Report Published February 4, 2026 · 16 minute read

Families & the Tax Code: What’s Working, What’s Not

Curran McSwigan & Rory Gaudette

For decades, lawmakers have used the tax code to help America’s working families. Each policy was created with good intentions—but over time, they have piled up into a system that is hard to understand and even harder to use.

On their own, many of these tax provisions provide real support. Taken together, however, they form a confusing patchwork that limits their impact. As policymakers consider how to strengthen support for working families, they need a clearer picture of how this system actually works. In this report, we examine the six most significant tax policies that support working families:

- Child Tax Credit

- Credit for Other Dependents

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit

- Dependent Care Assistance Program

- Employer Provided Child Care Credit

We explore how each policy works as well as legislative updates, program concerns, and key policy considerations. We also highlight four important interactions between tax policies that reduce the impact for the families they are meant to benefit.

1. Child Tax Credit

The federal Child Tax Credit (CTC) was enacted in the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 with the goal of alleviating some of the financial burden experienced by working families with children. The federal CTC has undergone many revisions, both temporary and permanent, over the years. While the CTC continues to provide meaningful assistance to America’s working families, it falls short for the poorest families, who are not able to get the full value.

How It Works

The CTC reduces a filers’ federal income tax by up to $2,200 per qualifying child. If no federal income taxes are owed, the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC) provides some households the partial value of the tax credit as a tax refund. Though technically separate, the CTC and the ACTC are calculated together during tax filing.

Total credit eligibility and value are determined by household income and size.1Families must earn at least $2,500 to receive any amount of credit, creating a de facto work requirement.2The CTC phases in at a rate of 15 cents for every $1 earned above $2,500. For every dollar a single filer earns over $200,000 or joint filers earn over $400,000, the credit declines by $0.05.3For households whose federal income tax burden is less than their CTC benefit, the ACTC refunds 15% of filers’ earnings above $2,500, up to a maximum refund of $1,700 per child.

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)

OBBBA permanently increased the maximum credit to $2,200 per qualifying child and mandated automatic adjustments for inflation in future years.4OBBBA requires the taxpayer (or, in the case of a joint return, one of the spouses) and the children claimed both to have a Social Security Number in order to receive the Child Tax Credit; previously, only claimed dependents were required to have an SSN.5

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- Too little support for low-income children: In 2021, the American Rescue Plan temporarily increased the CTC’s value, eliminated the earnings requirement on families, and created full refundability, allowing families to receive the full credit even if they did not have a tax burden.6This expansion was a huge middle- and working-class tax cut and lifted 2.1 million children out of poverty.7Since the expanded benefits expired in 2022, the CTC today creates the smallest net benefit for families with lower incomes.8Future changes to the CTC should allow a more rapid phase-in of benefits or an increase in refundability.

- Credit value should remain tied to inflation: Tying the CTC to inflation is one of the most significant changes made by OBBBA, as it prevents the credit value from eroding over time. It is imperative that this link not be undone by future legislation.

- Eligibility changes continue to hurt families in need: Modifications to eligibility requirements exacerbate the existing obstacles that families face in accessing the credit. These barriers to uptake include a lack of awareness of the credit due to limited IRS outreach, lack of interaction with the tax system by low-income households, and extra steps required for households without recent returns to file for the credit.9Families who have low enough incomes aren’t required to file tax returns. When the CTC was expanded under the American Rescue Plan, the IRS found it difficult to ensure low-income families understood that they needed to file a return anyway in order to receive the credit.10Changes to CTC eligibility can create confusion among families. Clear communication from benefits agencies is essential to maximizing uptake, especially for lower-income families that may not habitually file tax returns.11

State Child Tax Credits

While the first state CTC was introduced by New York in 2006, most state-level CTCs were enacted or significantly expanded following the temporary boost to the federal CTC in 2021. These credits are a powerful tool for states to supplement the federal credit and further reduce child poverty.

