Report Published May 14, 2014 · Updated May 14, 2014 · 19 minute read

Americaña: Bipartisan Misinterpretation of “Hispanic America”

Michelle Diggles, Ph.D.

Many in the Republican Party characterize Hispanics as a monolith of poor, illegal immigrants refusing to learn English and assimilate by embracing American values. A strain within the Democratic Party assumes that Hispanics are born into their Party and care exclusively about immigration reform. Reductionism and stereotyping by both sides obscures key facets of American Hispanics’ experiences and values, and treats a diverse and growing segment of our population as if it were homogenous. In this report, we debunk common misperceptions on both sides and offer a more nuanced view of Hispanic voters in America.*

Special thanks to Chiqui Cartagena, whose book Latino Boom II: Catching the Biggest Wave Since the Baby Boom inspired the title of this report.

Introduction

Since 2000, America’s Hispanic population has increased by 50% to 53 million.1 Hispanics now compose 17% of the U.S. population and are expected to increase to nearly three in ten by 2050.2 Hispanic political power is also growing, as their share of the national electorate has grown by one point in every presidential election since 2000. They comprise 38% of the most populous—and vote rich—states of California and Texas, not to mention nearly half of New Mexico and more than 20% of the swing states of Arizona, Colorado, Florida, and Nevada. Despite their size and potential for political impact, both parties tend to caricature Hispanics. In this report we offer an alternative perspective to the stereotypes and misperceptions dominating the beltway.

But first: The label “Hispanic” itself is problematic and not completely embraced by those considered members. The term was put into widespread use after the 1970 U.S. census when the label was adopted as a formal category.3 Americans commonly defined as “Hispanic” or “Latino” are considered part of a common ethno-linguistic group. That is, membership is predicated on the group’s real or perceived shared characteristics of ethnicity (sense of common descent or relatedness) and language (assumed to be Spanish-speaking). However, Hispanics are more likely to label themselves based on their family’s country of origin (54%) or call themselves simply Americans (23%).4 Only 20% primarily refer to themselves as “Hispanic” or “Latino.”5 However, we will use “Hispanic” throughout this report because it is the dominant description used in politics today.

Listen up, Republicans

Hispanics are not all undocumented.

Republican stereotypes of Hispanics can be boiled down to one word: ”illegal.” In 2012, Mitt Romney endorsed “self-deportation” (making the environment so harsh for undocumented immigrants that they would voluntarily return home) and spoke primarily of fixing immigration when addressing the Hispanic community.6 Back in 2010, then Senate candidate Sharon Angle ran an ad featuring people literally sneaking under a fence over the border while the narrator accused Senator Harry Reid (D–NV) of opposing Arizona’s immigration law.7 The otherizing of all Hispanic-looking people (e.g., “show me your papers” laws) has driven a wedge between Republicans and the Hispanic community more broadly.8 Even 42% of Hispanics who self-identify as Republican say their party is ignoring or being openly hostile to Hispanic voters.9

After the 2012 presidential election, several prominent conservative commentators (e.g., Sean Hannity) embraced comprehensive immigration reform, believing it was crucial to Republicans’ electoral success. In their autopsy of the 2012 election, the Republican National Committee authors noted, “If Hispanic Americans hear that the GOP doesn’t want them in the United States, they won’t pay attention to our next sentence.”10 Their top recommendation to improve Republican standing with the community was a policy focus on immigration reform. Yet this diagnosis may have missed the mark. Hispanic voters may be less concerned with Republican positions on immigration reform and more concerned that Republicans think of all Hispanics as “illegals” and not fully American.

