Report Published April 25, 2016 · Updated September 30, 2016 · 16 minute read

Understanding the Terrorism Threat

Sanaa Khan

The threat from terrorism lingers fifteen years after the attacks on 9/11. Recent attacks in Brussels, Ankara, San Bernardino, and Paris have ignited fears across the globe of ISIS’s reach beyond the borders of Iraq and Syria. Although it’s a shadow of its former self, the original terror threat, al Qaeda, still poses a danger to Americans and our allies. Al Qaeda’s affiliate groups in Yemen and across North Africa continue to carry out attacks in their respective regions, often against western interests. These groups continue to threaten the homeland, recruit, and influence attackers beyond the traditional battlefield, and plan attacks in the West. In order for our elected officials to provide effective oversight and evaluate U.S. efforts to combat terrorism, a comprehensive understanding of the terrorism threat is essential.

This primer will provide:

- A background on al Qaeda, ISIS and related terrorist groups;

- The tools they use for recruitment and radicalization; and

- Ongoing U.S. efforts to defeat them.

The Threat From al Qaeda

Background and Ideology

During the decade-long Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, scores of volunteers from across the globe traveled there to join the insurgency against the Soviets. Among them was Osama bin Laden, a wealthy Saudi national who established a fundraising and recruitment network to bring in more fighters. After the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan in 1988, bin Laden used these fighters to found a new Sunni terrorist group called al Qaeda, which he dedicated to overthrowing pro-Western governments in the Arab world.1

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, bin Laden vehemently opposed the decision by the Saudi government to allow U.S. forces into Saudi Arabia. After he turned against the Saudi royal family, bin Laden was expelled from the kingdom. He moved to Sudan and began training al Qaeda fighters for conflicts in the Balkans, Kashmir, and the Philippines. Under pressure from the U.S. and Egypt, Sudan ejected bin Laden in 1996. He returned to Afghanistan, where the new government under the Taliban provided sanctuary for al Qaeda. It was during this time that al Qaeda shifted its focus from governments in the Middle East, the “near enemy,” to the “far enemy” – the U.S.2

Evolution of Attacks

Al Qaeda carried out several terrorist attacks against the U.S. before they became well known on a global scale. Its first attempt to kill U.S. troops was in 1992, when it bombed a hotel in Yemen, killing two Austrian tourists.3 In 1993, two U.S. helicopters were shot down in Somalia and 18 U.S. special operations forces were killed by Somalis trained by al Qaeda. In 1998, bin Laden issued a fatwa – an Islamic decree – calling on his followers to kill Americans around the world. Later that year, al Qaeda carried out one of its largest attacks, bombing the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, and killing about 300 people and injuring thousands.4 In 2000, al Qaeda bombed the USS Cole, a navy destroyer, in the port outside Aden, Yemen, killing 17 American sailors.5

The attacks on September 11, 2001, marked the largest operation ever by al Qaeda, killing nearly 3,000 people. The U.S. named bin Laden and al Qaeda as responsible for the attack, and Congress passed an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), giving the President the authority to attack al Qaeda.6 Operation Enduring Freedom began soon after to take out al Qaeda members and the Taliban – who provided them safe haven – in Afghanistan. This AUMF is still used today to justify U.S. operations against ISIS and al Qaeda groups. NATO invoked its mutual defense clause for the first time, and coalition partners joined the U.S. in attacking al Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

U.S. Efforts to Defeat al Qaeda

In the almost 15 years since the war on terror began, the U.S. has decimated so-called “core” al Qaeda in Afghanistan and the tribal regions of Pakistan. An estimated 20,000 to 35,000 Taliban and insurgent fighters were killed in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom, which ended at the close of 2014. During this time, the U.S. spent an estimated $686 billion on Operation Enduring Freedom to conduct operations in Afghanistan.7 In May 2011, U.S. Navy Seals carried out an operation in Pakistan that killed Osama bin Laden, and Ayman al-Zawahiri was named the new leader of al Qaeda.

In Pakistan, the U.S. has conducted drone strikes against terrorists, killing between 1,500 and 3,500 terrorists8 and carrying out over 400 drone strikes since 2004.9 The U.S. continues to carry out covert drone strikes against terrorists in Pakistan, killing an estimated 60 to 85 in 2015 alone.10 About 8,400 U.S. forces will remain in Afghanistan to train and assist the Afghan National Security Forces. The U.S. also continues counterterrorism operations against insurgent groups in Afghanistan. Last year, U.S. and Afghan forces carried out a joint operation to destroy al Qaeda training grounds.11 Remaining al Qaeda terrorists, however, still aim to attack Americans, and the symbolism of the central organization still inspires supporters.

