Report Published November 15, 2012 · Updated November 15, 2012 · 9 minute read

China: Hu's Out; Who's In?

Mieke Eoyang, Brett McCrae, & Aki Peritz

Takeaways

This memo will address three topics:

- The transition process and China’s new leaders;

- How Chinese leadership decisions are made;

- What the leadership transition means for China…and for the U.S.

This week, the Chinese Communist Party announced the leadership team that will set the trajectory of their country for decades, replacing President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. The Party formally named the people who will lead the world’s most populous nation, direct the second-largest economy, and control the third-largest nuclear arsenal.

The Leadership Transition

The Chinese Communist Party just concluded a National Party Congress (NPC) gathering Party delegates together to “choose” their leadership. The delegates were chosen from the 80 million-member Communist Party from across China’s provinces, autonomous regions, military, and municipalities.1 This Congress has little actual decision-making authority, and serves as a rubber stamp for decisions made by others.

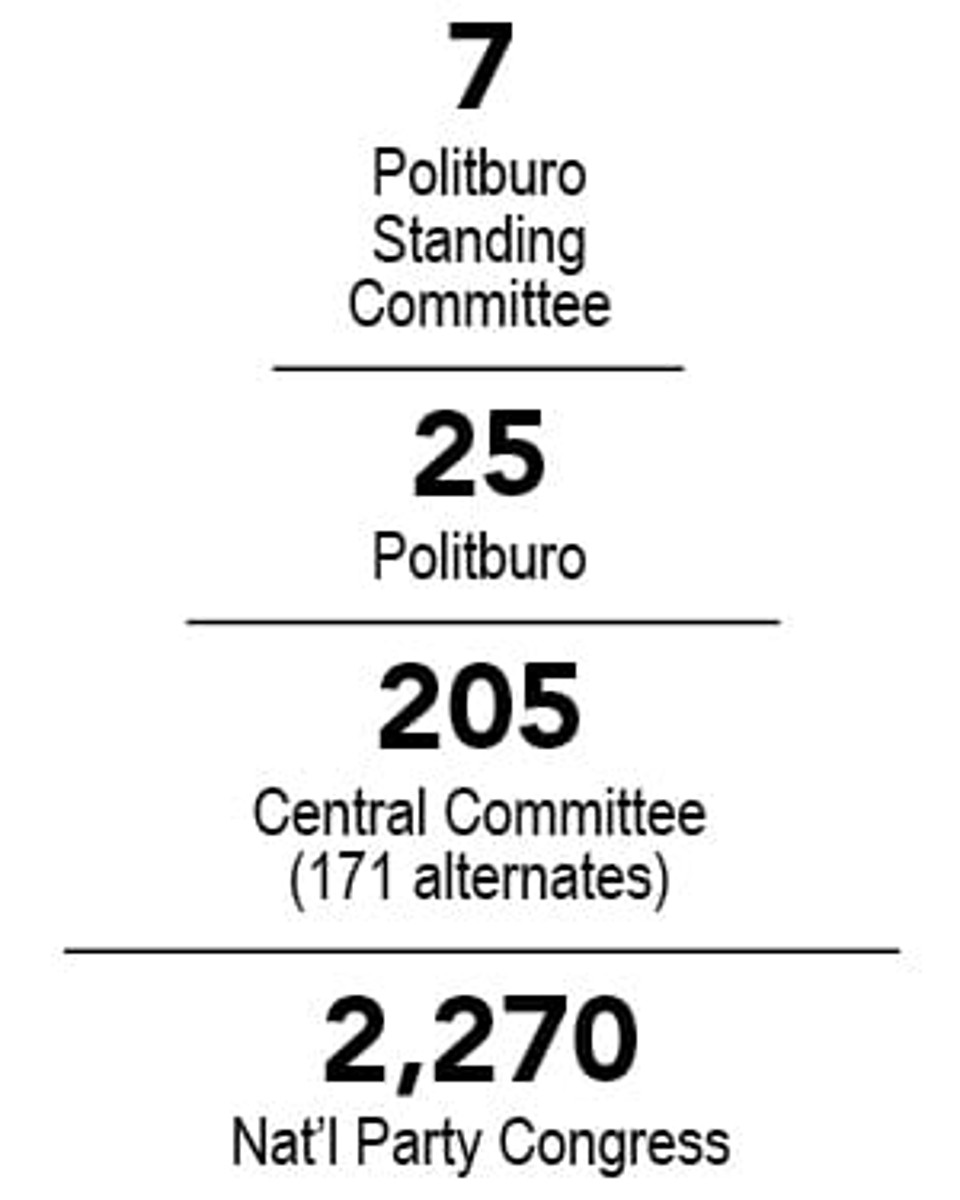

- The 2,270-member NPC selected the 205-member Central Committee, which then selected the 25-member Politburo, which selected the Politburo Standing Committee—the seven-person group that runs the Communist Party—and by extension, all of China.2

- The Standing Committee’s members will define China’s political relationship with the world for the next ten years.

The Chinese Communist Party’s National Structure3

The Incoming President and Premier

China’s leadership transition has been years in the making. Incoming President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang already served on the previous Standing Committee, theoretically providing them the experience to lead China over the next decade.

President Xi Jinping (SHEE JEEN-PEENG)4 is an engineer who spent decades climbing the Party structure in Beijing and in the provinces. He is a so-called princeling—one of the Communist Party elites’ children. Xi’s father was a former Politburo member who piloted free-market zones in China during the 1980s.5

- Some experts believe Xi generally supports free-market economics, but he also supports the large monopolistic state-owned companies, which benefits the Party.6 However, like most top Chinese officials, Xi is publicly vague on his personal stances on specific policy topics.7

