Report Published January 24, 2011 · Updated January 24, 2011 · 14 minute read

A National Infrastructure Bank

Ryan McConaghy & Jim Kessler

America’s economic future will hinge on how fast and well we move people, goods, power, and ideas. Today, our infrastructure is far from meeting the challenge. Upgrading our existing infrastructure and building new conduits to generate commerce will put people to work quickly in long-term jobs and will create robust growth. Funding for new infrastructure will be a crucial investment with substantial future benefits, but the current way that Congress doles out infrastructure financing is too political and wasteful. A National Infrastructure Bank will provide a new way to harness public and private capital to bridge the infrastructure gap, create jobs, and ensure a successful and secure future.

THE PROBLEM

America’s investment in infrastructure is not sufficient to spur robust growth.

In October, Governor Chris Christie announced his intention to terminate New Jersey’s participation in the Access to the Region’s Core (ARC) Tunnel project, citing cost overruns that threatened to add anywhere from $2-$5 billion to the tunnel’s almost $9 billion price tag. At the time, Christie stated, “Considering the unprecedented fiscal and economic climate our State is facing, it is completely unthinkable to borrow more money and leave taxpayers responsible for billions in cost overruns. The ARC project costs far more than New Jersey taxpayers can afford and the only prudent move is to end this project.”1 Despite the fact that the project is absolutely necessary for future economic growth in the New Jersey-New York region and would have created thousands of jobs, it was held captive to significant cost escalation, barriers to cooperation between local, state, and federal actors, and just plain politics.

Sadly, these factors are increasingly endemic in the execution of major infrastructure projects. America’s infrastructure has fallen into a state of disrepair, and will be insufficient to meet future demands and foster competitive growth without significant new investment. However, the public is fed up with massive deficits and cost overruns, and increasingly consider deficit reduction to be a bigger economic priority than infrastructure investment.2 They have lost confidence in government’s ability to choose infrastructure projects wisely, complete them, and bring them in on budget.

At the same time, traditional sources of funding are strained to the breaking point and federal support is hindered by an inefficient process for selecting projects. Finding the resources necessary to construct new infrastructure will be also be a significant challenge. A new of way of choosing and funding infrastructure projects—from roads, bridges, airports, rail, and seaports to broadband and power transmission upgrades—is necessary to ensure growth and create jobs in America.

America’s infrastructure isn’t ready to meet future growth needs.

The safety risks and economic costs associated with the deterioration of America’s infrastructure are increasingly apparent across multiple sectors. The American Society of Civil Engineers has awarded the nation’s overall infrastructure a grade of D.3 Since 1990, demand for electricity has increased by about 25% but construction of new transmission has decreased by 30%.4 Over about the last 25 years, the number of miles traveled by cars and trucks approximately doubled but America’s highway lane miles increased by only 4.4%.5 Over 25% of America’s bridges are deficient6 and about 25% of its bus and rail assets are in marginal or poor condition.7 America’s broadband penetration rate ranks only 14th among OECD countries.8

As America’s population and economic activity increases, the stress on its infrastructure will only grow. The number of trucks operating daily on each mile of the Interstate Highway system is expected to jump from 10,500 to 22,700 by 2035,9 while freight volumes will have increased by 70% over 1998 levels.10 It is also expected that transit ridership will double by 2030 and that the number of commercial air passengers will increase by 36% from 2006 to 2015.11 Total electricity use is projected to increase by 1148 billion kWh from 2008 to 2035.12 In order to cope, America’s infrastructure will need a significant upgrade.

America’s infrastructure deficit hurts its competitiveness and is a drain on the economy.

America’s infrastructure gap poses a serious threat to our prosperity. In 2009, the amount of waste due to congestion equaled 4.8 billion hours (equivalent to 10 weeks worth of relaxation time for the average American) and 3.9 billion gallons of gasoline, costing $115 billion in lost fuel and productivity.13 Highway bottlenecks are estimated to cost freight trucks about $8 billion in economic costs per year,14 and in 2006, total logistics costs for American businesses increased to 10% of GDP.15 Flight delays cost Americans $9 billion in lost productivity each year,16 and power disruptions caused by an overloaded electrical grid cost between $25 billion and $180 billion annually.17 These losses sap wealth from our economy and drain resources that could otherwise fuel recovery and growth.

