Third Way Take Published May 5, 2016 · Updated May 5, 2016 · 6 minute read

A Closer Look at Market Consolidation in Banking

Emily Liner & Paul Lapointe

Anyone even remotely paying attention knows that the banking industry is consolidating. The statistics are very clear—there are fewer banks today (5,309 as of the end of 2015) than there were in the past (14,400 as of 1984, a commonly used benchmark).

When economists, politicians, and candidates talk about this issue, they tend to focus on whether or not this trend is bad for financial stability. “Break up the banks” proponents focus on the big banks being "too big to fail", while others argue that it is not size but the riskiness of activity and interconnectedness that we should worry about. Although these arguments about financial stability constitute an important policy debate, there is another reason banking consolidation might matter.

When markets concentrate, it can sometimes hurt competition and, ultimately, consumers. If there is little competition in an industry, the remaining firms can have excessive market power, allowing them to extract outsized profits at the expense of their customers.

So is this happening in the banking industry? Are customers being squeezed by fewer and fewer large banks?

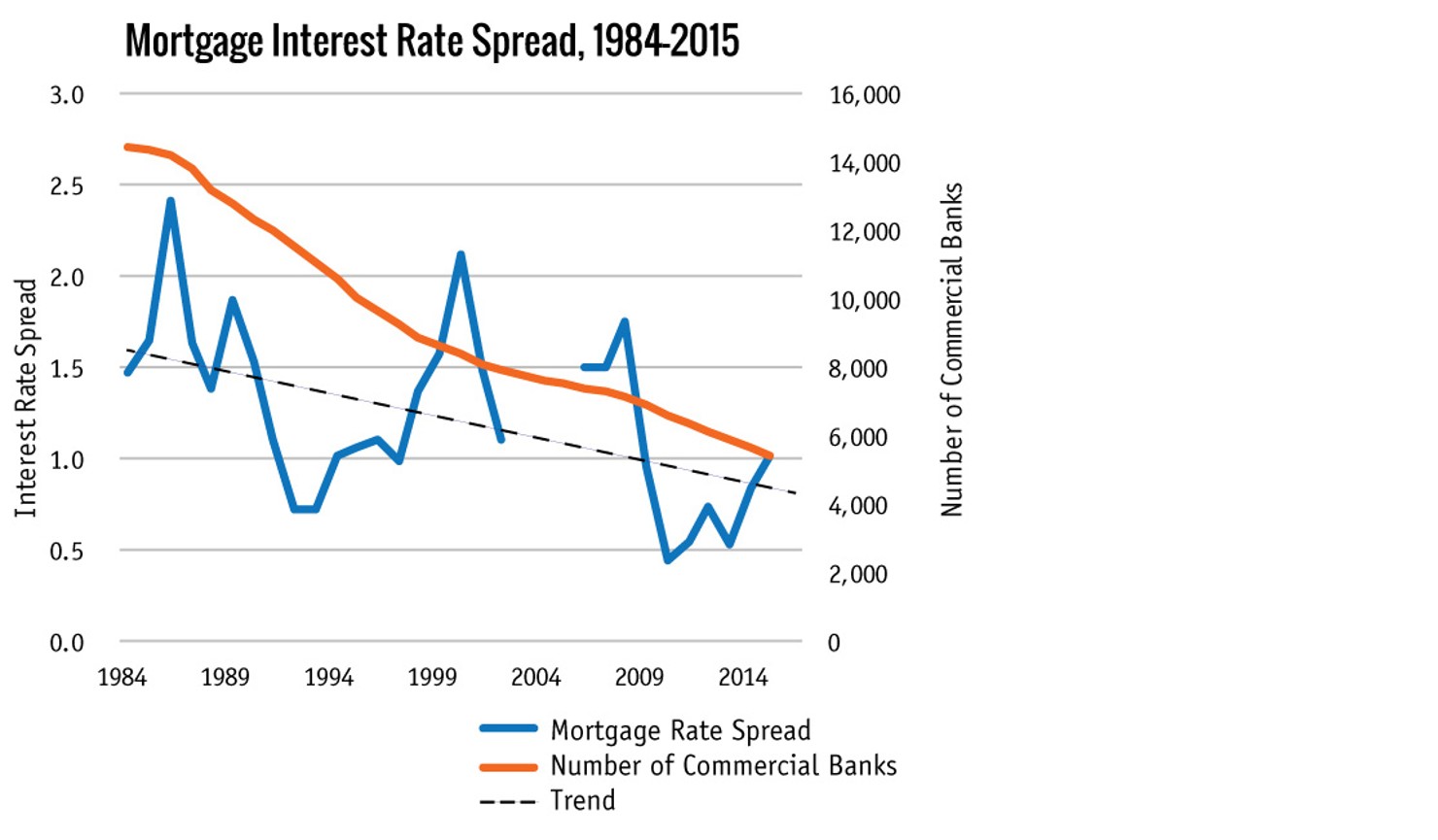

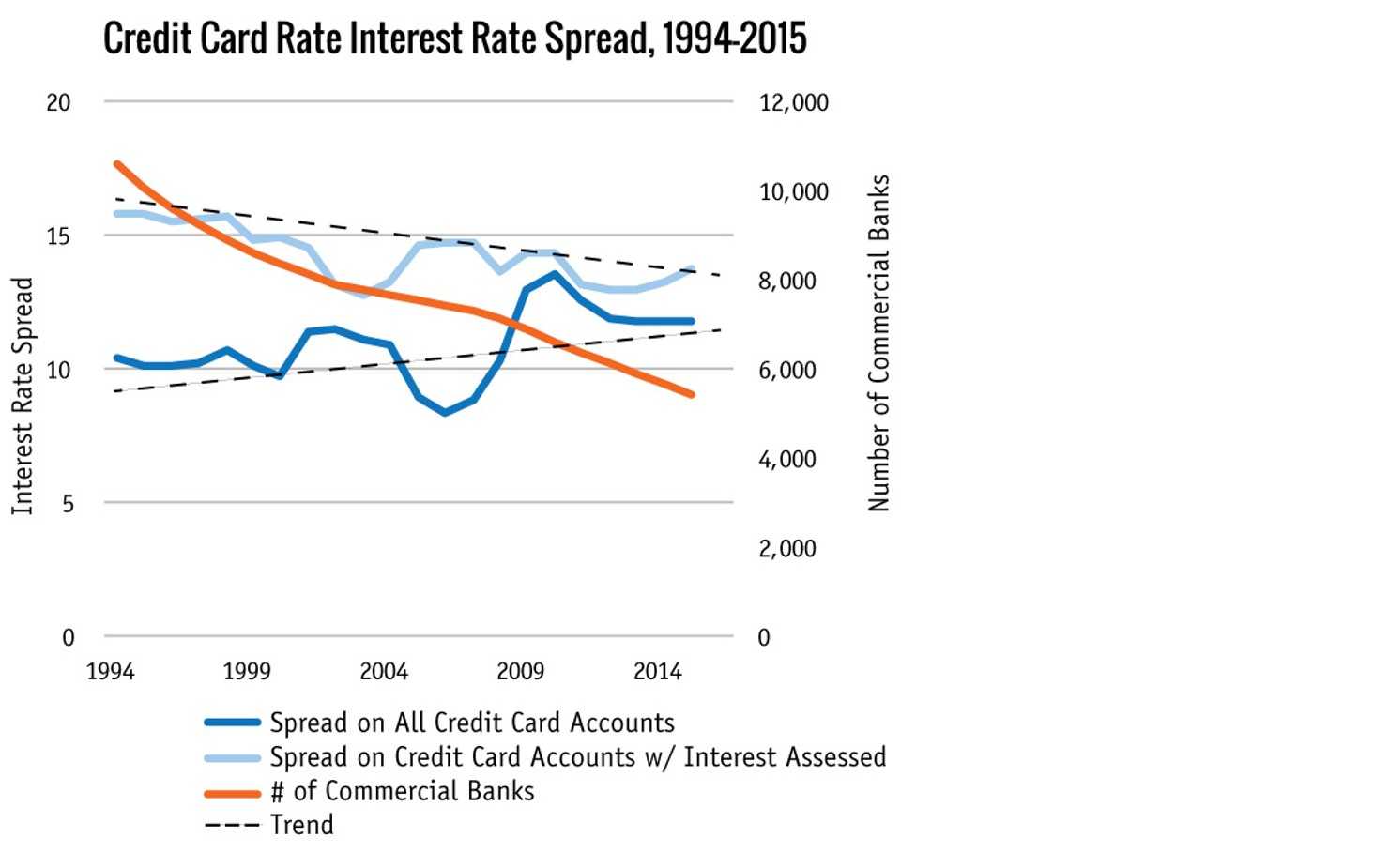

We looked at two of the most common consumer loans to see whether banking consolidation is having a deleterious impact on the consumer: mortgages and credit cards. Since broader economic conditions are constantly influencing rates, we looked at “spreads,” which is a more objective measurement. This is the difference between the interest rate charged to consumers and a particular benchmark, Treasury securities. We find that consumer credit spreads are not increasing broadly.

The most common type of loan for American families—the 30-year mortgage—is indicative. This chart shows the number of commercial banks in the U.S. and the spread between interest rates on 30-year mortgages and 30-year Treasuries. As banks consolidated, consumer spreads declined. In 1984, the spread was about 1.5%, while in 2015 it was 1.0%. A half-point difference might not seem like much, but over the course of a 30-year fixed rate mortgage for a $200,000 home, it comes to more than $20,000.

