Memo Published November 2, 2022 · 25 minute read

Electric Vehicles: Policies to Help America Lead

Alexander Laska & Ellen Hughes-Cromwick

Takeaways

- The US has broad-based potential to build a competitive advantage in electric vehicle manufacturing and in other value chain segments in the EV industry. Doing so would enable US automakers and suppliers to create hundreds of thousands of jobs and create tens of trillions of dollars in market value through mid-century.

- Recent legislation, including the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act, have created important programs such as tax credits and manufacturing grants that will accelerate the EV transition and help to secure US leadership.

- But to build a lasting competitive edge, more policy tools need to be deployed. This could include boosting federal funding for RD&D of improved EV batteries, automated vehicle technologies, and advanced manufacturing; accelerating federal procurement of EVs and the buildout of EV charging infrastructure; retraining the auto workforce for EV assembly and battery production while preserving job quality; and streamlining federal permitting processes to make it easier to start new extraction operations while maintaining rigorous environmental standards.

Why the US Should Compete in the EV Market

Earlier this year, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) released a groundbreaking report commissioned by Third Way and Breakthrough Energy finding that strategic investments in six key clean energy technologies could yield massive and lasting benefits for the US economy. Of the six technologies BCG analyzed, electric vehicles (EVs) represented the biggest economic opportunity by far.

And for good reason: The global transition to EVs is well underway, with EV sales worldwide doubling between 2020 and 2021. The transition comes with tremendous opportunity for US automakers and suppliers to capture tens of trillions of dollars in market value and create hundreds of thousands of jobs between now and 2050—by far the largest market potential of any technology BCG analyzed—while providing consumers with cleaner, more affordable cars.

But it also comes with risk: China’s dominance over critical mineral extraction and processing and battery production has left US companies susceptible to supply chain disruptions and threatens their standing as leaders in this industry.

At the same time, the dawn of autonomous and connected vehicle technologies is closely tied to the EV transition as customers expect increasingly connected features in their vehicles. This creates additional opportunity for US software developers and aftersales service providers—two areas where the US can maintain and grow its existing competitive advantage.

