Report Published January 21, 2026 · 21 minute read

Progress on Paid Leave: Lessons from the States

Olivia Newman & Curran McSwigan

Two decades ago, California became the first state to establish a state-level paid leave program for workers. Fast forward to today—12 additional states, plus Washington, DC, have followed suit with their own comprehensive paid family leave programs. Other states are also expanding paid leave options through a slew of initiatives.

Yet, while states continue to make progress on paid leave, federal momentum is limited. One of the most significant steps in recent years was the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act (FEPLA), passed over five years ago to guarantee federal workers 12 weeks of paid parental leave. But progress since then has been minimal. Even with the House Bipartisan Paid Family Leave Working Group introducing legislation earlier this year to expand paid leave to more Americans, the overall issue remains stalled in our current political environment.

It’s time for federal policymakers to get off the sidelines and prioritize progress on paid leave. As they do so, there are good lessons to be learned from the states. In the report below, we highlight the three different types of paid leave programs states are utilizing, main takeaways for federal policymakers, and considerations for federal paid leave legislation.

Program Types

Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML) provides workers with paid time off for specific family and health-related circumstances, such as welcoming a new child, experiencing a serious medical condition, or caring for a loved one who is ill or injured.1 A little over half of US employees are eligible for 12 weeks of unpaid leave through the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), but many cannot afford to miss multiple paychecks. Employees with PFML benefits receive a portion of their regular salary while they are on leave, helping them to care for themselves or their families without sacrificing their financial security.

In the absence of a federal PFML policy, some states have stepped in to provide workers with PFML. (For more in-depth details on state offerings and PFML as a whole, see the Bipartisan Policy Center’s table here.)

