Report Published March 24, 2015 · Updated March 24, 2015 · 7 minute read

Afghanistan: Understanding the Post-Karzai Partnership

Chrissy Bishai & Mieke Eoyang

Takeaways

Afghanistan is at a transition point as our military winds down its combat mission and the new post-Karzai government solidifies its control. The U.S. goal should be to help the Afghans take over security for their country to prevent terrorist safe havens from forming there.

- As our military leaves Afghanistan, total disengagement would repeat our past mistakes.

- Afghanistan’s new unity government appears to be pragmatic and effective, and a better partner for the U.S.

- Securing Afghanistan is complicated, so the President needs flexibility in determining how to address Afghan requests for continued assistance.

Overview

Afghanistan has had a tumultuous modern history. In the mid-1990s, Taliban warlords took power after a messy Afghan civil war, bringing repressive rule and a safe haven for Al Qaeda. After 9/11, the U.S. drove out Al Qaeda and the Taliban government. But beginning in late 2002, the U.S. diverted its attention and resources to Iraq, letting the security situation in Afghanistan atrophy. In 2004, with the election of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, soaring corruption, narcotics trafficking and a violent Taliban insurgency, maintaining the U.S.-Afghanistan partnership became increasingly difficult.1

In 2009, President Obama sent a “surge” of 33,000 American troops to suppress the raging Taliban insurgency and stabilize Afghanistan. Taliban attacks nevertheless increased during the surge years.2

In 2014, at the end of President Karzai’s tenure, the U.S. helped mediate a power-sharing deal in a national unity government between the top candidates, now-President Ashraf Ghani and Abdallah Abdullah, the now-Chief Executive Officer.3 After years of struggle with an increasingly difficult Karzai, Ghani, a technocrat with an American doctorate and decades of experience as an academic and World Bank staffer, appears to be a more promising partner for the U.S. and the other regional players that will have to be part of a negotiated settlement. He signed a bilateral Status of Forces Agreement with the U.S. on September 30, 2014, one day after being inaugurated.4