The Threat from al Qaeda Affiliates

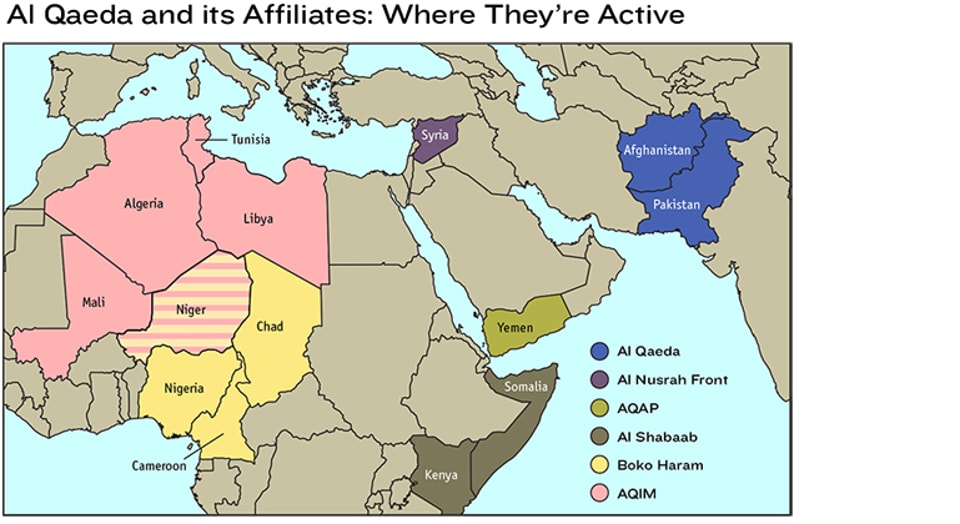

The influence of al Qaeda spawned several other Sunni extremist groups across the region with similarly radical aims. Although these groups generally seek to achieve regional supremacy, they often have international targets in mind. Major al Qaeda affiliates include:

- Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP): Based in Yemen.

- Al Shabaab: Based in Somalia.

- Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM): Based in Algeria and the Sahel.

- Boko Haram: Based in Nigeria.

- Al Nusrah Front: Based in Syria.

The Affiliates

AQAP, which sometimes goes by its alias, Ansar al-Sharia (not to be confused with a Libyan group by the same name), is one of the most lethal al Qaeda affiliates, and one the U.S. government labeled most likely to attempt an attack against the U.S. Like core al Qaeda, AQAP aims to attack the U.S., as well as regional pro-Western governments, like in Yemen and Saudi Arabia.12 It was formed in 2009, combining different branches of al Qaeda in Saudi Arabia and Yemen under one organization. It comprises roughly 1,000 members as of 2015.13 Its most notable attempt at an international attack took place in 2009, when the “Underwear Bomber” tried but failed to detonate a bomb on a flight to Detroit. A year later, intelligence agencies foiled an AQAP plot to hide explosives in printer cartridges bound for the U.S. AQAP has seen much more success inside Yemen, where it conducts frequent car bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations. The group also publishes propaganda in the English-language online magazine, Inspire.

The U.S. has pursued a strategy of taking out AQAP terrorists who pose a threat to the homeland, while working with the Yemeni government to build their capacity to take on the threat. Citing authority provided by the 2001 AUMF against al Qaeda, the U.S. has carried out over 140 airstrikes against AQAP since 2002. These operations have killed 725 AQAP members, including several key leaders.14 In 2011, the U.S. killed Anwar al Awlaki, an American citizen who was an influential recruiter for AQAP. Last summer, AQAP leader Nasir al Wuhayshi was also killed in a U.S. airstrike. In March, the U.S. took out 50 AQAP militants in one strike.15

Al Shabaab is a Somalia-based terrorist group formed in 2006 that focuses its efforts internally, aspiring to create Islamic rule in Somalia. Its leaders share ties with core al Qaeda, and al Shabaab formally joined forces with al Qaeda in 2012.16 The U.S. State Department estimates the group has “several thousand members.”17 Al Shabaab’s activities generally remain confined to Somalia, but the group has launched major attacks in neighboring countries. Al Shabaab was responsible for the 2013 attack on the Westgate Mall in Kenya, which killed 67 people. Last year, al Shabaab militants laid siege to a Kenyan university and killed about 147 people.