- He has been married twice; his ex-wife currently lives in Great Britain. His current wife, Peng Liyuan, is a folksinger in the Army, while his daughter (from his second marriage), Xi Mingze, is an undergraduate student at Harvard University.8

Premier Li Keqiang (LEE KUH CHAHNG) oversees the day-to-day administration of the Chinese bureaucracy. He is Hu Jintao’s protégé, as the two men knew each other when Li ran the Chinese Communist Youth League during the 1980s and 1990s.9 Li also served as Party boss in various provinces and then made his way onto the Standing Committee in 2007.10

- Li is not a princeling, having risen from humble roots in a rural, hardscrabble part of China. He has been described negatively as “passive,” although U.S. diplomats have called him “engaging and well-informed."11

- Li and his wife have one daughter who reportedly studies in the U.S.12 He is the only Standing Committee member with a Ph.D in economics, and he and his wife both speak fluent English.13

Leadership Decisions

China is an authoritarian, oligarchic system based on Party membership, as well as personal and family connections. Leaders are selected by this group, from this group. This process is opaque, making it difficult to know how specific policy decisions are made, or how leaders are specifically selected.

Decision-making appears to be centralized in a small group of Party members who try to reach consensus on specific courses of action.

Chinese decision-making appears to be centralized in a small group of trusted Party members who try to reach a consensus before deciding on a specific course of action.14 This process requires extensive discussion and bargaining between individuals and organizations in order to reach an acceptable compromise to all (or most) involved.15

- The Chinese President’s influence is much more like that of the Supreme Court Chief Justice’s power than the U.S. President; while he sits atop the Party pyramid and wields great power, he can’t force the other Standing Committee members to acquiesce to his decisions.

This consensus model of governance is least effective when addressing a crisis; in such times, decisions can be long, complicated, or end in deadlock.16 For example, even after a corruption and murder scandal engulfed presumptive Standing Committee member (and Chongqing party boss) Bo Xilai earlier this year, it took the Party several weeks to remove him from political office.17

Formal titles do not indicate actual power.

Formal titles do not indicate actual power. While Americans and others call these leaders by their official titles (“President”, “Foreign Minister,” etc.), it is the Chinese policymakers’ Party position that determines their ability to make decisions.

