Report Published June 6, 2018 · 10 minute read

The Half and Half Rule: Putting Accreditors on Probation for Failing to Protect Students

Michael Itzkowitz, Wesley Whistle, & Tamara Hiler

When students and families hear that an institution is accredited, they believe it’s a signal from the U.S. Department of Education that the school will provide a quality education for those who choose to enroll.1 But are the accrediting agencies that give institutions their stamp of approval actually guaranteeing institutions are demonstrating quality outcomes for their students?

The federal government relies on the U.S. Department of Education staff and an independent advisory board known as the National Advisory Committee for Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI) to provide recommendations to the Secretary of Education about an accreditor’s ability to assess how well the institutions and programs they accredit serve their students.2 Each body makes a recommendation to a “Senior Designated Official” within the Department who has the final say about whether accreditors should receive federal recognition. Only then do institutions gain access to federal student aid programs, as they must be accredited by one of these federally recognized entities in order to do so. This recommendation process is designed to ensure that accreditors are providing a minimum level of quality assurance for students and taxpayers alike—the latter of whom invests nearly $130 billion dollars a year in grants and loans that flow to institutions of higher education.

And while college continues to benefit most who attend and earn a degree, this process still allows a significant number of low-performing institutions to fly under the radar, receiving the green light from their accreditors year after year even if they continuously show poor outcomes for the students they serve. These institutions enroll millions of students and receive billions of dollars of federal student aid on an annual basis despite their substandard performance.3 And many of these poor-quality institutions are heavily concentrated within a small number of accreditors—begging the question, what can policymakers do to ensure that a few bad accrediting agencies don’t leave millions of students with little chance to graduate, obtain successful workforce outcomes, and pay down their education debt?

The Problem

There are Limited Tools for Measuring Achievement by Accreditor.

Until recently, the federal government gave very little consideration to how institutions within an accreditor’s portfolio were actually serving their students. That’s because the Department of Education is actually prohibited by law from setting any minimum performance thresholds for institutions or the accrediting agencies that oversee them.4

NACIQI, who acts as an accreditor for accreditors, started to take this matter into its own hands in 2015 by asking the Department of Education to provide information on the general performance outcomes for the institutions that each agency accredits through new “accreditation dashboards.” These dashboards would serve as a way to better measure student achievement at institutions across the country by looking at graduation, earnings, and repayment rate data for institutions within each accreditor’s portfolio.5 This pilot project has served as a fruitful starting point to better understand accreditors’ ability to assess and demand quality. However, these dashboards are not written into law—meaning that there is no long-term guarantee that the public or NACIQI will be able to access this information if the Department of Education chooses to let these dashboards lapse.

Accreditation Isn’t a Proxy for Quality.

In addition, while accrediting agencies are obligated by law to look at student achievement, the way they assess and approve “appropriate measures of success” at the institution level doesn’t necessarily translate into successful long-term outcomes for the students those institutions serve.6 For example, there are currently 998 accredited institutions where fewer than 50% of their students ever earn a degree.7 There are also 1,818 institutions where less than half of students are able to earn more than an average high school graduate ($25,000), even six years after entering college. And an astounding 2,447 institutions have fewer than 50% of their loan-holding students who are able to pay down at least $1 on their loan principal within three years of leaving the institution and entering repayment.8 While some accreditors oversee institutions that perform well on all three of these key metrics, the reality is that several accrediting agencies continue to oversee numerous institutions within their portfolios that leave the majority of their students degreeless, underemployed, and unable to pay down their student loans after attending.

Accreditors Rarely Revoke Accreditation Status.

All accreditation agencies are membership organizations, meaning their institutions pay annual dues to maintain accreditation status. Therefore, terminating the accreditation of an institution also means a loss of revenue for the agency itself, creating a perverse incentive to keep low-performing institutions accredited, even when they fail to serve their students. From 2014 to April 2017, only 36 out of the more than 5,000 institutions (less than 1%) nationwide had their accreditation status revoked.9 Even if some institutions are shown to be consistent low-performers, this membership structure may encourage some accreditors to continue giving their stamp of approval, as doing differently would ultimately affect their bottom line.

No One is Watching the Watchdog.

Right now, there is no federal requirement for accrediting agencies to demand successful outcomes from the institutions they review. While accreditation dashboards have provided a starting point to increase transparency, they currently serve a very limited role in holding accreditors accountable for their institutions’ outcomes. NACIQI has just begun to use these dashboards as part of their recommendation process; however, Department of Education staff does not use student outcomes when advising the Secretary of Education on recognition of accreditors. Instead, the Department mainly uses a compliance checklist to make their recommendation on whether or not an agency should maintain its status as a federally recognized accreditor. In other words, student outcomes currently carry very little weight in determining which accreditors are equipped to be true arbiters of quality at institutions of higher education.

The Solution

To better ensure that accrediting agencies only give their stamp of approval to institutions that are serving students well, we should apply a “half & half” rule, requiring that at least half of an accreditor’s institutions show positive outcomes for at least half of its students. If an accrediting agency shows that a majority of its member institutions leave more than 50% of its students unable to graduate (as measured by the federal Outcomes Measures graduation rate which includes part-time and transfer students), unable to earn more than an average high school graduate, and unable to begin paying down their student debt within a reasonable time period, that agency should be at risk of losing its federal recognition to accredit institutions.10