How It Works

Fifteen states and the District of Columbia offer their own CTC, 11 of which are fully refundable.12State CTCs vary in credit amounts, age eligibility, and refundability, with the lowest being a $100 non-refundable credit per child in Arizona and the highest a $1,800 refundable credit per child in Minnesota.13Many states link their programs to the federal CTC by mirroring federal eligibility rules or setting their credit values as a percentage of the federal credit.14

2. Credit for Other Dependents

The Credit for Other Dependents (ODC) was enacted as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, providing families with older dependents a smaller tax benefit. The driving force behind providing this benefit, in addition to beefing up the CTC, was changes under TCJA that eliminated personal and dependent tax exemptions. However, the ODC benefit is $500, while previous dependent exemptions capped out at $4,050. These changes created a drop in tax relief for many families with children.15

How It Works

The ODC provides up to $500 in non-refundable tax relief for each dependent who does not qualify for the federal CTC. Eligible dependents include children ages 17 and 18, full-time students ages 19 to 23, and older dependents with disabilities.16If a filer owes less than $500 in federal taxes, they will not receive the full benefit.17Additionally, this credit is not tied to inflation.

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The ODC was set to expire in 2025, but OBBBA made it permanent.18

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- Poor substitute for more robust CTC: Currently, one of four families with “other dependents” are partially or entirely ineligible for the credit due to their household income being too low.19Families caring for dependents with disabilities are more likely to have reduced earnings because of the time required to provide care. As a result, many of the households targeted to benefit from the ODC are likely to be excluded because eligibility requires recipients to have a tax burden above $500. Plus, ODC’s much smaller value—and the fact that its value continues to be eroded by inflation—means it may not provide meaningful assistance for caretakers.

3. Earned Income Tax Credit

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was introduced in 1975 to provide financial aid to working families with low to moderate incomes.20Designed to offset income and payroll taxes, the credit incentivizes work by boosting take-home pay.21The refundability of the EITC makes it an efficient anti-poverty policy tool, though childless workers are largely left unassisted in its current structure.