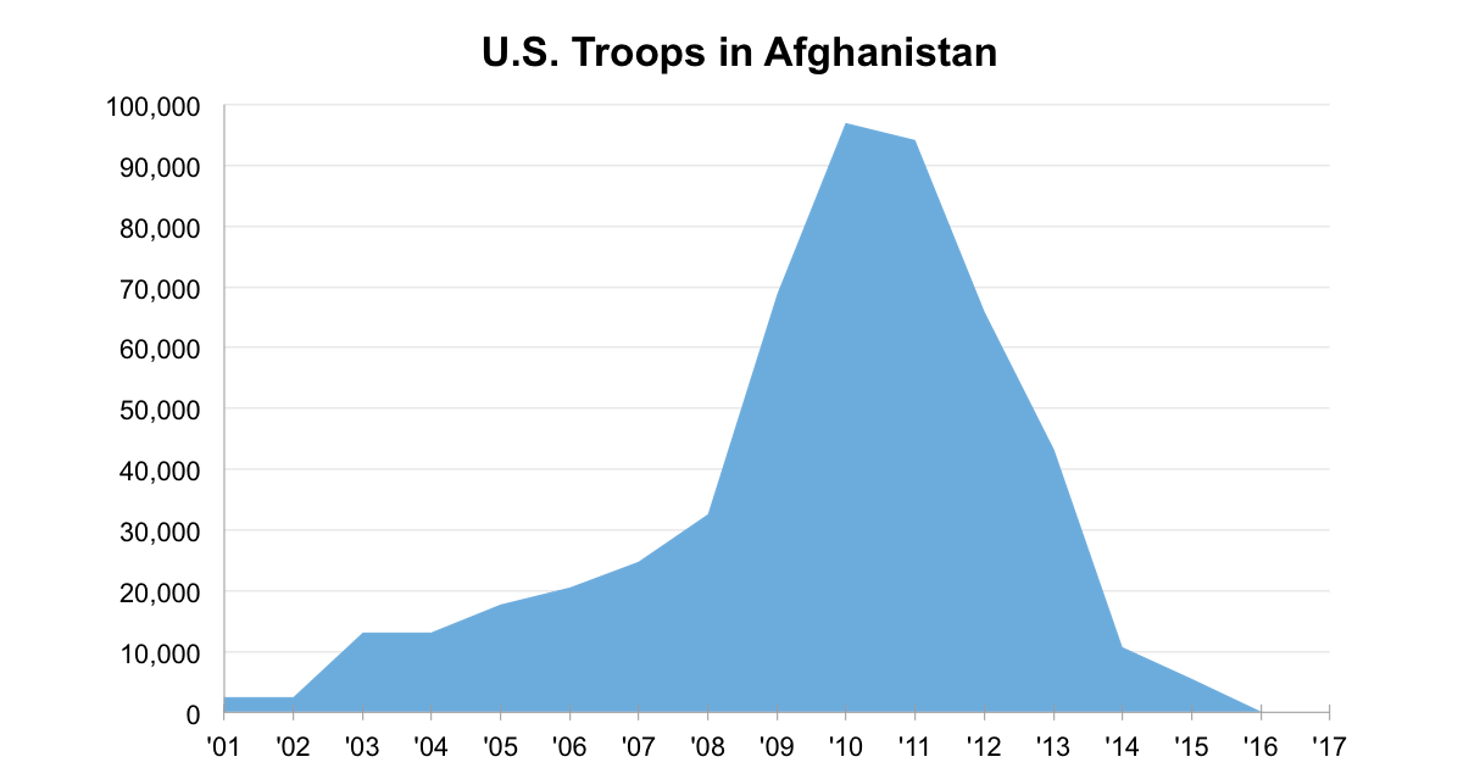

On January 1, 2015, NATO ground forces (International Security Assistance Force or ISAF) officially ended their combat mission in Afghanistan, replacing it with a train-and-advise mission known as Operation Resolute Support (ORS). ORS has 13,000 NATO troops, of which 10,800 are Americans. The U.S. force is currently scheduled to drop from 10,800 to 5,500 by the end of 2015, and to near zero by the end of 2016.5 President Obama has promised that even a small U.S. troop presence will end by 2017.

Source: Congressional Research Service.6 Note: Troop-level data is from December of each year listed; 2015, 2016, 2017 are projections.

Critics of President Obama’s current drawdown schedule say that it puts insurgents on notice, allowing them to “wait out” U.S. withdrawal before reasserting themselves militarily.7 But America cannot be the guarantor of Afghanistan’s security forever. And, after more than a dozen years, Afghans must step up to take on their own security challenges.

Still, past experience suggests that America must continue to help Afghanistan provide for its own security.

An end to our combat mission should not mean that we turn our backs on Afghanistan. We should continue to help them improve their own security forces and governance capabilities. Complete disengagement could risk a return of chaos and give rise to terrorist safe havens.

Late 1980s: After the Soviets ended their decade-long occupation in Afghanistan, the U.S. stopped arming mujahideen insurgents and turned away as the country fell into civil war.

2003-2009: We focused more on the Iraq war effort than responsibly overseeing Afghanistan’s war.

Post-2011 Iraq: Iraq and Afghanistan are very different contexts, but the Iraqi unraveling after U.S. withdrawal provides a cautionary tale. Iraq’s lack of political accountability, massive corruption, and ineffective national military are components that could easily undermine a post-war Afghanistan.

International disengagement may produce another Afghan civil war or a regional proxy war. This is why the U.S. must continue to carefully monitor the geopolitical situation in and around Afghanistan. Also, Afghans must understand that our military transition doesn’t mean disengagement, and that there are non-military supports we can continue to provide them. Congress should seriously consider the recommendations made by the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR)—particularly related to financial oversight and anti-corruption efforts.8 Congress can also offer incentives where possible to help bolster the Afghan army and curb the chances of troop recidivism.

Despite considerable challenges, Afghanistan’s new government appears to be a more pragmatic, cooperative partner for the U.S., and key regional actors, than Karzai's.

As many analysts have warned, Afghanistan faces a huge fiscal gap,9 relying on foreign aid for at least 50 percent of its gross national income.10 President Ghani understands this, emphasizing in his 2014 (and also 2009) presidential bids the importance of government economic investment and the related conditions needed to achieve it: transparency, accountability, strong infrastructure, and a merit-based political system.

Ghani is a well-respected academic and development expert who studied and lived in the U.S. for two decades.11 His deep familiarity with international organizations and long-time experience as a technocrat should provide a firm basis on which to understand Afghanistan’s considerable economic and governance challenges. He’s also showing that he understands the pragmatic approach necessary to oversee meaningful Afghan governance reform.

Both Ghani and Abdallah agree that they must confront the rampant patronage and corruption endemic in Afghanistan’s government. Within Ghani’s first 100 days in office, he visited the western region of Herat to investigate corruption complaints, firing two dozen high-level, well-connected bureaucrats and police chiefs on the spot, and announced that they will be prosecuted.12 He did this to send the message that he’s serious about cutting out the corrupt leaders that Afghans are used to.

Ghani has also been much more receptive than Karzai to work with neighboring Pakistan, a country that remains vital to any regional peace process.13 Negotiations between the Afghan Taliban and Karzai failed in 2013, and he was always mistrustful of Pakistan’s motives in Afghanistan.14 Ghani, on the other hand, has sought to bridge gaps with Pakistan since taking office. The less hostile approach appears to be paying off, as Pakistani officials signaled in February 2015 that Afghan Taliban leaders are finally ready to meet Afghanistan’s (new) central government at the negotiating table.15

The White House is rightly committed to drawing down, but it needs some flexibility to adapt to the security situation in Afghanistan and consider President Ghani’s personal requests for additional support.