Republicans tend to stereotype Hispanics as primarily undocumented immigrants. Yet 64% of Hispanics in the U.S. are native born—making them legal U.S. citizens by birthright. Of the remaining 36%, 11% are foreign-born citizens and 8% are legal non-citizens.11 Pew estimates that of the 11.7 million undocumented immigrants, 77%—or approximately 9 million—are from Mexico and Latin America. Thus, about 17% of Hispanics are undocumented immigrants. And the number of undocumented immigrants arriving and residing in the U.S. has fallen sharply in recent years. Apprehensions of Mexican immigrants at the border fell to fewer than 300,000 in 2012—down from the peak of 1.6 million in 2000—due to a combination of bulking up of border security and the economic recession.12

Despite the low levels of undocumented immigrants among the Hispanic community, the anti-Hispanic rhetoric unleashed by Republicans when they speak of immigration impacts the community writ large. Further, many Hispanics born in the U.S. care deeply about immigration reform, regardless of their citizenship. And assumptions surrounding citizenship and rhetorical demonization of an entire community may have had the unintended effect of unifying the diverse Hispanic population, at least temporarily. That’s what happened in 2006, when the passage of The Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005 (H.R. 4437) triggered unprecedented political organization within the Hispanic community.

This House-passed bill increased penalties on both undocumented immigrants and anyone assisting them. This political threat was turned into an opportunity that, according to academic accounts, “activated multiple Latino constituencies, including the Latino citizenry and organizational elite, to come together in solidaridad, or group solidarity, for immigrant rights.”13 Through the Catholic Church, Spanish-language media, and local schools, the community organized rallies and marches throughout the country, with 3.5–5 million Hispanics participating in the actions.14 In the end, the House bill never became law due to key differences with the Senate version, notably a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

Prior to this period, attitudes on immigration were divided within the Hispanic community. Polls taken in 2004 indicated a gulf between first and second generation Hispanics on the one hand and third generation Hispanics on the other. Specifically, third generation Hispanics were less likely to want to increase legal immigration from Latin America and more likely to say illegal immigration hurts the economy than more recent immigrants.15 This is not surprising. Historic patterns suggest that as immigrants structurally integrate into American society and assimilate to the dominant cultural values, they will support more restrictionist immigration policy.

