DMV: Another Example of Racial and Ethnic Inequity from COVID-19

Cases of the coronavirus are rapidly increasing in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) region, recently surpassing 70,000.1 But not all areas have been affected the same, as the country has seen the coronavirus spread along racial, ethnic, and economic lines. We recently wrote about coronavirus cases decimating racially diverse communities of all sizes—unfortunately, this trend appears particularly stark in the DMV region.

In the District:

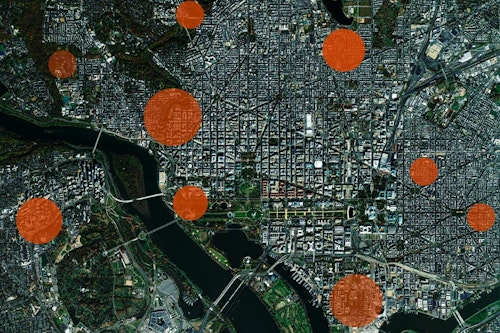

Coronavirus cases are spreading unevenly among D.C.’s eight wards. Wards that are more white, more educated, and have higher median incomes are seeing fewer coronavirus cases per capita than poorer and more diverse wards. Mapping coronavirus cases per capita onto residential demography in D.C. reveals a stark visual trend—higher shares of Black residents in D.C. tend to pair with higher levels of the coronavirus per capita.

D.C. government is reporting disturbing racial disparity data in terms of individual cases and deaths reported as well. Of D.C.’s 6,700 cases reported as of May 13th, 47% are identified as black and only 16% are identified as white. D.C.’s broader demographic makeup is about 45% Black and 42% white.2

D.C. has a large Black share of the population, but unfortunately, coronavirus disparities are not limited to D.C.’s Black community. D.C.’s health department is reporting that Latinos, a relatively small share of the population, are experiencing the highest per capita infection rate of any racial or ethnic minority group.3 D.C. residents in the hardest-hit neighborhoods and wards likely work in frontline essential capacities or live in large family homes, making coronavirus infection and spread likely.

In Maryland & Virginia:

Maryland is home to two D.C.-adjacent counties that are experiencing the coronavirus epidemic very differently. Prince George’s County contains 15% of Maryland’s population but makes up a quarter of its coronavirus cases.4 Its immediate neighbor, Montgomery County, has over 40 cases less per capita.

Prince George’s County is also one of the wealthiest majority-Black counties in the United States. It has been hit far harder than Montgomery County, which has a median household income of over $108,000/year, dwarfing the national median income of $61,000.5 Prince George’s County has over three times the proportion of Black residents and a median household income of $83,000—still notably higher than the national median income.

Prince George’s County also has higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension than state and national averages—a confounding factor in disproportionate health outcomes in the community.6 Access to primary care is also a barrier in Prince George’s County, which has less than 500 primary care physicians in total. Neighboring Montgomery County has over 1,400 primary care physicians despite having 20% less residents.7

Past the District and across the river, counties in Northern Virginia aren’t experiencing the same level of devastation from the coronavirus. While Prince George’s County and Montgomery County are experiencing about 115 and 71 cases per 10,000 residents respectively, Fairfax County, Virginia has about 60 cases per 10,000. Falls Church, Alexandria, and Fairfax County all have more white-identifying residents than their Maryland and D.C. neighbors, they all have fewer Coronavirus cases per capita.

Across the DMV region, the Coronavirus is escalating intensely along existing racial, ethnic, and class divisions. Areas with higher household incomes tend to work in professions that allow remote work and can afford larger living spaces, making precautionary social distancing easier. The DMV region is a hub of racial and ethnic diversity. It is alarming to see this hallmark of the DMV region turned on its head in light of a crippling pandemic.

Endnotes

Jouvenal, Justin and Hedgpeth, Dana. "Va. governor says state could start reopenign on May 15." The Washington Post, 4 May 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2020/05/04/coronavirus-dc-maryland-virginia-live-updates/#link-BFH2RIMSNFFZDA52ODEFIWRY7Y. Accessed May 14, 2020.

"Coronavirus Data." The Government of the District of Columbia, 13 May 2020. https://coronavirus.dc.gov/page/coronavirus-data. Accessed May 14, 2020.

Jouvenal, Justin and Hedgpeth, Dana. "Va. governor says state could start reopenign on May 15." The Washington Post, 4 May 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2020/05/04/coronavirus-dc-maryland-virginia-live-updates/#link-BFH2RIMSNFFZDA52ODEFIWRY7Y. Accessed May 14, 2020.

Chason, Rachel. "Hospitals in Prince George's seeing an influx of critically ill coronavirus patients." The Washington Post, 14 Apr. 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/prince-georges-hospitals-coronavirus-crisis/2020/04/14/2ac05724-7e7f-11ea-9040-68981f488eed_story.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

"Montgomery County, MD" Covid-19 In Numbers, May 2020. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/montgomery-county-md. Accessed May 14, 2020.

Chason, Rachel et al. "Covid-19 is ravaging one of the country's wealthiest black counties." The Washington Post, 26 Apr. 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/prince-georges-maryland-coronavirus-health-disparities/2020/04/26/0f120788-82f9-11ea-ae26-989cfce1c7c7_story.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

"Maryland" County Health Rankings, A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/maryland/2018/measure/factors/4/data. Accessed May 14, 2020.

Subscribe

Get updates whenever new content is added. We'll never share your email with anyone.