Memo Published December 30, 2019 · 16 minute read

A Nuanced Picture of What Black Americans Want in 2020

Ryan Pougiales & Jessica Fulton

This fall, Third Way and the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies launched a multi-round research initiative to study the attitudes, priorities, and values of Black Americans as we head into a major crossroads for our country in 2020. The impetus for this effort was to help address the dearth of public opinion research on Black people in this country by digging underneath the surface to understand nuances based on attributes like age, education, gender, income, and urbanity. Rather than looking at a small oversample to make broad generalizations about what all Black people think, this research captured similarities as well as key differences between subgroups.

The banner finding from this research is self-evident to most Black Americans, but unfortunately, it goes too often overlooked by political pundits, policymakers, campaigns, and the press alike: Black people are not monolithic.

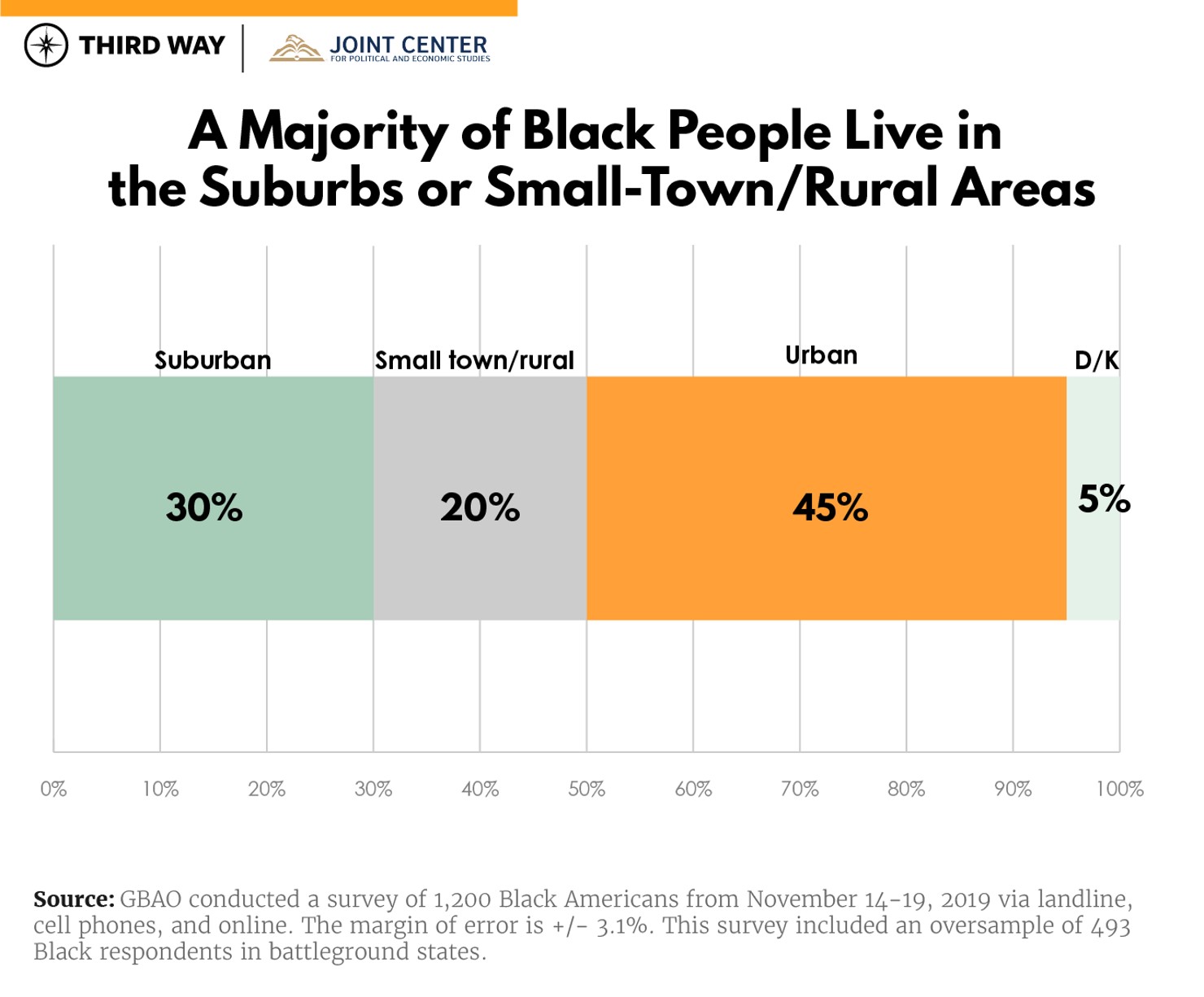

- Black people in America have different identities and experiences. For example, just 45% in the survey live in cities. A majority live in suburbs, small towns, or rural areas. Twenty-two percent have a four-year college degree, but another 37% have some amount of post-secondary education. Among the employed, one in five works more than one job. A third of people go to church every week.

