Memo Published April 9, 2018 · 5 minute read

Bachelor's Degrees May be the Equalizer for First-Generation Students

Michael Itzkowitz

I’m lucky enough to have a better half—my wife, Stefanie. She is amazing and consistently makes me a better person. And I’m not the only one who gets to benefit from her greatness—she works as an assistant principal where she provides opportunities to high school students every day. However, she’s also somewhat of an outlier—her parents never graduated from college and, statistically, she shouldn’t have either.

That’s because according to a new report from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), first-generation students face significantly greater obstacles when it comes to accessing and graduating from college.1 The study, which looked at three groups of students over an extended period of time, compared the enrollment and outcomes for students whose parents never attended college versus those whose parents attended some college, and those whose parents earned a bachelor’s degree. It found that first-generation students that started college were 19 percentage points less likely than other students to still be enrolled in college or to have obtained a college degree.

And completion matters, big time, especially for first-generation students. The study also found that first-generation students who do go on to earn bachelor’s degrees were just as likely to be working in full-time jobs and earned nearly identical salaries as all other students.2 That means college continues to be a great equalizer, but it’s clear that the “leaky pipeline” we already have in higher education is even larger for students navigating postsecondary education for the first time.

So why is this happening and how can we close these gaps?

First-Generation Students are Less Likely to be College-Ready

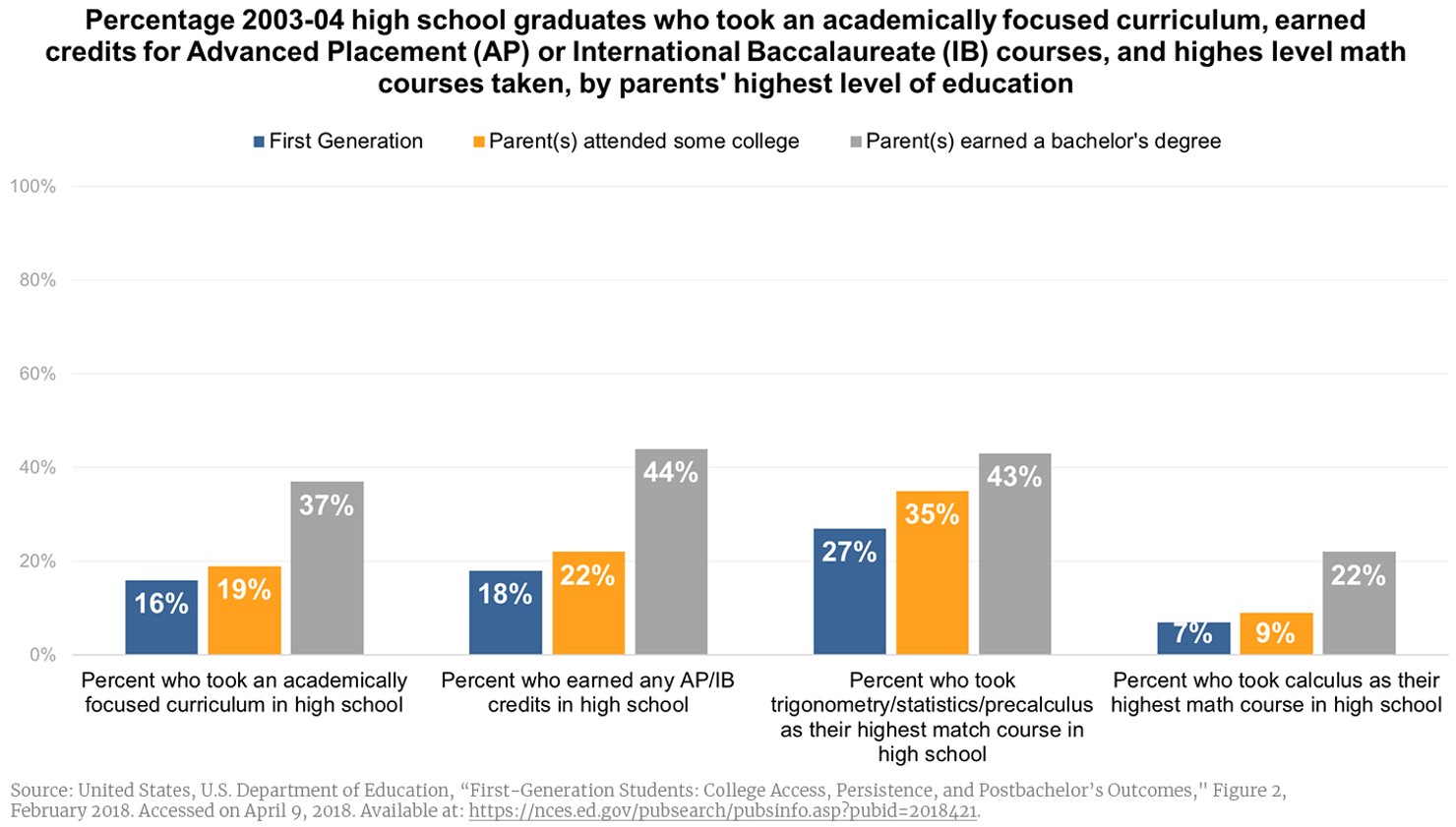

First, the NCES report found that many first-generation students aren’t being set up for success, even before they leave high school. According to the study, first-generation students were less than half as likely as their non-first generation peers to take Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, or college-level math classes. Advanced classes have been shown to not only increase the likelihood of enrollment, but also college completion.3

