An Even Riskier Bet: Where CARES Act Funds are Headed in Higher Ed

Institutions of higher education have long been in stewardship roles; they’re stewards of research, our nation’s students, and of $120 billion in taxpayer dollars sent yearly.1And most of them perform well in this critical role. They’re incubators for new ideas and they help equip our students with the skills they need to be productive global citizens. But with the amount of public trust and resources we invest in our colleges and universities every year, they all must live up to that task.

This urgency for accountability has grown significantly during the current educational and economic upheaval caused by COVID-19. Since mid-March, nearly all institutions have moved to online-only options, as health concerns are too high to maintain in-person learning environments. Furthermore, nearly 50 million Americans and counting remain out of work, and many may be looking at postsecondary options to upskill for the new economy.

Congress has acted quickly to support students and institutions to keep them both afloat, allocating $14 billion to higher education through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), half of which must be distributed to students in the form of emergency grants that they can use to cover costs related to the outbreak like childcare, food, or technology.2With such a massive influx of money, taxpayers should be able to expect some safeguards are in place to ensure those federal funds flow to institutions that show good outcomes for the students they serve.

With another round of stimulus funding in the works, we decided to look at the first round of CARES funding that was allocated based on student enrollment—regardless of the outcomes that institutions produce for their students. Specifically, we examined this question: “Are these institutions helping students graduate and get a decent-paying job that allows them to begin paying down their educational debt after they attend?” To answer this query, we examined the total federal funding schools received, including funding for emergency grants to students. And while we believe the federal government should continue providing direct assistance to ensure students in higher education aren’t set back by COVID, these initial allocations show why there should be greater scrutiny in future packages. Unfortunately, some of our findings are grim for both taxpayers and students; hundreds of millions in CARES Act funding flowed to institutions that show less than 25% of their students succeeding, and many schools that cashed big checks left the vast majority of their students even worse off than if they had never attended.

College Completion

One of the most important outcomes for students attending an institution of higher ed is whether or not they complete the credential they sought during enrollment. Labor data show that students who don’t complete earn less money than those who do and default on their student loans three times more often—the worst of the worst-case scenarios.3Unfortunately, many institutions fail to deliver to its students a real chance at graduating, leaving most who enroll without any sort of credential. Even so, these schools still received hundreds of millions in taxpayer funds through the last round of COVID-stimulus funding.

In the first round of stimulus funds allocated to colleges, $479,974,057 went to 172 institutions that graduate less than 25% of their students.4Alarmingly, 19 of these institutions only graduate less than 10% of their students, meaning 9 in 10 are left without a credential, and each of these schools received an average award of approximately $1 million. Considering that the average graduation rate among these 19 schools is only 4%, policymakers should be asking whether or not they are the best stewards for additional taxpayer funds through this crisis.

One institution that falls into this boat is South University, a for-profit, four-year college located in Savannah, Georgia. In the most recent round of CARES Act funding, this institution received $7,726,176. But, only 2,197 out of 15,832 (or only 14%) of the students attending this college completed in 2018. Providing a massive influx of federal funds to institutions with abysmal completion rates is unlikely to 1) improve student outcomes and 2) provide taxpayers the return on investment they expect from investments in higher education.

Employment Outcomes

The number one reason why students pursue higher education is to land a decent-paying job that allows for a financially secure future.5With millions of Americans recently out of work, this promise of security and mobility becomes most important, as many will flock to schools to reskill or upskill during the economic downturn. One way to gauge if institutions are succeeding in this mission is to explore whether or not their students actually earn more years after they’ve enrolled compared to those who never attended college (a figure calculated by the Department of Education (Department) to be $28,000, the average earnings for a high school graduate).6Unfortunately, many higher education institutions do not meet this mark, failing to equip their students with the necessary skills to earn even a modest living.