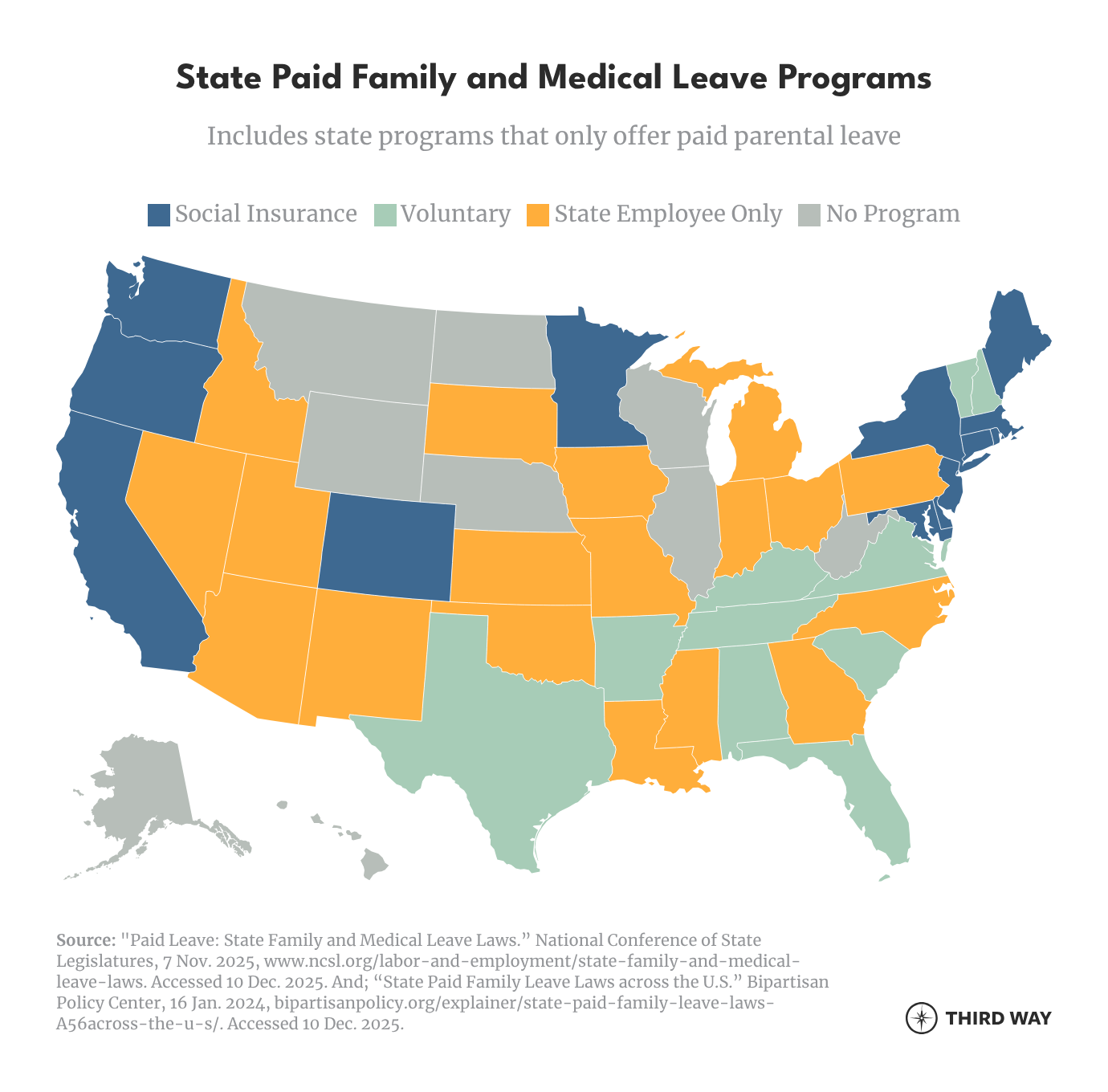

Because states set their own PFML policies, each is unique. Still, most PFML programs fall into one of three categories: social insurance, voluntary, or state employee-only. Currently, 13 states and DC have social insurance programs, 12 states have voluntary programs, and 19 states have state employee-only programs. Below we briefly define the key features of each program type.

Social Insurance Programs

The share of states with social insurance programs—where dedicated payroll deductions from employees and/or employers are redirected to a state-managed fund that finances PFML benefits—has grown significantly in recent years.2 Of the 13 states with social insurance programs, New York is the only one that requires employers to purchase PFML plans from a private insurance market and doesn’t utilize a state-managed fund.3

Social insurance paid leave programs require most private employers to enroll while exempting certain public employers, such as local government agencies or school districts.4 Exempt employers can normally opt in, as can many self-employed workers and independent contractors.5 Of these state programs, some have been in effect for decades, while others were only recently enacted.6

Voluntary Programs

States with voluntary programs allow most private employers and non-covered individual workers to purchase PFML plans from private insurance companies on an optional basis.7 As with the social insurance plans, payroll deductions from participating employers and/or employees fund the benefits.8 Most voluntary programs are relatively new, having only been implemented within the last five years.9 Some state governments help facilitate their voluntary programs by contracting with a single insurance provider that offers PFML plans for all the state’s eligible employers.10 The majority of voluntary states, however, permit multiple insurance companies to sell PFML policies so that employers and workers can choose their provider. As a result, unlike social insurance programs, most voluntary PFML benefits are managed entirely by the insurance companies selling the plans.11

State Employee-Only Programs

Other states offer paid leave programs only for state employees, such as government agency workers or teachers.12

Some of these states provide employees with full PFML, which usually covers medical caregiving for oneself or one’s family members, parenting a new child, and handling a family member’s military deployment. Other states offer only paid parental leave (PPL).13 These programs are somewhat new, with the earliest being implemented in 2017.

We categorize each state based on their PFML program type in the map below.

Four Takeaways from State Programs

Thanks to states implementing and collecting data on their PFML programs, several patterns have emerged. Below, we break these trends down into four key takeaways lawmakers can use to craft accessible PFML policies that encourage benefit usage by workers.

