whether an institution is ineligible to receive federal student grants or loans. This includes sanctioning schools that have an adjusted CDR greater than 20% for three years, greater than 15% for 6 years, and greater than 10% for 8 years. Lastly, the ACDR closes the “forbearance loophole” that allows institutions to game the system, making it harder for any one institution to hide the number of students in serious financial distress.

Secondly, CAA adds in an entirely new accountability framework that takes into account students’ on-time repayment rates and uses institutional spending to determine how well federal dollars are actually being used to support students. Specifically, this bill introduces a new “on-time repayment rate” metric, which looks at the percentage of borrowers at an institution who have paid 90% of their monthly payments within 30 days of the due date, including those whose payment is zero because of income-driven repayment (IDR), those who have certain deferments outside of economic hardship or unemployment, and those who are in forbearance for less than 18 months. The Secretary of Education (Secretary) will set a threshold or thresholds (the bill allows setting more than one) for how many borrowers need to be in on-time repayment, and those that fall below will then be passed through an instructional spending screen that looks at how much money the institution spends on teaching. Schools that spend less than one-third of their net tuition per full time student on instruction are no longer eligible to receive Title IV financial aid funds, while schools that spend more are required to make a repayment management plan that the Secretary must approve.

The Upshot: It’s no secret that the current CDR is ineffective at the job it was meant to perform. The CAA will create a much more serious federal bottom line on defaults that will enable the Department to catch more schools that are consistently failing their students than the paltry dozen sanctioned by today’s CDR formula. It’s also a big step forward that the CAA will supplement and not supplant CDR with a new on-time repayment rate. Multiple metrics of success are critical in any accountability framework, which can provide an important flag to students and taxpayers about the schools that may be sending a high percentage of their borrowers into distress before getting into default. Lastly, it’s very encouraging to see an accountability framework that also looks at instructional spending, which can help to differentiate between institutions that cannot invest more in their students due to a lack of resources (places where we should build capacity) and those that can but choose not to despite dismal student outcomes (places where we should cut off federal funds).

However it should be noted that while the inclusion of an “on-time repayment rate” metric in addition to the cohort default rate is a huge step in the right direction for accurately measuring whether an institution is providing value to its students, there is significant room to strengthen the repayment rate language included in the bill to ensure it more comprehensively identifies whether students are able to pay down the debt they incurred to finance their postsecondary education. Specifically, the bill allows students making zero dollar payments under an income-driven repayment plan to count positively toward on-time repayment, creating a situation where it is difficult to accurately measure how many borrowers a school produces with unmanageable debt. There is also room to strengthen the bill around the threshold for what proportion of borrowers need to be in on-time repayment at an institution. The language currently leaves the threshold up to the Secretary to decide, and if future administrations follow the lead of this current one, that could result in extremely low expectations and could render this metric toothless in its ability to truly account for a school or program’s ability to set its students up for financial success.

Accreditation

Under the Current HEA: Under current federal law, accrediting agencies are meant to serve a pivotal role in ensuring that institutions provide a basic level of educational quality for students and continuously improve their efforts to do so. To become accredited, an institution must go through an evaluation process, which includes a self-study and an on-site evaluation, at which faculty and administrators from fellow member institutions assess whether the institution meets those standards. This peer review process assumes that some level of educational quality is being maintained, however, the current accreditation process is not outcomes-focused, making it difficult to accurately evaluate how well institutions are serving students. Each individual accreditor determines what standards and definitions to use in accreditation and the pre-accreditation process, but these standards do not have to be consistently applied to every institution. And while HEA states that these standards must “address quality in student achievement that relate to the institution’s mission and can include course completion, state licensing exams, and job placement rates,” a lack of consistency and oversight across accrediting agencies makes it impossible to accurately compare outcomes across institutions. It also helps explain why a handful of schools remained “accredited” until the day they closed.