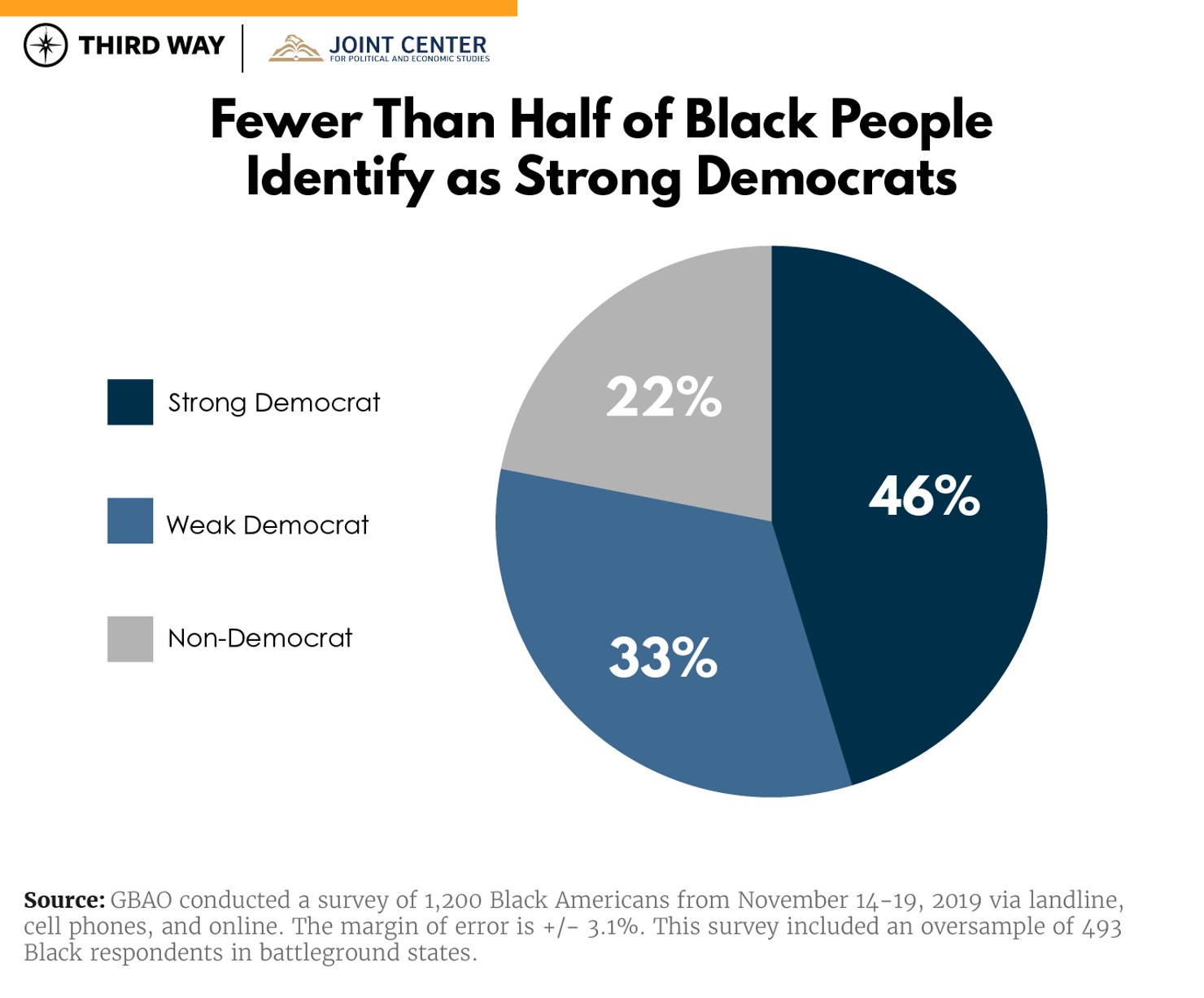

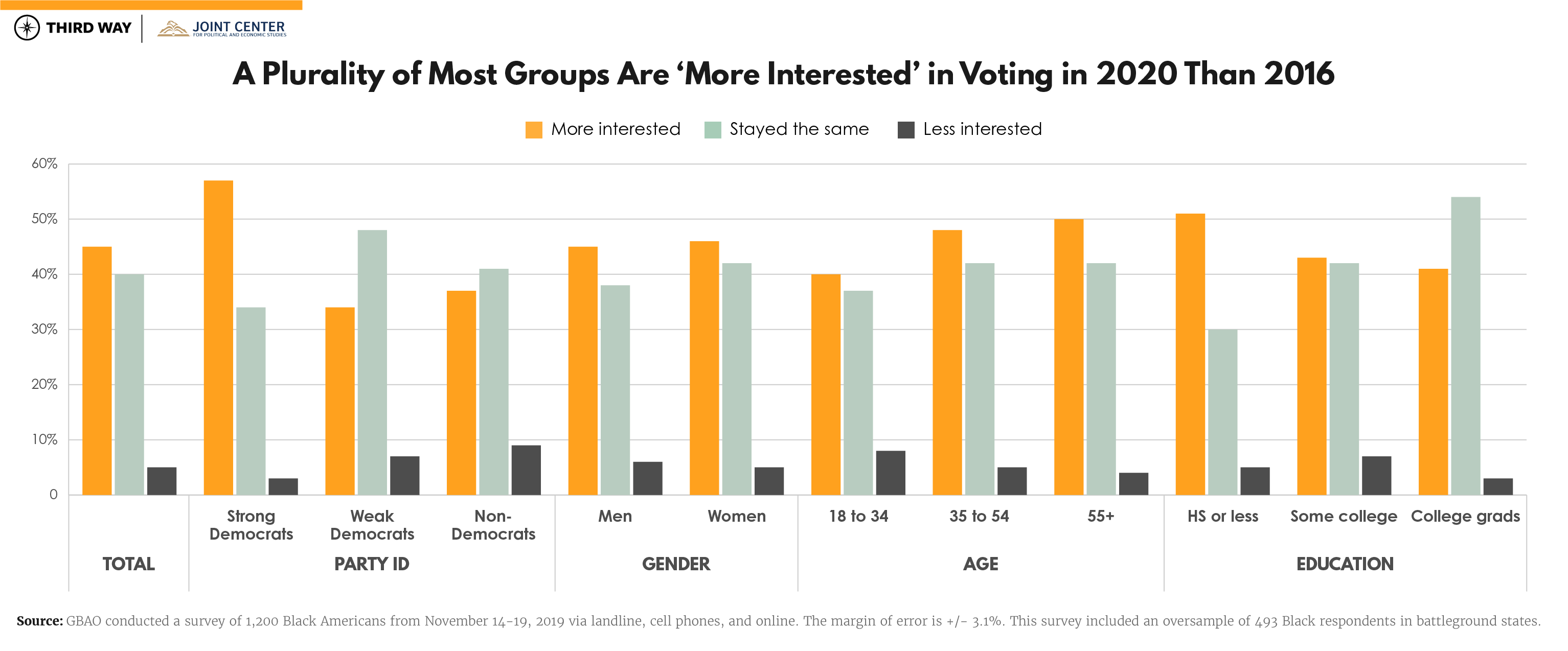

- Feelings about the 2020 election vary. Forty-six percent identify as strong Democrats, and 57% of them are more interested in voting next year than they were in 2016. But this share drops to 34% with the one-third of Black people who are less attached to the Democratic Party.