1. Robust benefits and marketing increase PFML use.

More people take advantage of PFML in states that offer robust programs and effectively advertise their benefits. Programs with progressive wage replacement rates—where low-wage workers receive a larger percentage of their income during leave than higher-wage workers—can also help make programs affordable, both for states to offer and workers to use.14

Fewer employees will take advantage of a PFML policy if wage replacement rates are too low. Workers earning smaller incomes often find it too hard to take a 30% or 40% cut in pay, even in the short-term.15 A sliding scale approach ensures that workers at all incomes can afford to take leave. In California, employees received between 60% and 70% (depending on income) of their normal weekly wages up until 2022.16 Then, California raised the wage replacement rate so that workers received between 70% and 90% of their earnings.17 After this increase, PFML applications rose by about 16%.18 At the same time, New Jersey found that its flat 66% wage replacement rate was actually disincentivizing some workers—particularly fathers—from using paid leave.19

More generous PFML policies also include longer durations of leave. Programs normally cover employee absences lasting anywhere from six to 26 weeks, with employees more likely to take advantage of programs that allow longer leaves.20 When New Jersey expanded its PFML program by increasing the maximum leave time from six to 12 weeks and boosted the wage replacement rate, the number of PFML claimants in the state rose sharply.21 Similarly, Washington, DC bumped its maximum leave to 12 weeks in 2022, which likely contributed to the uptick in demand in the following year.22

Additionally, more employees use PFML when states advertise benefits and help workers understand how to use them. In New Jersey and Washington, DC, state government agencies worked to make more employees aware of the benefits available to them. In New Jersey, several state agencies collaborated to develop the Maternity Coverage Timeline Tool, which allows parents to estimate the dates PFML benefits will cover.23 In DC, the Department of Employment Services utilizes social media, webinars, and partnerships with local businesses to share benefit information with eligible workers.24 In both states, these awareness efforts were found to be an important driver of increased PFML uptake—meaning eligible workers were using the benefits at higher rates.25

2. States are on different timelines—which creates varying needs.

Most states with voluntary PFML programs established benefits within the last five years, whereas states with social insurance programs have a mix of decades-old initiatives and more recent policies.26 As a result, state programs are in various stages of development and need different types of federal support depending on where they are in the process.

California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island’s PFML programs are all over a decade old, making them some of the oldest paid leave initiatives in the nation.27 These established state programs have had time to build up their funding pools, increase program awareness and understanding, and adjust their regulations based on years-long observations of workers’ needs. Unsurprisingly, PFML usage has increased each year since the program’s implementation in all three states.28 However, lower-income employees are still disproportionately excluded from accessing PFML benefits, as many are ineligible based on their job type or lack of work history.29 These states with longer-tenured social insurance programs still see places where federal support could expand the reach and impact of benefits.

PFML benefit usage has also grown over time in states with newer social insurance programs, but they typically see lower participation compared to those that are decades-old.30 Some states with new systems are struggling to get their new programs off the ground at all.31 These states are often still acquiring start-up funding, raising awareness about the benefits, and getting employers and workers acclimated to PFML—all of which likely slow their progress.32 States with new social insurance programs need federal support to get their programs up and running faster so that more workers can start taking advantage of PFML benefits.

Most voluntary programs are also new and have few participants. In both New Hampshire and Vermont, for example, only a small percentage of the eligible private workforce—1.6% in New Hampshire and 0.7% in Vermont—pays into the state’s PFML program.33 Unlike social insurance programs, low participation in voluntary PFML programs is likely due to the cost for employers and workers.34 Voluntary programs tend to be more expensive because workers who choose to enroll in PFML are more likely to need the time off.35 By requiring participation, social insurance programs have way more people paying into the fund than utilizing it in a given year. This keeps costs lower as insurance companies know utilization will likely remain consistent year-to-year. But, under voluntary programs, there is a level of self-selection where people who need it are more likely to enroll. To keep up with the demand for leave, administrators increase the cost of participation.36 These higher payments may deter employers from purchasing a group plan, especially because employers often share the cost of PFML with their employees. While employers in some states can choose to offer PFML and pass the entire program cost onto their workers, these employees may opt out of a group plan due to the high costs.37 States with voluntary programs need federal support to lower the financial barriers for both employers and employees to participate.

