Report Published February 5, 2024 · 13 minute read

A Democratic Case for Fiscal Responsibility

Zach Moller, Anthony Colavito, Gabe Horwitz, & Annie Shuppy

The numbers don’t lie—we have reached the point where making progress on the next generation of Democratic priorities isn’t possible without a newfound commitment to fiscal responsibility.

Democrats are generally more fiscally responsible than Republicans. But flirtation with Modern Monetary Theory, recent inflation, and the pervasive belief from voters that Republicans are better on the economy means Democrats have a policy and political problem.1

We’ve used many fiscal bandages to cover problems, please constituencies, and get political deals. But no party, and very few policymakers, have realized it’s in their interest to rip them off. This report lays out five reasons why Democrats must not only pay for policies but also slow the projected growth of the national debt:

- We’re burning money rather than investing in our causes.

- The current budget neglects kids in favor of seniors.

- We’re lying to ourselves about the Social Security challenge.

- Revenue is leaking everywhere.

- Republicans attack progressive spending like a rabid dog.

This report is the first in a series of papers through 2025 focusing on the deep fiscal challenges and opportunities within the United States. Our next report will take Republicans to task and show reasons they need to turn away from their profligate ways.

We’re burning money rather than investing in our causes.

Interest cost on the national debt is the fastest-growing piece of the budget. But why should Democrats care? Because it’s all about priorities—and spending more on interest means functionally having less ability to spend on kids, national parks, food inspectors, and more.

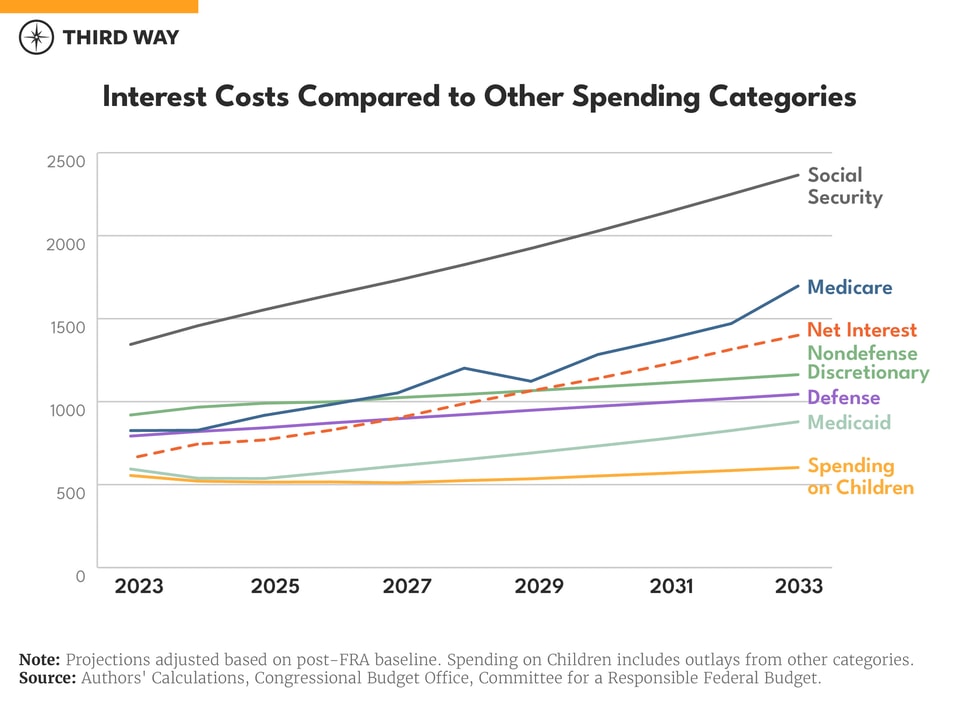

The United States will pay $1 trillion in yearly interest costs as early as 2029, and interest will eventually consume more than 14% of the federal budget. For comparison, interest only accounted for around 6% of the budget a decade ago.2

