Memo Published June 25, 2025 · 7 minute read

340B Hospitals are Lacking on Charity Care

Blair Elliott & Darbin Wofford

More than six-in-ten US hospitals benefit from a little-known program called the 340B Drug Pricing Program. The program requires drug manufacturers to provide discounted medicines to qualified providers, which can help patients access cheaper medicines that would otherwise be unobtainable. It’s an essential tool for low-income patients.

The problem is that patients often do not see a direct benefit from the program. Most 340B hospitals are not required to pass on drug discounts to patients, meaning they can charge patients full price for a discounted drug and keep the difference. If patients aren’t going to see savings, the hope would be that hospitals would at least put 340B profits toward charity care for low-income patients. In practice, however, many hospitals use their 340B profits for other purposes, spend very little on charity care, and even aggressively pursue patients for debt collection.

In this memo, we briefly explain the 340B program, unpack where charity care is lacking, and demonstrate why improvements to transparency and accountability are essential to ensuring the program fulfills its promise to vulnerable patients.

What is 340B?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program was created in 1992 to help health care providers treat low-income patients. As a result of 340B, non-profit hospitals and other providers who are enrolled in the program, like community health centers and Ryan White HIV/AIDS clinics, can purchase drugs at a discounted cost so that low-income patients can access the medicine they need at an affordable price. Struggling hospitals that serve rural or low-income communities can also leverage 340B funds to make ends meet.

While the program serves an important purpose, unchecked growth in the number of participating hospitals in recent years has led to a distortion of 340B’s original purpose. More than 2,600 hospitals—over 40% of all US hospitals—are now enrolled in the program. In 2023, more than $66 billion in drugs were purchased through the 340B program, a 24% increase compared to 2022. Nearly 90% of those purchases were made by hospitals. To put that number in perspective, $66 billion is more than the government spent on drugs for the 72 million Americans enrolled in Medicaid.

Certain providers—such as community health centers and Ryan White clinics—are required by law to use discounts to benefit patients. Most hospitals in the program, however, are under no such obligation. For instance, Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH), which serve larger shares of Medicaid and uninsured patients, bring in about 80% of total 340B revenue, yet are not required to use 340B profits to benefit their patients.

For a more detailed overview of the 340B Drug Pricing Program, click here.

340B Hospitals & Charity Care

Without defined rules governing how 340B discounts can be used, 340B hospitals are free to use program profits however they like. And the evidence is clear: 340B hospitals are choosing to spend very little on charity care, leaving an ever-growing number of vulnerable patients unprotected.

In 47 states and DC, more than half of the DSH hospitals in the program brought in more 340B revenue than they spent on charity care. What’s more, over two-thirds of 340B DSH hospitals provide less charity care than the national average, and more than one-third spend less than 1% of their annual revenue on charity care.

For example, New York City’s NYU Langone Health hospital benefits from the 340B program, yet spent less than 0.34% of their $7.2 billion in annual revenue on charity care. Instead, they spent $8 million running a Superbowl ad. And the Cleveland Clinic brought in over $900 million in 340B profits in just over three years from April 2020 to June 2023. These savings were not passed on directly to patients and were instead lumped into the hospital system’s overall revenue. In response to an investigation by the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, Bon Secours Mercy Health, a large hospital chain with over 50 hospitals, stated “revenue is revenue” when asked how it uses revenue derived from the 340B program.