3. Issues persist when it comes to data and small business.

Under voluntary programs, there is no obligation for insurance providers to offer PFML, report how many employers have purchased a plan, or track the number of workers enrolling and taking leave. As a result, there is no way to know whether PFML benefits are actually reaching eligible employees.38 This lack of data makes it challenging to track the effectiveness of PFML initiatives, especially in voluntary program states. For example, in Texas, where employers can purchase PFML coverage from private insurance companies, only two providers currently offer PFML plans; neither has disclosed how many employers are enrolled.39

Because individual states control whether and how to provide these benefits and report uptake, comparing program data across states is difficult.40 This makes it hard for researchers to determine which policies most effectively encourage uptake, reach low-to-middle income workers, and achieve other measures of success.

Although PFML can be advantageous for employers of all sizes, right now, only about half of small businesses in the United States provide their employees with any paid family or medical leave.41 With small business employees making up around 46% of the private workforce, this leaves a significant number of workers with less access to benefits than those at larger companies.42 Currently, some states with social insurance programs provide certain exemptions or carveouts for small businesses. This may mean exempting small businesses from paying any sort of premium for their employees’ participation or from providing the benefits altogether.43

Often, small employers that opt out of PFML cannot afford to provide the benefits, even if they would like to offer them. New Jersey, for example, saw pushback when legislators floated the idea of reducing their current PFML exemption for small businesses. Currently, businesses with less than 30 employees are exempt from providing the state-mandated 12 weeks of job-protected paid leave, but policymakers sought to drop that to just businesses with less than five workers.44 Some smaller organizations said that they were not financially equipped to cover an increase in employee absences or the cost of hiring temporary workers.45 These concerns are a significant barrier to small businesses owners offering paid leave; studies show that eight-in-10 small business owners would like to provide more PFML than their company can currently afford.46 But for many of these small employers to start or expand a PFML program, they would need external financial support.