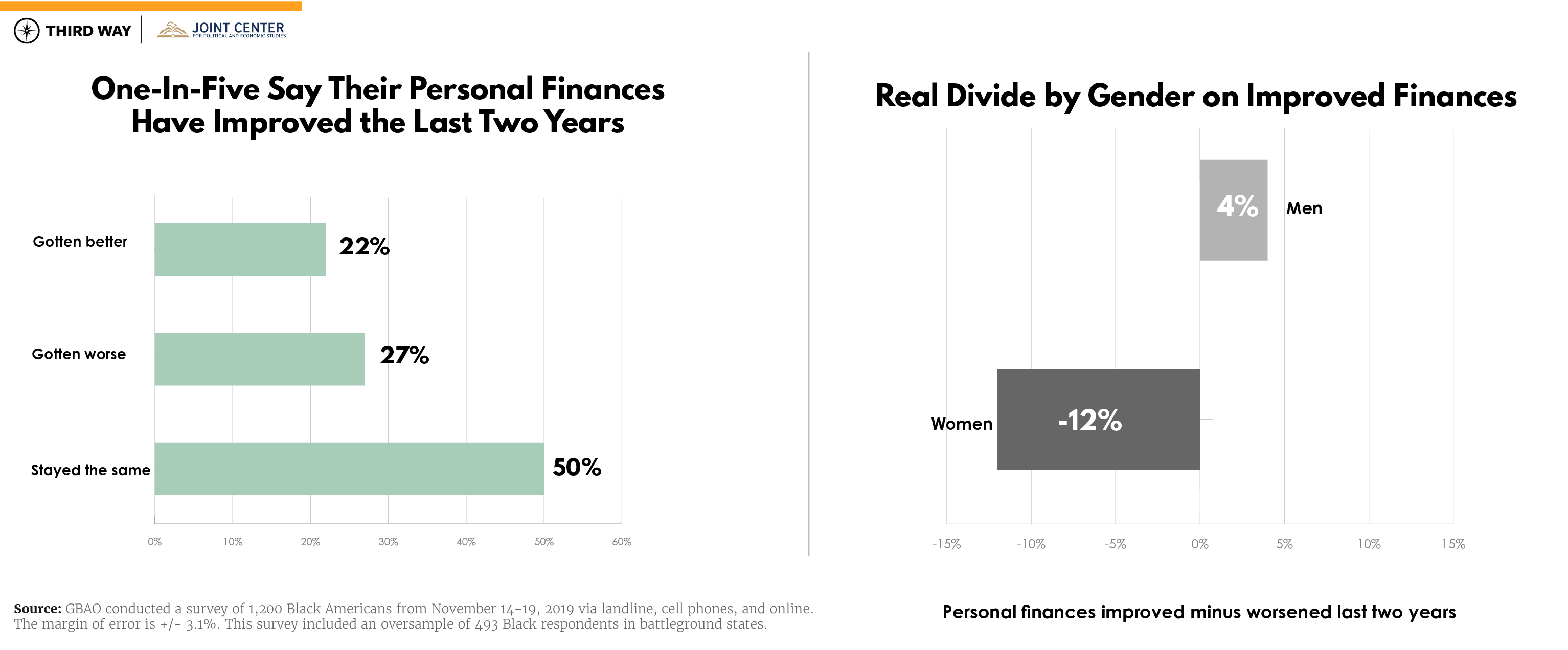

- Financial situations and priorities differ. Just 22% of Black Americans say their finances have improved over the last two years, but women are 11 points more likely than men to say their situation has worsened. Black people prioritize kitchen-table issues and urgent priorities, but not always the same ones. Women’s top priority is affordable housing while men’s is health care costs.

- Feelings about race and racism are complex. Eighty percent of Black Americans say that Trump’s election has made people with racist views more open to expressing them. But college grads are 19 points more likely to believe this than those with a high school degree or less.

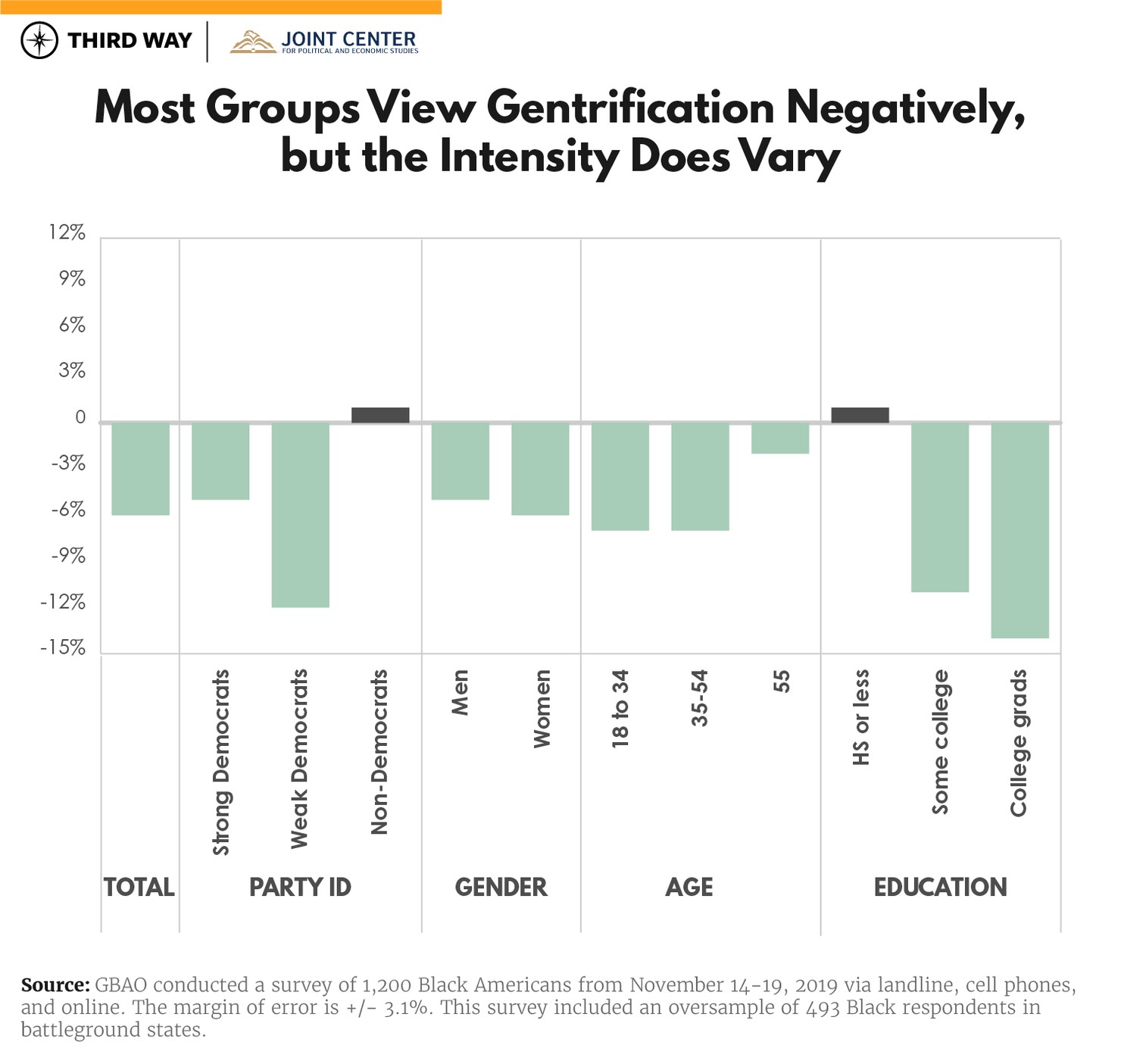

- Gentrification is impacting people in different ways. Gentrification was brought up by participants in all nine of our focus groups. And views on it do vary. Black people who live in suburbs believe gentrification has done more harm than good by 16 points, but this margin narrows to four points with city dwellers.