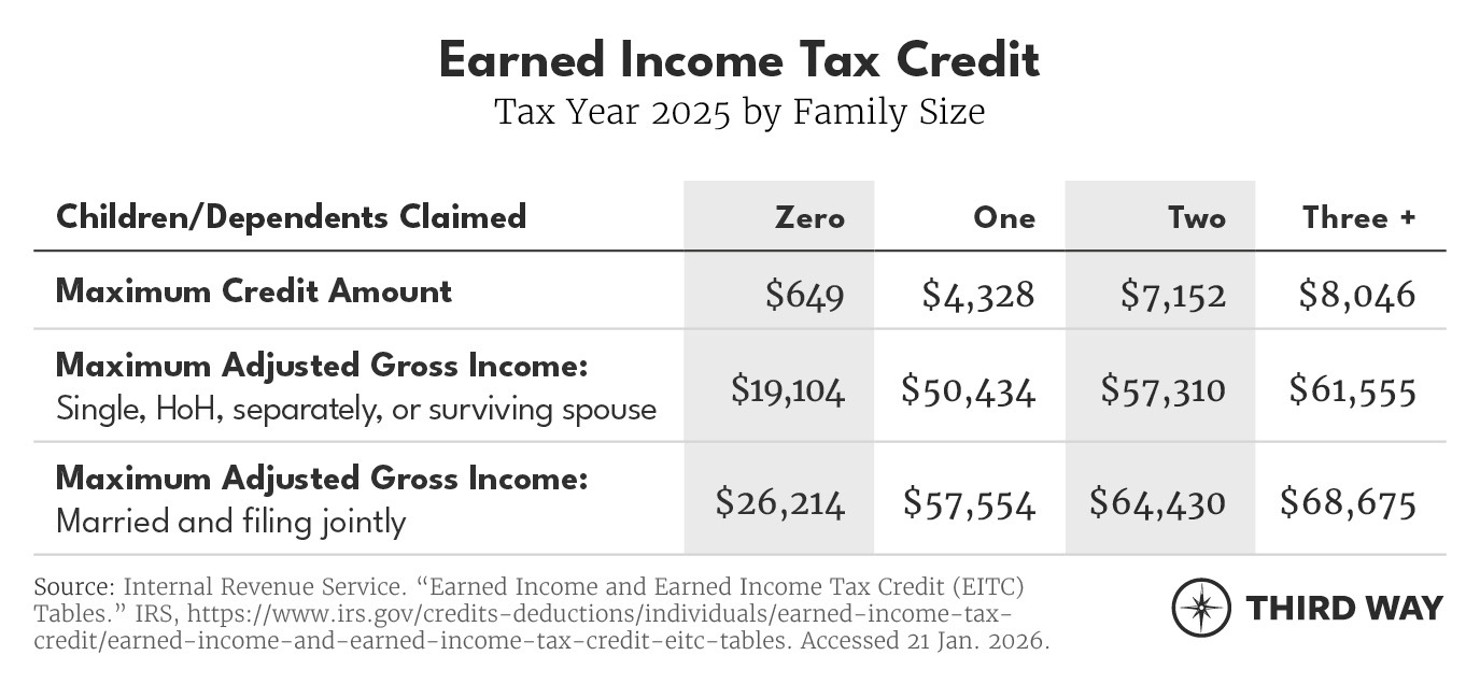

How It Works

The EITC provides a refundable tax credit to working families, with benefit amounts determined by household earnings and family size. The EITC phases in as earnings increase, plateaus, and then phases out at higher levels of income. A family with two children must have an income of at least $17,880 to receive the maximum credit.22The same family will no longer receive any credit when their jointly-reported income exceeds $64,430.23While not explicitly a family tax credit, childless workers must be between ages 25 to 64 to be eligible, a criterion that does not apply to workers with children.24Additionally, childless workers typically receive smaller credits when eligible. Today, 97% of EITC benefits currently go to families with children.25

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

OBBBA did not amend the EITC in any meaningful way.

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- Administrative hurdles are a barrier to uptake: Only about 80% of eligible families claim the EITC.26They may be dissuaded by complexities in the application process, burdens associated with gathering the required documentation, or lack of awareness about the credit itself.27

- Navigation issues drive improper payments: The EITC continues to see high levels of improper payments, which are defined as payments that should not have been made or were made in the wrong amount.28In 2023, 33.5% of payments were estimated to be improper, to the tune of $22 billion.29There is broad consensus among researchers that improper payments can largely be attributed to unintentional errors by filers, typically because of mistakes around income reporting or child eligibility.30The erosion of funding for IRS enforcement in recent years further constrains the agency’s ability to prevent these invalid payments.Simplifying eligibility requirements and bolstering the IRS’s ability to authenticate filers’ eligibility would aid in reducing this high error rate.31Filers claiming the EITC are found to be audited at a rate four times higher than that of all individual income tax returns, in part due to ongoing error issues with the program.32But audits are also shown to dissuade people from claiming the EITC the following year, meaning that addressing the root issue of eligibility confusion can improve credit uptake and retention.

4. Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit

The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) was first passed in 1976 as a tool to assist working families with the costs of child care. By offsetting a portion of work-related child care expenses, the CDCTC plays a crucial role in assisting families, particularly those with two working parents.

How It Works

The CDCTC allows taxpayers to claim a portion of the dependent care expenses they incur while working or seeking employment as a non-refundable tax credit.33Eligible dependents include children under the age of 13 and dependents who are unable to care for themselves. The value of the CDCTC is calculated by multiplying qualifying expenses by a rate that varies with household income, from 50% for households earning less than $15,000 to 20% when household income exceeds $103,000 for single filers and $206,000 for joint filers.34The CDCTC applies to expenses up to $3,000 for one qualifying dependent and $6,000 for two or more.35

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

OBBBA boosted the credit rate for families with an annual income of less than $15,000 from 35% to 50%. This means that the maximum credit for one qualifying dependent increased from $600 to $1,050, and the maximum credit for two or more qualifying dependents increased from $1,200 to $2,100.36Again, this credit is only meaningful if the caregiver has income tax liability.

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- Low-income families receive less benefit: The CDCTC has provided significant financial relief to working parents, with over 5.7 million families benefiting from the credit in 2022.37While the credit rate is highest for lower-income households, many of these households do not receive the full value of the benefit because the credit is not refundable.38

- Value isn’t keeping pace with rising costs: The $3,000 cap on eligible expenses per child falls far short of what families actually spend on child care each year, and its value continues to erode because it does not adjust for inflation.39The credit value has not increased in value since reforms were implemented in 2001.40If the value had been tied to inflation, it would be worth $5,500 in 2026.41

5. Dependent Care Assistance Program

The Dependent Care Assistance Program (DCAP) was established in 1981 as a tool to help reduce child care expenses for working parents. While the previous tax policies supported families by reducing their end-of-year tax burden, this benefit works by excluding earnings used for eligible expenses from taxable income. Though recently updated, the benefit still fails to keep up with the spiraling costs of child care.