- The last President Hu Jintao also served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee and is also the chairman of the Central Military Commission—and will remain “President” until March 2013, when he formally hands the title to Xi.18

- Throughout the last decade, State Councilor Dai Bingguo was more influential on foreign policy issues than the Foreign Minister, Yang Jiechi, because Dai was higher in the Party hierarchy than Yang.

The Party Behind the Scenes

Since the 1980s, the Party has become more market-oriented and abandoned much of its Marxist-Leninist dogma. Politically, however, China remains a one-party state and the Party’s leadership controls all major political and economic decisions.

The Party leadership controls all major political and economic decisions in China.

- The day-to-day workings of the Chinese state—China’s ministries and commissions—is controlled via the Party-controlled State Council, and most top officials in the official government are Party members.19 However, many lower to mid-level civil servants are not Party members.

- The Chinese military—called the People’s Liberation Army— is under the Party’s absolute control, as its primary mission is to keep the Party in charge.20 This is reflected in the oft-cited Mao Zedong dictum, “The Party controls the gun.”21

- The State—and hence the Party—controls or dominates vast sectors of the Chinese economy through state-owned enterprises in industries such as (but not limited to): banking, construction, petrochemicals, aviation, coal, shipping, heavy manufacturing, and telecommunications.22

What Transition Means For CHINA...

China has multiple internal problems that continually threaten to destabilize the country. Absent a foreign policy crisis, these problems will consume most the leadership’s time and attention.

China’s leaders will spend most of their time and attention on domestic challenges.

- Anger towards the government keeps rising to the surface. In 2010, there were 180,000 protests, riots, and other mass incidents countrywide—four times as many as there had been 10 years before.23

- China has a “floating” migrant population of over 200 million people—mostly rural dwellers who travel from city to city searching for work.24 This disruptive societal shift is the rough equivalent of 45 million Americans moving from city to city looking for jobs without the formal permission to do so.

- China is grappling with multiple environmental problems, such as limited water resources, air pollution, and wide-scale desertification. Beijing is trying to mitigate these problems through huge infrastructure initiatives, but enormous challenges remain. Climate change will make many of these problems substantially worse.25

- China’s economic growth may be unsustainable. China’s economy has been booming over the last few decades, but recent downward trends worry Chinese policymakers.26 A cooling off of the Chinese economy could lead to internal instability, as inequality drives resentment.27

...and What it Means for the U.S.

The U.S. and China have multiple issues in common:

- As the 1st and 2nd largest economies in the world, we are intertwined and interdependent economies. In 2011, China and the U.S. traded $539 billion worth of goods and services.28 The same year, China was the third-largest purchaser of U.S. exports, while China was America’s largest supplier of imported goods.29

- We share an interest in maintaining stability on the Korean peninsula. North Korea’s border is a short distance from many Chinese cities; a crisis involving hundreds of thousands of North Korean refugees or a political implosion in Pyongyang could overwhelm Beijing’s ability to handle such an event. And although they could do more, Beijing does not desire a nuclearized Korean peninsula, as they have supported UN sanctions against North Korea whenever Pyongyang tested an atomic device.30