We also looked at the spreads on credit cards using 1-year Treasuries as the benchmark interest rate. The darker blue line shows the interest rate on all credit card accounts, while the lighter blue line shows the interest rate just on accounts with interest assessed. While both figures relay important information, the rate on cards with interest rates assessed is more reflective of consumers’ actual experiences.

Here, the average spread on accounts where interest was actually paid has decreased. And while the average overall spread on credit card rates has increased, this upward trend is less likely to be felt by consumers since they are not necessarily paying interest on the accounts.

If banks were consolidating in a way that left consumers with only a few options when they choose where to bank, that would be a problem that would lead to those banks having extraordinary leverage over customers. In reality, that’s not what’s happening.

Generally, firms consolidate to take advantage of economies of scale. This is certainly true in the banking sector. Typically, small companies banding together can lower their total overhead costs by combining shared services, infrastructure, and expertise. In the banking industry, many small banks may find it difficult to conduct daily operations, meet new regulatory requirements, and still justify the costs of services that consumers increasingly expect, like mobile and online banking. While many small banks are successfully meeting these demands, there is an incentive for smaller banks to band together in pursuit of economies of scale.

Indeed, more often than not, consolidation is the result of two small banks merging. A 2014 FDIC report found that, over the past decade, two-thirds of community banks that were acquired were actually purchased by another community bank.