First-Generation Students are Less Likely to Enroll in College to Begin With

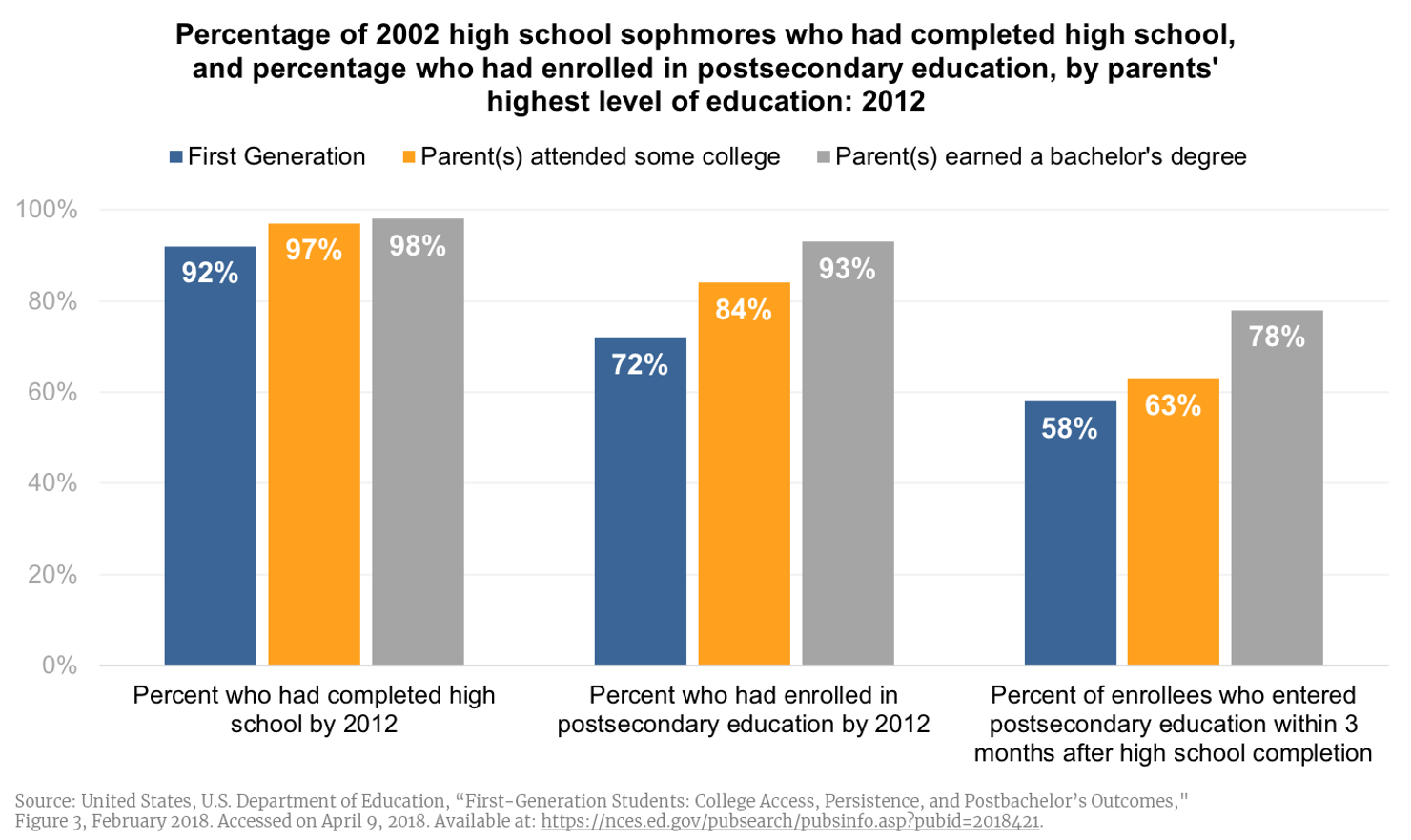

While first-generation students are almost as likely to graduate high school as other students (yay!), a significant portion of these students appear to slip through the cracks somewhere between earning that degree and successfully enrolling in a postsecondary institution. In fact, only 72% of 2002 first-generation high school sophomores had enrolled in any type of postsecondary education program 10 years later compared to 93% of students whose parents had earned a bachelor’s degree.

For first-generation students, they will be the first in their families to navigate the lengthy and often very confusing college application process. This, coupled with less access to and completion of advanced high school classes, may explain some of this enrollment gap.4 Of course, if you never enroll, you can’t graduate—a major factor contributing to lower postsecondary attainment for this group of students.