The problem is, unlike an aircraft carrier or a social security check, spending on interest is not productive. We might as well burn it. When the government must devote a larger share of its budget to servicing the debt, it means fewer resources for other priorities. Interest already exceeds spending on children and Medicaid spending, and it will likely exceed all defense discretionary spending by 2027. That’s if we are lucky. In 2023 the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) underestimated where interest rates are. Final interest costs for FY 2023 ended up being 3% larger than projected at the beginning of 2023.3

Small changes in interest rates can also lead to big swings in interest costs over a decade. For example, if we correct for this under-estimate (which would roughly mean interest rates are just 0.2 percentage points higher in FY 2024 and just 0.1 percentage points higher in later years), total net interest costs over the decade would increase by $275 billion.4

Interest payments on the debt are the costs of past decisions. The next generation will have no say on the choices that led to these expenses that our kids and their kids will be paying for with taxes and potential cuts to government services.

It is time to rethink this preference for borrowing, which is no longer as cheap as it was in the 2010s due to inflation and a robust economic recovery from the COVID recession. But it’s clear that continuing on the current path of higher and higher interest payments would be a mistake for the spending priorities of Democrats. Making choices and prioritizing other spending can reduce the pressure interest is placing on the spending and fiscal position of the United States.

The current budget neglects kids in favor of seniors.

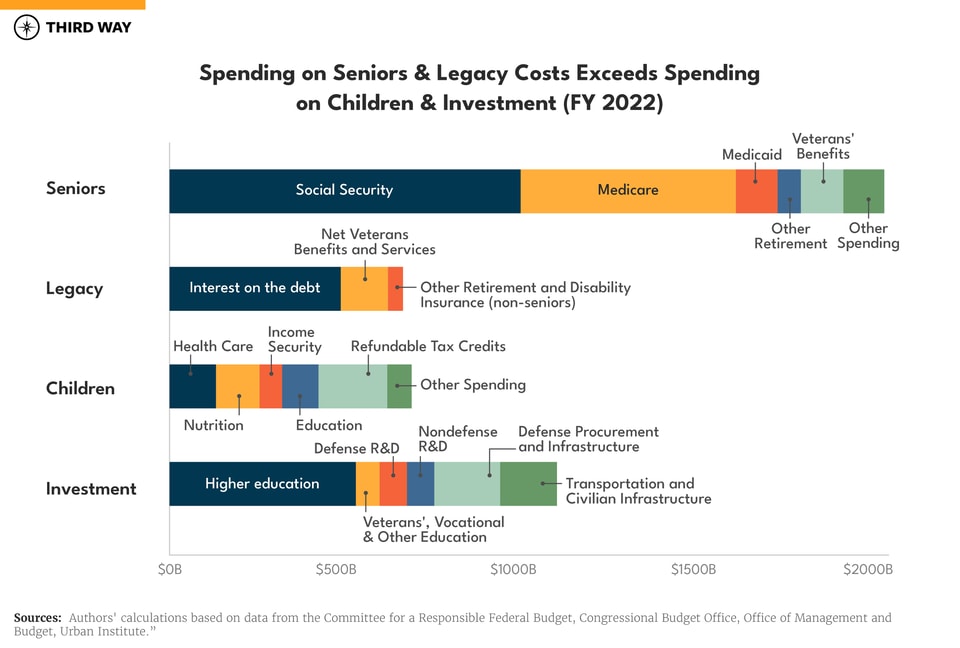

We’re spending far more on past obligations—seniors and legacy federal costs such as interest or federal employee retirement—than we are on the future—children and investment. In FY 2022, we spent $3 that benefited the oldest generation for every dollar spent on the youngest generation. And that ratio is growing—it will likely increase to more than $4 in this fiscal year.5

In FY 2022, spending on children made up nearly 11% of the federal budget.6 For FY 2023, spending on children will likely fall to below 9% of the budget and continue to fall to 8% of the budget in FY 2024.7 And if the American Rescue Plan Act’s enhanced child tax credit returned, it would only increase children’s share of the federal budget by about one percentage point.8

