Memo Published September 9, 2025 · Updated February 23, 2026 · 13 minute read

Sanctuary Isn’t What You Think

Sarah Pierce

The White House has painted so-called “sanctuary” jurisdictions as lawless safe havens that “harbor criminals” and “block” federal enforcement. The reality is far different. In fact, no state or city stands in the way of federal immigration officers doing their jobs. Instead, local law enforcement agencies make careful choices about how and when they aid federal immigration enforcement—balancing the demands of limited resources, public trust, and local priorities.

Even those that affirmatively call themselves “sanctuary” jurisdictions participate in federal immigration enforcement in meaningful ways. For example, every jurisdiction shares data with the FBI that gets run through ICE and informs the agency of unauthorized or potentially removable immigrants in custody. But the Trump administration’s aggressive focus on ensuring local participation in federal immigration enforcement begs the question of how far Washington can go to force local police to serve as a national force—and what such a power grab risks.

In this paper, we explain the different ways states and localities tailor their participation in federal immigration enforcement, including highlighting the ongoing participation of several of the administration’s most vilified, so-called “sanctuary” jurisdictions. We also explain why some jurisdictions limit or tailor their enforcement more than others and what local public safety measures may be lost as a result of the administration’s hyper-fixation on hitting numerical deportation quotas.

Types of Local Law Enforcement Participation in Immigration Enforcement

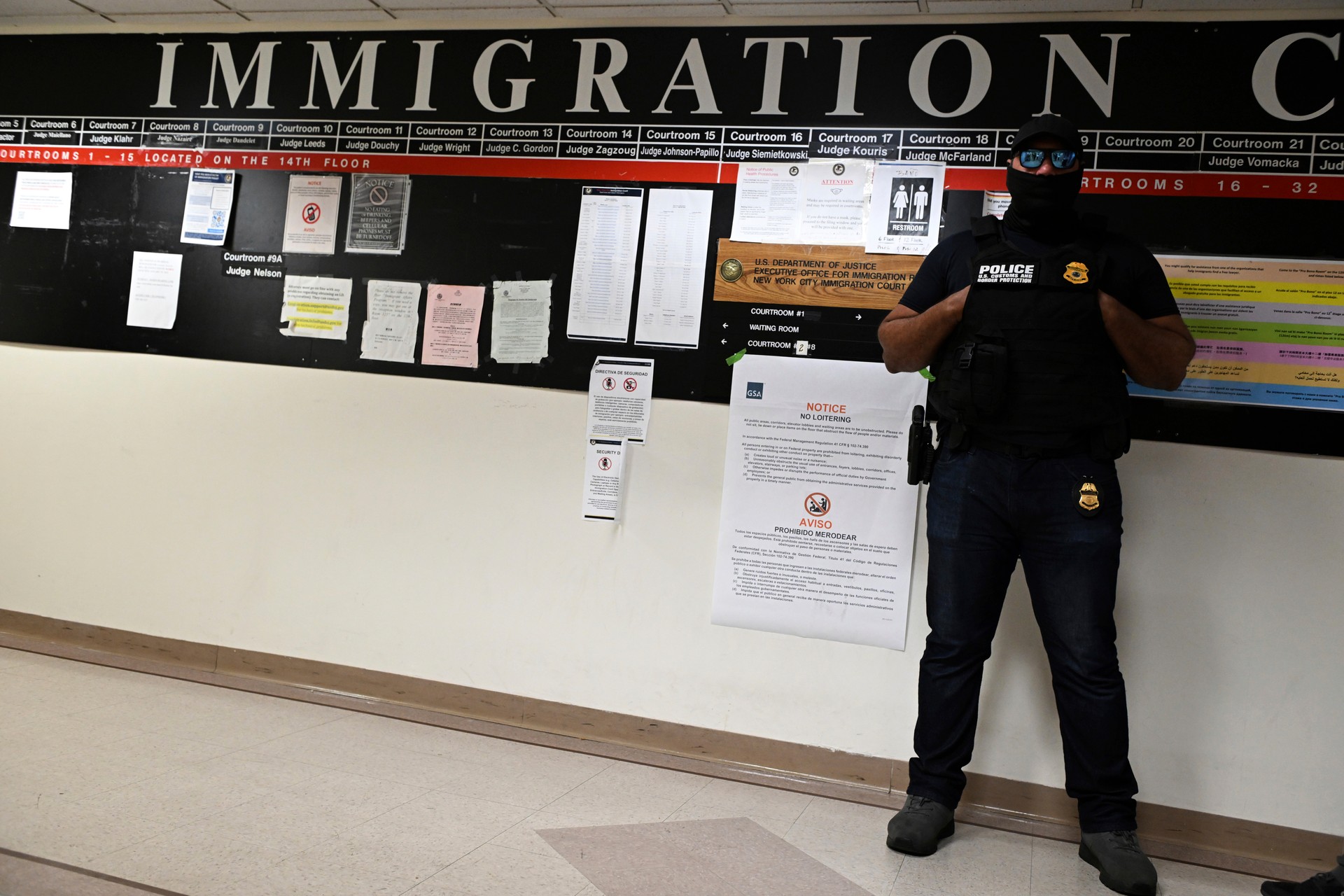

While ICE arrests “at-large,” at worksites or in the community, have been increasingly grabbing headlines, most ICE arrests occur through a transfer from local sheriff’s or police departments. Arresting noncitizens while they are in law enforcement custody allows ICE officers to conduct their work in a safe and controlled environment instead of in local communities. Such arrests also take far less ICE resources.