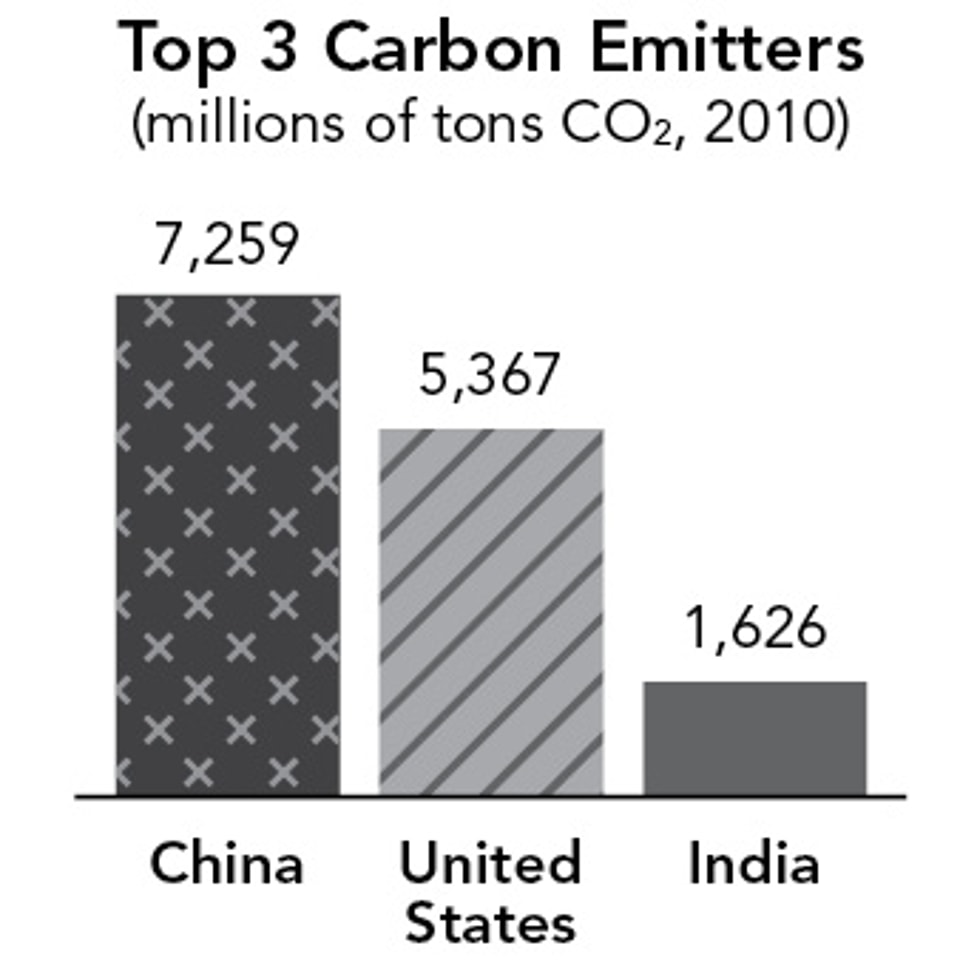

- Both countries must solve global environmental issues—together. As the world’s top oil consumers and carbon emitters, both countries share an interest in addressing the global consequences of their energy consumption.

Source: United States, Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison – Oil Consumption,” The World Factbook, November 2012. Accessed November 2, 2012. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2174rank.html; See also “CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2012,” Report, The International Energy Agency, November 2012. Accessed November 2, 2012. Available at: http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/name,4010,en.html.

Nonetheless, serious differences remain between our two nations:

- China has turned away from open markets and toward “state capitalism” in key sectors. Furthermore, Beijing employs multiple tactics to block American exports and investments, denying opportunities for our workers, manufacturers, farmers, and service providers.31

- China has a poor human rights record. According to the State Department, China continues to persecute ethnic and religious minorities, restrict political activism, enforce coercive birth-control practices, and utilize extrajudicial detention mechanisms, including detentions at unofficial holding facilities known as “black jails.”32

- China remains edgy about the Pentagon’s rebalancing to Asia. One widely-held view in China is that this move is designed to preserve American global dominance and prevent China’s rise.33

An adversarial relationship is not in Washington’s or Beijing’s interest.

Conclusion

The relationship between the U.S. and China will define the global order for the foreseeable future. How our two nations choose to address economic growth, global stability, and environmental challenges will determine the fate of the planet in the 21st century.

The U.S.-China relationship will define the global order for the foreseeable future.

To be sure, America and China have serious political differences, but how we choose to engage with each other—either in the spirit of cooperation or conflict—is of tremendous consequence. An adversarial relationship is not in Washington’s or Beijing’s interest. Understanding the new leadership in China is an important first step to building and continuing a constructive relationship between the two nations.