Besides spending on children, the broader investment budget is also a small share of federal spending.9 In FY 2022, investment spending made up 17% of the budget, which is nearly 7 percentage points higher than the level from the previous year due to the student loan policy. For FY 2023, spending on investment will be roughly 12% of the budget and fall slightly to just over 11% of the budget in FY 2024.10 Meanwhile, other legacy costs of the federal government (like interest and other past promises) were 10% in FY 2022 and will rapidly grow as interest payments grow.11

If we look at these broader categories, for every dollar the federal budget dedicated to future-oriented spending in FY 2022, it spent about $1.50 on past obligations and older generations. Over the next two years, this ratio of past spending to future spending will likely increase to more than $2.12

We’re lying to ourselves about the Social Security challenge.

Without rescue, Social Security—one of Democrats’ greatest achievements—will fail to pay the full benefits beneficiaries expect. That’s never happened before. The challenge is great, and the solutions are far from simple.

After 2020, what went into Social Security (income from taxes and trust fund interest) has been less than the benefits being paid out. Simply put, the trust fund is shrinking.13 In as soon as 10 years, these assets will run out.14 At that point, Social Security will no longer be able to meet its obligations in full. To continue paying beneficiaries, adjustments will need to be made.

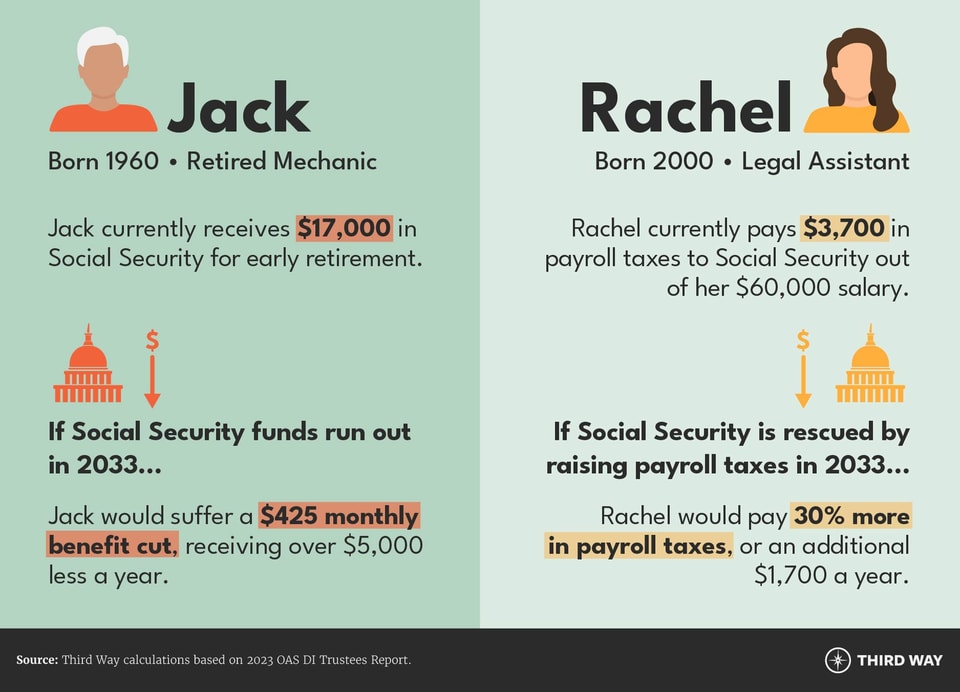

To put the trust fund problem into perspective, picture two people today: Jack and Rachel. Jack, born in 1960, began working as a mechanic earning the average wage after graduating high school. Due to the physical strain of his job, Jack retired and began claiming Social Security early, at age 62, receiving $1,400 a month (or $17,000 a year).15 Rachel, born in 2000, graduated college and started working as a legal assistant, earning $60,000 a year, and contributes $3,700 a year from her paycheck to Social Security.16

If the trust fund runs out, funding for Social Security benefits would be short by 23%. In 2033, Jack would suffer a $425 monthly benefit cut, receiving over $5,000 less a year. If Congress decided to raise payroll taxes instead, Rachel and her employer would each pay 30% more in Social Security payroll taxes, or an additional $1,700 a year.17 And if Congress decided to borrow funds to fill the gap, both would be saddled with higher interest rates on their credit card debt, car payments, and mortgages—all while they and future generations become responsible for managing larger deficits. This isn’t fearmongering; it’s math.