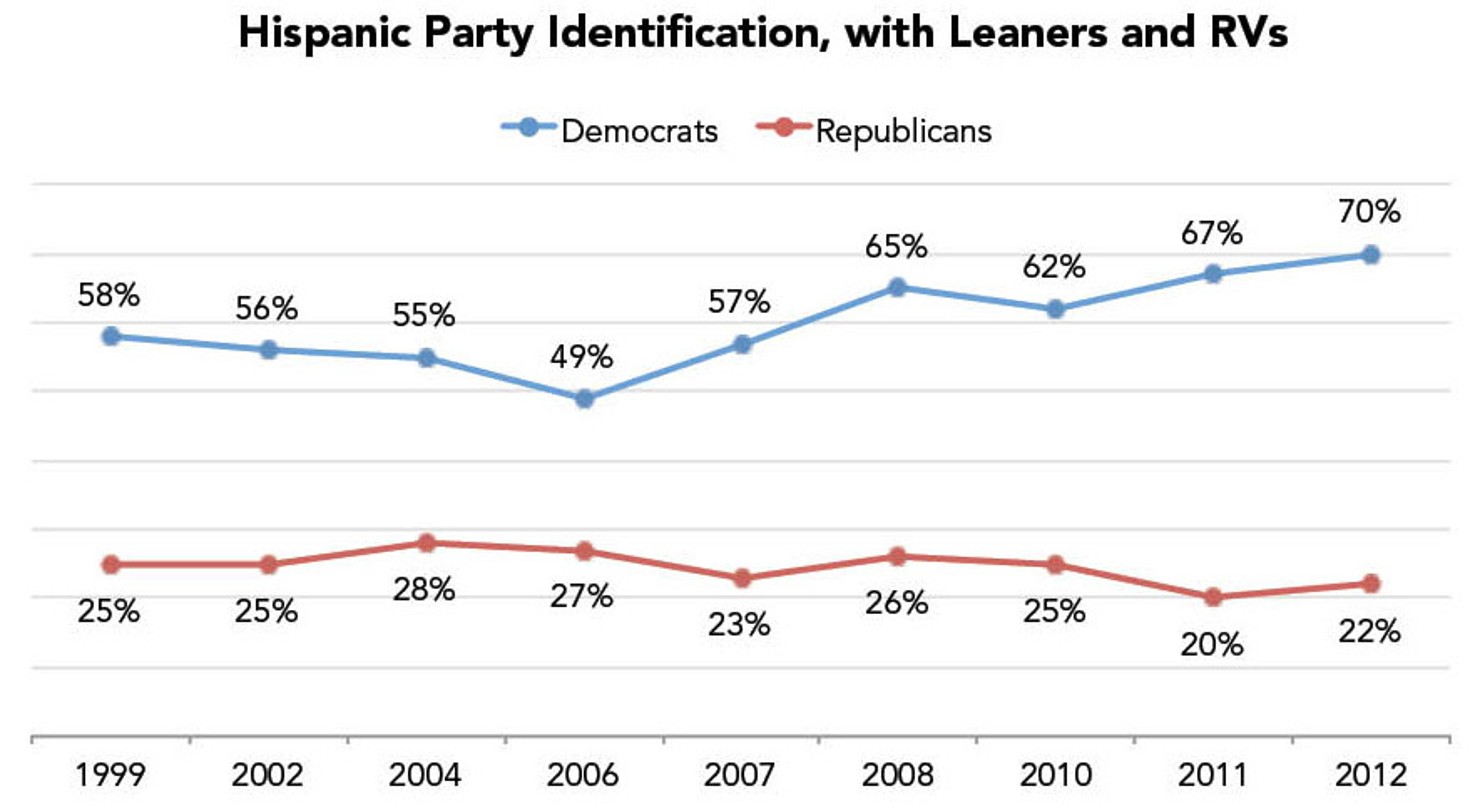

But by 2006, as the table above demonstrates, the generational dichotomy on immigration was beginning to collapse. Further, there was broad agreement that the immigration marches signaled the start of a long-term social movement (64.1% for first and second generation and 64.2% for third generation) and a shared belief that the movement would result in higher voter turnout come November (77% for first and second generation and 75.1% for third generation).16 And when looking at trends in party identification, 2006 does appear to be a turning point. Hispanics have tended to identify as Democrats more than Republicans, or lean in that direction. But after 2006, that gulf widened. In Pew’s analysis of Hispanic party identification, which includes leaners—Independents who say they lean towards one party or the other—the Democratic margin rose from a low of D+22 in 2006 to D+34 in 2007, D+39 in 2008, and D+48 in 2012.17

Source: Pew

These data points suggest that the immigration debate had the effect of bridging the gulfs within the Hispanic community. In many ways, it may have turned what was once merely a label ascribed by outsiders onto people who claimed no common group identification into a self-described and unifying political identity. As positions on immigration issues aligned within the community, the marches themselves functioned as collective vehicles for building a social movement around immigration. Hispanics felt this coalition would be durable—the opening act, not the climax—and would translate into political power. As the party identification data indicates, the 2006 immigration marches and legislative battles altered what had been a relatively stable trend of partisan identification by Hispanics. Taken together, the construction of cultural commonality, the perception of unfairness by political actors (Republicans in the wake of the H.R. 4437), and the belief in their own political efficacy demonstrates how political mobilization was intertwined with and created ethnic solidarity or group consciousness among a previously diffuse population.18*

Group consciousness is defined as instances when a group maintains a sense of affinity and group identification with other members of the group, which leads to a collective orientation to become more politically active,” Sanchez, p. 428. “Ethnic solidarity is rooted in social conditions that trigger heightened ethnic awareness across other identities.…Solidarity is not predictive of lifelong behavior,” Barreto, Manzano, Ramírez, and Rim, p. 738. Determining which of these best captures the Hispanic experience and resulting political orientation is crucial to understanding the stability and durability of Hispanic partisan identity in the future.

Hispanics are not the 47%.