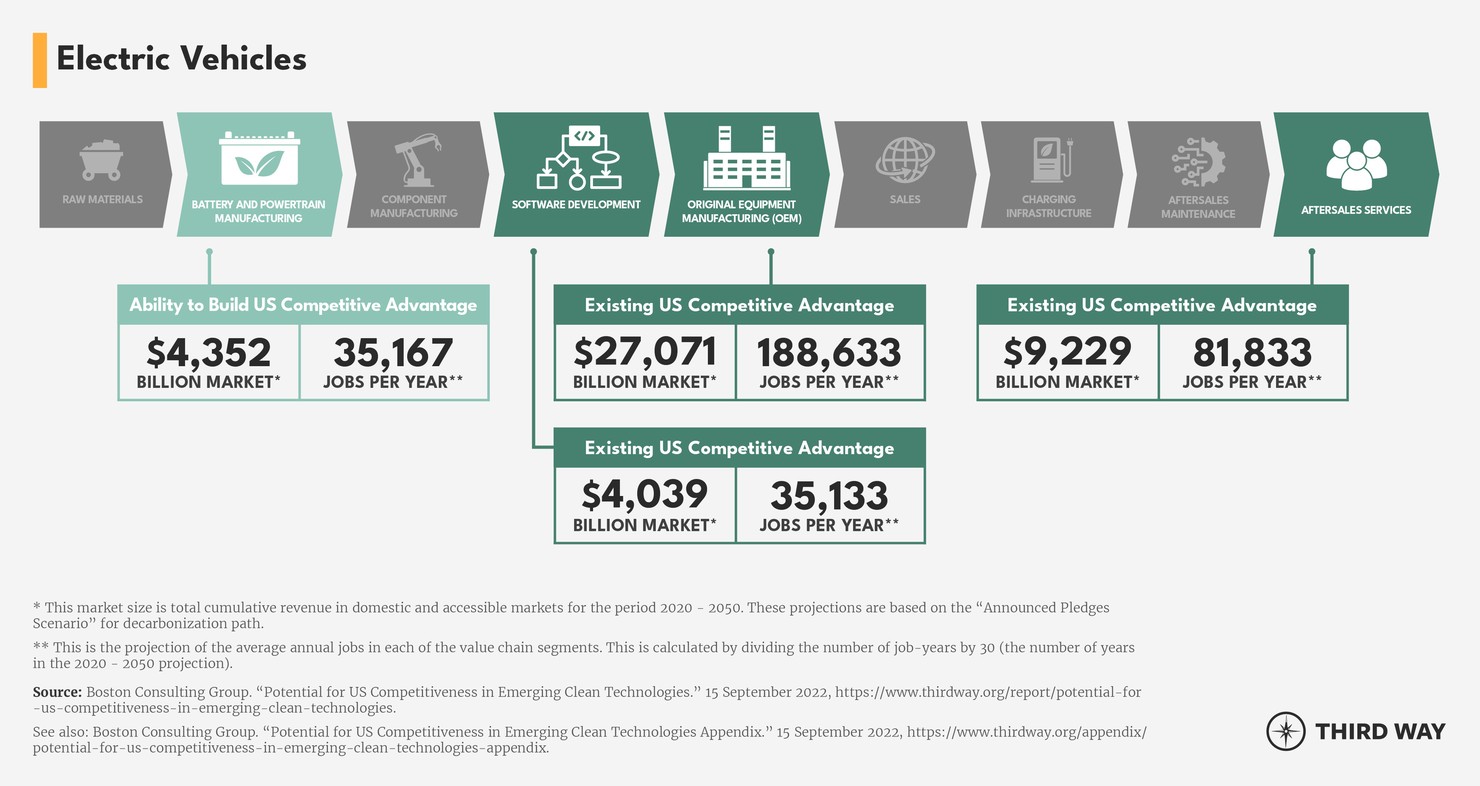

BCG’s analysis of the EV value chain identified the four most compelling segments based on market size and the potential for US competitiveness: battery and powertrain manufacturing, original equipment manufacturing (OEM), software development and aftersales services. The US already holds a competitive advantage in some of these segments and with the right policies can grow that advantage. BCG found a large serviceable addressable market (SAM)—the total global market excluding countries where US exports are unlikely due to political or economic barriers1—across these key segments, amounting to as much as $1.06 trillion annually by 2050 thanks to the massive global demand for automobiles and significant public and private investment in vehicle electrification.

BCG also found significant job potential in these four value chain segments, with the US able to compete for as many as 10.2 million jobs between 2020 and 2050. This will include a range of different jobs, from jobs in battery production and EV assembly plants that don’t require higher levels of education, to high-income jobs in software development that require college degrees.

In addition to these four key value chain segments, we also include raw materials in this report. While BCG did not identify raw materials as a value chain segment where the US could have a competitive advantage, we opted to include it given its importance to the entire supply chain and the risks associated with China’s dominance over this segment.

Policy Recommendations

Technology wide

US automakers and suppliers are already retooling for EV production, and we are seeing this movement accelerate thanks to the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. However, there’s more we need to do to catch up to the pace set by competitors in China and Europe. Additional federal support can be short-term, aiding the initial buildout of the domestic supply chains needed to secure a durable competitive advantage that will endure long after these programs have sunset.

Big Wins for EV Manufacturing in the Inflation Reduction Act

- $2 billion in Domestic Manufacturing Conversion Grants to help automakers and suppliers retool their factories to make EVs and EV components;

- A new Advanced Manufacturing Credit (45X) to incentivize production of critical materials, batteries, and other clean energy technologies;

- A 10-year EV purchasing tax credit, which has new requirements around sourcing of critical minerals and battery components to push EV and battery makers to bring their operations to the US and secure the EV supply chain; and

- A new credit for purchasing a previously owned EV, which will further incentivize automakers to produce EVs by increasing the amount a leased EV is worth when the lease expires.