4. Investment in the implementation phase is crucial.

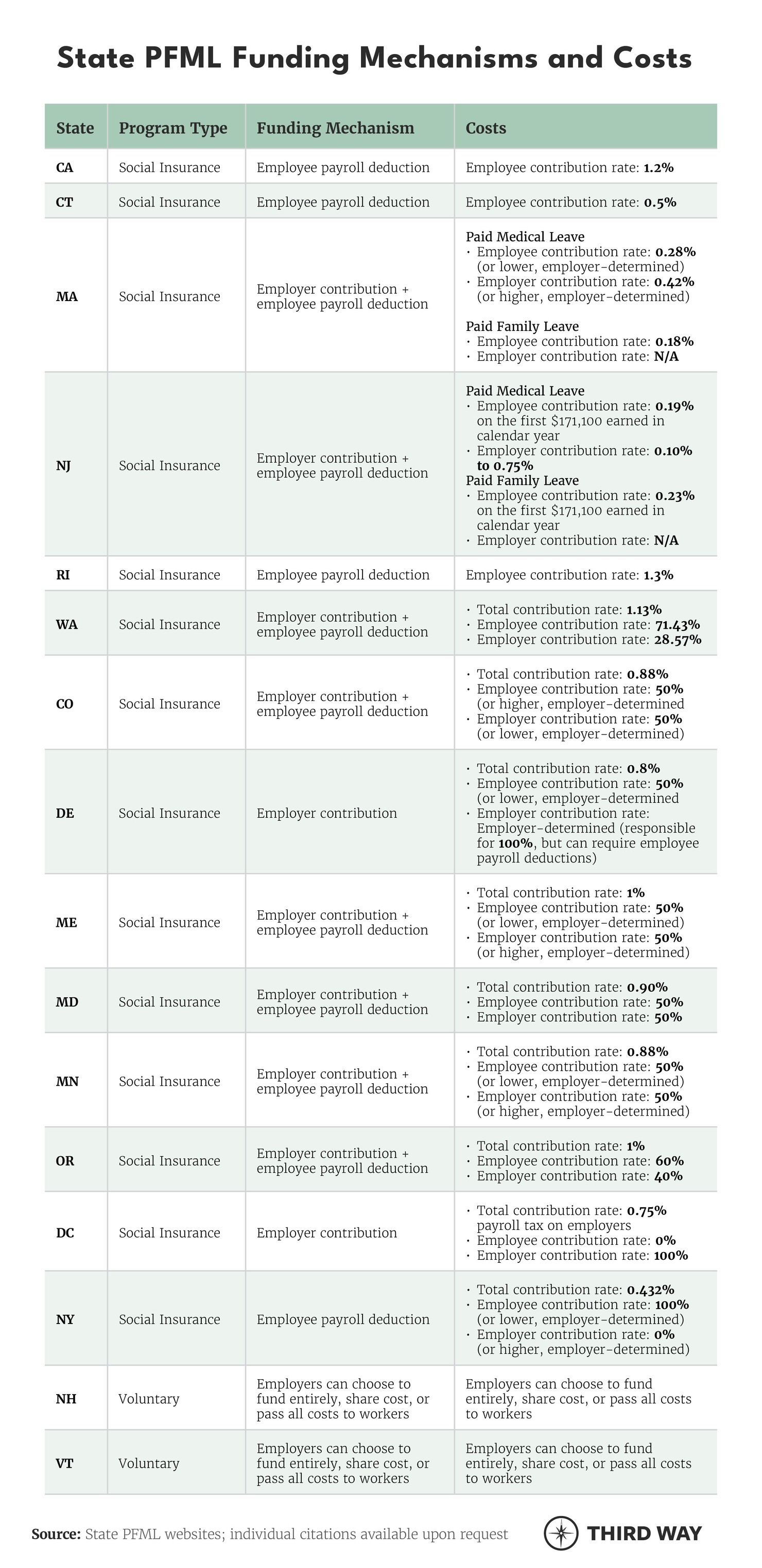

Most states and private insurance companies fund PFML benefits through some combination of employee and employer contributions.47 This means that funds are deducted either entirely from employees, entirely from employers, or from both groups as a shared cost.48 In states with social insurance programs, this is seen as a payroll tax. In states with voluntary programs that use insurance companies, this is usually called a premium. Each state or insurance company determines its own contribution rate, which is the percentage of an employee’s or employer’s income that is redirected to a PFML fund.49

These contributions make a PFML program self-sustaining. As employees and/or employers pay into the program on a regular basis, it creates a consistent flow of funds that are available whenever employees require leave.50 But it can take time to reach this point. When launching a social insurance PFML program, administrators must determine how to pay for benefits until the program becomes self-sustaining.51 While states with voluntary and state employee-only programs may also face this challenge, these programs are very specific to the individual insurance company or state agency administering the benefits. As a result, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about funding mechanisms and costs in those states.

Most state governments overseeing social insurance programs allocate part of the state’s general budget to PFML during the program’s early stages.52 This early investment is critical, as some new programs struggle in the implementation phase due to budget constraints. Maryland, for instance, has pushed back its PFML start date three times, citing both state and federal budgetary issues as the reason for the delay.53 Once a PFML program becomes self-sustaining, the state usually fully transitions from its general budget to payroll contributions to pay for benefits.54

The table in Appendix A highlights current PFML funding mechanisms and costs, primarily focusing on states with social insurance programs, but also the few voluntary programs with a single PFML insurance provider.

Nine Considerations for Federal Policymakers

In the absence of a robust and comprehensive federal paid leave program, states continue to expand access to paid leave through a national patchwork of policies and regulations. While there is no bipartisan federal leave policy on the immediate horizon, policymakers can strive for progress on paid leave without impeding longer-term efforts to establish a federal program. In fact, many of these incremental ideas would assist future federal efforts.

Here are nine key ways that federal policymakers can provide more paid leave for more people until we get a comprehensive law. These actions fall under two buckets: actions that would help states move forward with their efforts now, and actions that lay the groundwork for a federal program or policy in the future.