In order to increase opportunities for arresting noncitizens while they are still in law enforcement custody, ICE has developed strategies to facilitate information sharing and the transfer of custody from local law enforcement to federal immigration enforcement: fingerprint sharing, detainers, and 287(g) agreements. Right now, every state and local law enforcement agency in the country already participates in at least some of these strategies.

Fingerprint Sharing

Law enforcement agencies, including those in allegedly sanctuary jurisdictions, automatically share fingerprints with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI then queries the fingerprints against DHS databases, including the Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) which, among other things, gives any available immigration-related information on the individuals and shares the information with ICE. If the checks reveal that an individual is unlawfully present or otherwise removable, or they return inconclusive, ICE may then take an enforcement action, such as issuing a detainer request to the original law enforcement agency.

Before these systems were fully interoperable nationwide, jurisdictions had to opt-in to the information sharing through ICE-run programs like Secure Communities or, under the Obama administration, the Priority Enforcement Program. However, now, these checks occur nationwide, including in allegedly sanctuary jurisdictions, simply as a matter of course.

Detainer Requests

An immigration detainer is a request from ICE to federal, state, or local law enforcement agencies asking them to notify ICE before releasing a noncitizen and/or to hold the noncitizen for up to 48 hours beyond the time they would normally be released. These requests give ICE time to assume custody of the noncitizen for the purposes of immigration enforcement actions.

All law enforcement agencies from coast to coast honor ICE detainer requests that are accompanied by judicial warrants. However, non-judicial or administrative ICE detainers have raised due process and constitutional concerns. In abiding by such requests, law enforcement agencies run the risk of litigation and liability for damages. Some courts have restricted ICE’s ability to issue detainers to certain state and local law enforcement agencies. As a result of these and other concerns, some jurisdictions have limited how, when, and whether they agree to non-judicial ICE detainer requests—meaning ICE doesn’t have a warrant.

287(g) Agreements

Since 1996, the federal government has let states and localities volunteer to enforce federal immigration laws. Under 287(g) agreements, ICE can deputize local police to act as immigration agents—effectively doing ICE’s job for them. The Trump administration has supercharged the program: as of this publication, the number of active agreements has exploded from 135 to 1,427, so far during Trump’s second term, far eclipsing the previous high of 150. With funding provided by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, ICE is now offering full reimbursements for participating agencies for the annual salary and benefits of each eligible trained 287(g) officer.

These agreements fall under one of three models:

- The Jail Enforcement Model deputizes local police to interrogate suspected noncitizens in criminal custody about their immigration status and issue detainers to hold noncitizens for up to 48 hours after they would otherwise be released;

- The Warrant Service Officer program trains, certifies, and authorizes select police officers to execute ICE administrative detainers but not to interrogate suspected noncitizens about their immigration status; and,

- The Task Force Model allows local law enforcement agents who encounter suspected noncitizens during their daily activities to question and arrest individuals they believe to have violated immigration law, as well as to issue ICE detainers, arrest warrants, and search warrants.

Under the Obama administration, the Task Force Model had been discontinued following allegations of racial profiling and other civil rights abuses. However, the Trump administration has not only resurrected but seems to be promoting the model. Agreements under the Task Force Model have made up 60% of the increase in 287(g) agreements so far in Trump’s second term.

Jurisdictions that Limit or Tailor Participation

Source: NYC Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs, " Sanctuary City Laws in NYC. "

There is no federal law requiring state or local police to participate in immigration enforcement. However, because cooperation with local law enforcement significantly improves ICE’s ability to accomplish its work, every jurisdiction helps—at least in part.

The Trump administration has attempted to smear places that set limits on participation as “sanctuaries.” Yet its own actions show how flimsy that label is. In May, DHS published a list of “sanctuaries” that named 14 states, 415 counties, and 227 cities—only to delete it after heavy backlash. Three months later, DOJ published a different list with 13 states, 4 counties, and 18 cities, without explaining the differences. What both lists ignored is that every jurisdiction on both lists already spends resources helping ICE. Calling them obstacles to enforcement erases the fact that participation in federal immigration enforcement is voluntary, layered on top of the everyday work of keeping their communities safe.

Below, we spotlight some of the jurisdictions branded as “sanctuaries” and provide examples of the ways they cooperate with ICE.