Ensure the new consumer incentive is workable: While battery costs are coming down, EVs remain expensive compared to their internal combustion engine (ICE)-powered equivalents. The EV tax credit is critical to achieving price parity with ICE vehicles. Not only will it reduce the upfront price of an EV in the near-term, but in driving demand for EVs it will also help automakers fill their plants to capacity and achieve the economies of scale needed to bring down costs. Boosted domestic demand for EVs will catalyze private sector investment in all segments of the value chain as the industry scales up to meet this demand, which will help our automakers compete with cheaper, foreign EVs.

The Inflation Reduction Act makes several important changes to the EV tax credit.2 The credit now requires final assembly to occur in North America and will soon come with increasingly stringent requirements related to the sourcing of critical minerals and battery components, including prohibiting any raw materials or battery components sourced from China or other “foreign entities of concern.” These new requirements will limit the number of EVs that are eligible for the credit and thus have a dampening effect on demand for EVs in the short term, but they will ultimately boost domestic manufacturing and help build out secure, reliable supply chains for EVs.3

In implementing the new credit, the IRS should ensure these requirements—particularly those around critical mineral sourcing—are workable for OEMs while maintaining Congress’s intent. For example, half of the new credit will now require an increasing percentage of the critical minerals to be extracted or processed in the US or in a country with which the US has a free trade agreement (FTA). The IRS should interpret this clause to mean that critical materials extracted in a FTA country but processed in a non-FTA country will count towards this requirement for the next few years, before an additional change comes into effect in 2025 that prohibits any critical materials extracted, processed, or recycled in China or other “foreign entities of concern.” China owns roughly 75% of the world’s critical material processing, so how the IRS interprets this requirement will have a big impact on which EVs qualify for the credit over the next few years.4

Boost Federal RD&D Funding: Research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) of new EV battery technologies is critical to improving battery performance, increasing range, and decreasing charging time, all of which will make American-made EVs more attractive to customers. Yet as the BCG study points out, the US lags far behind East Asia in IP generation in multiple areas, with one exception being aftersales services software. The US must ramp up funding for RD&D on a wide variety of topics—such as battery performance, critical mineral extraction and processing, battery recycling, and advanced manufacturing—so we can develop and own the next generation of capabilities in all parts of the value chain.

This means expanding funding for EV-related RD&D at the Department of Energy including the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), the Advanced Manufacturing Office (AMO), ARPA-E, the Office of Science, and National Lab-driven efforts such as Li-Bridge which will help build out supply chains for lithium-ion batteries. Boosted funding for these programs will help maintain and grow US IP and technical leadership across value chain segments, leading to a more durable competitive advantage.

Battery and powertrain manufacturing

As our domestic auto industry shifts production towards EVs, it will become more reliant on having steady access to batteries. Battery production is currently concentrated in East Asia, with China alone owning 75% of the world’s production of cathode and anode material (key components of battery cells) and 75% of the world’s battery cell production.5 This lack of domestic production capacity is putting the US at a disadvantage, and so ensuring reliable access to batteries needs to be a priority.

BCG assessed that this value chain segment has among the highest cumulative SAM of any segment they examined across technologies, valued at $4.35 trillion through 2050. It also ranked among the highest segments for potential job creation: the US could create over one million jobs during the 2020-2050 period depending on how much of the market the US can win. Importantly, BCG assessed that 60% of these jobs could be created in target communities (disadvantaged communities and those impacted by the energy transition).

Continue scaling up manufacturing assistance: BCG assessed that existing infrastructure is a key dimension of this value chain segment, and the US does not currently have the battery manufacturing capacity needed to compete on the global market, particularly in cell component manufacturing. This is starting to change thanks to policies Congress has passed to help build a competitive domestic industry for battery manufacturing, and this support will be critical to help US companies build or retool facilities for the powertrains of the future and achieve the scale needed to compete with cheaper foreign alternatives.

