Memo Published July 9, 2025 · 16 minute read

How to Finance High Social Value Graduate Training in a New Era of Student Loan Policy

Stephanie Hall

Both the House and Senate have entertained proposals to alter the federal student loan program in recent months, and policymakers will soon be implementing legislation that dramatically restricts access to graduate training programs. The reconciliation bill removes what has been effectively unlimited access to Grad PLUS loans for graduate students and introduces borrowing limits.1 The new aggregate caps will be $100,000 for most graduate students and $200,000 for professional students.2 In this new era, federal and state policymakers and institutions of higher education will need to contend with the effects of constrained access to federal lending. One important area for consideration will be how to address the impacts of these changes on graduate training programs that prepare students to enter fields that provide significant value to society and communities but often lead to lower personal returns. A framework to consider a program’s social value can help conceptualize return on investment and inform further policy reforms to ensure consistent talent supply for in-demand, high-social-value fields.

Growth in Graduate Borrowing

Loans to graduate students account for 47% of all federal loan dollars disbursed, due in part to institutions’ uncapped access to Grad PLUS funds, as well as rising costs for students’ living expenses.3 On average, master’s degree students owe just over $46,000, doctoral degree students owe close to $93,000, and professional degree students owe over $150,000, though these figures vary depending on the field of study and the institution attended.4 For example, over half of all students who complete a master’s degree in education rely on federal student loans, and they borrow an average of around $30,000.5 In contrast, graduate training in fields like law and medicine comes with much steeper costs. Eighty-five percent of law school graduates report borrowing to attend, and the median student borrows over $112,000.6 Notably, first-generation college students who go on to law school borrow $20,000 more on average than their non-first-generation peers.7 Medical school leaves the average student with over $200,000 of education debt, and 71% of all medical students borrow to attend.8

Generally, the longer and more specialized the training, the deeper in debt students can find themselves, though the cost of attendance does not track with eventual earnings in all fields. For example, student debt associated with graduate social work programs is higher than the amount graduate-level teacher trainees take on; social workers hold an average of $51,296 in student loan debt compared to between $25,559–$32,374 for graduate teacher trainees.9 Meanwhile, average social worker incomes are lower than those of teachers.10 The average starting salary for master’s in social work graduates is around $47,000, and the average social worker salary is just over $60,000; for teachers, those figures are $46,000 and $72,030, respectively.11 Graduate social work students of color take on even more debt than their white peers. The same is true for students who train within programs at private nonprofit or highly selective institutions where the cost to attend a social work program can mirror that of law and medicine programs despite the significant gap in anticipated financial returns.12

Potential Outcomes of a Student Loan Overhaul

The reconciliation bill’s architects argue new student borrowing limits will rein in college costs by pressuring institutions to lower tuition to stay within the median cost of attendance, thereby reducing student debt.13 They claim the current system fuels inflation by allowing unlimited federal borrowing, which schools then exploit to raise prices.

Critics contend the policy ignores cost disparities and could harm access for low-income students, particularly in high-need fields like social work or medicine, where debt often exceeds the proposed caps.14 Critics are also concerned that colleges will restrict enrollment for needier students rather than cut costs.

The bill’s theory of action hinges on market discipline, but its success depends on whether institutions

actually

reduce prices.

Another consideration that policymakers will need to contend with is the downstream effect of proposed changes on fields that offer high social value—fields that the public generally agrees are important for societal well-being—but typically lead to lower earnings. Rigid borrowing caps risk excluding students from high-cost, high-social-value fields, unless paired with grant aid or institutional subsidies to offset unmet need. An over-reliance on personal return on investment when judging the creditworthiness of a graduate program’s students, as would likely come to pass if more students in these fields had to turn to the private loan market to fill in gaps, could saddle borrowers with loans with poor terms that don’t align with their earning potential. It could also result in some students being unable to enroll in programs to which they've been admitted if they do not qualify for loans in the private sector. And failing to address this challenge could lead to shortages in critical fields, as students could be deterred from entering those professions altogether.

