Memo Published January 13, 2015 · Updated January 13, 2015 · 8 minute read

TEACH Grant Trap: Program to Encourage Young People to Teach Falls Short

Tamara Hiler & Lanae Erickson

In 2007, Congress authorized the Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) grant program as a part of the College Cost Reduction and Access Act. The impetus behind the creation of this program was clear—to incentivize our best college students to enroll in high-quality teacher preparation programs and commit to a number of years of teaching service in some our nation’s highest-need schools. Based on data acquired by Third Way under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), as well as publicly available information, it is clear the program is not working and needs to be changed. We found that:

- In just six full years of operation, nearly 40% of students who have been awarded TEACH grants have already had their grants rescinded and converted into unsubsidized loans.

- Overall, the Department of Education expects three out of four TEACH grants to be converted into unsubsidized loans.

- The bulk of TEACH grants have been awarded to students in schools that have poorly rated teacher training programs; very few students in highly rated schools partake in the grants.

We conclude that the TEACH grant program should be overhauled and simplified to fulfill the promise that was made when it was first created: to attract the best students into teaching.

Background: How TEACH Grants Operate

Under the current TEACH grant program, undergraduate and post-baccalaureate students are eligible to receive awards of up to $4,000 per year while in a teacher training program, so long as they maintain a GPA of 3.25 and agree to serve for at least four years in a low-income school and high-needs field. Students can earn up to a maximum of $16,000 in grants—however, the program stipulates that failure to meet all service obligations will result in the conversion of the grant funds into a Direct Unsubsidized Loan with interest charged from the date of disbursement. Thus, if a graduate is unable to find a job in a high-needs area, transfers schools, leaves the teaching profession, or is even laid off due to budget cuts, the grant is converted immediately into a loan with interest.

While other federally-sponsored teacher loan forgiveness programs exist, the TEACH grant program is unique in two ways: 1) it offers money up front to candidates, rather than providing loan forgiveness after the fact, and 2) it is intended specifically to attract the best prospective teachers into the best preparation programs and then encourage them to stay in the classroom.

Findings: Massive Attrition & Low Use at Top Programs

Despite these good intentions, new data secured by Third Way through a FOIA request paints a dramatically different picture of how the TEACH grant program is playing out in reality.

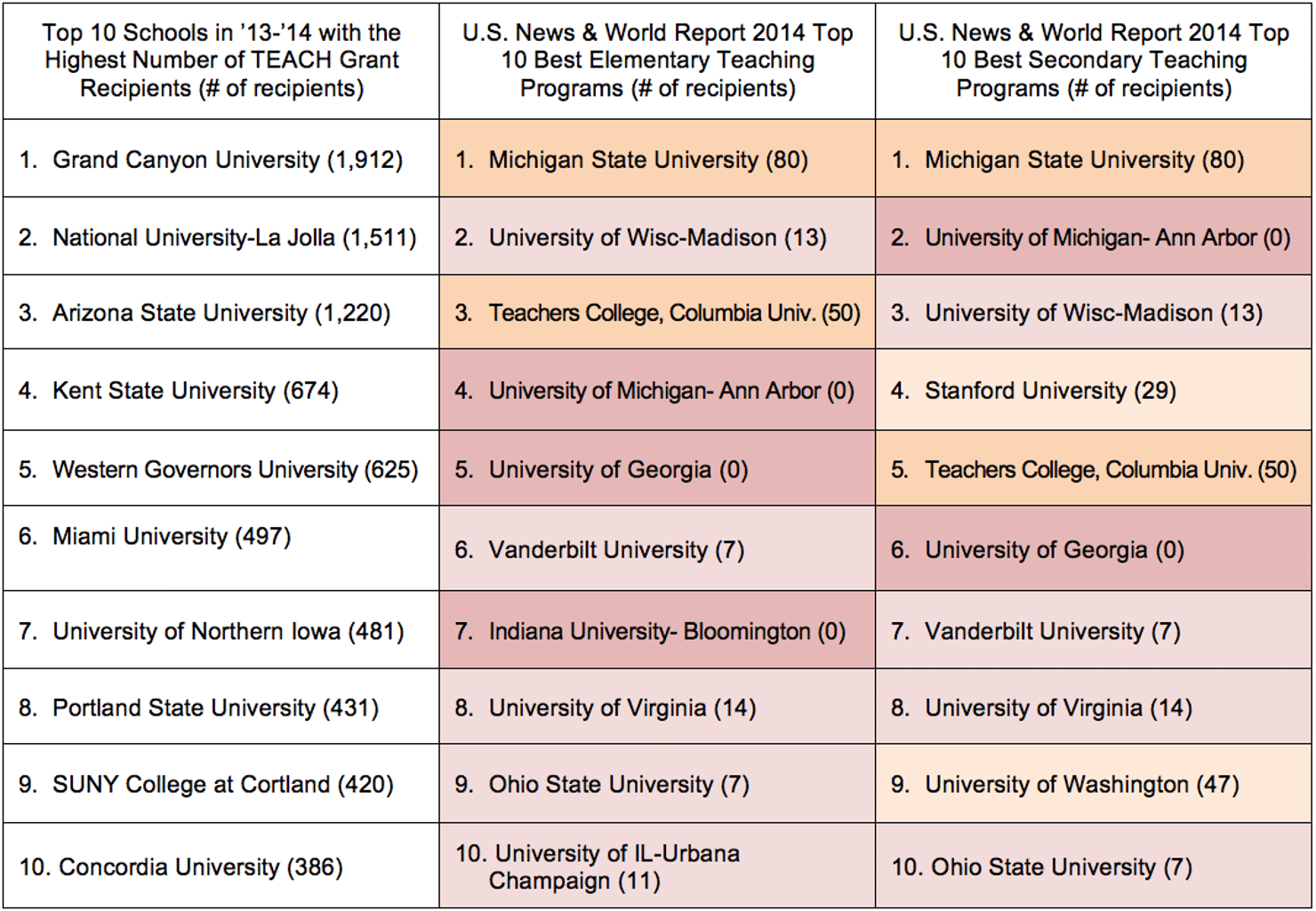

- Since 2008, the first year these grants were offered, there have been 95,379 TEACH grants disbursed—around 15,000 per year.1 Only 60 teacher prep programs out of the almost 5,500 programs in existence (1%) distributed more than 100 TEACH grants this past school year, and of those, not a single one classified as a top-ranking program according to U.S. News and World Report.