Under CAA: The CAA strengthens the accreditation process by shifting it to focus more on student outcomes. The bill requires a working group to create a glossary of common definitions for student outcomes, which will allow us to have a more apples-to-apples appraisal of how well institutions are doing both within and across accreditors’ portfolios. Common definitions will be set for performance measures in three buckets: completion, workforce participation, and measures that assess progress of an institution toward meeting the standards for completion. Accreditors must select one measure from each bucket (totaling three required standards) to use in the individual evaluation of institutions. They also may use measures not listed in the glossary to assess student outcomes, including using different measures for different institutions if they so choose. Accreditors will also be required to set performance benchmarks that each educational program will have to meet for each measure used. Finally, the CAA requires additional public reporting of outcomes by institutions and accreditors and reduces the conflict of interest among governing bodies of accrediting agencies while increasing financial responsibility standards. These changes will make institutional evaluation more robust and provide a clearer picture of how institutions perform.

The Upshot: Even though accreditation is built on the ideas of self-assessment, peer review, and continuous improvement, our current system prevents meaningful comparisons of outcomes across institutions, which makes it difficult for students and taxpayers to accurately assess educational quality. As a result, accreditation currently focuses on factors beyond student achievement, often providing more uncertainty, rather than assurance, that students will leave with a high-quality credential that prepares them to succeed in the workforce. Refocusing accreditation on what matters most—student outcomes—will target accreditors’ limited resources on completion and workforce outcomes. Specifically, requiring a glossary of common definitions in CAA will benefit both accreditors and institutions looking to speak a more shared language around how to benchmark performance and more effectively evaluate student achievement. And while these initial changes represent an important first step towards strengthening the quality assurances that accreditors are supposed to provide, there is still significant room to push the accreditation process to focus on outcomes even further by requiring additional quality measures to be used in the evaluation process and holding accreditors responsible for the outcomes of students at the schools they accredit.

Short-Term Pell

Under HEA: The Pell Grant program is the federal government’s most significant investment in student financial aid for low- and moderate-income students. Under the current HEA, Pell Grants can only be used for eligible educational programs that provide at least 600 clock hours of instruction over a minimum of 15 weeks—requirements that were established in the 1992 reauthorization of the law in response to a well-documented cycle of fraud and abuse by predatory short-term programs.5

Under CAA: The CAA expands Pell Grant eligibility to shorter programs at non-profit institutions that provide at least 150 clock hours of instruction over a minimum of 8 weeks, allowing students to use their Pell grant funding to attend high-quality, short-term workforce training programs. To affirm that programs receiving these funds are providing a quality education, the CAA establishes a minimum earnings threshold for eligibility that corresponds with the average or median earnings of a high school graduate. Programs will be reevaluated once every three years based on their graduates’ earnings, and a variety of additional data points on student outcomes will be collected to promote transparency and accountability as we learn more about the value short-term programs can provide. The new bill also includes provisions to ensure that credits received from short-term programs will be eligible for transfer to related degree programs and that non-credit coursework can be converted to credit if a student later decides to continue their education—measures that incentivize schools to offer quality credentials and strengthen the connection between short-term programs and traditional associate and bachelor’s degrees.

The Upshot: Any expansion of Pell Grant eligibility to new programs must be accompanied by strong guardrails to protect the investment of students and taxpayers, as we’ve seen in the past that a lack of guardrails can open up new avenues for predatory schools to target vulnerable students and leave them worse off than when they enrolled. By setting a minimum earnings threshold, creating outcomes-based standards for program review, and promoting clear credit articulation, the CAA embeds quality control mechanisms to ensure that Pell Grant dollars only flow to high-quality programs that equip students with a valuable credential and increase their earning potential.

Consumer Protections

Under HEA: The current HEA language offers few robust consumer protections to limit risk for students and taxpayers investing in postsecondary education, and for those that do exist, loopholes in the law have created avenues for bad actors to take advantage of federal funding—and of students seeking opportunity through education. For example, as the law stands now, for-profit colleges can only receive up to 90% of their revenue from federal financial aid grants and student loans issued by the Department under Title IV. This revenue ratio—known as the 90-10 rule—is designed to ensure that for-profit institutions bring in at least 10% of their revenue from non-federal sources, an important indicator that their programs are providing value to students. But the law does not count federal funds reserved for veterans through the GI Bill and Defense Department Tuition Assistance program toward for-profit institutions’ 90% federal funding cap because they are not administered through HEA—resulting in predatory for-profit colleges often aggressively marketing themselves to service members and veterans as a way to stay below the cutoff for eligibility for federal funds.