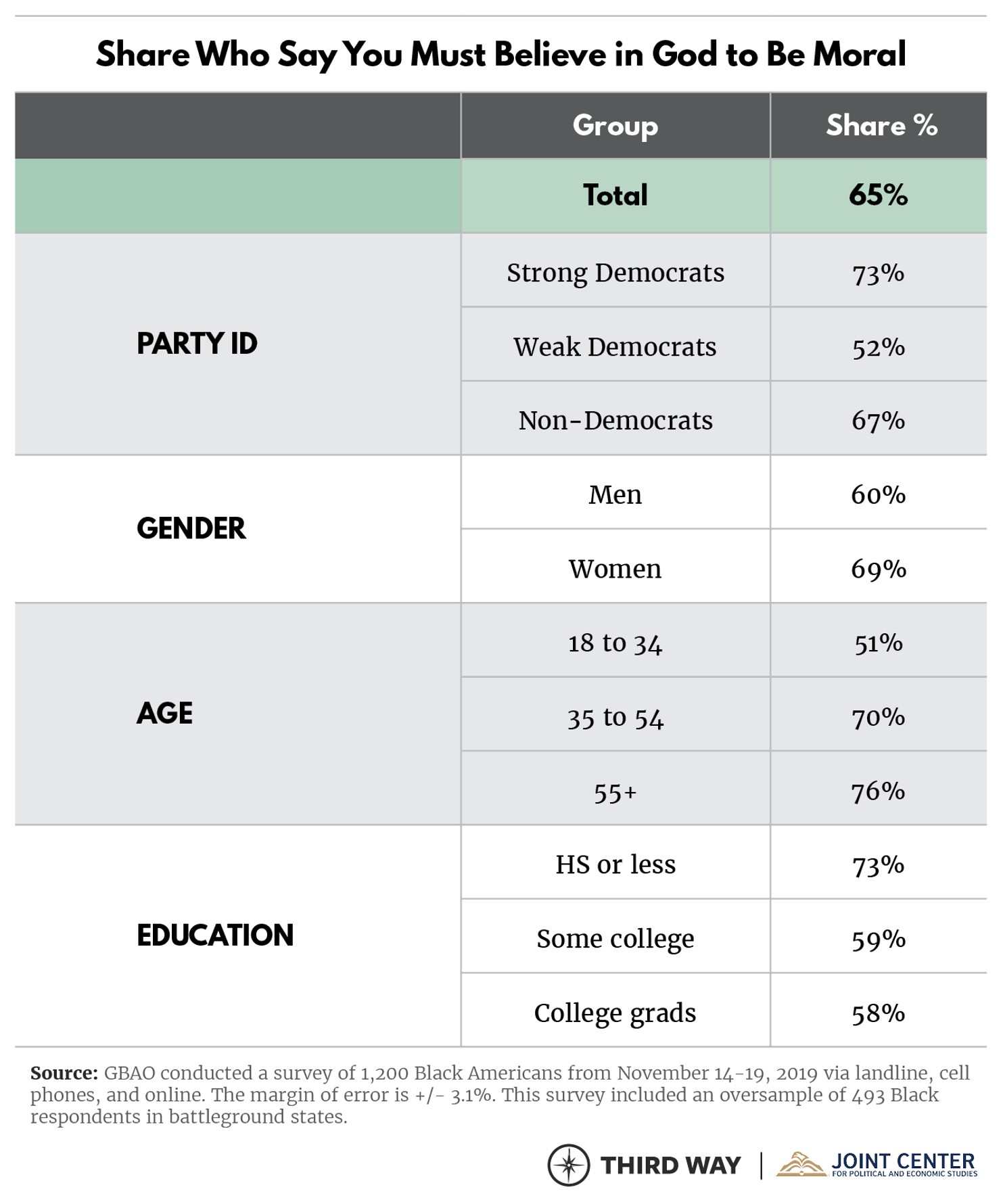

- Views on values differ by age and education. Young Black people, especially those with college degrees, are more likely to side with values associated with liberals. For example, those over 55 say you must believe in God to have good morals by a 54-point margin. But a slim majority of young college grads reject this notion.

By better understanding Black voters and non-voters’ attitudes, priorities, and values, policymakers and pundits alike can ensure that they are responsive to Black people—not just to the stereotype of what they assume Black people care about across the country.

Digging Beneath the Black Polling Crosstab

Black people in America obviously have a diversity of identities and experiences. But often in public opinion research, they are lumped together with a tiny sample size in an amalgamated category of “Black,” or sometimes the even vaguer “people of color.” This obscures important distinctions among Black people, despite the fact that understanding these differences is essential to addressing their range of priorities and effectively engaging them in the political process.

Some assume that a majority of Black people live in urban areas. But when looking at the respondents in our survey, 45% self-identify as living in cities, 30% in suburbs, and 20% in small towns and rural areas. That means the majority of Black people live in non-urban areas today. Half rent and half own their homes.

One in six are children of immigrants, with half coming from the Caribbean and the next largest concentration from West Africa. Seventy percent affiliate with a Christian denomination, and a third attend church every week.

Nine in 10 people in the survey indicated they are registered voters. Many assume that Black people universally identify as Democrats, and most do: 79% self-identify as Democrats. But 46% are strong Democrats, while 33% identify as weak Democrats (including Independent leaners). Weak Democrats are 53% male, nearly half are under 35, but fewer than one in three have a high school degree or less. The remaining 21% do not identify as Democrats at all.

These divergent identities and experiences illustrate just some of the complexities and cross-currents among Black people in America. Throughout this analysis, we will focus on the subgroup categories of gender, education, age, and partisan self-identification to bring some of these complexities to light.