Helping States Make Progress

With more and more states pursuing their own programs, federal policymakers are well positioned to help states, regardless of where they are in their paid leave journey.

1. Establish the Interstate Paid Leave Action Network (I-PLAN).

Introduced in late 2024 as part of the bipartisan More Paid Leave for More Americans Act, I-PLAN would create a national framework that helps states coordinate paid leave benefits, share data, and reduce headaches for workers who live and work across different states.55 Harmonizing state efforts and establishing stronger data-sharing practices will make it easier for workers to access essential benefits. I-PLAN will also lay the groundwork for implementation of comprehensive federal efforts in the future.56

2. Support the expansion of state social insurance programs and improvements to voluntary programs.

Federal policymakers should provide states with the support needed to get their programs off the ground. For states with newer programs, federal support should help them prepare to launch their benefit systems in a timely manner. This may be especially helpful in states, like Maryland, that have had to push back their timeline due to implementation roadblocks.57

For more mature programs, federal support should include reimbursing states for administrative costs to encourage them to expand benefits.58 While voluntary programs are relatively new, federal policymakers can help support the maturation of these efforts. They should do this by incentivizing states to expand the types of leave offered or the amount of leave an employee can take. For example, if the voluntary program only includes parental leave, a grant program could help it expand to medical or caregiving as well.

In states where there is no state paid leave program, federal support may help get a smaller-scale effort off the ground. It could also fund technical assistance to help states explore how to offer paid leave at the state level. One way federal policymakers could achieve this is via the House Bipartisan Paid Leave Working Group’s Public-Private Partnerships Act, which would incentivize states to establish their own paid leave programs through a public-private partnership model.59

3. Give small businesses the ability to join group paid family leave insurance plans.

It is important that small businesses are not left behind as more states implement voluntary paid leave programs. Helping them provide these benefits to their employees will expand the pool of workers who can access PFML. It also expands smaller employers’ awareness of paid leave programs and their benefits. Increasing the share of small businesses utilizing voluntary paid leave programs also better positions these employers to navigate employee leave requests if their state or the federal government passes a social insurance program.

As part of their ongoing effort to make progress on paid leave, the House Bipartisan Family Leave Working Group released a policy framework outlining four areas where they see opportunity for legislative agreement. One would give small employers the ability to join an association-style insurance pooling plan, similar to what small businesses can now do with retirement benefits.60 The working group also suggested there may be bipartisan support for incentivizing businesses with more low-income workers to join a risk-sharing pool.61

4. Boost efforts to increase program awareness among all types of leave programs.

Federal policymakers can help states increase employees’ knowledge and use of paid leave opportunities. A paid leave program’s success depends on ensuring eligible workers are aware of their state’s paid leave policy and know how to access its benefits. Uptake can be hindered when workers have only limited understanding of eligibility rules or enrollment processes; this is especially a concern with low-income workers.62 Some states have had success partnering with state and community-based agencies that help disperse information on paid leave benefits.63

Policymakers at the federal level should help fund and facilitate these efforts. Federal policymakers could also provide technical assistance support to help states broadcast information on paid leave programs via online channels. Support could help ensure that program information is clearly marked with state seals to create credibility and consistency, or that application details are properly translated for people who may need it.64

Federal funding could also support the establishment and utilization of paid leave navigators or broader benefit navigators who could also provide information on paid leave benefits.65 Navigator systems already exist in many states for other federal public benefit programs like SNAP. They can help workers understand their benefit eligibility and the process for taking paid leave.66

5. Invest in understanding barriers to program utilization by workers and employers.

With more states providing leave, it is critical to understand the barriers workers face in understanding and accessing their benefits. It is also essential to know how employers, especially smaller ones, are faring when it comes to navigating the state system.

Providing states with funds to collect data on program uptake, participant coverage, and type of leave taken will help legislators better understand gaps in existing policy and how to alleviate roadblocks to worker coverage. Beyond just understanding where barriers exist, policymakers should also look to help workers and employers better navigate these challenges. For example, they could provide funding to help small businesses backfill roles for workers on leave or invest in broader training efforts to help employers and workers navigate the administrative side of the system.