- In these first six years, 35,805 (37.5% of the total grants issued) have already been converted into Direct Unsubsidized Loans—a number that is expected to climb as many current grantees have yet to fulfill their service obligations.

- From publicly available information from its 2013 fiscal year budget request, the Department of Education predicts a 75% overall conversion rate—meaning 3 of 4 TEACH grant recipients will end up having to pay them back.2

- For some students, this could put them in an even worse position than if they had not accepted the TEACH grants in the first place (if, for example, they would’ve been eligible for more subsidized loans or financial aid from their institution).

On top of that, data from the Department of Education shows that the programs most likely to utilize TEACH grants are not the top-tier training programs originally envisioned for its use. In fact, for-profit and online universities like Grand Canyon University and National University have dominated the top spot in number of grants disbursed every single year since the program’s existence.3 Of the 38 teacher preparation programs designated low-performing or at-risk through the Title II reporting system (a very alarming classification considering less than a fraction of 1% of all teacher preparation programs even receive such a designation), 22 of them have participated in the TEACH grant program, giving out a total of 1,260 grants in 2011.4 This means that 58% of the worst teacher prep programs in the nation are using federal dollars to recruit aspiring teachers.

On the flip side, of the top-ranked teaching programs listed in U.S. News and World Report, the program with the highest number of TEACH grant disbursements was Michigan State University—which gave just 80 grants out to its students during the 2013-2014 school year (ranking it 81st in highest number of TEACH grants disbursed).5 This number pales in comparison to the 1,912 grants disbursed through Grand Canyon University this same year. Based on publicly-available data, we can see that the schools designated “low-performing” or “at-risk” by the federal government gave out a combined 1,260 grants, while the country’s top performing schools (see chart below) disbursed a significantly smaller number—only 258 this past year. Distinguished teacher training programs like the Teachers College of Columbia University and the University of Washington only gave out about fifty annually. None of the ten remaining top-ranked schools gave out more than 30, and three didn’t issue a single one.

The data is clear: the TEACH grant program—which was well-intentioned in its desire to serve as this country’s marquee financial assistance program for recruiting high-achieving and excellently-prepared teachers—has been a failure in its short six years of existence. A high percentage of students have already dropped out, creating fiscal instability for some students who may have been able to qualify for other forms of financial aid at the outset. Based on the most frequently participating schools, the high conversion rate could be due to teachers feeling woefully underprepared to take on the challenges of teaching in high-needs schools, as there seems to be little assurance that the money is going to effective teaching programs. In general, TEACH grants are failing to incentivize the highest-quality students to enter our classrooms, and it is time for the federal government to reassess the program’s structure in order to better serve its goals.

Conclusion: Revamp TEACH and Other Programs Designed to Attract New Teachers

The federal government has a responsibility to address the shortcomings of the TEACH grant program either by tinkering under the hood to make immediate short-term fixes or, preferably, by completely reshaping the way we provide teachers with financial assistance for their student loans. One short-term fix, which the Obama administration has recently proposed in its new teacher preparation regulations, is to ban low-performing teacher preparation programs from using TEACH grants at all.6 This would be a good start. In addition, Congress could loosen the burdensome restrictions that increase the likelihood of a TEACH grant converting into an Unsubsidized Direct Loan, such as the onerous yearly documentation and reporting requirements, the failure to exempt students who receive reduction-in-force notices during times of forced layoffs (which is highly likely to occur since many districts lay off teachers with the lowest seniority first), or the very short 14-day window students have to change their minds after receiving the grant funding. Congress could also lessen the burden of the 4-year requirement by saying that teachers who leave the classroom before serving four years would have their grants convert to loans on a prorated basis correlating with how long they taught (i.e. 50% would remain grants if they left after two years). All of these short-term fixes would help make the program incrementally more viable for students seeking financial assistance to pursue a career in teaching.

However, these stopgap measures do little to address the long-term goals of attracting high-achieving Millennials into the teaching profession, particularly since there is little agreement at the moment about what constitutes a “low-performing” teacher preparation program, and thus a ban would likely apply to a tiny number of schools. Instead, Third Way has proposed an overhaul of the entire teacher loan forgiveness infrastructure that exists today (the full proposal is available here). We recommend that the federal government consolidate all of the various teacher-specific loan assistance options, including TEACH grants, into one streamlined program that would begin making monthly loan payments for all teachers as soon as they begin teaching. The promise of a supplemental loan payment each month would serve as a strong incentive for high-achieving students to take a serious look at entering the profession, and an even stronger incentive for those already in the classroom to remain past the first few years. Due to current budget restrictions, the federal government could continue to focus this repayment system for teachers who choose to work in the most challenging schools or the most highly-sought after subjects. But even if it were limited to those teachers, as are the current programs, this overhaul would be a vast improvement over the status quo and would provide a much more potent incentive to attract the best and brightest into our classrooms.