Troublingly, these shifts could exacerbate inequality, as high-social-value yet low-ROI programs disproportionately enroll women and students who already face wage inequality in the job market. Those students are also more likely to turn to private lenders to fill their funding gaps while enrolled. Calls for wholesale elimination of federal student loans also ignore the costs of underfunding critical sectors. To reconcile these tensions, policymakers and advocates have floated hybrid models like conditional loan allowances and the provision of additional funds directly to programs that demonstrate a certain level of social impact.15

Piloting a framework to test social value-aligned metrics like community impact and employment in high-need fields could inform nuanced funding and lending reforms that ensure taxpayer dollars support both individual mobility and the collective good. Ultimately, the challenge lies in designing higher education finance policies that recognize personal economic and social returns as complementary, not competing, priorities.

Challenges in Measuring Social Value

Measuring the social value of graduate programs is tricky for a few key reasons. First, reliance on hypotheticals can be research-, resource-, and time-intensive because of the challenges of estimating, for example, how much worse off a community might be without social workers. Second, there is no universal way to measure success. Finally, not everyone agrees on what “value” or “social value” mean. Policymakers may care about cost-effectiveness, employers about job-readiness, and the public about community benefits. The definitions of value that prevail or consensus around how to appropriately weigh those various indicators of value will no doubt vary dramatically by program.

As an example, a program training nurses in specialized health fields may have a huge social value according to those personally impacted by related ailments and conditions but a terrible financial return on investment for the graduate. In situations like this, the trainee probably shouldn’t go into debt to attend, but society likely will continue to desire trained professionals in those fields. Access to federal student aid is essentially what is keeping some such programs in business, so current proposals could be the death knell to those programs, if not industries. If there is effective demand, though, completely closing a program may not make sense.16 Instead, a deeper analysis should be undertaken of licensing and credential requirements as well as who—other than the student—could or should foot the bill.

To overcome these challenges, decision makers should use rubrics that:

- Allow for qualitative assessments,

- Require transparency about what is and is not measured, and

- Involve multiple in-field experts evaluating context-specific impacts.

Communicating Social Value

Measuring and communicating social value depend heavily on the audience and purpose. In an environment where not all decisionmakers in control of the public purse will have deep expertise in graduate training, it will be important to express program value in financial or other standardized terms for the purposes of determining appropriate public investment. As an example of how another country has responded to this need, a sophisticated effort to quantify social value in the British health care system (and in British government procurement practices generally) has been underway for some time.17 The social value of National Health Service investments is quantified using frameworks that assess economic, social, and health outcomes like reduced health inequalities, improved workforce productivity, and community well-being. Indirect impacts of investments, like reduced strain on social services and economic gains from a healthy population, are also considered.