Planning for a Federal Policy

Policymakers should be prepared to act when the political climate is more receptive to a national PFML program. State efforts can provide valuable insights into how to effectively implement broad PFML legislation. Understanding states’ successes and failures can help lawmakers design a federal PFML policy that encourages uptake and reaches workers who need support the most.

6. Use progressive wage replacement rates.

A progressive wage replacement rate is crucial to an accessible and affordable federal PFML program. States with progressive rates have seen high program uptake, likely because more low-income workers take PFML when they know they can afford the time off.67 By implementing a progressive rate, lawmakers can provide PFML to more people without breaking the bank. While lower-income workers may receive, for example, 80–90% of their regular income, higher earners might get 50–60%, balancing out the costs of the program while still ensuring that basic income needs are met. This fiscally responsible approach ensures all workers get the support they need while keeping the program solvent.

7. Ensure any progress includes protections for low-wage workers.

PFML is frequently inaccessible for low-wage employees, even in states where PFML usage among all workers has increased over the years. This is often due to burdensome eligibility requirements, such as requiring workers to reach a certain number of hours or earnings before taking PFML.68 Many low-wage employees work in hospitality, leisure, and other industries that disproportionately offer part-time and temporary work, preventing them from reaching the PFML qualification threshold.69 Additionally, low-income workers are historically less likely to report knowing that PFML benefits are available.70

It is therefore important to ensure that any federal PFML policy includes protections for low-wage workers. This could include reducing time and earning eligibility requirements, ensuring that all workers (full-time, part-time, temporary, seasonal, etc.) are covered under the policy, guaranteeing job protection, and improving outreach to increase program awareness.71

8. Offer a sliding scale of contribution rates for employers based on company size.

Lawmakers looking to expand PFML access should offer a sliding scale of contribution rates to employers based on company size as a way of reducing the burden on smaller businesses. Several states with social insurance programs that rely on combined employer and worker contributions offer lower rates for smaller employers. Cutoffs and adjusted premiums vary by state. In Colorado, this rate reduction is limited to businesses with less than 10 employees, which are responsible for paying half of the regular employer contribution.72 Washington state goes much further, exempting businesses with up to 49 workers from paying the entire employer portion of the premium.73 A sliding scale could be helpful for small businesses struggling to afford PFML, allowing them to obtain benefits without sticking a large price tag on the legislation.

9. Ensure any program includes a robust amount of leave.

Offering a robust amount of time off for leave is another important aspect of a federal PFML policy. States usually provide between six and 26 weeks, and states with longer leave durations see higher program uptake.74

In both the United States and the broader world, extended paid leave is associated with improved employee retention, as well as better maternal and child health outcomes.75 American businesses such as Google and Aetna, for example, reported lower attrition rates for both female and low-wage workers after extending their paid leave programs.76 Additionally, European countries that increased their paid leave duration saw a reduction in infant mortality.77

Conclusion

PFML supports employers, employees, and the overall economy. The benefits improve child and maternal health, increase women’s earnings and participation in the labor force, support big and small businesses, and stimulate economic growth.78 They also reflect reality: most workers will need time off to care for themselves, an ill family member, or a new baby at some point in their lives. Without access to paid leave, many low-to-middle income workers are forced to choose between weeks of lost wages and risking their health or their family’s well-being.

In the absence of a federal paid family and medical leave program, states are increasingly implementing policies to help workers access these important benefits. Some states, particularly those with social insurance programs, progressive wage replacement rates, and longer durations of paid leave, have seen high PFML uptake by workers across all income levels. Others, however, struggle to engage qualified employers and their eligible workers. Small businesses and low-income workers in particular are often priced out of the program.

Even if a national PFML program is currently out of reach, state and federal policymakers should be actively working to advance and improve PFML programs. By supporting state efforts and planning for federal paid leave legislation, policymakers can enhance the health, well-being, and economic security of America’s working families.

Appendix A