The U.S. has concentrated its efforts in Somalia on strengthening African Union forces to fight al Shabaab. In addition, since 2013, the U.S. conducts targeted drone strikes and special operations missions against the group and has stepped up these efforts in recent months. In 2015, U.S. airstrikes killed al Shabaab’s top leaders, including Adnan Garaar and Abdirahman Sandhere.18 This year, U.S. aircraft struck an al Shabaab training camp, killing more than 150 militants, including senior leaders.

AQIM was founded in 2007. They operate primarily out of Algeria, but also in Libya, Tunisia, Mali, and Niger. AQIM aims to remove western influence and establish Islamic law throughout North Africa. Members have increasingly spoken out against the West, and aspire to create an Islamic state. The terrorists who attacked the U.S. facility in Benghazi and killed four Americans, including the U.S. ambassador, were linked to AQIM.

The U.S. provides civilian and military assistance and established the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership in 2005 to counter violent extremism in the region. France’s 2013 intervention in Mali was a setback for AQIM, which has dwindled to “several hundred fighters” in Algeria and across the Sahel.19 As their operations have died down, AQIM has been kidnapping western citizens and holding them for ransom in order to make money.

Boko Haram is a Nigeria-based terrorist group that aims to replace the Nigerian government with Islamic rule, but also conducts operations in the broader region. Its name translates to “western education is forbidden.”20 It was created in 2002, but escalated its attacks following a period of civil unrest in 2009. They promote a violent Sunni extremist ideology, and in 2010 expressed solidarity with al Qaeda and received funding and training from AQIM. In 2014, the U.S. State Department estimated the group had “several thousand” members.21 In recent years, they’ve carried out suicide bombings, assassinations, and kidnappings. Some of Boko Haram’s largest profile attacks in Nigeria were in 2014: they reportedly killed about 5,000 Nigerians and were responsible for the kidnapping of 276 young female students from a school.22 Last year, Boko Haram switched its allegiance to ISIS.23

In 2014, the U.S. sent 80 military advisers to Nigeria following Boko Haram’s school kidnapping. Last fall, 300 U.S. military personnel were deployed to Cameroon to provide regional forces surveillance and intelligence assistance and training against Boko Haram.24 Currently, the Defense Department is planning to send Special Operations forces to Nigeria to assist regional forces in advisory roles.25 The Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, has said that Boko Haram lost territory in 2015, but will continue to pose a threat in Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger, and Chad.26

Al Nusrah Front developed out of the civil war in Syria and was originally linked to ISIS. They declared their intention in 2012 to overthrow the Assad regime from power and set up Sunni Islamic law in its place. Divisions grew between ISIS and al Nusrah and Al Nusrah pledged its allegiance to al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in 2013. Al Nusrah is at war with the Syrian government, and often clashes with ISIS and various Syrian rebel groups.27 Many al Nusrah fighters have defected to ISIS, further revealing strains between the two organizations. Last fall, Zawahiri called for reconciliation between al Nusrah and ISIS, despite viewing ISIS as illegitimate. The U.S. State Department estimates al Nusrah has members in the “low thousands.”28 The U.S. has been targeting al Nusrah in Iraq and Syria since 2014. The U.S. recently conducted an airstrike that hit a senior al Qaeda meeting in Syria, killing 20 al Nusrah terrorists, including their spokesman, Abu Firas al-Suri.29 Over the summer, al Nusrah severed ties with al Qaeda and rebranded the group as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, or "The Levant Conquest Front."

The Rise of ISIS

Al Qaeda in Iraq to ISIS

After the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, a man named Abu Musab al Zarqawi, a former volunteer fighter in Afghanistan in the 1990s, turned his Sunni insurgency group into al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). During the U.S. occupation of Iraq, AQI attacked U.S. forces and exacerbated sectarian divisions by attacking Shia Muslims, the predominant Muslim sect in Iraq – a tactic denounced by core al Qaeda. After U.S. forces killed Zarqawi in 2006, AQI lost momentum. Gradually, other insurgent groups joined AQI and the group rebranded as the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) in the years leading up to the civil unrest in Syria. By 2013, its leaders moved to Syria and changed ISI to the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), referring to the Levant territory that includes Syria.