How It Works

An employer’s DCAP allows employees to set aside a portion of their wages on a pre-tax basis to pay for qualifying dependent care expenses. Eligible dependents are defined as children under the age of 13, or dependents who are incapable of caring for themselves and who lived with the employee for more than half of the year.42The expense amounts are elected through payroll deduction and are excluded from the employee’s taxable income. Employers may also contribute to an employee’s DCAP account; those contributions are also excluded from income taxation.43By reducing taxable income and allowing families to pay for child care with pre-tax dollars, DCAPs help lower employees’ overall tax burden and offset some dependent care costs.44There is no set limit on an eligible employee’s income, but there is a limit on how much they contribute tax-free (currently $7,500).

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

OBBBA included the first permanent expansion to DCAP in the program’s history, increasing the annual employee contribution limit from $5,000 to $7,500.

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- Program structure means certain families benefit more than others: Under the current system, annual DCAP funds not used by a family after the 2 ½ month grace period are lost.45Because many DCAP plans require contributions to be committed before the beginning of the year, parents may allocate more funds than they need, and families with variable child care needs can find themselves worse off after losing these dollars. Additionally, because the benefit lowers taxable income, the program provides greater benefit to high-earning employees at higher marginal tax rates.

- Contributions not keeping pace with cost: DCAP contribution limits have failed to keep up with the skyrocketing cost of child care, even with the recent expansion under OBBBA. When introduced in 1981, the contribution cap was $5,000, and average annual child care costs for families were less than half of this limit.46Today, annual child care costs are more than double the newly updated $7,500 limit.47By not tying contribution limits to actual child care costs, DCAP provides less support for families today than when first introduced.

6. Employer-Provided Child Care Credit

The Employer-Provided Child Care Credit, also known as 45F, was introduced on a temporary basis in 2001 and made permanent in 2012 by the American Taxpayer Relief Act. The credit takes a unique approach to the problem of child care costs by incentivizing businesses to provide child care options for their employees. Recent expansions and modifications to the credit through OBBBA seek to boost the low rate of credit uptake by employers.

How It Works

The 45F credit provides a non-refundable tax credit to employers for qualifying child care expenditures and referral services.48Qualifying expenditures include the costs associated with acquiring or operating a child care facility, contracting with third-party care providers, and providing referral services for finding care.

Changes From The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

OBBBA increased the maximum 45F credit from $150,000 to $500,000 per business ($600,000 for small businesses) and increased the maximum credit rate for child care expenditures from 25% to 40% (50% for small businesses).49The law also allows small businesses to jointly operate child care facilities and introduces annual inflation adjustments to the maximum credits.50

Policy Concerns and Recommendations

- A history of low uptake: Prior to OBBBA reforms, many employers did not see 45F’s incentives as enough to justify an investment in child care services.51OBBBA’s expansions attempt to address this by increasing the maximum credit allowed and providing additional benefits to small businesses.52These improvements reflect bipartisan provisions included in Senator Tim Kaine (D-VA) and Senator Katie Britt’s (R-AL) Child Care Availability and Affordability Act, introduced in 2025. The legislative text in the bill served as a blueprint for OBBBA’s 45F reforms.

- Excludes certain business types: The credit’s non-refundability means that 45F provides no incentive to businesses that don’t owe income or corporate taxes, such as those not making a profit.53This can be a concern when it comes to non-profit organizations, some hospitals, or schools.

Policy Interaction and Overlap Challenges

Despite the value of the programs outlined above, working families face a patchwork of overlapping benefits, each with their own limitations and obligations.54Differences in eligibility requirements make it difficult for families, particularly those with fluctuations in income and caregiving arrangements, to receive the full benefits they are allotted. Here are four areas ripe for reform:

