Blog Published March 5, 2020 · 6 minute read

American Mothers Are Dying. We Lack Basic Tools to Help Them.

Kaitlin Hunter

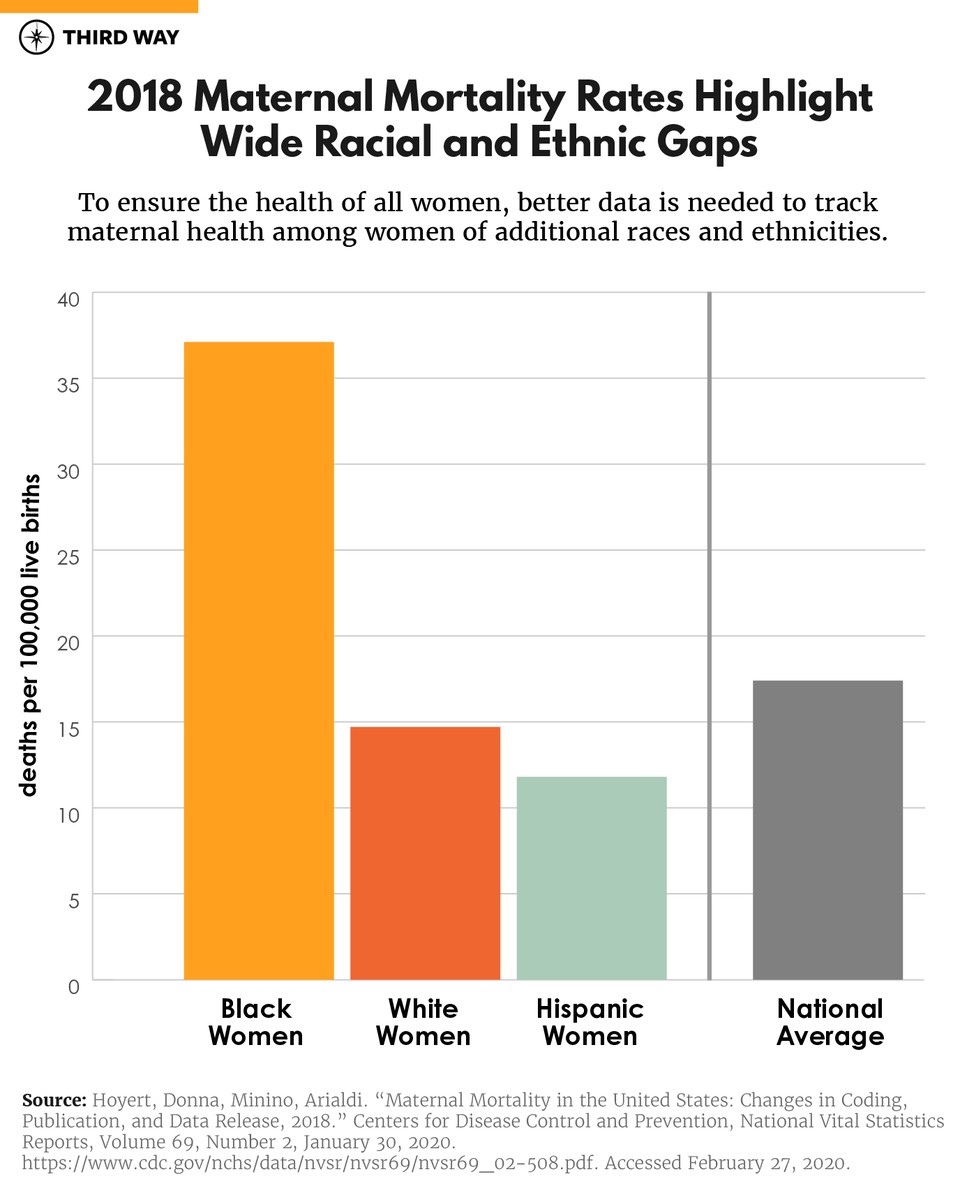

Over a decade had passed since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated a key statistic on the health of American mothers: the US maternal mortality rate. The new data is out, and it’s horrible. The CDC found that 17 mothers died for every 100,000 live babies born in 2018—that’s a total of 658 mothers lost. The United States may be one of the most advanced countries in the world, but we are in last place among wealthy nations and 55th among all countries when it comes to the health of new mothers. In our nation’s capital, those numbers are even worse. Washington, DC had an average maternal mortality rate of 33 deaths for every 100,000 live babies born. That’s higher than Syria, a country with a 50% unemployment rate that’s also in the midst of a civil war.