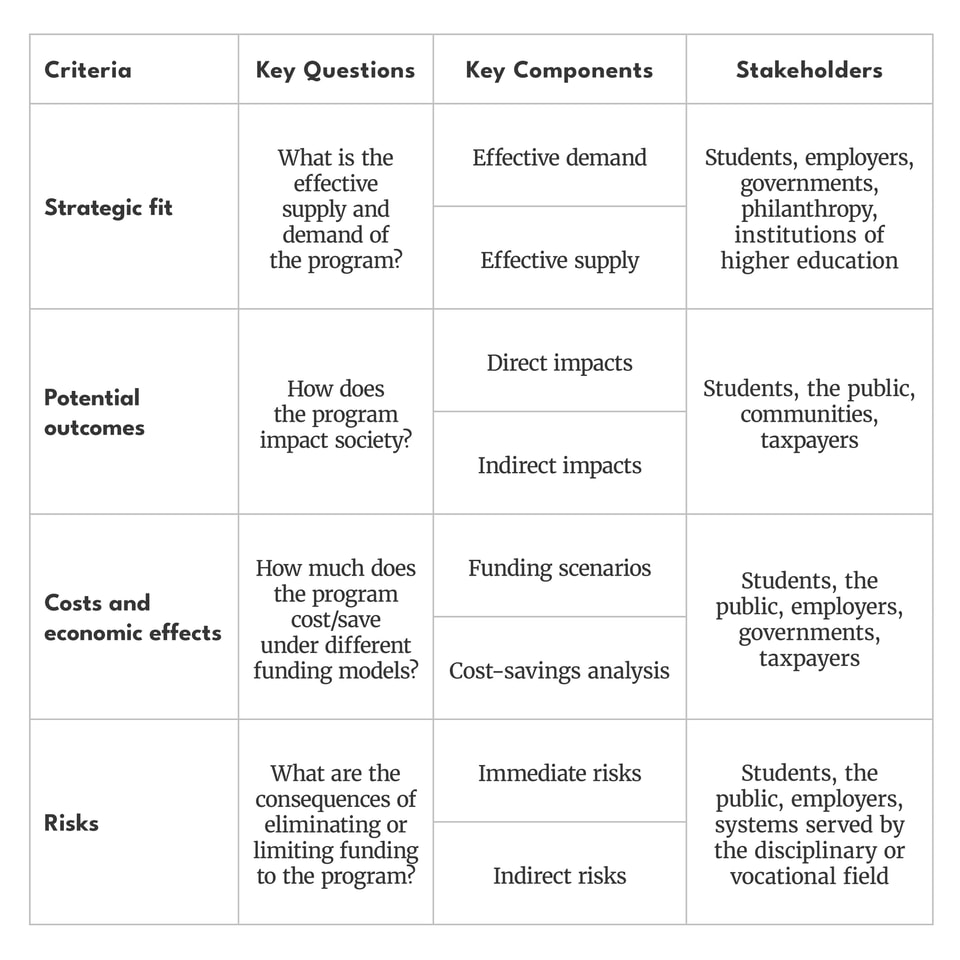

To apply these types of criteria to graduate programs in assessing their social value, policymakers could consider strategic fit, potential outcomes, costs and economic effects, and risks.

Strategic fit: What is the effective demand and effective supply of the program?

In the social policy world, those concerned with measuring social value have taken the market economics concept of supply and demand and broadened it by emphasizing whether each is “effective,” meaning adequate, capable, or functioning.18 In this sense, effective demand is when someone is willing to pay or otherwise provide the resources for a service or a desired outcome. Effective supply is when the service or way to get to the outcome is reliably and consistently available, accessible, and/or implementable.

In graduate education and training, effective demand is present when stakeholders are willing to fund specific training courses. These demand-side stakeholders could be:

- Students paying for personal career advancement,

- Employers sponsoring program enrollment to upskill their workforce,

- Governments funding training in fields that are critical to public priorities, and/or

- Philanthropists supporting the training of those who care for the vulnerable.

Effective supply, then, refers to institutions or other providers successfully making high-quality accessible programs available. Factors that may impact how effective the supply is include:

- Capacity, in terms of sufficient seats, faculty, and other resources;

- Affordability, in terms of there being low or no financial hurdles to enroll;

- Relevance, meaning the curriculum of the program is aligned with things like industry standards and societal needs; and

- Outcomes, which can indicate supply is effective based on things like graduates securing jobs or graduates and employers reporting the training was worthwhile.

As an example, a graduate nursing program may have effective demand by way of hospitals and health systems funding tuition for future nurse practitioners. And there may be effective supply of the programs, which could be evidenced by trainees successfully accessing their coursework, faculty mentors, and clinical training experiences to subsequently secure the relevant licensure.

Despite borrowing from the economics field, this assessment is deeply qualitative and subject to decisions made by those assessing the social value of graduate programs, including whom they consult as part of that assessment. A comprehensive assessment would include consultation with in-field leaders (like professional associations and employers) and state workforce analysts to validate relevance.19

Weak links between effective supply and effective demand don’t necessarily mean a program lacks social value. It could be that there is demand for more highly trained nurses, and the public may see evidence of that demand in short-staffed hospitals. And while a fully-staffed hospital has more social value than one that must turn patients away, the demand for nurses is not yet effective because it is not being effectively (in the sense of successfully, or actually) demanded by a willing investor or consumer. This example illustrates how the public can suffer under ineffective demand–a demand which cannot be or is not being met. Whether programs exist to train nurses or not, if there is no effective demand pulling recruits into those programs, the link to the supply is broken. This kind of scenario warrants special consideration and treatment when determining a program’s current and potential value.