Congress has taken several steps to incentivize domestic manufacturing of EV batteries. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes over $3 billion for domestic battery production and recycling. Congress also provided $52 billion to support domestic semiconductor production as part of the CHIPS and Science Act. Most recently, Congress funded several programs through the IRA including the Advanced Manufacturing Credit (45X), which provides tax credits for manufacturing battery cells, modules, and critical minerals in the US; $2 billion in Domestic Manufacturing Conversion Grants for domestic manufacturing of electric and other clean vehicles; and $10 billion in Manufacturing Tax Credits, which will help fund a variety of clean energy manufacturing including zero-emission vehicles and their components. All of these programs will help create economic competitiveness until scale is achieved—and we’re already starting to see the domestic battery industry accelerate thanks to these policies.

One key implementation question is whether joint ventures (JVs) will be eligible for the 45X credit. The JV business model is gaining prominence as OEMs want to have control over as much of the supply chain for these new vehicles as they can. General Motors (GM), for example, has created a JV with LG Energy called Ultium Cells, which will manufacture EV batteries in the US. The IRS should ensure a JV selling batteries to one of the parties of the venture (for example, Ultium producing batteries for GM) can claim the 45X tax credit.

Ultium Cells LLC

GM and Korean company LG Energy Solution established Ultium Cells LLC, a joint venture that will mass-produce Ultium battery cells. Ultium Cells will provide battery cell capacity to support GM’s North American EV assembly and has announced over $7 billion in investments to build battery cell manufacturing facilities in Ohio, Tennessee, and Michigan, creating thousands of jobs in those states. The Department of Energy has announced a conditional commitment to Ultium Cells for a $2.5 billion loan to help finance the construction of these facilities.6

This partnership shows that in some cases, US companies can become more competitive by partnering with companies based in other countries. It also comes on top of GM committing tens of billions of dollars to EV development and production, including transitioning several of its assembly plants to EVs7 and partnering with suppliers to ensure it has the raw materials needed to maintain production.8 As GM CEO Mary Barra wrote in 2020, “EVs—and the technology we’re engineering to create them—are key to the growth trajectory at GM. I believe with all the assets we have, we will win.”9 As a result of these investments and the company’s commitment to go all-electric by 2035, GM has become one of the leading sellers of EVs in the United States.10

Additionally, the federal government should continue leveraging existing financing programs within DOE, including the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing (ATVM) direct loan program, to scale up battery manufacturing. The Inflation Reduction Act provided DOE with an additional $3 billion to support the cost of lending for manufacturing of a variety of clean vehicles and components. In 2022, DOE announced its first loan in over a decade that uses the ATVM lending authority: the Syrah Vidalia plant in Louisiana will use a $102 million loan to expand its facility in Louisiana producing graphite-based active anode material, which is a critical component of lithium-ion batteries. DOE has also announced a conditional loan of $2.5 billion for Ultium Cells to manufacture lithium-ion batteries at new facilities in Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee.

To ensure we can get the most out of this program and other opportunities created or bolstered by recent legislation, DOE should release guidance explaining how programs like ATVM can be used in combination with newly available federal tax incentives, such as the aforementioned 45X credit for battery manufacturing, so companies are aware of their options. DOE should also break down any silos that exist between offices to foster better information sharing with industry. For example, the new Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains should share information with the Loan Programs Office (LPO), which runs ATVM, regarding grant applications to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s $3 billion battery manufacturing program; this will enable LPO to reach out to grant applicants that were not selected for awards and tell them about other opportunities, like ATVM, that can help these companies proceed with building out US-based projects.