Greater fiscal responsibility now can make these tradeoffs less painful. If any changes to benefits or revenues for Social Security happen in the next decade, that would lessen the impact at the moment of trust fund exhaustion.

Unfortunately, we are lying to ourselves if we think the fixes are simple. Many think there are two magic wands to wave to save Social Security: 1.) funding Social Security with a “costless” general fund transfer, and 2.) legislative proposals that raise taxes and broadly expand benefits. Yet, both have significant issues.

First, a general fund transfer is not a solution to the problem. It would mean that Social Security is explicitly not self-financing and disconnect benefits from payroll taxes. Benefits would be paid (or not) based on Congressional whims to increase taxes and/or issue more debt. Furthermore, this could create even more political pressure for spending cuts to other Democratic priorities and would have financial market ramifications as debt is issued to the open market instead of going to the trust fund.

Second, lifting the cap on revenue simply doesn’t get you close enough to solving the problem. There are a variety of legislative proposals out there that rely exclusively on new revenue while enacting benefit increases, including for high-income retirees. Some popular bills even make benefit increases temporary to mask their true long-term impact on the Trust Fund.18 But these proposals are legislative dead ends. While revenue will need to be the bedrock of improving Social Security’s finances, solely eliminating the wage cap on Social Security payroll taxes doesn’t get you there—especially coupled with benefit expansions for the very old and very poor that all Democrats support.19 In addition, there is a question of priorities. The more taxes Democrats commit to Social Security means less for kids, climate change, and more.

Revenue is leaking everywhere.

Our growing economy is not growing tax revenue like it used to. There are too many holes in the revenue collection bucket resulting from a litany of tax breaks, tax cuts, and insufficient tax enforcement. Fiscal responsibility requires fixing all of them.