Potential outcomes and impacts: How does the graduate training program in question impact different parts of society?

When considering the social value of a program, policymakers should map out possible direct and indirect impacts of it at different levels of society, including:

- Trainees: Monetary and non-monetary benefits (such as career stability, ability to support families, or social mobility).

- Public/Patients/Clients: Field-specific outcomes (such as student learning gains for teachers or patient health for nurses).

- Communities/Society: Collective benefits (such as a stronger public education system or reduced health care costs).

- Taxpayers: Long-term savings (such as preventive care reducing emergency spending).

Costs, savings, and economic effects: How much money does the graduate training program in question cost and/or save?

Policymakers should compare the financial costs and savings for different segments of society like those listed above (trainee, public, community, taxpayer) under all potential program funding scenarios. These funding scenarios could be:

- Status quo

- A mix of public, private sector, and/or individual investment

- Full private sector investment

- Full public subsidy

The consideration of various finance, funding, and investment scenarios can help policymakers spot overlooked social returns not realized under the status quo or preemptively spot unintended consequences to policy choices. For example, a graduate level social work training program where students currently foot the bill for attendance may be able to realize new returns to the public and taxpayers by shifting some of the financial burden to other stakeholders like employers or governments. The lower financial burden on student-trainees could result in improved work-life balance and an increased ability to be effective on the job, which could indirectly produce value by saving the public money on policing or incarceration.

Risks: What would be the consequences of eliminating, underfunding, or otherwise limiting access to the program?

When considering the social value of a program, policymakers should seek ways to quantify, describe, or capture what would be at risk if a program were eliminated. Policymakers should consider these risks to the program’s immediate stakeholders as well as consider what indirect benefits may be put at risk should students no longer have access to the program. For instance, cutting subsidies for nursing programs could exacerbate staffing shortages, limit access to health care, and raise health care costs.

Assessing the Social Value of Graduate Programs

Applying the above judgements to graduate programs, especially those facing upheaval under revised student loan laws, could guide policymakers toward answers to questions like: Does a program have a high social value? Does it merit increased or decreased public investment? And how much loan debt is realistically appropriate for students in this field to take on given their future earning potential?

Some fields have a higher percentage of students borrowing higher amounts based on associated training costs. Without measures to supplement lost funds or financial support, potential borrowing caps would hastily shut some students out of access to not only lower-paying professions, but also high-earning fields (regardless of social value). An early analysis by the Urban Institute of the College Cost Reduction Act’s student loan limits (which are consistent with those in the reconciliation bill) found that one-fifth of all master’s degree students would have to curb their annual borrowing, while even more students in professional training programs like medicine stand to be negatively impacted.20 Further analysis from the Urban Institute found graduate student loan limits would constrain access to graduate programs at HBCUs.21 This analysis also presented a “loan limit index” in which the higher the index, the higher the share of borrowers borrowing close to the proposed limits. Social work and “other master’s degree” programs were most likely to have high loan limit indexes, while education and teaching programs were lower, potentially indicating the programs are affordable or their typical debt burdens manageable.