Al Qaeda leadership preferred its offshoot, al Nusrah, to operate in Syria and had demanded ISIS to leave the country. ISIS moved into Syria despite this demand, and al Qaeda disassociated with ISIS in early 2014. ISIS attacked al Qaeda allies and other rebel groups across Syria. By the summer of 2014, ISIS had expanded territory in Iraq and Syria, using Iraq’s political and sectarian divisions to seize Mosul from Iraqi security forces, in addition to many Sunni-populated lands. Once it acquired control of significant territory, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS, declared ISIS a caliphate – a state that enforces Islamic law. ISIS has also created its own propaganda magazine, Dabiq, to flaunt its successes, lay out its vision, and recruit followers. According to the December 2015 issue of the magazine, ISIS’s goal is to expand the caliphate in the region and eventually across the world - a stark contrast to related terrorist groups that focus on attacking Western targets and regional governments.30

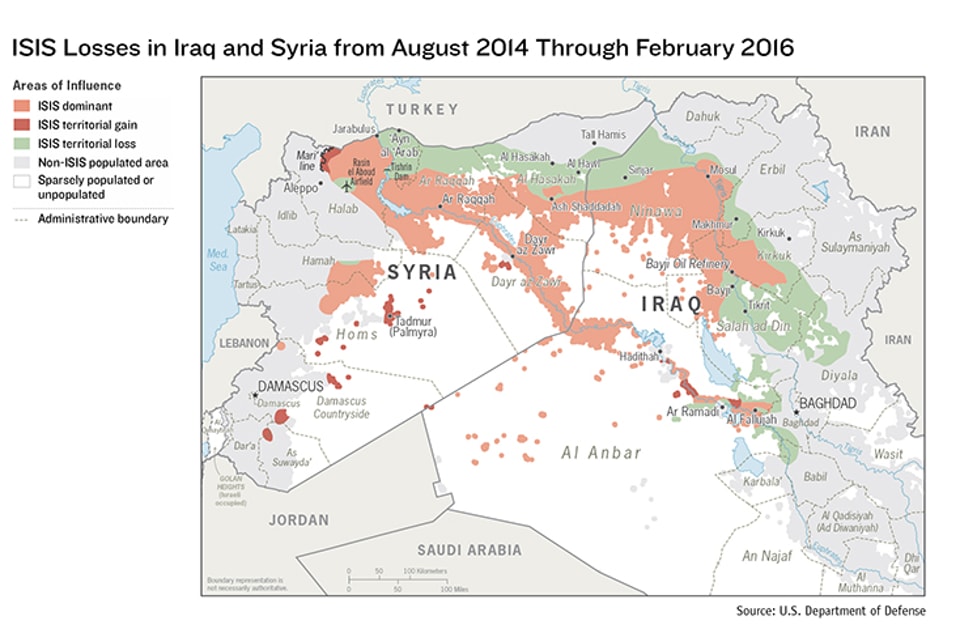

U.S. and Coalition Efforts to Defeat ISIS

Since 2014, the U.S. has led a 66-nation coalition against ISIS, conducting airstrikes against their positions and assisting local ground forces to take back territory. Coalition forces are averaging about 20 airstrikes per day against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, killing more than 45,000 ISIS fighters since 2014.31 In addition, 30,000 ISIS targets, including vehicles, fighting positions, and oil facilities have been destroyed.32 Airstrikes are also taking out ISIS’s finances, with strikes on major ISIS cash depots in Iraq and Syria.33 The group has lost more than 45% of the territory it once held in Iraq, and has lost nearly 25% of the territory it held in Syria.34 The key cities of Ramadi and Tikrit have been retaken by Iraqi forces, and the groundwork is being laid to retake the major city of Mosul. There are currently about 5,000 U.S. forces in Iraq.35 These forces serve in noncombat roles, predominantly serving as military advisers to the Iraqi security forces and, to a lesser extent, conducting special operations kill and capture raids.

ISIS has also established a 6,000-strong force in Libya. Fighters have come from other North African countries, as well as Iraq and Syria, taking advantage of the years of political turmoil there to acquire territory. The U.S. recently begun conducting airstrikes against ISIS in Libya and the new UN-backed unity government is working to secure the country.