The infrastructure gap also hinders America’s global competitiveness. Logistics costs for American business are on the rise, but similar costs in countries like Germany, Spain, and France are set to decrease.18 And while America’s infrastructure spending struggles to keep pace,19 several main global competitors are poised to make significant infrastructure enhancements. China leads the world with a projected $9 trillion in infrastructure investments slated for the next ten years, followed by India, Russia, and Brazil.20 In a recent survey, 90% of business executives around the world indicated that the quality and availability of infrastructure plays a key role in determining where they do business.21 If America is going to remain on strong economic footing compared to its competitors, it must address its infrastructure challenges.

There are too many cost overruns and unnecessary projects—but not enough funds.

Cost overruns on infrastructure projects are increasingly prevalent and exact real costs. One survey of projects around the world found that costs were underestimated for almost 90% of projects, and that cost escalation on transportation projects in North America was almost 25%.22 Boston’s Central Artery/Tunnel Project (a.k.a. the “Big Dig”) came in 275% over budget, adding $11 billion to the cost of the project. The construction of the Denver International Airport cost 200% more than anticipated. The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge retrofit project witnessed overruns of $2.5 billion—more than 100% of the original project cost—before construction even got underway.23 And of course, there are the “bridge to nowhere” earmarks that solve a political need, but not an economic one.

The current system for funding projects is subject to inefficiency and bureaucratic complication. Funding for infrastructure improvements is divided unevenly among federal, state, local, and private actors based on sector.24 Even in instances where the federal government provides funding, it has often ceded or delegated project selection and oversight responsibilities to state, local, and other recipients, weakening linkages to federal program goals and efforts to ensure accountability.25 Federal efforts are also hampered by organization and funding allocations based strictly on specific types of transportation, as opposed to a system-wide approach, which create inefficiencies that hinder collaboration and effective investment.26 Complicating matters even further are the emergence of multi-state “megaregions,” which have common needs that require multijurisdictional planning and decision making ability.27

Infrastructure funding has also become significantly politicized. Congressional earmarking in multi-year transportation bills has skyrocketed from 10 projects in the STAA of 1982 to over 6,300 projects in the most recent bill (SAFETEA-LU).28

Even under a working system, the infrastructure improvements necessary to foster growth will require substantial investment. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that it would require $2.2 trillion over the next five years to bring our overall infrastructure up to par.29

However, sources of funding for infrastructure improvements are under significant strain and may not be sufficient.30 The Highway Trust Fund has already experienced serious solvency challenges, and inadequate revenues could lead to a $400 billion funding shortfall from 2010 to 2015.31 The finances of state and local governments, which are responsible for almost three-quarters of public infrastructure spending,32 have been severely impaired. At least 46 states have budget shortfalls in the current fiscal year, and it is likely that state financial woes will continue in the near future.33 In a recent survey by the National Association of Counties, 47% of respondents indicated more severe budget shortfalls than anticipated, 82% said that shortfalls will continue into the next year, and 54% reported delaying capital investments to cope.34