When Mitt Romney said President Obama was “giving a lot of stuff to groups” and talked about the 47% who supposedly received handouts from the government, he specifically mentioned the Hispanic community.19 Romney’s gaffe symbolizes stereotypical images of Hispanics as poor and unwilling to help themselves. For example, non-Hispanic whites say “welfare recipient” (51%) and “less educated” (50 percent) describe Hispanics very or somewhat well.20 But these views miss the mark. Rather, Hispanics are strivers, as evidenced by their entrepreneurial spirit. Indeed, between 1990 and 2012, Hispanic self-employment—a key measure of entrepreneurialism— increased 17 times faster than the rate among non-Hispanics.21

There are three problems with this view that Hispanics are poor. First, it masks considerable variation within the community. While 13% of Hispanics age 25 and older have a bachelor’s degree or more, that ranges from 7% for Guatemalans and Hondurans to 51% among Venezuelans.22 While the median income for Hispanics is $39,000, that figure varies from $31,000 for Hondurans to $55,000 for Argentinians.23 Poverty rates, health insurance, and home ownership levels all vary considerably—and reflect the diversity of the Hispanic population.

Second, diversity in countries of origin and the timing of migration have resulted in different experiences and impacted legal and socioeconomic status. Salvadorans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans tended to come to the U.S. at different time periods and for different reasons. Salvadorans fleeing their war-torn country in the 1980s were given legal status. In turn, they could seek different types of work—typically higher paying—than an undocumented immigrant.24 Puerto Rico is an American protectorate; thus, Puerto Ricans are counted as American citizens—with all of the rights and benefits included. And Cubans have the lowest poverty rates of any Hispanic group and are more likely to own their own home—likely due to special status of Cuban émigrés.25

Finally, it is wrong to imply that Hispanics are unwilling to work to change their circumstances when all the evidence points to the opposite. Among recent Hispanic immigrants, 55% say economic opportunity is their primary reason for coming to the U.S. The second most cited is family reasons (24%), followed by educational opportunities (9%).26 These numbers are unsurprising, as Hispanics have surpassed whites in college enrollment among recent high school graduates (49% to 47%).27 Further, 87% of recent Hispanic immigrants believe the opportunity to succeed is better in the U.S. than their country of origin.28 And 75% believe most people can get ahead with hard work, a sentiment shared by only 58% of all Americans.29 These numbers paint a clear picture of eager Hispanic immigrants coming to the U.S. for an opportunity to work hard and achieve, provide a better life for their family, and invest in their kids’ futures—not to beg for a handout as many Republican politicians imply.

Hispanics are assimilating.

Much of the Republican opposition to comprehensive immigration reform has stemmed from concerns about rewarding law-breakers. But they also express fears that Hispanics are not assimilating into American culture.30 Every year in America there are a series of parades and events where flags from foreign countries are proudly displayed. Indeed, St. Patrick’s Day—replete with Irish flags, parades, and corned beef and cabbage specials—is virtually a national American holiday. These celebrations of diverse heritages fail to illicit concerns from Republicans. But expressions of pride among Hispanics for their heritage, such as the raising of a Mexican flag, cause many Republicans to accuse Hispanics of subversive behavior.

These Republican concerns are misguided in their interpretation of cultural assimilation, values, and intragroup connectivity. First, culture is additive, not reductive. Language serves as a proxy for this issue, whereby a belief that speaking Spanish signifies an unwillingness to become fully “American.” Opposition to bilingual government publications and support for English-only laws are symptomatic of this fear. In a 2012 study, 44% of non-Hispanic whites said “refuse to learn English” describes Hispanics very or somewhat well.31 This singles Hispanics out as different from what is considered the typical citizen.