Radicalization and Recruitment

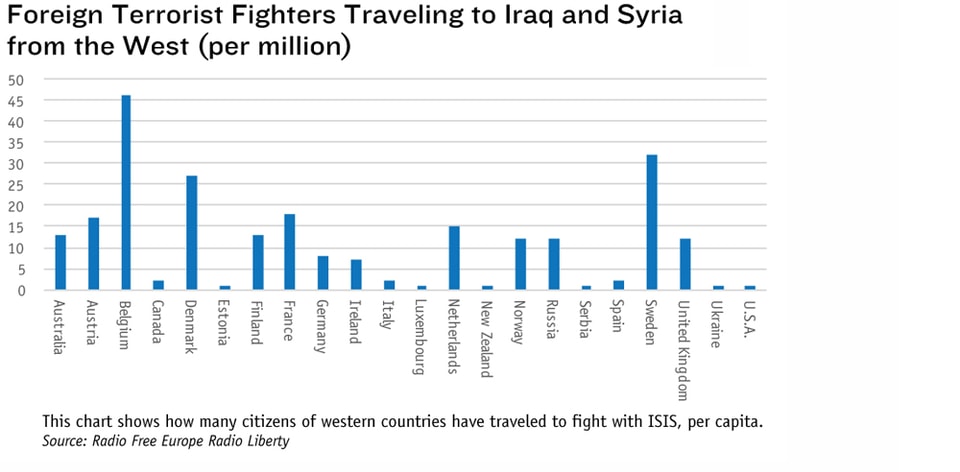

The growth of ISIS is in part a result of their successful recruitment and radicalization efforts. This has increased the number of foreign fighters flocking to Iraq and Syria to join ISIS, some of whom might return to carry out attacks in their homeland. The UN estimates that about 30,000 foreign fighters from over 100 countries have joined ISIS and related groups.36 Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Turkey are the leading nationalities of foreign terrorist fighters. Russia, France, Germany, the UK, and Belgium are the top western countries with nationals becoming foreign fighters. The U.S. is estimated to have had about 250 fighters go to Iraq and Syria to fight with ISIS, and about 40 have returned.37

Al Qaeda carried out a structured, selective, top-down approach to choosing recruits and bringing them to al Qaeda safe havens for training and planning an attack. Once these recruits, most often of Arab descent, were trained, they went out to western targets under al Qaeda instruction. These attackers took direct guidance from al Qaeda leadership in coordinating attacks, which often led to western law enforcement disrupting the attack.38 By contrast, ISIS is not so selective, and therefore recruits far more volunteers than al Qaeda ever did. The porous border between Turkey and Syria allows easy passage for foreign fighters. ISIS’s enhanced use of the internet and social media allows it to reach followers in the West, who can be radicalized and trained into homegrown terrorists without ever traveling to Syria. ISIS followers who carry out attacks have demonstrated a degree of independence unseen in al Qaeda attacks, shielding their plans from counterterrorism officials.

U.S. Efforts to Counter Radicalization and Recruitment

These terrorist groups threaten our allies abroad, but there are two ways terrorists are most likely to attack us on the homeland: (1) sending a terrorist to the U.S. with a western passport and (2) radicalizing people already here. The U.S. has worked to block both paths. Following the Paris attacks, the U.S. changed the Visa Waiver Program to require that any citizen of one of the 38 participating countries who is also a citizen of Syria, Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia, or Yemen, must now apply for a visa before traveling here. Those who have been to any of these countries in the last five years are also now required to apply for a visa. The visa application process will include an interview, fingerprinting, and screening by U.S. officials to determine if they should be allowed to enter the U.S.39

In recent years, the U.S. has stepped up its efforts to address radicalization and counter violent extremism. In 2011, the administration developed a strategy to counter violent extremism. This includes: enhancing federal-local community engagement, expanding law enforcement expertise on countering violent extremism, and countering extremist propaganda.40 The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s new Countering Violent Extremism Task Force is a permanent office that shares best practices to bolster the capacity of international partners to address the problem. The U.S. held a summit in 2015, bringing together world leaders, local leaders, and civil society to better understand the threat, counter extremist narratives, and address how to safeguard communities against the threat.

The U.S. Defense Department’s Cyber Command has intensified their effort to prevent ISIS members from using social media to recruit and influence potential followers. The U.S. State Department recently modified its approach to countering ISIS messaging with the new Global Engagement Center. This will allow the U.S. to work with regional partners and use data-tested messaging strategies to counter terrorist narratives. Some technology companies are also committed to preventing the use of their platforms by ISIS and related terrorist groups for recruitment and radicalization. Twitter has taken down more than 125,000 accounts related to ISIS, and Facebook has agreed to do the same. The U.S. government is working with technology companies to establish the most effective ways to prevent terrorist messaging, discredit ISIS and terrorist propaganda, and prevent recruits from being influenced by terrorist narratives.

Conclusion

The U.S. continues to build the capacity of regional partners to fight back against these groups, while also carrying out special operations attacks and airstrikes. ISIS remains the most enduring threat, seeking to expand their territory and influence across the Middle East. U.S. and coalition efforts have been successful in pushing back its territorial gains, but the war against terrorist groups and radicalization will be a long-term effort. Gains on the battlefield alone will not be enough to defeat the ideology behind ISIS. For information on how U.S. policymakers can craft a tough and smart strategy to defeat ISIS and related groups, see our Plan to Combat Terrorism.