OEM

The US is a leader in EV OEM, home to a set of legacy automakers making big moves toward EVs and several EV-specific startups. To maintain this leadership, we need to ensure our automakers can continue to provide a desirable vehicle at a competitive price point while scaling up quickly to meet growing demand. And the market opportunity is tremendous: EV OEM has the highest cumulative SAM ($27 trillion) of any segment across the technologies BCG looked at. It also ranks highest for job creation potential, representing 5.7 million jobs during the 2020-2050 period; we can maximize how many of these jobs get filled by American workers by ensuring our OEMs are positioned to capture as much of this market as possible. The EV consumer tax credit, as mentioned in the Technology-Wide section, will be particularly important for helping OEMs achieve economies of scale and compete with foreign EV makers, but there are additional policies that will help maintain and grow our competitive advantage.

Ford

Ford is an electric vehicle success story, thanks to both federal support and private investment. In 2009, the legacy automaker took out a $5.9 billion loan from the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office to retool 13 facilities across the country to make hybrid and electric vehicles, creating and preserving over 33,000 jobs.11 Fast forward a decade later, and Ford is one of the leading sellers of EVs in the United States.12 As Ford CEO Jim Farley said at a press event in August, “We’re really on a mission at Ford to lead an electric and digital revolution for many, not few. And I have to say the shining light for us at Ford is this beautiful Lightning made right down the road in Dearborn, right here in the state of Michigan, already the leader of all EV pickup trucks in our industry in the United States.”13

Ford is investing in the entire EV supply chain, including securing the supply of lithium and other raw materials it needs to maintain production of its EVs in the coming years.14 The company is also partnering with battery supplier SK Innovation to build lithium-ion battery plants and a battery recycling center in Kentucky, creating nearly 11,000 jobs producing EVs and batteries.15 In addition to these private sector efforts, investments in EV battery production and critical material processing in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act will help ensure we have a reliable, secure supply chain for these vehicles.

Continue scaling up manufacturing assistance: OEMs are retooling for EV production but are being outflanked by foreign competitors who are getting more support from their own governments. The US government should leverage existing and new public funding and financing programs to provide OEMs with the support they need in the short-term to build and grow a durable competitive advantage. The US already has some programs in place, such as the ATVM loan program which helps automakers and other manufacturers in the value chain retool for EV production or build new facilities. Congress provided additional assistance through the Inflation Reduction Act, including $2 billion in Domestic Manufacturing Conversion Grants which OEMs can use to retool their facilities for EVs and the 48C Manufacturing Tax Credit. However, we still lag China and Europe, with Chinese investments outpacing the US by roughly 50% over the past four years. To help us catch up, Congress should be prepared to provide additional funding for these programs.

Georgia has a proven record of investing early in the resources and infrastructure needed to connect it to the world and develop jobs of the future. The Electric Mobility and Innovation Alliance will ensure that our state is positioned to continue leading the nation in the rapidly growing electric mobility industry.

-Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp announcing a new initiative to position Georgia as a national leader in the EV supply chain

I’m amazed at the work being done right here in Commerce, Georgia at SK Innovation. They’re paving the way for a greener tomorrow by producing electric car batteries that will power electric vehicles, reduce carbon emissions & fight climate change.

-Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) visiting SK Innovation’s new battery plant

Accelerate federal procurement: The federal fleet includes roughly 193,000 light-duty vehicles, according to the General Services Administration’s (GSA) 2021 Federal Fleet Report; fewer than 2,000 of these are electric. The Biden Administration has directed that each agency’s light-duty vehicle acquisitions must be 100% zero-emission vehicles by 2027.16 An aggressive target for transitioning the federal fleet to EVs will create additional demand for these vehicles, which will help automakers achieve economies of scale and reduce costs. Congress should provide funding to the GSA and other federal agencies to cover the incremental cost of purchasing EVs and EV infrastructure instead of gas-powered vehicles; the GSA can also use funds from its revolving fund, the Acquisition Services Fund (ASF), to cover the incremental costs.17

Build out EV infrastructure: Key to getting more EVs on the road and helping OEMs achieve economies of scale is ensuring we have deployed the public EV chargers needed for people to feel comfortable buying an EV. Congress included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as much as $7.5 billion in grants for EV charger deployment, including $5 billion in formula funds for every state to install DC fast charging stations along highway corridors. Through the IRA, Congress also extended and expanded the 30C tax credit for EV charging and other alternative fueling properties, which will help individuals install EV chargers at their homes and businesses install this infrastructure on their property. Continuing to invest in the buildout of a nationwide charging network will help justify additional investment in domestic manufacturing capacity.