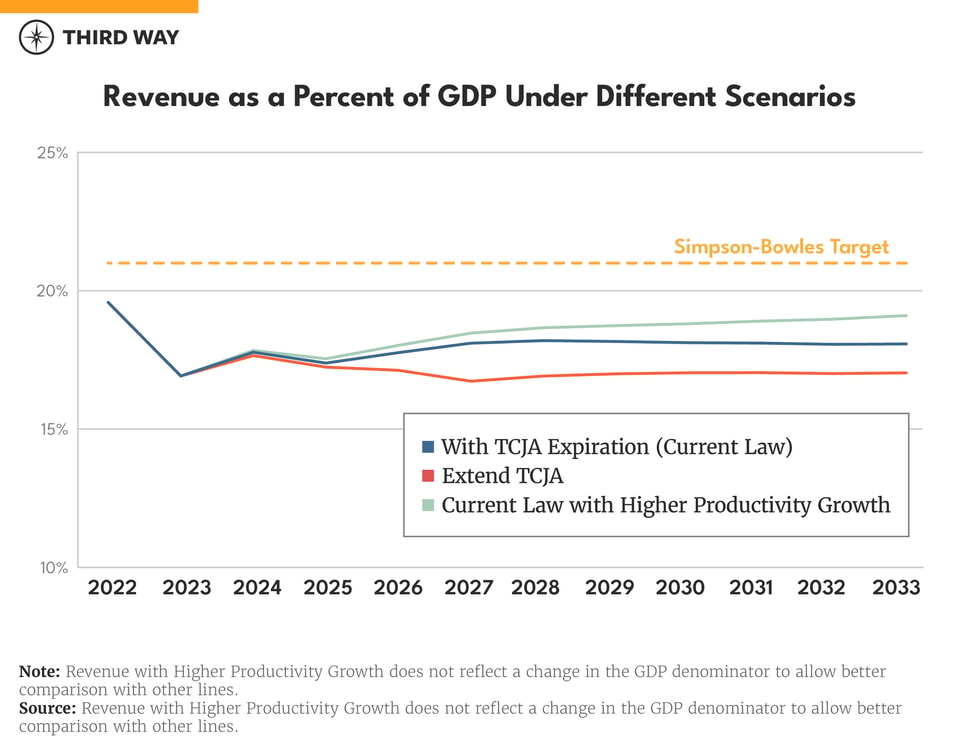

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, federal revenues were projected to be more than 18% of GDP in FY 2023. When final numbers for FY 2023 were released, they showed revenue falling below 17% of GDP. In addition, the final revenue totals were nearly $400 billion (8%) less than what CBO had predicted just a few months earlier.20

It’s not just the Trump tax cuts, though—we’ve been losing revenue for years. Since 2000, Republicans have had the White House and both chambers of Congress for eight years—during which they passed four budget reconciliation bills that lowered revenue and harmed the fiscal position of the country.21 According to one study by the Center for American Progress, without the Bush and Trump tax cuts and extensions, the debt would be $10 trillion (38 percentage points of GDP) lower.22 According to another study by American Enterprise Institute revenues would be over $700 billion a year larger by going back to the tax code of the late 1990s.23

Our weakened tax code is also beset with more tax cheats and noncompliance that are draining federal coffers. The most recent estimates from the IRS say that the gap in tax collections compared to what is owed has swelled to $688 billion per year. This is up from about half a trillion dollars a decade ago.24

Democrats made some progress on revenue. The Inflation Reduction Act raised $291 billion in gross revenue, including essential IRS enforcement funding to start to close some holes in the leaky bucket.25 But IRA revenue was $1.2 trillion shy of the House-passed Build Back Better Act, and it is less than 4% of the amount of deficit reduction needed to stabilize the debt as a share of our economy.26

Republicans will argue that growing the economy (or filling the bucket faster) will bolster revenue, but it’s not the solution to fiscal sustainability. If productivity growth, a proxy for real GDP growth, were 0.5 percentage points higher each year through the next decade, total revenue would be $1.9 trillion higher, and the path of debt-t0-GDP improves by only nine percentage points. Even this increase in productivity pushes the boundaries of what most government policy might do to sustained growth, let alone the unrealistic economic assumptions that Republican policymakers have used over time.27

At the end of 2025, substantial parts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act expire, and lawmakers will need to decide whether to punch more holes in the bucket and extend all the expiring tax provisions, just keep them for certain income brackets, or allow the individual tax rates and other provisions to revert to 2017 levels. Fully extending the TCJA would cost more than $3.8 trillion with interest through 2033, increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by 10 percentage points.28

Republicans attack progressive spending like a rabid dog.

Non-defense discretionary spending may sound like jargon, but it covers some of biggest Democratic priorities. And it’s under constant attack by Republicans. Twice in the past 13 years, Republicans held the debt limit hostage and non-defense discretionary (NDD) spending suffered.

Non-defense discretionary covers items that Democrats have champions for decades—medical research, transportation programs, space exploration and technology, federal education spending, veterans’ health care, border security, federal law enforcement, food and environmental inspection, clean water, infrastructure, and more. It is also how we deal with many emergencies—disaster funding, wildfire suppression, and certain COVID-19 response activities have all been funded with nondefense discretionary spending.

While lawmakers can come to an agreement on non-defense discretionary levels on a year-to-year basis, NDD spending is often the first place that Republican budgets look to cut to attempt to get to the overall budget to balance—from former House Speaker Paul Ryan to former President Donald Trump to the House Freedom Caucus.29