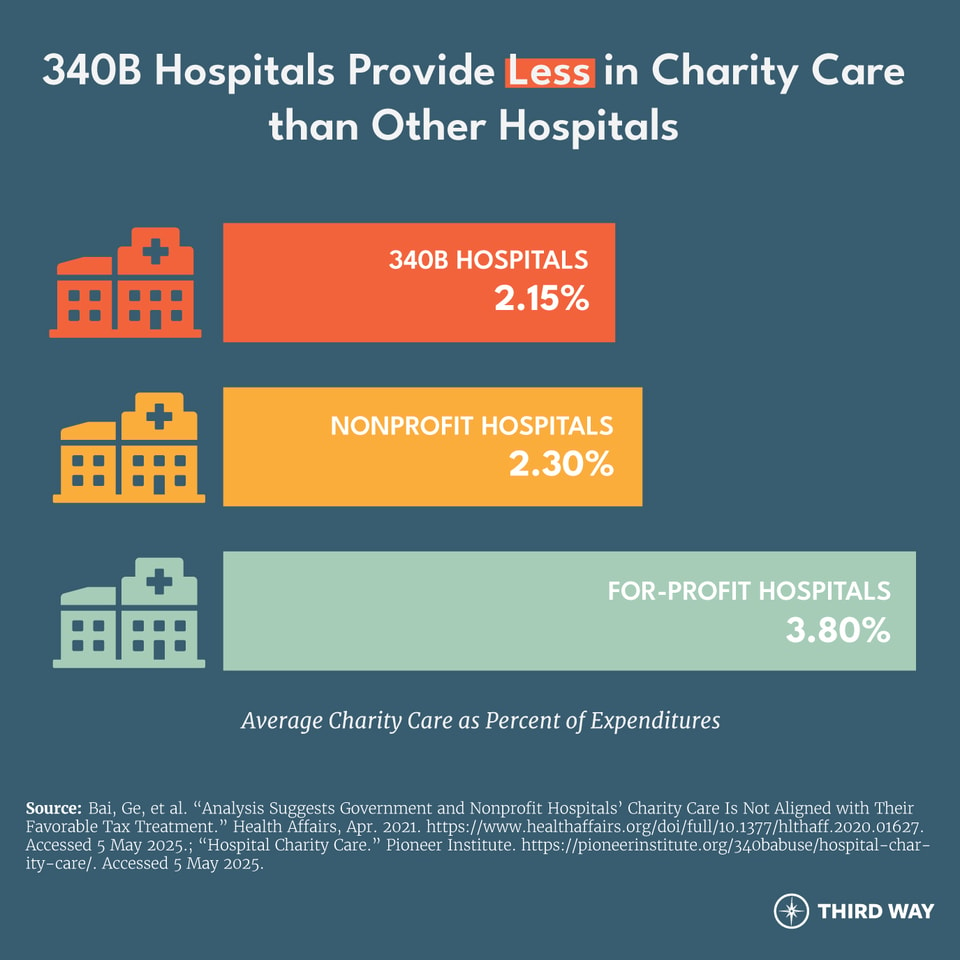

Evidence also demonstrates that hospitals in the 340B program provide less charity care than their non-340B counterparts. As shown in the chart below, 340B hospitals provide less charity care than all nonprofit hospitals and almost half as much as for-profit hospitals.

In addition to providing low levels of charity care to the patients who need it most, some 340B hospitals pursue aggressive debt collection practices against patients struggling to repay expensive medical bills. A systematic review of the financial assistance policies of 75 of the nation’s largest 340B hospitals revealed that only six of those hospitals explicitly prohibited the use of extraordinary debt collections actions, which can range from denying non-emergent care to those with outstanding bills to taking patients to court.

For example, the 340B-participating University of Arkansas Medical Sciences hospital system sued more than 8,000 patients between 2019 and 2023 for unpaid medical bills. In 2016, the system sued just 35 patients; however, by 2021, they filed 3,000 suits in that year alone. Hundreds of the sued patients were even employees of the hospital system.

The Solution: Putting Patients First in 340B

The 340B program is an essential tool to support health care providers and the patients they serve. But requirements need clarity on how hospitals can use 340B discounts. To ensure low-income and uninsured patients can afford the prescriptions they need to survive, lawmakers should improve 340B in three key ways:

First, require hospitals and their affiliated clinics to make 340B prescriptions affordable for vulnerable patients and provide baseline levels of charity care. This is already a requirement for federal grantees, such as community health centers, but not for all participating providers. Currently, federal grantees charge patients based on a sliding income scale, so patients with the lowest incomes can purchase their prescriptions at an affordable price. This by no means eliminates hospitals’ access to discounted drugs—it simply ensures patients see some of the benefits. The 340B Affording Care for Communities & Ensuring a Strong Safety-Net (ACCESS) Act, legislation introduced last year by Representatives Larry Bucshon (R-IN), Buddy Carter (R-GA), and Diana Harshbarger (R-TN), would require all 340B hospitals to provide discounted medicines to patients on a sliding scale based on their income levels.

The ACCESS Act would also require that participating DSH hospitals spend the same or more on charity care as they receive in 340B savings. DSH hospitals that failed to meet that standard could be disenrolled from the program until they could demonstrate increased spending on charity care.

Second, strengthen eligibility standards for participating hospitals. The rapid growth of enrollment in the 340B program has meant that many participating 340B hospitals already have healthy profit margins. The 340B ACCESS Act would create more stringent standards for eligibility to ensure that 340B dollars are directed toward the hospitals and communities that need them most. Specifically, the legislation would require certain hospitals to have a share of Medicaid and CHIP revenue and uncompensated care cost in the top 40% of hospitals in the country in order to enroll in the program.

Third, ban the use of aggressive medical debt collection by 340B providers. Hospitals serving low-income patients in vulnerable communities should never go after patients through aggressive and hostile tactics. These protections are also included in the 340B ACCESS Act, which would ban what’s called extraordinary collections. This term, as defined by the IRS, includes suing patients for unpaid medical debt, placing liens on patients’ properties, or garnishing their wages.

Conclusion

The 340B program is critical to ensuring that low-income patients have access to the drugs they need. However, as it currently functions, the rapidly expanding program provides no guardrails to ensure 340B dollars actually benefit patients. Patients who cannot afford care can still find themselves saddled with large bills and become victims of aggressive debt collection. Requirements for hospitals to pass drug discounts on to low-income patients and bans on aggressive debt collection for 340B providers would play a key role in fixing this broken system.