Develop the EV workforce: BCG identified that the US has a competitive edge in technical leadership, one of the key dimensions of the OEM segment. The US auto industry benefits from a well-trained auto workforce, and maintaining this advantage as we shift to EVs will require retraining the workforce to assemble the powertrains and vehicles of the future. Specifically, we need to do so in a way that supports equity and preserves job quality, including good wages and the ability for workers to engage in collective action. To transition the industry in a way that protects and grows good-paying domestic jobs, the US should launch retraining programs for auto production and maintenance workers, including working with schools and registered apprenticeship programs to upskill the workforce around EV-specific capabilities such as battery engineering and powertrain production. This should include support specifically for retraining and placing dislocated and disadvantaged workers in quality jobs along the EV value chain.18

Software development and aftersales services

While software development and aftersales services are separate segments on the value chain, they are inextricably linked and so we consider them together here. These segments include the development and deployment of infotainment, performance and maintenance analytics, and advanced car features such as advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), autonomous vehicles (AV), and connected vehicles. These features are becoming increasingly important for consumers as they consider what vehicle to buy, and the potential market size is large: after-sales services in particular had the second-highest cumulative SAM of any value chain segment assessed by BCG, at $9.2 trillion, while software development came in at $4 trillion. The US is expected to be the largest single market for after-sales services, representing over 40% of the global market. BCG has projected nearly 2.5 million jobs in the aftersales services segment during the 2020-2050 period; capturing this market share means securing the greatest share possible of these jobs for American workers.

BCG assessed that the US has a strong competitive lead in both of these segments, particularly around autonomous and connected vehicle technologies. There is also a high concentration of software developers and aftersales service providers in the US and a lot of private sector investment coming in, giving the US the most mature market globally for these technologies. It will be important that we defend this advantage in the coming decades, particularly as competitors in East Asia grow into the AV market. Ongoing diplomatic efforts to ensure the cybersecurity of electric and automated vehicles will be critically important as we work with our trading partners to bolster this market.19

Invest in RD&D of new vehicle technologies: Consumers increasingly expect their vehicles to have next-generation technologies such as advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) and other technologies enabling higher levels of driving automation. Several federal agencies, including the Federal Highways Administration and DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office, provide federal funding to help the private sector and academic institutions develop and test advanced vehicle technologies; boosted funding will help accelerate these efforts and ensure these next-generation technologies are invented and produced in the US. This funding should come with appropriate oversight to ensure safety always remains a priority as increasingly automated vehicles are tested and brought to market.

Raw materials

The global transition to EVs will drive a massive growth in demand for battery minerals such as lithium, nickel, graphite, cobalt, and copper. As it stands today, the battery mineral supply chain is highly concentrated. China owns much of the world’s critical material processing including over half of the lithium processing, 70% of cobalt processing, and nearly 75% of graphite processing; it also controls nearly all of the world’s graphite production and a significant amount of the lithium production.20

As a result of the low potential for the US to gain a competitive advantage, BCG does not consider this a high-priority value chain segment. However, given how important the critical mineral supply is for the EV supply chain and the risk of becoming wholly dependent on China for these minerals, it is essential that the US take steps, in partnership with our allies, to shore up our access to these minerals and avoid losing more ground. The Biden Administration’s invocation of the Defense Production Act to produce and procure critical battery minerals, as well as funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and tax incentives in the IRA to boost domestic mineral processing and battery production, are significant steps in the right direction.