But Hispanics don’t choose to be Mexican or American, or to speak English or Spanish. Instead, they often fuse Hispanic and American culture. As one Hispanic scholar noted:

I am 100 percent American and 100 percent Latino, so when you ask me to choose between the two, you are not going to get an accurate answer.#

We see evidence of this in surveys about language use. Half of Hispanics consume news media in both English and Spanish. Another 32% consume news in English only with 18% in Spanish only—although these figures are lower on Spanish language viewing than others (e.g., Nielsen).32 Spanish is often spoken at home to maintain ethnic identity, which is linked to the consistent influx of new Hispanic immigrants.33 Nielsen found that 59% of Hispanics are bilingual with 25% speaking Spanish only and 16% English only. But maintaining a cultural connection through sometimes speaking Spanish has not displaced being an American or using English. While 87% of Hispanics believe English is the language of success in the U.S., 95% also think it is important for future generations to learn Spanish.34

Second, Hispanics have embraced traditional American values. As noted above, Hispanics, more so than Americans overall, believe that hard work pays off in America. Their top priorities reflect issues that resonate with most Americans. While immigration played a central role in the construction of a recent national Hispanic political movement, it has not been the dominant priority of this community. Since 2008 (at least), Hispanic voters have cited jobs and the economy, education, and healthcare as their top three most important priorities.35 Hispanic adoption of American values is nowhere more evident than in naming undocumented youths DREAMers—a clear reference to their goal of achieving the American Dream.

Finally, outside the political context noted above, Hispanics themselves see little similarity with each other. Language, Catholicism, and a 500 year history in the Americas provide common reference points. While differences persist, similarities may outweigh them. In a recent survey, 69% of Hispanics said they do not share a common culture with one another, compared to only 29% who believe they do.36 Diversity within the Hispanic community may undermine any sense of a common, pan-ethnic identity as a kind of cultural rival to Americanness. But constant reinforcement of relatedness—by politicians, the media, even business leaders—creates a shared identity and cultural position.

Don’t Assume, Democrats

Hispanic views of immigration are complicated.

Democrats have tended to emphasize immigration as a top issue for the Hispanic community. And immigration has helped Democrats garner support from Hispanics. Partially this is because Republicans have locked themselves out of the conversation—giving Democrats an opening. But Hispanic views of immigration reform are complex. On the one hand, it does not regularly rank high on the list of priorities within the community, and it certainly should not be seen as the single defining issue for Hispanic voters. For example, in a 2012 survey of political priorities, 55% of Hispanics said education was extremely important, followed by 54% for jobs and the economy, and 50% for healthcare. Immigration came in fifth, at 34%.37 Jobs and the economy, health care, and education tend to be the top three Hispanics priorities annually in surveys. And when presented last fall with five domestic priorities, immigration ranked last, behind even the deficit.38

However, many Hispanics likely consider immigration to be an issue that is unique to their community. They may believe that if they do not hold that issue deeply, no one else will (although many Americans farmers and business leaders also hold this issue deeply as it affects their livelihood). Further, media portrayals reinforce the connection between Hispanics and immigration. Thus, immigration may not be the most important political issue in surveys of top concerns among Hispanics, but their passion on immigration may be strong.

Within the immigration reform conversation, Democrats may be emphasizing policies that do not reflect the most immediate concerns of the Hispanic community. For example, 55% of Hispanics say that it is more important for undocumented immigrants to be able to live and work in the U.S. without the threat of deportation. By contrast, only 35% emphasize a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.39 And the failure to pass immigration reform may not be the boon Democrats assume. While 43% of Hispanics would blame Republicans for the failure to pass legislation, 34% would also blame Democrats or the President.40

Finally, some Hispanics, along with other immigrant groups, worry about granting legal status to undocumented immigrants. A sizeable minority say it would lead to more people coming to the U.S. illegally (43%) and would reward illegal behavior (41%).41 And on the legislation passed by the Senate in 2013, 67% say they don’t know enough about the details to determine whether or not to support the bill.42 Still, 69% of Hispanics say that it is important that new immigration legislation is passed.43 But it is clear their political priorities extend well past that single issue.

Hispanics are not born liberal Democrats.

In 2012, President Obama won the Hispanic vote by 44 points. But that same year, 50% of Hispanics identified as Independents and 32% as Democrats.44 Despite winning their votes in recent presidential elections, Democrats must be vigilant. Weak partisans and Democratic-leaning Independents are prone to party- and vote-switching over successive elections.45 And Hispanics express lukewarm feelings about the Democratic Party. Only 27% think the Democratic Party cares a lot about the issues and concerns of Hispanics.46 This and their lack of identification as self-described Democrats suggests that Hispanic attachment to the Democratic Party is shallow rather than deep.