THE SOLUTION

A National Infrastructure Bank

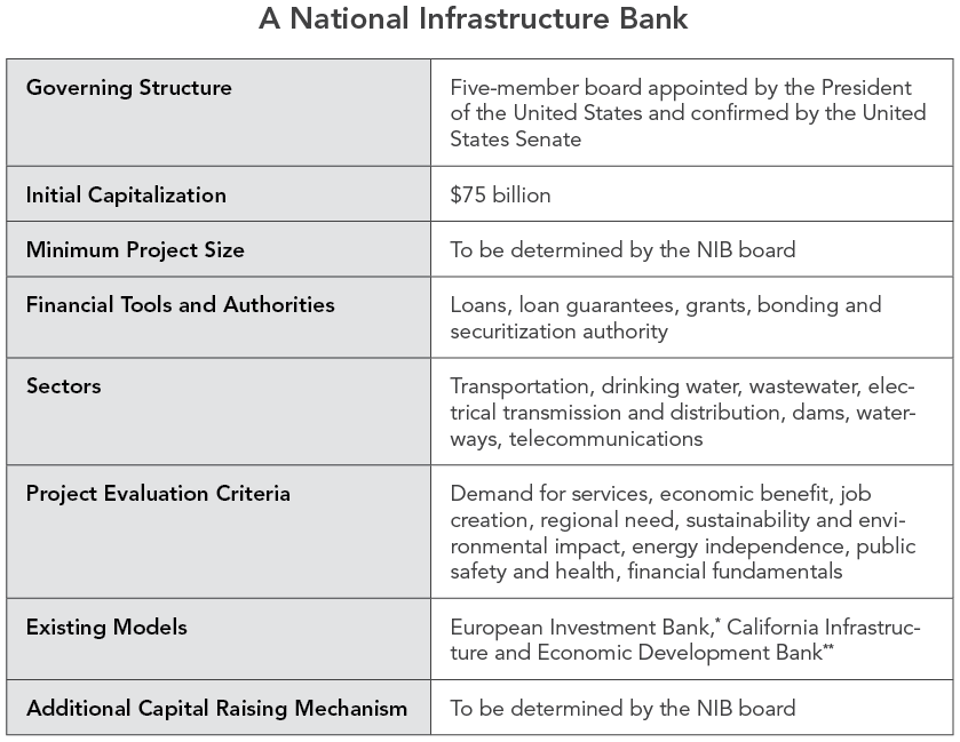

In order to provide innovative, merit-based financing to meet America’s emerging infrastructure needs, Third Way supports the creation of a National Infrastructure Bank (NIB). The NIB would be a stand-alone entity capitalized with federal funds, and would be able to use those funds through loans, guarantees, and other financial tools to leverage private financing for projects. As such, the NIB would be poised to seize the opportunity presented by historically low borrowing costs in order to generate the greatest benefit for the lowest taxpayer cost.

Projects would be selected by the bank’s independent, bipartisan leadership based on merit and demonstrated need. Evaluation criteria may include economic benefit, job creation, energy independence, congestion relief, regional benefit, and other public good considerations. Potential sectors for investment could include the full range or any combination of rail, road, transit, ports, dams, air travel, clean water, power grid, broadband, and others.

The NIB will reform the system to cut waste, and emphasize merit and need.

As a bank, the NIB would inject accountability into the infrastructure investment process. Since the bank would offer loans and loan guarantees using a combination of public and private capital, it would have the opportunity to move away from the traditional design-bid-build model and toward project delivery mechanisms that would deliver better value to taxpayers and investors.35 By operating on principles more closely tied to return on investment and financial discipline, the NIB would help to prevent the types cost escalation and project delays that have foiled the ARC Tunnel.

America’s infrastructure policy has been significantly hampered by the lack of a national strategy rooted in clear, overarching objectives used to evaluate the merit of specific projects. The politicization and lack of coordination of the process has weakened public faith in the ability of government to effectively meet infrastructure challenges. In polling, 94% of respondents expressed concern about America’s infrastructure and over 80% supported increased federal and state investment. However, 61% indicated that improved accountability should be the top policy goal and only 22% felt that the federal government was effective in addressing infrastructure challenges.36 As a stand-alone entity, the NIB would address these concerns by selecting projects for funding across sectors based on broadly demonstrated need and ability to meet defined policy goals, such as economic benefit, energy independence, improved health and safety, efficiency, and return on investment.

The NIB will create jobs and support competitiveness.

By providing a new and innovative mechanism for project financing, the NIB could help provide funding for projects stalled by monetary constraints. This is particularly true for large scale projects that may be too complicated or costly for traditional means of financing. In the short-term, providing resources for infrastructure investment would have clear, positive impacts for recovery and growth. It has been estimated that every $1 billion in highway investment supports 30,000 jobs,37 and that every dollar invested in infrastructure increases GDP by $1.59.38 It has also been projected that an investment of $10 billion into both broadband and smart grid infrastructure would create 737,000 jobs.39 In the longer-term, infrastructure investments supported by the NIB will allow the U.S. to meet future demand, reduce the waste currently built into the system, and keep pace with competition from global rivals.