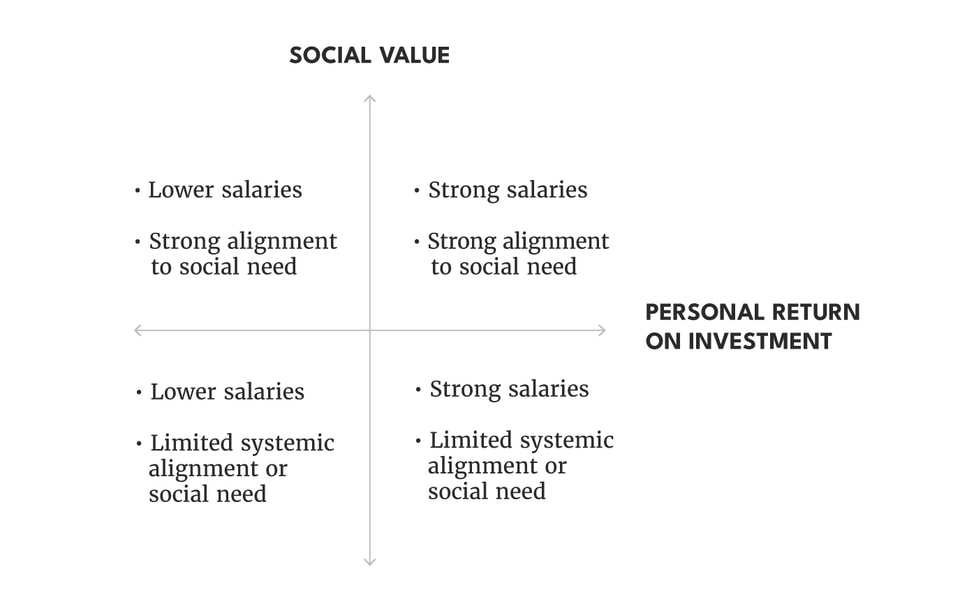

This is where overlaying social value assessments with rates of personal return on investment for the trainee could come in handy. Programs that have a personal return on investment and high social value are those where the graduate or trainee earns strong wages and fills a critical societal need (that also likely has downstream, indirect benefits). Unfortunately, not all programs that provide a personal return on investment offer the same by way of social value. Conversely, some fields we might already consider to be of high social value offer lower salaries and thus have no or a limited personal return on investment for the trainee. The policymaker’s challenge is in resolving these tensions.

The process could also lead to greater involvement of professional associations in validating what is happening in higher education, which could be an overall net positive, since institutional accreditors do not necessarily focus on quality at the program level. Of course, caution must be exercised when tapping professional associations, because they are member-driven and could have an incentive to avoid stringent criticism of programs. Likewise, smaller associations may lack resources for providing consistent input on program value or quality assessments. Associations also have advocacy goals and could face conflicts of interest and biases if given responsibility for high stakes evaluations. Collecting value judgements from multiple perspectives will therefore be key for counteracting risks associated with asking a profession to regulate itself and its access to public resources.

Institutions and state systems are increasingly required to demonstrate both their broad economic benefits (trickle down effects like job creation) and their return on public investment (trickle up effects like taxpayer value). For example, North Carolina A&T State University produced a report to quantify its statewide economic impact, including its value to taxpayers and the public.22 Similarly, states like Kentucky and Tennessee have produced value assessments of their higher education systems with an eye toward taxpayer investment.23 Because institutions rely on state funding and oversight, they and their state partners have a logical role in defining and measuring the social value of graduate training programs for the communities they serve.24

Once high social value programs have been identified, continued support of those professions and their trainees should be prioritized. It could be that concurrent conversations about credentialing and training requirements in certain fields would help policymakers resolve the tension between programs with high social value and limited individual returns. Quick implementation of drastic borrowing limits could result in professional contraction and staffing shortages and upend some fields that are key to social well-being. Assuming the goal of policymakers is not wholesale cuts of programs that are essential for healthy and thriving communities, then implementation of new loan limits should be rolled out slowly, carefully, and accompanied with supplemental funds.

Conclusion

Policymakers should tread carefully when reshaping graduate education financing, as blunt borrowing caps risk excluding students from socially vital but low-ROI fields like social work and teaching. While cost containment is important, solutions should pair measured loan limits with targeted subsidies. Cross-sector input on social value, and protections for marginalized students will be essential to avoid destabilizing essential professions. The challenge—and opportunity—lies in designing systems that recognize both economic efficiency and public good, ensuring access to graduate education remains a driver of both individual mobility and collective well-being.