Streamline permitting processes: The US is hampered by the lack of a streamlined regulatory environment, which inhibits the start of new mining and extraction operations. If we are to shore up domestic raw material production, we need to reduce the length of time it takes to approve a new extraction site, which is far greater in the US than in countries with similar environmental standards (7-10 years in the US for permit approval, compared to 2-3 years in Australia and Canada, according to BCG21). The US should standardize and streamline its permitting processes for mineral extraction and processing, with a focus on minerals most likely to be needed for future battery chemistries, like lithium. This will be particularly important in the coming years as the critical materials requirements for the EV tax credit ramp up: if automakers aren’t able to source these minerals at home or from partner countries, their vehicles will not be eligible for the credit which will dampen demand for these vehicles.

One possible avenue for accelerating permitting approval without sacrificing environmental protection is FAST-41, which was created by Congress in the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. FAST-41 is designed to improve coordination among government agencies and increase transparency using project-specific timetables; it does not alter any environmental or other requirements.22 In January 2021, the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council published a final rule adding mining to the list of statutory FAST-41 sectors,23[xxiii] but to date no proposed mining operations have been selected. As Congress considers a possible permitting reform package, it should be sure to include critical mineral extraction in any policies that would help get these projects approved more quickly while maintaining rigorous environmental protections.

Support battery recycling: Battery recycling provides us with the opportunity to harvest and reuse minerals from batteries that have reached the end of their lives, thereby reducing the amount of new raw materials we need to extract from the ground. While battery recycling is not yet at commercial scale, researchers have projected that we could meet as much as 18% of the cobalt demand, 11% of lithium demand, and 17% of nickel demand by 2035. In addition to the funding provided by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for battery recycling, Congress should boost funding for ReCell, the Department of Energy’s advanced battery recycling R&D center. This initiative will help develop and scale up a globally competitive battery recycling industry that reduces our dependence on battery materials sourced from other countries.

Increase cooperation with trading partners: While the US has significant lithium brine reserves as well as small amounts of cobalt and nickel reserves, it is unlikely that we can extract enough of these minerals domestically to fulfill demand. The US should work with other countries with which we have free trade agreements to ensure we have a supply of critical minerals that isn’t wholly reliant on our adversaries. This could include working within the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to secure Mexican zinc and lithium and Canadian nickel, as well as with our partners in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) which include Indonesia, the largest nickel producer in the world; Australia, which is the largest producer of lithium and which also produces nickel and cobalt; and the Philippines, which is a major producer of nickel, among others.

Cooperation could take the form of technical assistance and capacity building; the creation of incentives for greater trade of critical minerals; and better mapping and assessment of the supply of and demand for these minerals and of the infrastructure, regulatory, and workforce needs to meet demand. In addition to boosting our access to minerals extracted in these countries, the US should seek to develop agreements with other countries to process foreign raw materials in the US.

Impacts from Policy Recommendations

As one of the most mature technologies of those BCG assessed, EVs present the largest market opportunity—but the size of that market depends on how quickly the international community moves towards electrification and decarbonization.

How much of this market the US can capture depends on whether we put the right policies in place now to build the domestic supply chain, regulatory framework, and technical leadership needed to create a durable competitive advantage. The aforementioned policy recommendations are likely to be expensive, but this cost will be more than outweighed by the benefits: higher global market share, job creation, tax revenue, and emissions abatement.

Growing our market share across the EV value chain means creating jobs for American workers, and BCG’s analysis found that EVs are responsible for almost half of all cumulative job gains across technologies. As a result of having the largest projected market share of any technology, and because of the high job creation potential, EVs also have the highest tax revenue potential. BCG assessed, for example, that the OEM segment could generate as much as $189 billion in revenue through 2050 and that after-sales services could generate as much as $141 billion.

Lastly, EVs are well-positioned to contribute to our net-zero climate goals. BCG analysis found that the transition to EVs could unlock five to seven gigatons per year of abatement potential (CO2 equivalent) by 2050, making it one of the heavy hitters for emissions reduction.