A Diversity of Black Views on 2020

Generally, Black people across the country are pretty engaged ahead of the 2020 election. But important distinctions come out on enthusiasm compared to 2016. Among all respondents, 45% are more interested in voting in 2020 than they were last time around, while 40% have the same interest, and 5% are less interested. But partisan self-identification is a key lens for this question: 57% of strong Democrats say they are more interested than they were in 2016, but this share dips to 34% among weak Democrats. Educational differences also highlight a real split: 51% of people with a high school degree or less are more interested in this coming election than they were last time around, compared to only 41% of college grads.

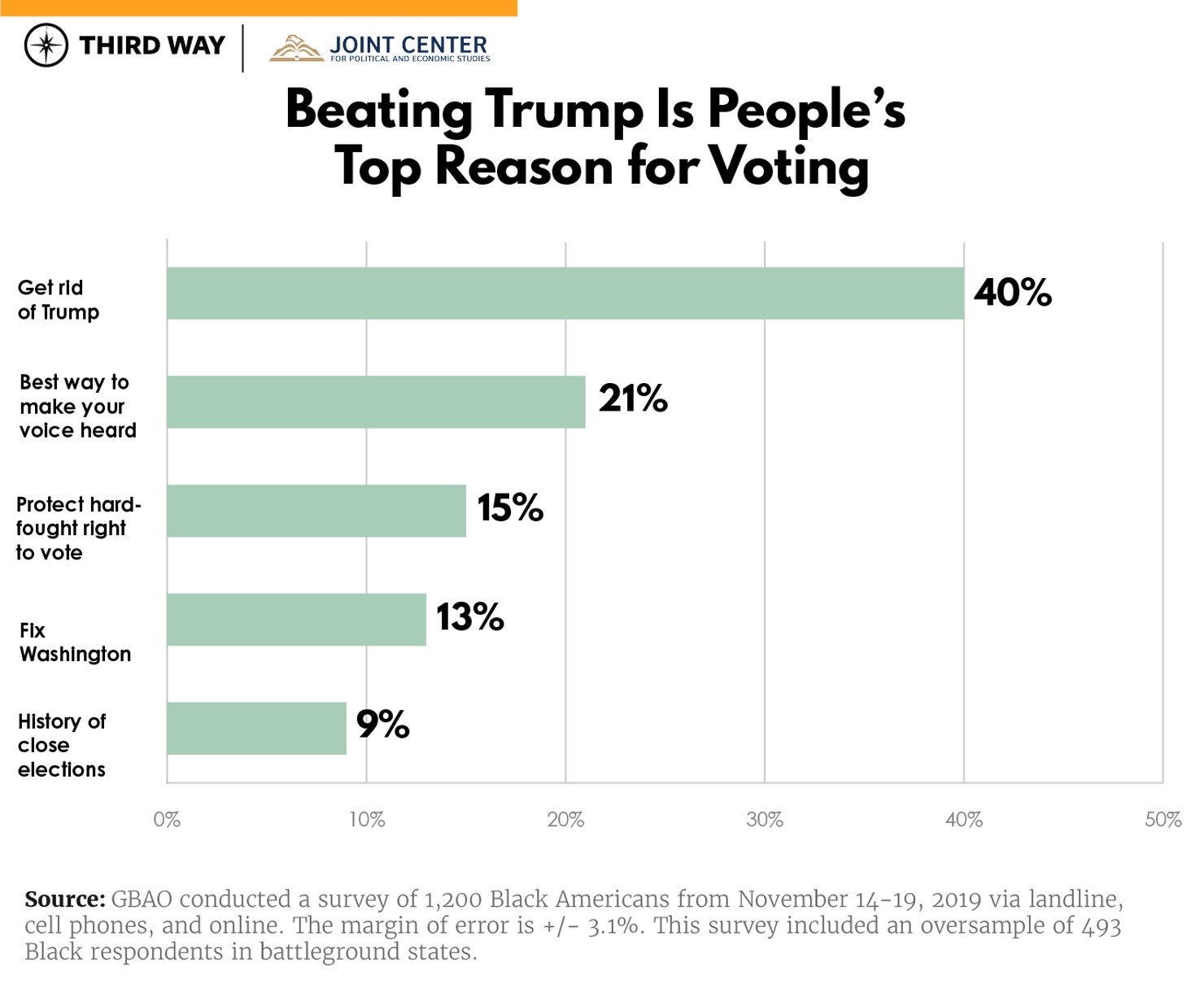

When asked the best argument to motivate them to vote, the top two reasons are throwing out Trump and that voting is the best way to make your voice heard. Just 9% cite the history of close elections as a motivator. Again, there is a significant divide by partisan self-identification on the motivation question: Those with weaker partisan leanings are 10 points less likely (39% to 49%) to be motivated by ousting Trump. Interestingly, Black people over 55 (43%) are significantly more likely to be motivated by beating Trump than those under 35 (32%).

But there is a divide by voter status on whether the Democratic Party is resonating with people and their families. By a 64–36% margin, Black voters say that Democrats in Congress understand their lives and those of their families. But non-voters say that Democrats in Congress do not understand by a three-point margin.

Priorities for Black Voters and Non-Voters

When asked about issues the federal government could address that would personally benefit their lives, our survey found that Black people across America prioritize kitchen-table economic priorities and urgent challenges threatening their neighborhoods. But the salience of issues varies among different segments of people.

This emphasis on issues that impact daily life indicated that many in the survey feel economically pinched. We asked respondents whether their financial situation had gotten better, worse, or stayed the same over the last two years. Twenty-two percent said things had gotten better, 27% said worse, and 50% said it had stayed the same. Women were 11 points more likely than men to say their situation has worsened. It is telling that so few Black Americans perceive that they have benefited during this period of relative economic prosperity in the country.