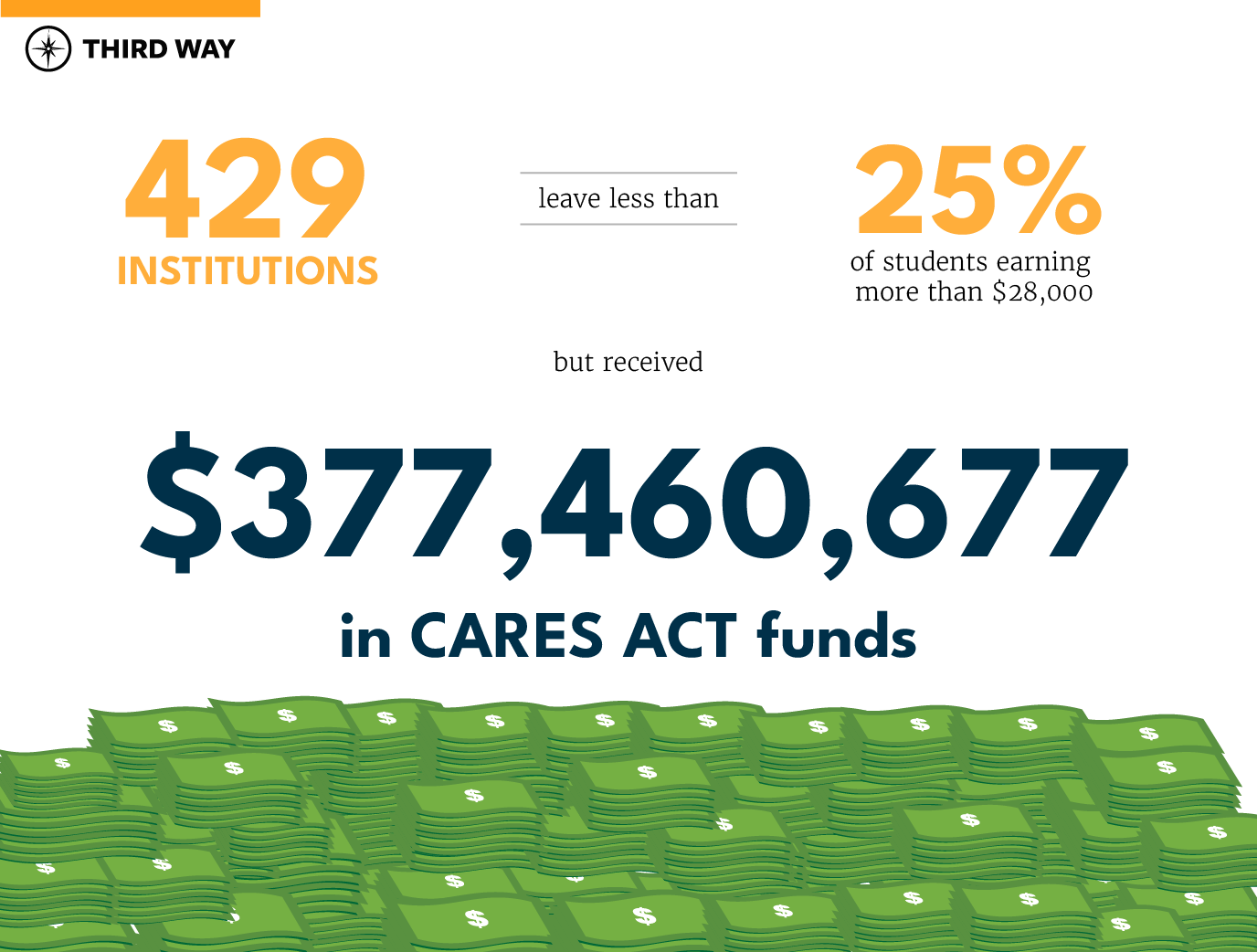

Federal data show us that out of all institutions receiving CARES Act stimulus dollars, 429 schools see less than 25% of their students earning more than the average high school graduate, six years after enrollment.7In fact, only 18% of students attending these colleges earn more than that $28,000 mark on average. Even with poor employment prospects for their former students, these institutions still received $377,460,677 in stimulus dollars in the first round of CARES Act funding. Even worse, 21 institutions (that cumulatively received over $7 million) show less than 10% of their students earning more than the average high school graduate six years after enrolling in school. On average, only 8% of the students who attended these institutions were able to hit this minimal economic benchmark and earn more than $28,000 years after attending.

One of these institutions is the Nouvelle Institute, a for-profit, less than a two-year institution in Miami. This college was allocated $805,020, with $402,510 set aside for emergency grants. Yet only 8% of its students earn more than $28,000 six years after graduation. Congress should consider whether students attending this institution and schools like it are truly receiving a return on investment before sending more taxpayer money to bail out these colleges.