Federal Immigration Enforcement Participation of Alleged “Sanctuary” Jurisdictions

| Jurisdiction | Trump Administration Attacks | Examples of Immigration Enforcement Participation |

| Boston |

|

|

| California |

|

|

| Illinois |

|

|

| Los Angeles |

|

|

| Minnesota |

|

|

| New Jersey |

|

|

| New York City |

|

|

| Nevada |

|

|

Sources: Boston, 11-1.9 Boston Trust Act; California, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Interaction with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; California, Senate Bill No. 54; District of Columbia, Sanctuary Values Amendment Act of 2019; Illinois, Illinois TRUST Act; Los Angeles, Final Ordinance No. 188441; Minnesota, Advisory Opinion of Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison; New Jersey, Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive No. 2018-6 v2.0; New York City, New York City Administrative Code §§ 9-131, 9-205, 14-154; Nevada, “Does Nevada identify as a sanctuary state?”

The Impact of Participation in Federal Immigration Enforcement

While some jurisdictions openly label themselves as “sanctuaries” to appeal to immigrant communities, all jurisdictions decide on their degree and type of participation by weighing multiple factors. Local governments and organizations representing law enforcement have warned that when deciding on the level of participation with immigration enforcement, community trust, witness reporting, scarce resources, and constitutional and civil liabilities are all major factors:

- The Major Cities Chiefs Association (MCCA), a professional organization of police executives representing large cities in the United States and Canada, argues for limiting participation to criminal matters in order to protect trust and cooperation with immigrant communities.

- The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF), an independent research organization focused on policing, has emphasized the importance of distinguishing between local and federal roles, and the risks immigration enforcement presents of chilling victim and witness cooperation.

- The International Association of Chiefs of Police warns that without proper resources, law enforcement agencies may struggle to balance immigration duties with their primary public safety responsibilities, risking compromising overall community safety.

- With MCCA and PERF, the U.S. Conference of Mayors has argued that mandates to participate in federal immigration enforcement force law enforcement agencies to take on potential constitutional and civil liability.

As stated by Hubert Williams, prior president of the National Policing Institute, “Police chiefs must carefully weigh and balance these divergent responsibilities to ensure that the primary mission and purpose of the police department is not compromised by the voluntary assumption of immigration enforcement responsibilities.”

Conclusion

Local leaders have always balanced safety, resources, and trust in deciding how to work with federal immigration enforcement. The Trump administration has thrown that balance aside—branding jurisdictions as “sanctuaries” without evidence and implying they refuse to participate when, in reality, every single one does. Its message is clear: total compliance or face retaliation. Louisville’s retreat under threats of raids and lost funding is a warning—public safety now must compete with political pressure from Washington.

Talking Points

- Local law enforcement has been clear for years: civil immigration enforcement is not a core local police function. The Major Cities Chief Association (MCCA) and other professional bodies have repeatedly warned against diverting local officers from their primary public safety responsibilities.

- Most local police departments simply don’t have the capacity to take on the federal government’s work. Three-quarters of local police departments employ fewer than 25 sworn officers. These are small agencies that focus on core public safety responsibilities. Asking them to absorb additional federal duties risks pulling officers away from responding to crimes, investigating cases, and protecting their communities.

- Republicans keep acting like every police department is a big-city force—but most aren’t. These agencies don’t have spare personnel to take on federal immigration enforcement without sacrificing local public safety priorities.

- Imagine if the IRS demanded that local police help investigate tax fraud—and threatened sheriffs with penalties if they refused. That would be federal overreach. Immigration enforcement is no different—local police should not be coerced into doing a federal government job.

- Local law enforcement agencies prioritize public safety, not politics. Police chiefs and sheriffs know their first duty is to keep their communities safe. They decide how to allocate officers, time, and jail space—balancing cooperation with ICE against core missions like enforcing local laws, investigating crimes, and apprehending offenders.

- These policies are about smart policing, not defiance. Policies that tailor enforcement don’t block ICE—they ensure local agencies operate lawfully, efficiently, and with respect for constitutional limits. Police chiefs must weigh and balance their many responsibilities to ensure public safety isn’t compromised by voluntarily taking on work for federal immigration enforcement.

- Every police department in America helps enforce federal immigration law. There is no city or state “harboring criminals” or standing in the way of federal immigration officials doing their jobs. All jurisdictions participate in federal immigration enforcement to some extent.

- Even jurisdictions that affirmatively call themselves “sanctuaries” participate in federal immigration enforcement. All law enforcement agencies—even those that label themselves as “sanctuaries”—share fingerprints with federal databases, meaning ICE is notified whenever someone is arrested. While this information-sharing used to be limited to jurisdictions that participated in programs such as Secure Communities, it is now operational nation-wide.

- The limits of local law enforcement’s ability to participate in federal immigration enforcement is a bipartisan issue. According to the latest available data, most ICE detainers are not honored, including in red states. In the first month of this administration, in just the state of Texas, more than 3,000 ICE detainers were not honored by local law enforcement.

- There is no federal law requiring state or local police to participate in immigration enforcement. Even though participation in federal immigration enforcement is not required and may divert time and resources from an agency’s primary public safety mission, every jurisdiction helps ICE—at least in part.