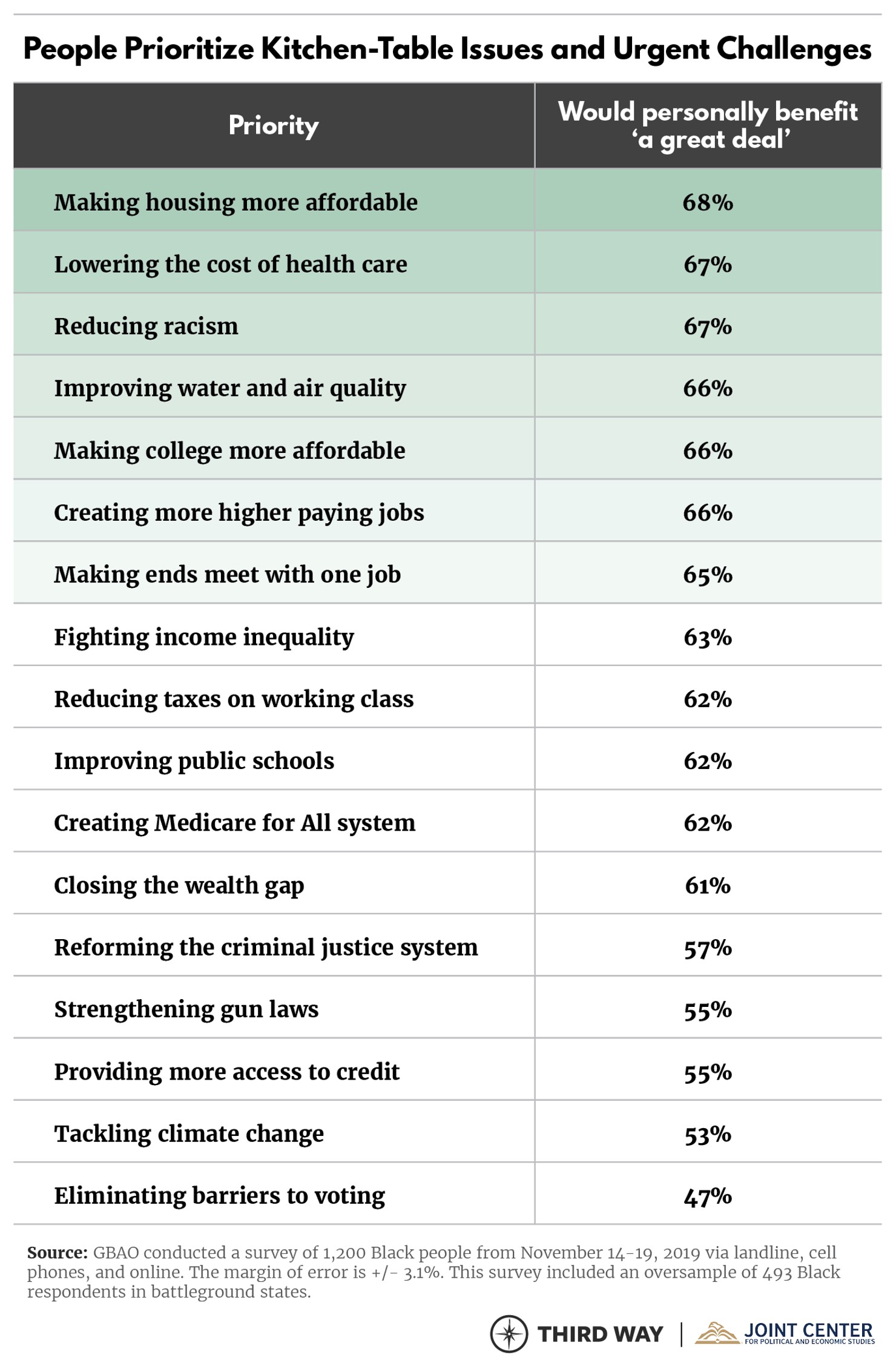

Black people have many priorities, and addressing them would make a real difference for people. Two-in-three respondents say that they would personally benefit “a great deal” from seven of the 17 priorities we tested. These include fundamental economic issues such as making housing more affordable and lowering the cost of health care, but also urgent challenges like reducing racism and improving water and air quality. This last priority was also one we frequently heard in our focus groups. The bottom of the priority list included issues, while crucially important, that some assume are the top issues for Black people, such as criminal justice reform, gun laws, and voting rights.

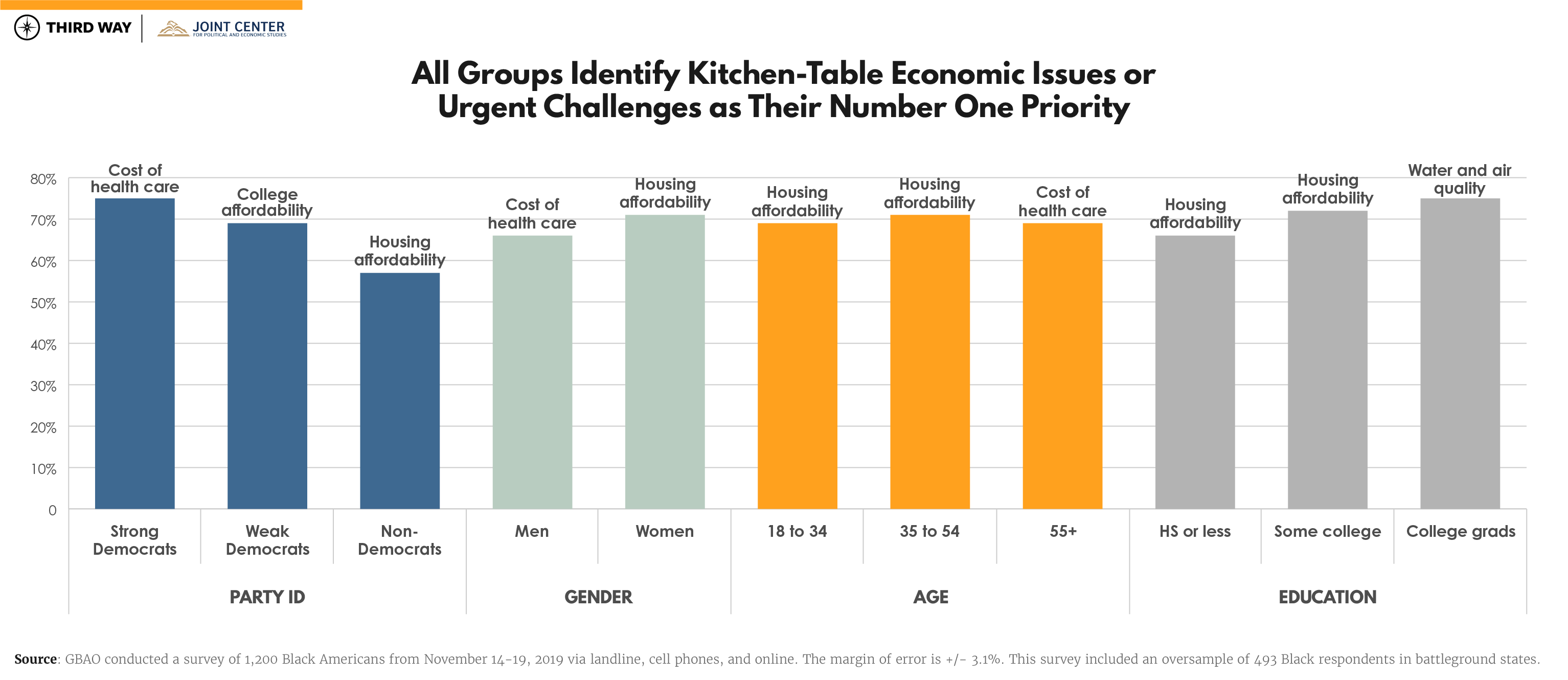

The most frequently cited top priority is housing affordability. Women, non-Democrats, those 18–34 and 35–54, and people with a high school degree or less and some college all cite it as their top priority.