Loan Repayment Outcomes

To finance their postsecondary education, most students rely on federal loans to help cover the costs, averaging around $30,000 for bachelor’s degree recipients.8With nearly $100 billion in federal student loans going to institutions yearly, they must be used efficiently to benefit the students these schools are intended to serve. Students should be able to earn the credential for which they enrolled and get a job that allows them to pay their loans back so that taxpayers can get a return on this massive federal investment. Unfortunately, many institutions leave students unable to even begin making a dent on their loan principal, meaning they owe even more years later (due to accumulating interest) than they did when they left the institution. To measure whether CARES recipient colleges are setting students up to earn enough to pay down their educational debt, we looked at the percentage of students who have been successful in paying down at least $1 on their loan principal within five years of leaving, a basic benchmark to determine whether institutions are preparing students for success.

Just as we saw with completion and employment outcomes, many institutions do deliver on this promise, but, unfortunately, far too many leave their students with unmanageable debt. In fact, 171 institutions receiving CARES Act funding showed more than 75% of their students unable to pay at least $1 toward their student loan principal within five years of leaving the institution. Despite that, these colleges were provided $254,025,266 in the last round of COVID-stimulus funding. Two schools even displayed loan repayment rates of less than 10% yet they were eligible for $306,105 in stimulus funds.

One institution shown to leave most of its students struggling with debt payments is UEI College, a for-profit, two-year college located in Fresno, California. Our findings showed only 18% of its students able to begin paying down their debt within five years of leaving, yet this school still received $5,025,381 from the stimulus bill. If policymakers are going to invest further federal funding to support colleges during this difficult time, they should target institutional aid away from schools that leave most of their students in debt they cannot afford to repay.

Conclusion

The first $14 billion in CARES Act funding needed to get out the door quickly and policymakers prioritized that goal. Yet funding from the CARES Act is insufficient to fully meet the needs of students and colleges looking to recover from the pandemic’s fallout, so additional relief will be needed to keep institutions afloat. In this next round of aid, taxpayers and students alike should be able to feel confident that Congress will direct tax dollars toward institutions that leave their students with a worthwhile credential which prepares them for a financially secure future. If a school hasn’t done that in the past, it is unlikely to do it in the future, especially if Congress fails to pair an influx of money with guardrails and consumer protections. As policymakers continue to respond to COVID-19 and the economic shocks brought along with it, they must find a better way to target funding toward institutions that have been shown to provide students with a high-quality education, rather than propping up schools that leave most of their students worse off than when they enrolled.

Endnotes

Office of Federal Student Aid. “Title IV Program Volume Reports,” U.S. Department of Education, 2020, https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/title-iv. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

U.S. Department of Education. “CARES Act: Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund,” U.S. Department of Education, 2020, https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/caresact.html. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

Carnevale, Anthony P, Cheah, Ban, and Rose, Stephen J. “The College Payoff: Education, Outcomes, and Life Earnings,” The Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, 2011, https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/the-college-payoff/. Accessed 30 Jun 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Education matters,” U.S. Department of Labor, Mar 2016, https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/data-on-display/education-matters.htm#:~:text=According%20to%20data%20from%20the,than%20those%20with%20less%20education. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

This paper uses data from the College Scorecard, the Office of Federal Student Aid, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), and the Performance by Accreditor Data File. Original analysis was conducted by the author to compile the data set using a six-digit institutional identifier from the Office of Federal Student Aid. Eight-year completion rates come from the Department’s Outcome Measures survey and removes transfer-out students from the numerator and denominator completely instead of treating them as a failure. Loan repayment rates measure the percentage of students who have paid down at least $1 on their loan principal within five years of leaving school and entering repayment on their federal student loans.

Eagan, Kevin. “The American freshman: National Norms Fall 2015.” Cooperative Institutional Research Program at the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA, https://heri.ucla.edu/pr-display.php?prQry=196. Accessed 10 Jul 2020.

The threshold earnings metric is calculated by the U.S. Department of Education to be $28,000 per year within six years of leaving.

Only 18% of students attending these colleges earn more than $28,000 on average.

The College Board, “Trends in Student Aid 2019,” The College Board, Nov 2019, https://research.collegeboard.org/trends/student-aid/highlights. Accessed 2 Jul 2020.