Banks are also getting bigger in order to expand their geographic footprint. The reality is that in this day and age, local banks now compete on a regional scale; regional banks on a national scale; and national banks on a global scale. A company dealing with customers, employees, and offices spread across the country doesn’t want to deal with multiple banks to conduct daily operations. Similarly, multinational businesses want to work with multinational banks. Financial institutions have to keep up with the increasingly global nature of business.

Believe it or not, the U.S. banking system is one of the least concentrated. According to an OECD report, the concentration level of the top three banks in the U.S. is the lowest in the G-7.

Furthermore, Dodd-Frank prevents the biggest banks from getting any bigger than they already are. Under Section 622, banks are prohibited from merging if doing so would create a firm that accounts for more than 10% of the liabilities of the industry. This means that the Big Four won’t be able to become the Big Two or Big One.

Now, it’s true that larger banks have gained a bigger share of the U.S. banking industry. According to the FDIC, banks with more than $10 billion in assets make up 80% of the industry. But that figure captures 109 different banks in the U.S., two-thirds of which are regional banks that are not considered systemically important (or too big to fail). And it doesn’t take into account the increasing competition that traditional banks face from shadow banks and fintech upstarts that now offer many of the same services.

Here’s what else is true: At the same time that the overall number of banks has declined, the overall number of bank branches has increased significantly. There were 82,613 bank branches in the U.S. at the end of 2014—nearly double the 1984 total of 42,717. While some disadvantaged communities still face a lack of banking options, overall, most Americans have easier access to banks.

The “break up the banks” debate is not likely to disappear anytime soon, even though Dodd-Frank put in place significant safety mechanisms to ensure their safety and soundness. As we have these debates, policymakers should keep in mind that bank consolidation does not appear to have created a less competitive marketplace for consumer lending in mortgages and credit cards.