Additionally, the Obama Administration attempted to create another consumer protection in 2014 through its Gainful Employment rule (GE), which offered a formal definition for a previously undefined phrase in HEA that stipulates that programs receiving funding under Title IV must “prepare students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation.” The GE rule aimed to protect students from predatory programs and preserve the integrity of federal financial aid funds by establishing parameters to identify and hold accountable career education programs that consistently left their graduates unable to repay their educational debt—and it worked, catching about 800 poor-quality programs.6 But because the GE rule was regulatory and not statutory, the current Department of Education was able to rescind the GE rule, effective July 2020. Similarly, the current Department has also worked to weaken borrower defense to repayment regulations first installed in the Obama Administration, making it more difficult for students who were defrauded by colleges to have their federal loans discharged.

Under CAA: The CAA includes several measures to strengthen consumer protections for veterans and students. The new bill closes the 90-10 loophole by disallowing for-profit colleges from counting funding from non-Title IV federal programs, like the GI Bill, toward their non-federal funding requirement. It also updates the 90-10 rule to a new ratio of 85-15, so that educational programs cannot receive more than 85% of their revenue from federal financial aid. The strengthened regulations will protect student and taxpayer dollars from low-quality institutions, helping to ensure that service members and veterans see a real return on investment from their military education benefits. As a further protection against predatory institutions wasting student and taxpayer dollars, the CAA also introduces a screen of institutions’ spending that will identify schools that focus their federal resources heavily on marketing, recruitment, lobbying, advertising, or other non-instructional expenditures. Under the screen, if an institution spends less than one-third of its revenues from tuition and fees on instruction in any of the three most recent fiscal years, it will be subject to a one-year ban on marketing-related spending of federal funds. And if an institution fails the test in two consecutive fiscal years, it risks losing access to Title IV funds for at least two years.

The CAA also formally codifies a definition of “gainful employment” into the HEA for the first time, establishing a negotiated rulemaking process through which the Department will establish debt-to-earnings requirements for the same types of certificate and degree-granting programs originally covered by the now-defunct GE rule. This represents a significant step forward in ensuring that poor-performing institutions will be held accountable for the earnings outcomes of their students. Additionally, to protect defrauded student loan borrowers, the CAA requires the Department to establish a process for borrower defense to repayment under which to discharge federal loans of students who were the victim of fraud by their institutions. All types of federal student loans are eligible to be discharged under the bill’s parameters, and students whose loans are discharged will also be eligible for restored eligibility for Pell Grant funding to continue their education.

The Upshot: The higher education system has historically lacked meaningful protections to limit risk for students and taxpayers investing in postsecondary education. The CAA takes critical steps toward embedding consumer protections into statute by helping to close the 90-10 loophole that allows for-profit colleges to defraud military veterans, incentivizing institutions to focus their financial resources on student instruction, codifying the definition of gainful employment into federal law, and ensuring that defrauded student borrowers can seek relief from their debts.

Conclusion

Higher education is one of the biggest investments someone can make in their lifetime, and a decade-old version of the Higher Education Act is no longer delivering on its promise to provide students a return on their investment. Today, we know that less than half of students who start college make it across the finish line, and those who start and don’t complete are three times as likely to default on their loans, making debt and no degree a reality for far too many Americans. The College Affordability Act makes large strides to improve outdated (and nonexistent) transparency, accountability, and consumer protection measures in the current authorization of HEA. More Americans are looking to reap the economic benefits of postsecondary education than ever before, which is why as Congress continues to move through the HEA reauthorization process, now is the perfect time for policymakers to implement the guardrails outlined in this bill in order to truly ensure our higher education system delivers for students and taxpayers.