Hispanics are also more likely to identify as a moderate than either a conservative or a liberal. In a 2013 Public Religion Research Institute survey of Hispanics, 45% identified as politically moderate, 27% as conservative, and 23% as liberal. The general population, the same study noted, is 36% moderate, 36% conservative, and 23% liberal.47 Consistent with their plurality moderate label, while Hispanics have tended to support a more activist government in surveys, they also express skepticism about government programs. For example, in a March 2014 survey, Hispanics were divided 47%-47% on support for the Affordable Care Act, a stunning turnaround from September 2013 when 61% favored the law.48 And their approval of the ACA has tracked with presidential approval, down from 63% last fall to 48% in March 2014.49

Religion is a potential flashpoint for divergence between Hispanics and liberal Democrats. Traditional perspectives on religion dominate in much of the Hispanic community. For example, 61% believe the Bible is the literal word of God, and only 5% do not believe in God.50 The importance of religion and the link between religion and morality among Hispanics partially explains their views on issues like abortion, which 52% say should be illegal in all or most cases.51 On the question of morality, 48% say their moral evaluation of having an abortion depends on the circumstances.52

As religious identity among Hispanics change, we could see more tensions between the values and beliefs of Hispanics and liberal Democrats. Overwhelmingly, Hispanics are Catholic (62%), with only 19% identifying as Protestant, and 13% as Evangelical. Among the U.S. public generally, Catholics represent 23% of the population, Protestants 50%, and (white) Evangelicals 18%. But we see greater identification with Protestantism among U.S.-born and third generation or later Hispanics. While 69% of foreign-born U.S. Hispanics identify as Catholic, only 51% of native-(U.S.) born and 40% of third generation or later Hispanics call themselves Catholic. There is a reverse trend with Protestants, where only 16% of foreign-born and 22% of native-born Hispanics identify as Protestant, but 30% of third generation and later do so.53

This shift toward the national mean is also evident in the Hispanic community’s views of the government. Hispanics overwhelmingly support a bigger government providing more services (75%) compared to a smaller government providing fewer services (19%), a value usually associated with Democrats. Many Hispanics likely expect more government services because they come from countries where government services are extensive. The U.S. population generally is more evenly divided, with 41% supporting a bigger government with more services and 48% a smaller government with fewer services in recent surveys. But once again, we see differences within the Hispanic community based on time in the U.S. While 81% of recent immigrants and 72% of second generation Hispanics support a bigger government with more services, only 58% of third generation and later agree.54 This divergence is yet another illustration point for why the Democratic Party cannot simply assume that Hispanic voters will automatically be theirs for years to come.

Conclusion

While the Hispanic population has soared over the past two decades, their impact on politics has been understated until recently. The Democratic Party has been more successful in attracting Hispanic support over the past few elections but has also benefited from a lack of real alternative due to nativist language and narrow view of prominent Republicans on “Hispanic issues.” Yet there are rising Hispanic stars in the Republican Party, such as Governors Susana Martinez (R-NM) and Brian Sandoval (R-NV) as well as Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Marco Rubio (R-FL), and with their help their party is trying to find ways to embrace the community.

Democrats cannot be complacent and should work to deepen their connections with the Hispanic community beyond immigration. Hispanics are strivers—entrepreneurs and small business owners. And Democrats have not been able to attract as much support from small business owners as the rest of the population.55 While Mitt Romney’s performance among Hispanics was the worst of any Republican presidential nominee for which we have records, it wasn’t that long ago that Republicans attracted sizeable portions of their votes. Former President George W. Bush is credited with saying, “Family values don’t stop at the Rio Grande ... and a hungry mother is going to try to feed her child.”56 In 2004, he won 44% of the Hispanic vote—and reelection. If Republicans abandon their stereotypes or Democrats don’t do the necessary work to keep Hispanic voters in their column, we could easily see this community returning to the ranks of swing voters.