Next is the cost of health care. This is the number one priority for strong Democrats, men, and those over 55.

Finally, weak Democrats say their top priority is college affordability, and college grads say air and water quality.

These top priorities reveal consistencies and distinctions among Black people, but also between them and the rest of Democrats’ coalition. Third Way’s 2019 quarterly polling of Democratic primary voters showed that these voters join with Black people in ranking the cost of health care as a top issue. But these groups diverge on other issues, such as the environment. On the environment broadly defined, primary voters prioritize action to address global climate change over improving air quality. But Black people’s priorities are reversed; improving air and water quality is near the top of their list while tackling climate change is at the bottom.

Complex Views on Race and Racism

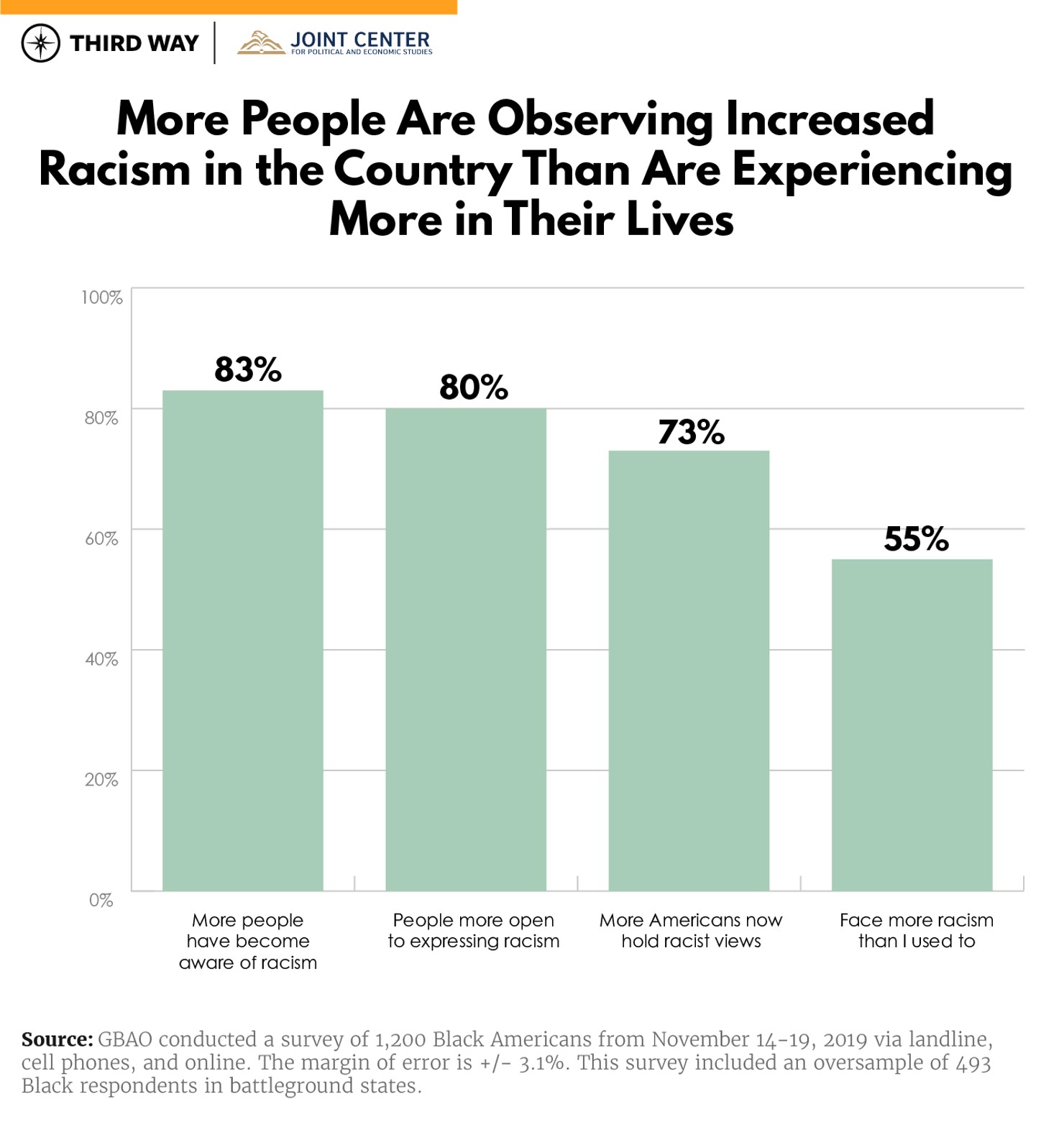

There is consensus among Black voters and non-voters that racism has come to the forefront in America today. This came through in our focus groups, where we planned for a discussion on race and racism, but participants often brought these matters up unprompted. Eighty-three percent in the survey say that more Americans are now aware of the racism that Black people experience than before Trump took office. Sizable majorities also say that more Americans hold racist views than before Trump and that Trump has made people with racist views more open to expressing them.

An even larger share of people (80%) say that Trump’s presidency has just made people with racist views more open about expressing them. In contrast to the previous question, education leads to significant differences: 91% of college grads say this is true to 72% of those with a high school degree or less.

A narrower majority at 55% say that they face more racism in their daily life than before Trump took office. This share drops further to 47% with non-voters. But whether felt personally or observed in public life and current events, the overarching sentiment from respondents across these questions is that there is more racism in America today than before Trump.

Experiences with and Perceptions of Gentrification

One of the most frequent topics of discussion in our focus groups was gentrification. It came up in nearly every group unprompted, and participants had strong feelings about gentrification – both negative and positive – and its ubiquitous discussion prompted us to dedicate a large section in the survey to it.

On balance, Black people have a narrowly negative view of gentrification. By a six-point margin, more people say it is a “bad thing” than a “good thing.” People in suburbs say gentrification is bad by a 16-point margin. But among those in cities, this margin narrows to four points. Fewer than half of people in rural areas can identify the term. Strong Democrats’ view of gentrification is more mixed than weak Democrats who have a soundly negative opinion of it. There is a potential divide by education; college grads have a strong negative view of gentrification, while those with a high school degree or less who recognize the term have a net-positive view. But fewer than half of these people know the word.