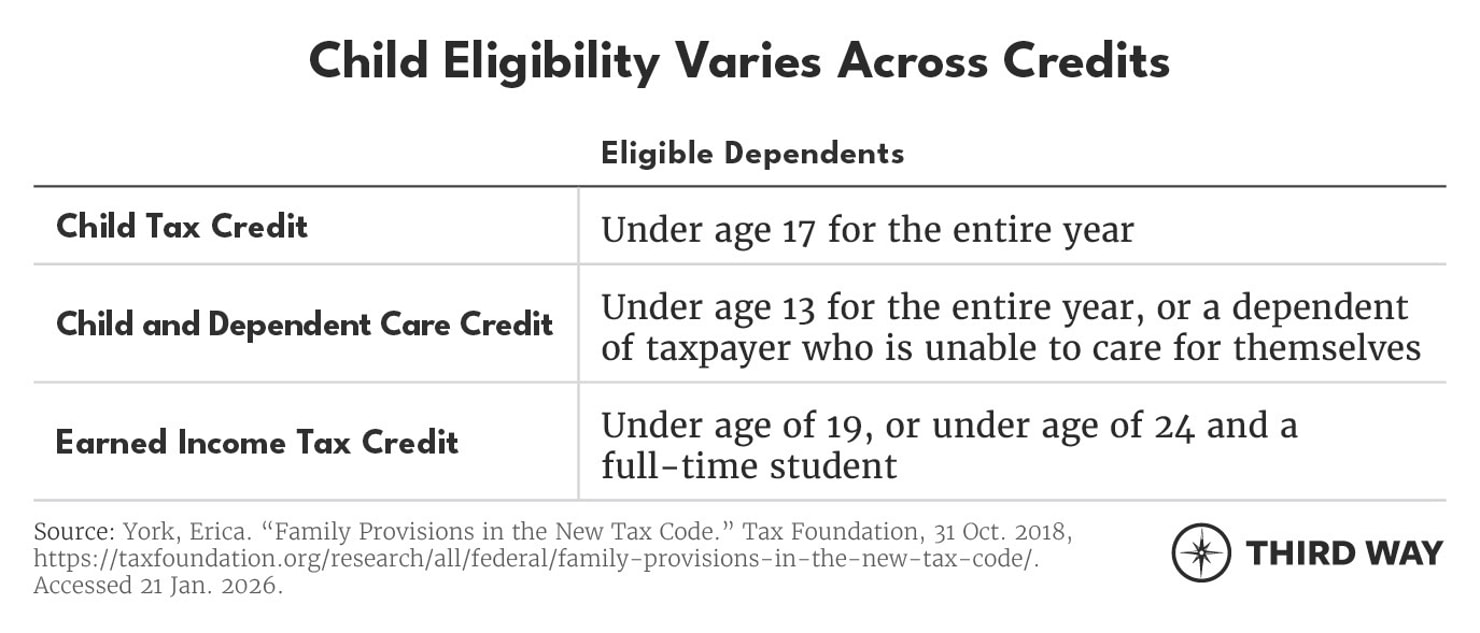

1. Conflicting definitions and rules: The CTC, CDCTC, and EITC all support families with children by alleviating some of their tax burden. Despite sharing a desired outcome, these credits diverge when defining age-thresholds for children, which parent can claim the child, and how the child’s living arrangement may impact eligibility.55These inconsistencies may confuse and dissuade eligible taxpayers from claiming credits they are entitled to.

2. The potential redundancy of CTC and EITC: The CTC and EITC combine to create a powerful anti-poverty mechanism, helping millions of families afford basic necessities.56With both credits centered around the household’s number of children, there is significant overlap between the two. This creates redundancy and leaves groups like childless workers and low-income single filers with little support. A less redundant and more equitable system might provide two distinct credits that separately target child expenses and wage support.57

3. The single claimant problem for child credits: As household structures evolve, with cohabitation and divorces increasingly common, tax benefits for families have failed to keep up. A child can only be claimed by one person for the child-related credits (EITC, CDCTC, CTC); taxpayers are unable to claim a child for some benefits and allow another caretaker to claim the same child for others.58As more families experience dynamic caregiving situations, tax benefits will increasingly leave behind families that fall outside of the married household norm.59

4. DCAP affecting CDCTC eligibility: When families use DCAP alongside the CDCTC, the two benefits can unintentionally work against each other. Under current law, any employer-provided DCAP contributions must be subtracted from the maximum amount of child care expenses a taxpayer can claim for the CDCTC. This means that families who receive substantial DCAP benefits may see their CDCTC eligibility reduced or eliminated entirely.60For example, say a parent with one child who receives $10,000 in DCAP assistance from their employer. Since the CDCTC maximum is $3,000 per child, and the parent received more than that maximum from their employer in DCAP assistance, that means the parent is unable to claim the credit.61The interaction between these two provisions penalizes working families who want to take advantage of employer-sponsored child care benefits.

Conclusion

Working- and middle-class families benefit greatly from the tax policies discussed above. Some are key parts of our country’s infrastructure to support low-income workers, while others help subsidize the cost of caring for loved ones. But unique eligibility requirements and payout structures create a confusing system that families must navigate to obtain the benefits they are entitled to. And while recent reforms under OBBBA created some stability through permanent extensions, benefit increases, and inflation indexing, the law also burdened families with new eligibility requirements and a large increase in the national debt. As policymakers continue to look to the tax code to support families, they must ensure they are capturing the needs of families and ensuring that their policies have the intended effect.