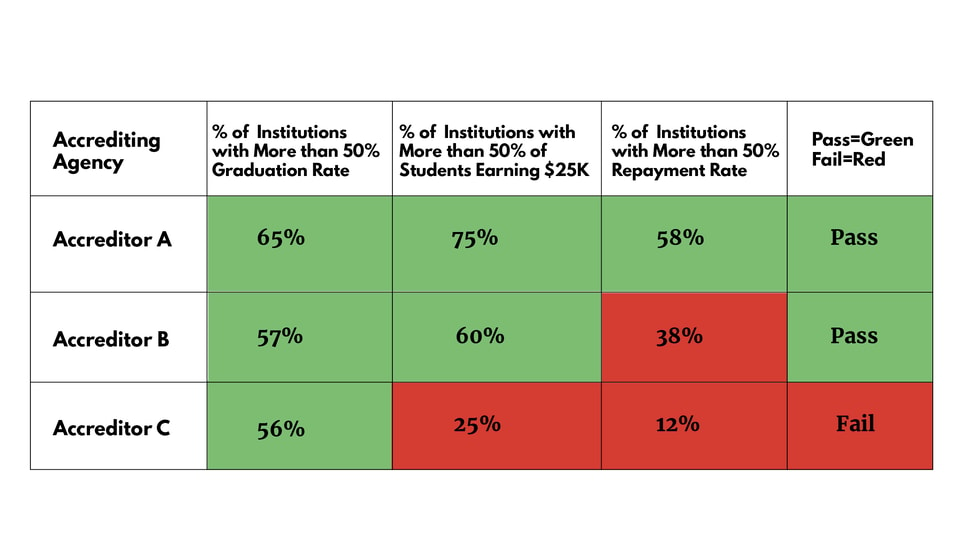

To assess whether an accreditor should lose this recognition, Congress should require accrediting agencies to have over half of their member institutions perform above 50% on at least two of the three performance thresholds listed above. For example, if an accrediting agency showed that less than half of its member institutions were able to perform above the 50% threshold within any given performance category, that accreditor would be recognized as “failing” that individual metric. If more than half of the accreditor’s institutions fail two out of three performance metrics within a given year, the accreditor risks losing federal recognition altogether. As you can see in the hypothetical example below, “Accreditor C” would be the only accreditor to receive an overall “failing” rating since less than half of its member institutions were able to meet the 50% thresholds for the earnings and repayment metrics.

Accreditor “Probation”

Accrediting agencies that fail at least two of the three performance measures should be put on a “probation” period with NACIQI and the Department of Education. During this time period, they should be required to undertake plans for improving institutional performance over the next five years. This could include either improving performance outcomes at the institutions they currently accredit or terminating accreditation from institutions that are consistently low performers that are bringing down their overall stats. And to help minimize the incentive to keep low-quality institutions accredited because of reliance on the dues paid to their accreditor, the Department could fill that gap and subsidize the cost to an agency for revoking an institution’s accreditation.

If after five years, most institutions within an agency’s portfolio still fail two of the three performance thresholds, their ability to operate as a federally recognized accreditor—a gatekeeper for access to federal aid dollars—should be terminated. This would better ensure that the watchdogs who are supposed to be in charge of overseeing higher education quality in the United States are also held accountable, as they have historically been given a free pass on the long-term student outcomes of the institutions they oversee.

Critiques and Responses

These metrics could unfairly target colleges that serve a higher share of non-traditional and low-income students.

These metrics help ensure that most students who attend any accredited college have a better than 50% chance of graduating, obtaining a good job, and paying down any educational debt that they may incur. It’s reasonable that—regardless of institutional mission—most institutions within an accrediting agency’s portfolio should provide a majority of their students with an opportunity to perform above these minimum thresholds of success. Additionally, unlike the statutory graduation rate that treats all “transfer-outs” as non-graduates, the metric used to determine a school’s graduation rate in this instance could remove students who transfer out altogether, rather than counting that as a negative outcome. This would help avoid unfairly penalizing community colleges that have a higher transfer student population.

These measures assess different student outcomes at different points in time.

The three student outcomes suggested here help identify a consistent pattern of systemic failure. The Outcome Measures graduation rate measures the percent of students who have obtained an award or degree eight years after entering an institution, while the percentage of students earning above the average high school graduate captures loan-holding students’ earnings six years after entering an institution, and repayment rate measures the percent of students who have paid down at least $1 on the principal of their federal loans three years after they entered repayment. While these measures may capture different cohorts of students at different times, they serve as the best student outcome information that is currently available at the federal level. An accrediting agency would only risk losing its federal recognition if over half of their member institutions failed at least two out of these three metrics. That means accreditors could work with institutions to put in place improvement plans that addressed one metric at a time to improve their standing and avoid this fate.

Earnings differ by major and by region.

To mitigate the concern that it would be unfair to evaluate earnings data for accrediting agencies with institutions in different regions of the country and different specializations, we suggest not looking at median earnings, but rather the percentage of students earning above the average high school graduate ($25,000), which serves as one way to evaluate the financial gain of attending an institution of higher education in the first place. Teachers and engineers alike should both be able to earn at least $25,000 if their programs have adequately prepared them to enter and succeed in the workforce. This also addresses differences in earning by region, allowing “success” to only be defined by a college’s ability to provide value to a student beyond what they would be likely to make if they had never attended a postsecondary program at all.

Conclusion

As the main arbiters of quality and gatekeepers of federal funds flowing to institutions, the government must have some minimum standards in place to ensure that accrediting agencies only provide their stamp of approval to institutions that provide their students with more opportunities after attending. And while some accrediting agencies show exemplary outcomes, others continue to accredit low-performing institutions year after year with little to no repercussions for doing so. The “signal” of federal accreditation needs to mean more than it does today by better protecting students who rely on it and the taxpayers who fund their educational endeavors. This policy helps accomplish that by requiring better outcomes for the watchdogs in charge of overseeing our institutions of higher education.