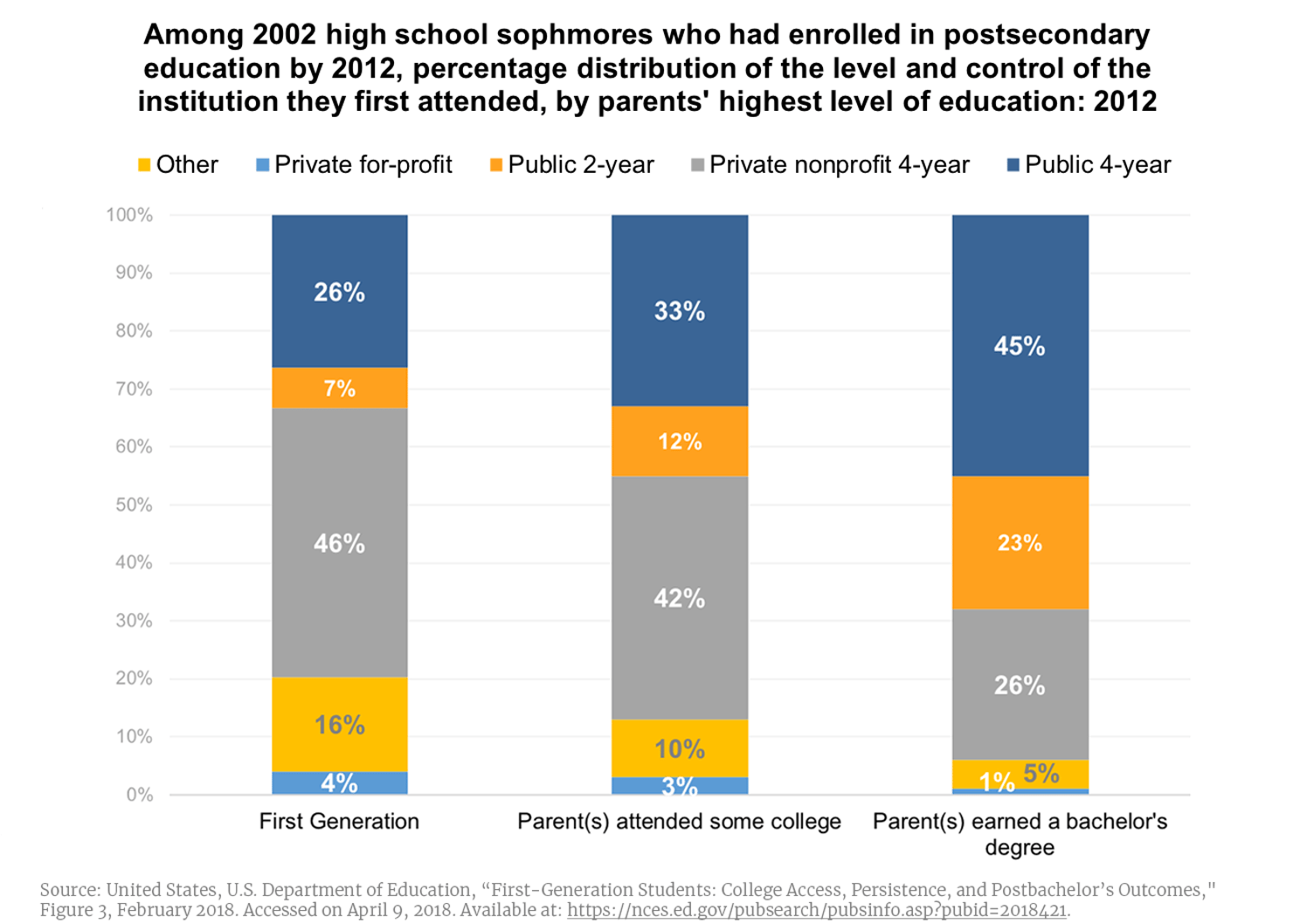

When First-Generation Students Do Enroll, They’re Less Likely to Attend Four-Year Schools

The study also found that first-generation students are also almost twice as likely to enroll in two-year public institutions and are more than three times as likely to enroll at a for-profit institution. Students who attend these institutions are often less likely to complete a degree, earn a modest living, and be able to pay down their education debt after attending.5 Furthermore, those attending two-year institutions are very unlikely to end up with a bachelor’s degree after doing so, as only 14% of students who successfully transferred from a two-year to a four-year institution ended up with a bachelor’s degree within six years of initial enrollment.6 While their choice of institution may be related to lower academic preparedness (or non-acceptance into more competitive institutions), this study suggests that there are also many non-academic obstacles that first-generation students face—including financial barriers, the need for flexible schedules, and child-care.7

The research is clear, we struggle to prepare our first-generation students to enter college, enroll in one that offers them with the best chance of success, and have them leave with a college degree. However, first-generation students who do graduate with a bachelor’s degree in hand show similar economic outcomes as all other students.

As conversations to reauthorize the Higher Education Act continue, college completion must be at the forefront of policymakers’ minds, especially for first-generation students. This study shows that the economic benefits of earning a degree don’t just apply to one group; however, our current higher education system continues to prepare and advantage some groups of students more than others. It’s important that every student has equal opportunities to access postsecondary education and leave with a quality degree in hand. If they did, maybe more students whose parents never earned a degree, like my wife Stefanie, would also be able gain the necessary credentials to succeed in our 21st century economy. And then maybe their children—the next generation of students—would also be more likely to pursue and reap the benefits that a postsecondary education has to offer.