Memo Published April 14, 2011 · Updated April 14, 2011 · 7 minute read

Medicare in the Ryan Budget: What it Would Mean for You

The House Republican budget proposed by Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, “The Path to Prosperity,” would make fundamental changes to Medicare.1 As a result, older Americans will no longer have stable and secure health care in retirement:

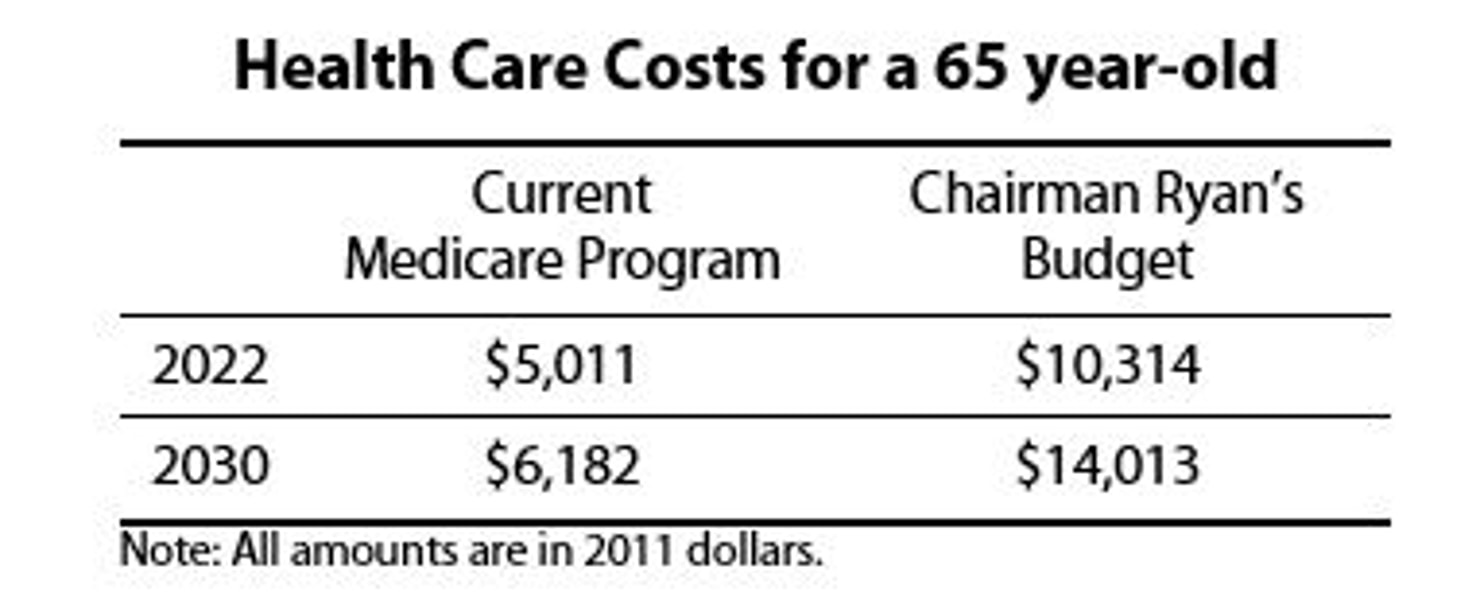

- In less than two decades, a typical senior will have to spend $14,000 for health care, which is $8,000 more than they would otherwise have to pay.

- Barring future retirees from the system would undermine Medicare’s market power and badly hurt current retirees.

There’s no doubt that the rising cost of health care is one of the key drivers of the long-term structural deficit. Changes to Medicare are not only necessary for lowering costs, but desirable for modernizing the outdated way it pays for health care.2 However, by repealing the cost containment breakthroughs in the Affordable Care Act, the Ryan budget has bypassed responsible solutions in favor of drastic change.

What the Ryan Budget Means for Future Retirees

Often, when the Washington policy discussion turns to “cuts,” the debate is really over slowing a program’s absolute growth. The Ryan budget is an exception, and proposes substantial benefit reductions for seniors.