After 15 years fighting in Afghanistan, U.S. commanders agree that the war won’t end on the battlefield but in some sort of peace deal at the negotiating table.16 President Ghani understands this but has requested "some flexibility in the [U.S.] troop drawdown timeline."17

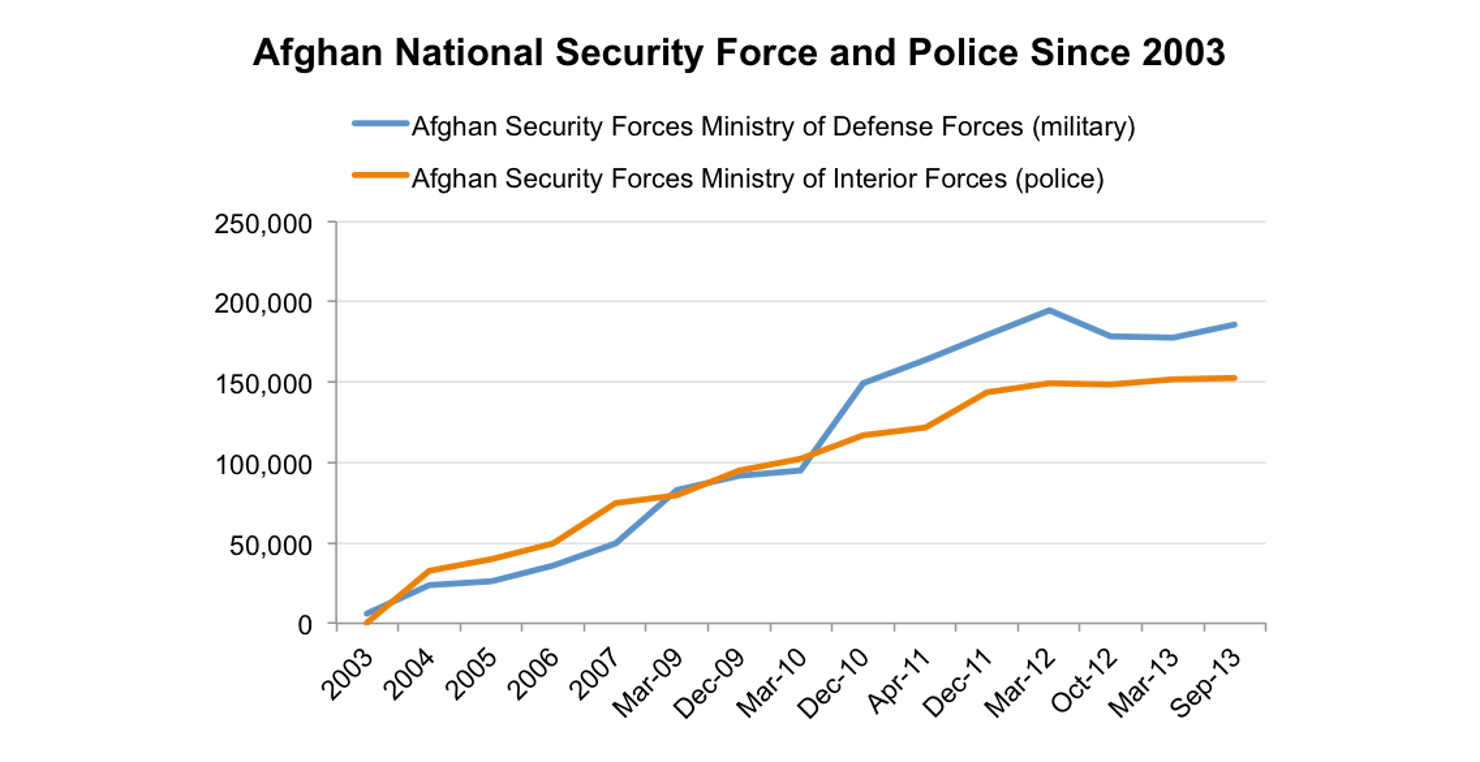

Source: Brookings Afghanistan Index, 201418

Afghanistan’s National Security Force (ANSF) and Police have grown considerably over the last decade. But after massive U.S. investments to train and equip them, ANSF and the police still lack our sophisticated counterterrorism tools, not to mention the kind of airpower needed to effectively respond to Taliban insurgent attacks. For much of 2014, the under-resourced Afghan forces suffered heavy losses in battles with the Taliban, who’ve sought to reassert control in their traditional stronghold regions. In addition, about 3,700 Afghan civilians died last year, marking a 25 percent jump from 2013 and the deadliest year for Afghans since 2002.19

Without undermining our commitment to drawdown responsibly, Americans should be sensitive to Ghani’s explicit requests, given the huge challenges that he is inheriting. This would buy him some badly needed time to get his unity government off the ground, giving him a better chance of suppressing Taliban resurgence and stabilizing the security situation.

Conclusion

Afghanistan remains a serious geopolitical challenge with few simple solutions. We are finally drawing down our military forces, but we must remain flexible enough to address the new Afghan government's personal requests for some continued support.