The NIB will harness private capital to help government pay for new projects.

The NIB would magnify the impact of federal funds by leveraging them through partnerships with private entities and other actors, providing taxpayers with more infrastructure bang for their public buck. Estimates have placed the amount of private capital readily available for infrastructure development at $400 billion,40 and as of 2007, sovereign wealth funds—another potential source of capital—were estimated to control over $3 trillion in assets with the potential to control $12 trillion by 2012.41 While these and other institutional funds have experienced declines as a result of the economic downturn, they will continue to be important sources of large, long-term investment resources.

By offering loan guarantees to induce larger private investments or issuing debt instruments and securities, the NIB could tap these vast pools of private capital to generate investments much larger than its initial capitalization. In doing so, it could also lower the cost of borrowing for municipalities by lowering interest on municipal bonds for state and local governments by 50 to 100 basis points.42

The NIB would also be poised to help taxpayers take full advantage of historically low borrowing costs. In 2010, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries reached a historic low of 3.22%, as compared to a rate of 6.03% in 2000 and a peak rate of 13.92% in 1981. Prior to the Great Recession, this rate had not dipped below 4% since 1962.43 By allowing government and private actors to access financing at historically low rates, the NIB would help to capitalize on a once-in-a-lifetime window to make enduring infrastructure investments.

CRITIQUES & RESPONSES

A National Infrastructure Bank

It’s too expensive.

Financing the infrastructure upgrades needed to support America’s economy and meet its new challenges won’t be cheap, but there are billions in efficiencies that can be wrung out of the system with real structural changes, and the economic costs of inaction will be higher. By leveraging private resources, the NIB will ensure that future spending on infrastructure will get the utmost bang for the taxpayer buck. It will also cut down on waste by supporting only projects that serve demonstrated regional or national needs and satisfy goal-based criteria.

Won’t this just turn into another big-spending program or bailout? How will the bank be repaid on investments in infrastructure?

No, loans and financing issued by the NIB could be repaid by recipients. The existing European Investment Bank raises capital in the private markets and lends it at a higher interest rate in order to achieve profit and maintain sustainability.44 Repayments on infrastructure assets are often derived from tolls and user fees, but can be provided through other means such as availability payments and gross revenues.45 As part of its project evaluation criteria, the NIB would be required to assess repayment prospects and to ensure that it remains a viable entity.

Won’t the bank be too small to meet our infrastructure needs? Won’t it threaten other, existing funding streams and programs?

The NIB would be an additional tool to support infrastructure investment by leveraging private capital and by improving the project selection process. By doing so, the NIB would make a significant contribution to meeting America’s infrastructure needs, but the scope of demand is too great for any one program to address completely. The reforms embodied by the NIB can help to shape improvements in other programs, but the NIB is not intended to and would not be capable of completely replacing existing federal infrastructure programs. The NIB would be capitalized separately from other streams of program funding, and would assess and fund projects independently.

Wouldn’t this proposal transfer decisions over significant federal spending to an independent, largely unaccountable government entity?

No. The officials in charge of decision making at the bank would still be appointed by and answerable to elected officials. The NIB would be similar to several other successful institutions, such as the FDIC, which have been able to successfully and independently perform their duties with sufficient oversight. Institutions such as the California Infrastructure and Development Bank and European Investment Bank have shown that an infrastructure bank can operate effectively and be accountable.

Didn’t the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act already include a large amount of funding for infrastructure projects?

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act included over $70 billion to begin to address America’s infrastructure deficit.46 While that figure represents an important down payment on America’s infrastructure needs, it does not approach the funding levels necessary to close the infrastructure gap or to reform the investment system. America still needs a long-term financing solution that reforms the process and harnesses private capital to fully bridge the infrastructure gap.

Appendix

* European Investment Bank. Available at: http://www.eib.org/

** California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank. Available at: http://www.ibank.ca.gov/.