A Lesson from the Deep Blue Northeast

2018 was a wave election for Democrats, with the Party picking up House seats and governors’ mansions in purple and even red districts and states. Nearly all research appears to agree that it was a combination of turning out infrequent voters and persuading swing voters; however, there are still some disagreements about why. Some are arguing, largely without evidence, that it was full-throated far-left populism that delivered the goods in those flipped seats. We’ve noted elsewhere that this is completely wrong—the nominees in most of those races were mainstream or moderate Democrats. Still, in a trio of governors races in cobalt blue states (Maryland, Massachusetts, and Vermont), there were some pretty leftwing candidates on the ballot in November.

So how’d they do? Not very well.

These races were important, because they tested the notion, proposed by some activists last summer, that turnout would deliver a Democratic majority and that swing voters could be ignored. They posited that if Democrats nominated true leftwing progressives, a group of low-propensity voters would be motivated to turn out, and by their numbers alone, deliver victories. By that logic, the candidates in those three states should have been turnout machines.

But they were not. All three lost. To be clear, we are not arguing that mainstream Democrats would have won those races—all were uphill battles against popular Republican incumbents. But the data from these states show why the far left’s turnout theory falls far short.

The Candidates

Ben Jealous in Maryland, Jay Gonzalez in Massachusetts, and Christine Hallquist in Vermont all made clear they were running as far-left candidates.

Jealous and Hallquist were the only two gubernatorial candidates in the country who won their primaries with the backing of far-left Justice Democrats. Gonzalez was more establishment, and he actually beat an Our Revolution candidate in the primary. But he ran a leftwing general election campaign focused on single-payer state healthcare and other items on the far-left wish list.

These three Democrats were running against Govs. Charlie Baker (MA), Larry Hogan (MD), and Phil Scott (VT). According to polling before the general elections, Baker and Hogan were the most popular governors in the country, sporting 70% and 67% approval ratings, respectively. Phil Scott’s rating was only 50%, but he had high approvals with Independents and Democrats (and not necessarily universal support among Republicans). So Scott was well situated to win a general election even though he turned in a lackluster primary victory against a total unknown with neither money nor campaign infrastructure.

The States

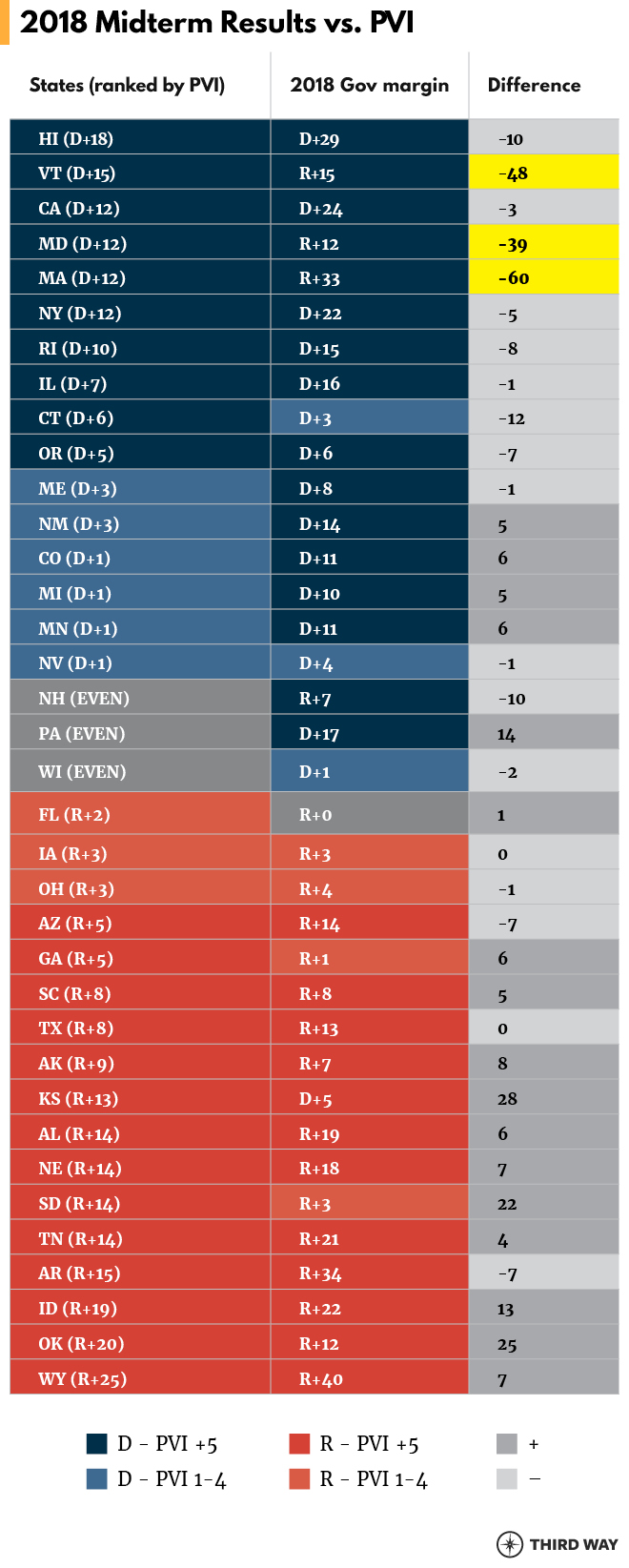

Based on Cook Political Report’s partisan voter index (PVI), Maryland, Massachusetts, and Vermont are among most Democratic states in the country. This measure is based on how the states voted in the last two presidential elections against an average pegged to the national popular vote. VT is the second most Democratic at D+15 (meaning it voted on average 15 points more Democratic than the country as a whole), and MD and MA are in a four-way tie for third at D+12. These three states are now the only in the country that vote more Democratic than the national average but still have Republican governors. If the turnout theory could work anywhere, it should’ve been able to work here.

The Results

Turnout was up across the board in 2018—historically high for a midterm election. And these three states had higher turnout than the national average in the last four midterms. So while 2018 set national midterm records for this century, so did the midterm turnout in these three states.

However, in two out of three (MD and MA), the turnout advantage compared to national levels was at its lowest this century. In the third—VT—turnout versus the national average was basically the same in 2014 and 2018. Lots of voters showed up in 2018 that you wouldn’t normally expect in a midterm, but they turned out to push back against Donald Trump, just as they did across the country. There was no big uptick in turnout for these three champions of the left, even in these deep blue places.

In fact, when controlling for PVI, these three gubernatorial candidates turned in the worst performances in the country. Again, that is not to say a mainstream Democratic candidate could have won against someone as popular as these three governors. But mainstream Democrat Molly Kelly—an Emily’s List favorite—did much better in nearby New Hampshire against a similarly popular incumbent.

And it is important to note one more pattern. Since PVI measures federal contests, Democratic candidates in blue states almost always underperform PVI, and Democratic candidates in red states almost always over-perform PVI, because they are often less partisan than federal ones. But popular moderate Northeastern Governors like Andrew Cuomo (NY), Gina Raimondo (RI) had relatively mild underperformances of less than 10 points compared to PVI while the far left candidates in neighboring states underperformed by around 40 to 60 points. So there is little evidence that leftwing candidates are more likely to win because they can excite irregular voters. Instead, all three of these far-left candidates saw Democratic voters in their deep blue states pull the lever for the Republican.

Conclusion

The 2018 midterms show once again that turnout and persuasion are both key to Democratic victories. But the fantasy that running far-left candidates will unearth a hidden trove of disillusioned progressives to appear at the polls and deliver victory without the help of persuading swing voters, crashed against the rocks in this year’s blue wave.