Breaking down the maternal mortality rate by race is even more devastating. Black women die 2.5 times more often than white women from pregnancy-related causes. That means 37 black mothers die for every 100,000 babies born. For black women in Washington DC, it’s 60 deaths per 100,000 live babies born.

This is a national crisis. But we are hamstrung in the fight against maternal mortality because the data is woefully inadequate. Not only is there a delay in getting the data, but it doesn’t show where to target financial resources. Critical populations like Native American, Alaska Native, and Asian mothers, are not included at all. Mothers over 44 years old are excluded from the national maternal mortality rate, leaving information gaps for an at-risk population and underrepresenting the national maternal mortality rate. Maternal deaths from self-harm, like suicide or overdose, are not counted in federal numbers, which means we don’t even know if this is a problem. Finally, the data only extends to a few weeks after birth. That means the 25% of mothers who have medical complications, experience violence, or are at risk for self-harm after that time are all excluded from these numbers.

Too many mothers are dying from very preventable deaths. To begin addressing this, the CDC can take simple steps to paint the full picture of this crisis. Here are three ways:

1. Maternal mortality data must include women of every race and age, including Native American, Alaska Native, Asian, and Pacific Islander mothers.

Women of color—particularly African American women—are disproportionately the victims of institutional racism. But we can’t overlook other women of color. The recent maternal mortality data only includes three categories for race: black women, white women, and Hispanic women. That excludes a lot of people. For example, Native American and Alaska Native women are more than twice as likely as white women to die from pregnancy-related problems. Furthermore, experts believe that many indigenous women are miscategorized on their death certificate, leading to an underrepresentation of maternal deaths. This is especially problematic because Native Americans and Alaska Natives have more complex problems than their white counterparts:

- More than 25% of Native American and Alaska Natives live in poverty.

- They have higher rates of unemployment.

- The have more adverse childhood experiences or childhood trauma.

- They are exposed to higher rates of physical and sexual violence in their lives.

- They have the highest prevalence of smoking and diabetes than any other racial group.

All of these factors can result in pregnancy complications. Without data that focuses on the characteristics of all women, many will continue to fall through the cracks, particularly women of color.

In addition to limitations on race data, the maternal mortality data has only counted mothers under a certain age. In the 2018 data, for example, the CDC reduced the age limit of mothers counted in the data from 54 to 44. Yet, women over 40 are seven times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than women under 25. As more women decide to have children later in life, we must measure the health of mothers of all ages.

2. Maternal mortality data must include the deaths of mothers from all causes.

The 2018 maternal mortality data didn’t include deaths related to suicide or drug overdoses, which are often linked to pregnancy and childbirth. In fact, regional studies show that as much as 14% to 30% of maternal deaths may be due to suicide or overdose. Fifteen percent of pregnant and post-partum women experience a mood disorder, and 20% of pregnant women are prescribed opioids. These factors, mixed with the lack of sleep and a major life transition like pregnancy or childbirth, could exacerbate mental illness and drug use. But, due to a lack of consistent and inclusive federal data on self-harm deaths in the pregnancy and post-pregnancy period, it’s impossible to know what needs to be done.

3. Maternal mortality data must be extended to include deaths within a year of giving birth.

The maternal mortality rate only includes deaths that occur within the first 42 days after childbirth. However, in 2018, 277 deaths occurred after that time but still within the first year of childbirth. None of those deaths were included. This exclusion underrepresents the data and masks potential patterns policymakers and researchers need to analyze how mothers are doing in the weeks and months after giving birth. In fact, research has shown that close to 25% of pregnancy-related deaths happen between 43 days and 365 days after delivery. In some states, that’s even higher. According to Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, whose National Birth Equity Collaborative is part of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, “the science is showing we really should [consider deaths] out to a year postpartum and not limit our definition to things that happen in the hospital.” Why? A study by Crear-Perry demonstrated that the leading cause of death for pregnant and postpartum women in Louisiana was homicide. It takes data to make those discoveries and to implement effective solutions.

Our nation has two gaping problems when it comes to maternal mortality: a maternal mortality crisis and a failure to collect the right data. It’s time to finally understand the extent of the problem. Congress must commit to collecting data on these gaps so we can finally address the maternal mortality crisis in this country.