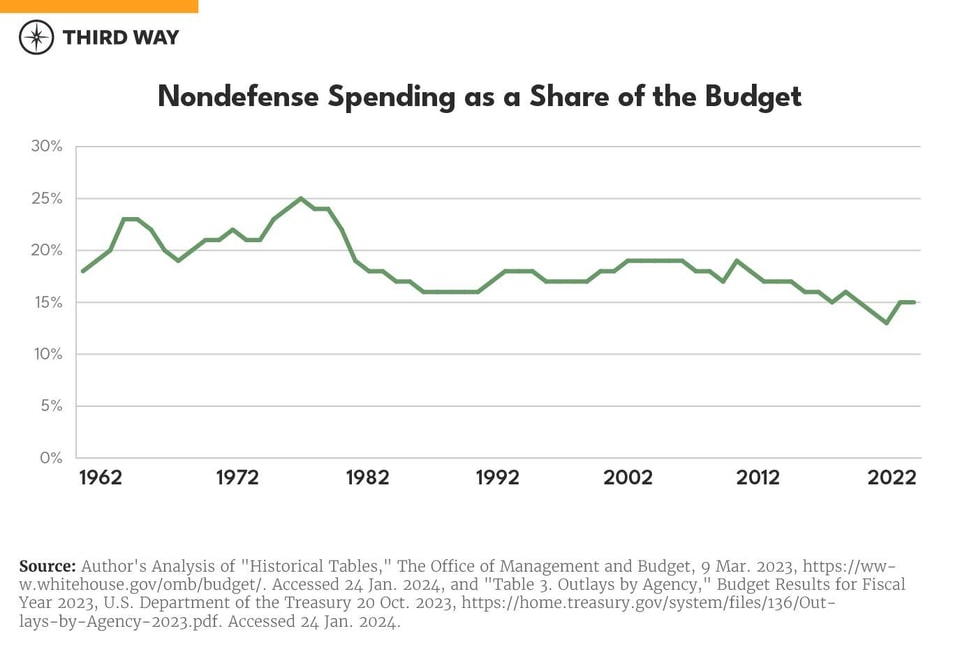

In FY 2023, nondefense discretionary spending made up slightly less than 15% of the federal budget, 10 percentage points down from its peak of 25% in 1978. The 1980s hammered NDD during the Reagan Administration.30

Nondefense discretionary spending tends to be more vulnerable to cuts because it is considered yearly, rather than being covered through multi-year funding streams or through open-ended entitlements. Annual defense spending is already funded at a higher level than base nondefense discretionary spending, and it tends to benefit from protection by members of Congress from both parties in both chambers.

As long as deficits remain high and Republican lawmakers feel pressured to look fiscally responsible, NDD spending will bear the brunt of that pressure.

What can be done?

Fiscal responsibility will require a mix of political will, common sense, and tradeoffs. It can put us on a path to a better more progressive tax code, solvent social security that can eliminate senior poverty, a health care system that puts patients over providers, greater room for discretionary spending priorities, and leaner (yet better) government.

To be sure the ideas below are not a comprehensive or detailed fiscal plan but are principles to help get us there:

- We need tax reform to increase revenue from those that can most afford it and to reduce tax distortions in our economy to maintain a pro-growth footing. And at the very least, we should not allow the 2025 tax debate to lower projected revenues below current law.

- A commission focusing only on improving the finances of Social Security would find the fairest way forward. A commission would balance the needs of promises of the past with equity for future generations. It would be a vehicle to examine many of the creative ideas people have put forward to improve Social Security solvency.

- Our health care system needs lower costs for patients and taxpayers. Health care reforms should reduce costs so everyone has access to care, insist on one bill for care instead of bill after bill, and promote innovations that reduce hassles for getting care.

- Certain programs and tax benefits should be better means-tested. This would create budget space so those who need government assistance or incentives get them.

- We need to promote thoughtful government efficiency and modernization where possible while building and rebuilding the administrative capacity to do important things quickly. In addition, making sure that program integrity efforts are at the forefront of administrators' minds will be key to making sure programs do what they are supposed to in order to minimize errors.

Conclusion

It’s time to face reality that the debt situation has changed over the past decade—it’s never been higher, and the cost of it both in a budget sense and for the American family is now a problem.

The rise in interest costs, the increasing bias towards past spending, the imperative to keep Social Security solvent, the pressures of shrinking revenue, and the continued vulnerability of nondefense discretionary spending all compel Democrats to care about growing deficits and debt. Democrats have been the advocates of fiscal responsibility before—and must do so again.