The groups more likely to cite negative effects associated with gentrification are strong Democrats and women. On cost of living going up faster than wages, 74% of strong Democrats say they are experiencing this to 64% of weak Democrats. Seventy-five percent of women say the same to 62% of men. Women are also 11 points more likely to say that small businesses nearby are closing. Those with a high school degree or less are eight points more likely than college grads to cite cost of living concerns. But they are also 12 points more likely to say that it is easier to find stores nearby now.

Splits on Ideology and Values

Some believe that because most Black people identify as Democrats, they universally align with the far-left activist base on certain core values. Our research sought to test more granular concepts to determine in what ways Black people confirm or confound these expectations.

We tested a selection of forced-choice questions that the Pew Research Center uses to build its political typology. These questions give respondents two contradictory statements and ask which one comes closest to their view. Our results show that Black people are not uniform on ideology and values, and that subgroups often come down differently on specific questions.

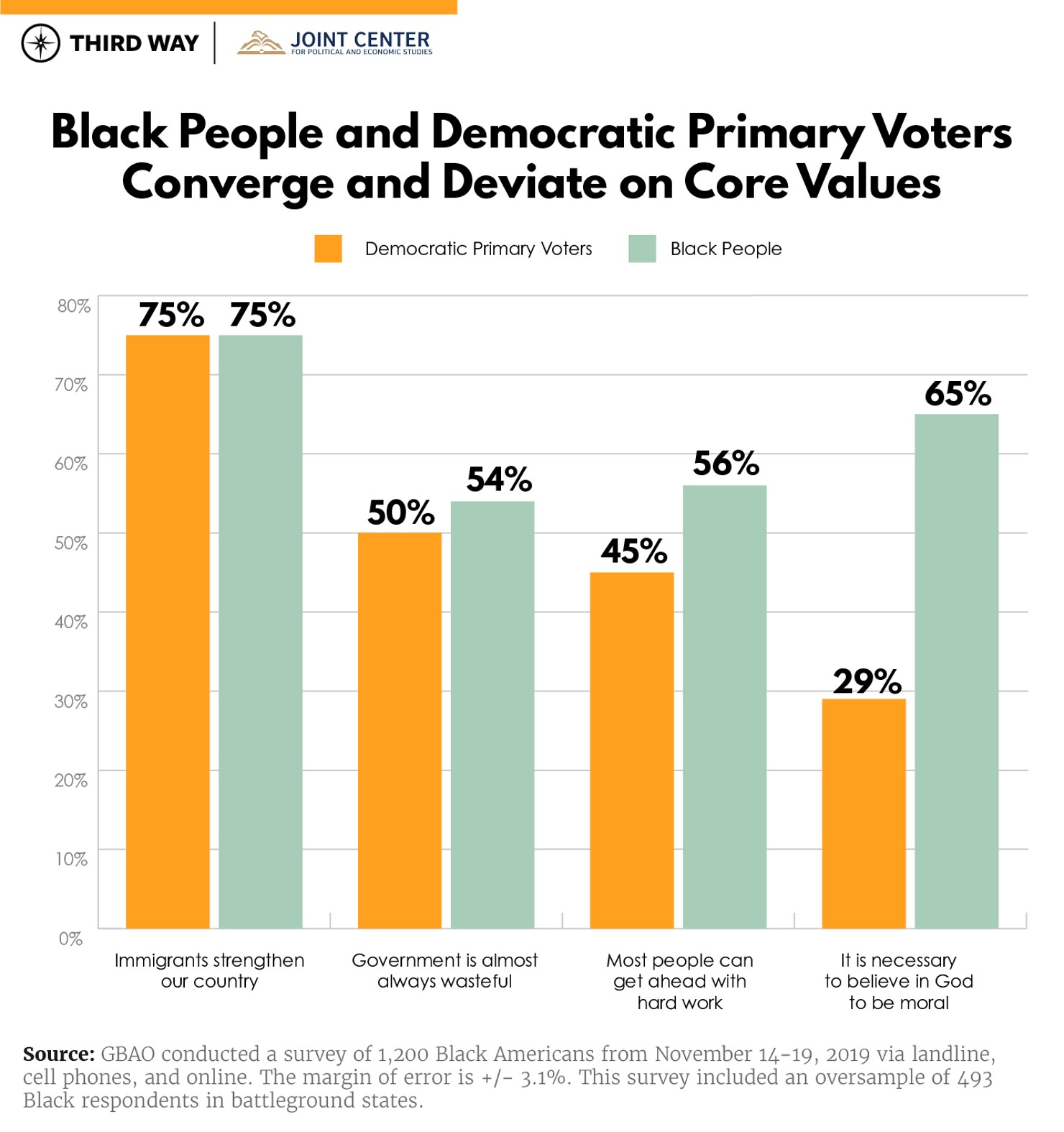

Before digging into different subgroups within this survey, it is illustrative to compare Black people overall with Democratic primary voters who were asked the same questions in a recent poll Third Way conducted with David Binder Research. Large majorities of both Black people writ large and primary voters of all races agree that immigrants strengthen our country rather than burden it. Both groups say that government is almost always wasteful and inefficient as opposed to doing a better job than people give it credit for—with Black respondents even more likely to agree than primary voters overall. But a majority of Black people say that most people can get ahead if they work hard, while a majority of primary voters say that hard work is no guarantee of success. Most starkly, on religion, these two groups are opposites. By a two-to-one margin, Black people say it is necessary to believe in God to have good morals. Primary voters of all races disagree with that statement by a comparable margin.

But the largest variance among Black people is on the question of whether believing in God is necessary to have good morals. There is a 25-point gap by age, 21 points by partisan self-identification, 15 points by education, and nine points by gender. Broadly, religion is much more intimately linked to morality with Black people than other parts of Democrats’ coalition. Still, among subgroups, there are vast differences on this issue.

Conclusion

The task for this research initiative was to better understand the attitudes, priorities, and values of Black voters and non-voters across America. Broadly, we found that Black people are politically engaged ahead of the 2020 election. One contributing factor to this is opposition to Trump, a president who most believe has ushered in more racism since he took office. They prioritize kitchen-table economic issues and urgent challenges that are threatening their neighborhoods and want policymakers and candidates to do so as well. And they are in sync with the activist Democratic base on some core values while quite divergent on others. To address the concerns of Black Americans young and old, urban, suburban, and rural, college-educated and non-college, men and women alike, we must stop painting them with a generic brush and really listen to their experiences, priorities, and values.