The way it cuts benefits is not a direct path, however. It starts with Americans who are 54 years old today and will turn 65 years old in 2022. They would be the first generation in over half a century that would not be automatically enrolled in Medicare. Instead, they would receive a contribution of $8,000 towards the purchase of private health insurance. As Chairman Ryan explains:

[The budget plan] ensures security by setting up a tightly regulated exchange for Medicare plans. Health plans that choose to participate in the Medicare exchange must agree to offer insurance to all Medicare beneficiaries, to avoid cherry-picking and ensure that Medicare’s sickest and highest-cost beneficiaries receive coverage.3

The irony of Republicans taking the exchange idea from the Affordable Care Act—which the GOP wants to repeal—and using it as a model for Medicare reform is noteworthy, but not the key point. According to an analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, the GOP approach will leave seniors short.4

The $8,000 seniors would receive under the Republican plan is equal to the combined value of Medicare Parts A, B and D (hospital, doctor and pharmacy benefits). However, private health insurance plans won’t be able to offer the same benefits at that price due to Medicare’s low overhead and low payments to doctors and hospitals. Private plans can make up some of the difference through targeted cost control measures, but CBO estimates they will still cost 12% more for the same benefits. Right from the start, seniors would be forced to pay more out of pocket just to keep the level of care they currently receive.

The situation would only deteriorate from there. The initial $8,000 contribution from the government would increase by only the rate of general inflation. If health care costs grow faster than inflation—as they have done historically by leaps and bounds—then the value of the contribution would decline over time. Today, Medicare pays 54% of the cost of private health insurance would cost for a 65 year-old. By 2022, that amount would fall to 39% for the start of the Ryan proposal.

Having started with a benefit deficit, new retirees will soon fall further behind. Competition between health plans vying for the business of seniors will help bend the cost curve, but not enough to bring medical inflation down to general inflation rates, according to CBO.

From 2022 to 2030, the share of the government’s contribution to seniors’ health care coverage will fall from 39% to 32% under the Ryan budget.5 In an analysis similar to one by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, the table below shows the impact on the costs for a typical 65 year-old with Medicare's standard benefits in the first year of retirement.6

The Ryan budget will mean a significant decline in the standard of living for many Americans in their retirement. Supporters of the Ryan budget might argue that people who are 54 years and younger will have time to prepare for the extra cost of retirement. The chances are slim, however, that many people will save extra—because they are not saving enough right now. Only about half of Americans who are 36 to 55 years old are saving enough to meet basic living costs in retirement.7

To illustrate the problem in very rough terms, the Ryan budget will require additional annual savings starting at $6,000 in the first few years and increasing each year beyond that. Assuming no increases, that would be $120,000 for an average life expectancy of 20 years. A 54 year-old would have to save at least $12,000 more per year, meaning 19% less in take-home pay for a someone making the median household income.8

It is more likely that the retirees will turn to their Social Security checks to pay for the additional costs of coverage. The typical benefit for someone retiring in 2030 will be $19,652 (in 2010 dollars).9 The $14,000 in health care costs will consume 71% of his or her Social Security checks.10 And that's on top of out-of-pocket spending for co-pays and deductibles.

What the Ryan Budget Means for Current Retirees

Despite promises to the contrary, current beneficiaries are not protected in the Ryan budget. Under the Republican proposal, traditional Medicare would quickly become second-class medicine. It would “wither on the vine,” as then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich described a similar GOP effort in 1995.

The traditional Medicare plan, which covers three-fourths of today’s beneficiaries, relies on its huge size to keep costs down.11 Doctors and hospitals are not required to participate in it, but they have little choice if they wish to treat any seniors, who are the nation's biggest health care consumers.

Fewer doctors would participate in the traditional Medicare plan if there were an alternative. The traditional plan pays physicians about 20% less than private health insurance plans.12 Today, that is essentially a discount for the large volume of Medicare patients. Under the Ryan budget, it would become a reason for doctors to leave the traditional plan.

By 2030, only 55% of Medicare beneficiaries would still be eligible for traditional Medicare according CBO. Actual enrollment would be less than half of Medicare beneficiaries because many seniors would continue to enroll in private health care coverage under Medicare Advantage. By 2040, traditional Medicare would have only about 20% of Medicare beneficiaries.

Soon after 2040, its purchasing power would shrink to that of Medicaid.13 And its payment rates would likely be similar to Medicaid's because the vast majority of doctors would receive higher rates from private plans. As a result, seniors remaining in traditional Medicare would either have a much more limited choice of doctor, or they would have to pay higher premiums for a private plan with better access to doctors.

The Ryan budget does contain a “hold harmless” provision that will protect seniors from premium increases due to the insurance pool for traditional Medicare becoming older and sicker. But that will not protect seniors from the declining participation of doctors.

Conclusion

To some, the Ryan budget may seem like a "two-fer." It attacks not one, but two great progressive achievements: Medicare and the Affordable Care Act. But even as progressives push back against the ideological framework behind the Ryan budget, we must respond to the challenge with constructive alternatives as President Obama did in his April 14th budget speech. That is the best way to successfully rein in the deficit in a manner consistent with core American values.