Memo Published October 24, 2023 · 5 minute read

The Future for Non-College Women Is Bleak

Curran McSwigan

New projections show a stark warning for women without a college degree: work is changing, and job security is poised to shrink. Over the next decade, non-college women are projected to face high rates of job loss, with estimates showing that two-thirds of jobs lost in the country’s top-declining industries will be ones currently held by women.1 Specifically, non-college women are slated to lose the most middle-wage jobs—jobs that have historically allowed them to provide for themselves and their family. And unless there is a surge in women moving into traditionally male-dominated professions, job growth for non-college women will be concentrated in the lowest-paying sectors.

In this analysis, we unpack new projections from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which predicts which occupations will see the most growth and decline based on current and anticipated employment trends. We focus on the industries that will see the largest number of new jobs as well as the occupations that will see the biggest drops in employment.

Non-college women face the biggest job declines.

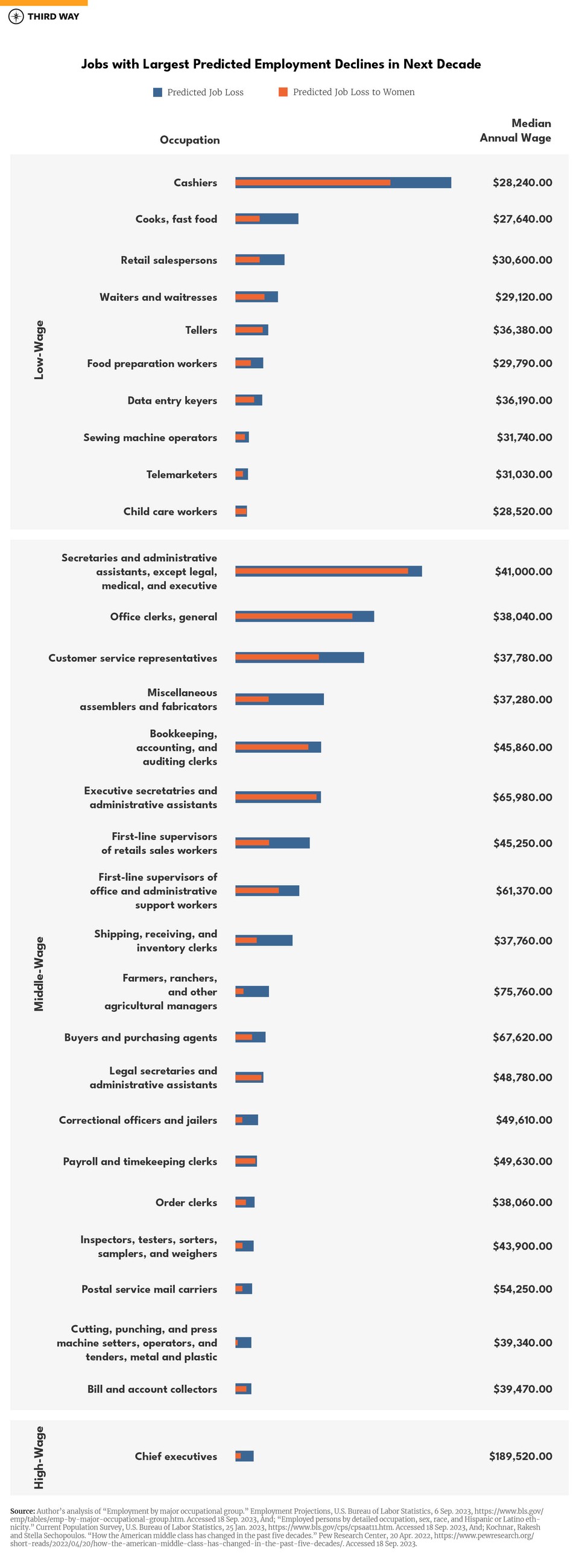

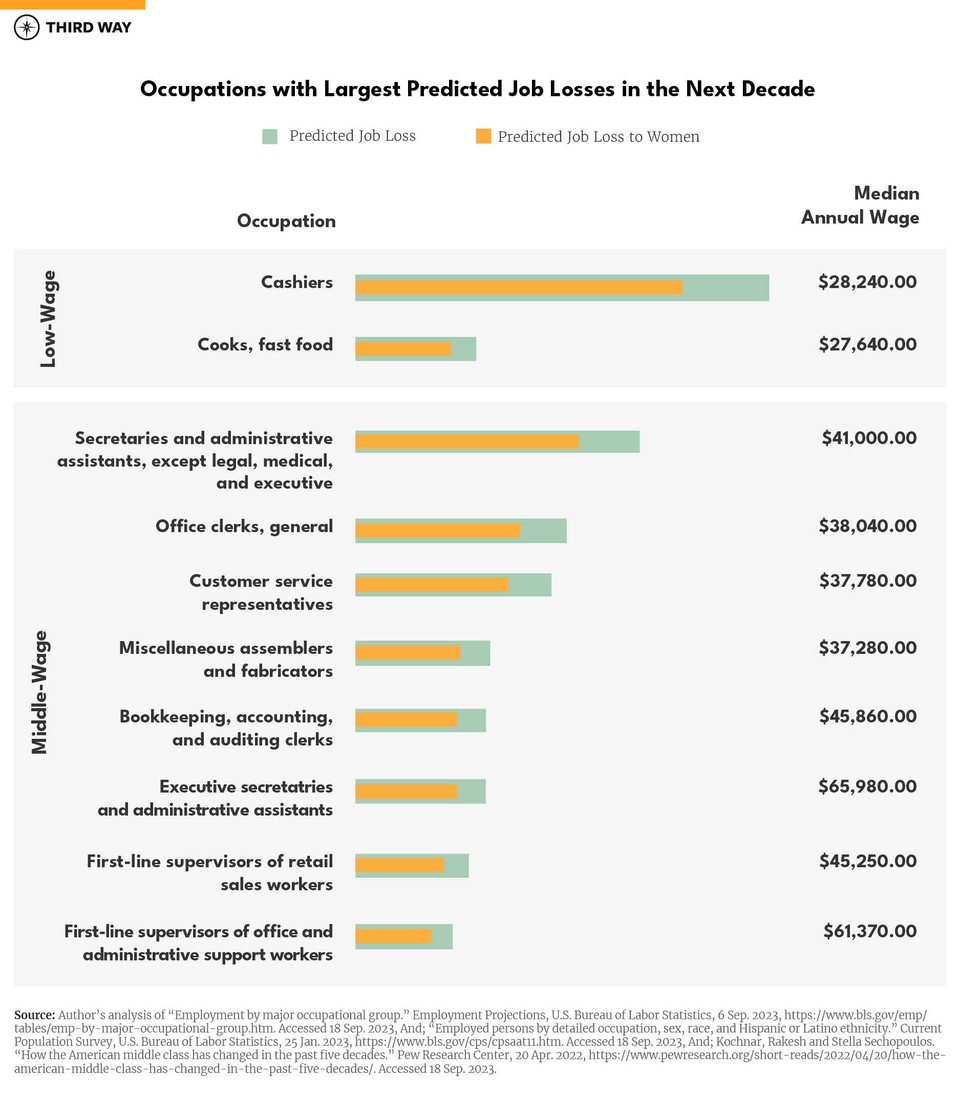

The BLS projects which industries are expected to lose the most jobs over the next 10 years—from cashiers (348,000 lost by 2032) to mail carriers (21,000 jobs lost by 2032).2 Within those industries, 97% of the jobs lost will be roles that don’t require a bachelor’s degree, and over 60% are middle-wage jobs.3 This decline will hurt workers without a degree the most. And based on the current gender breakdown of these occupations, two-thirds of jobs predicted to be eliminated will be ones held by women—meaning these losses will disproportionately impact non-college women.4

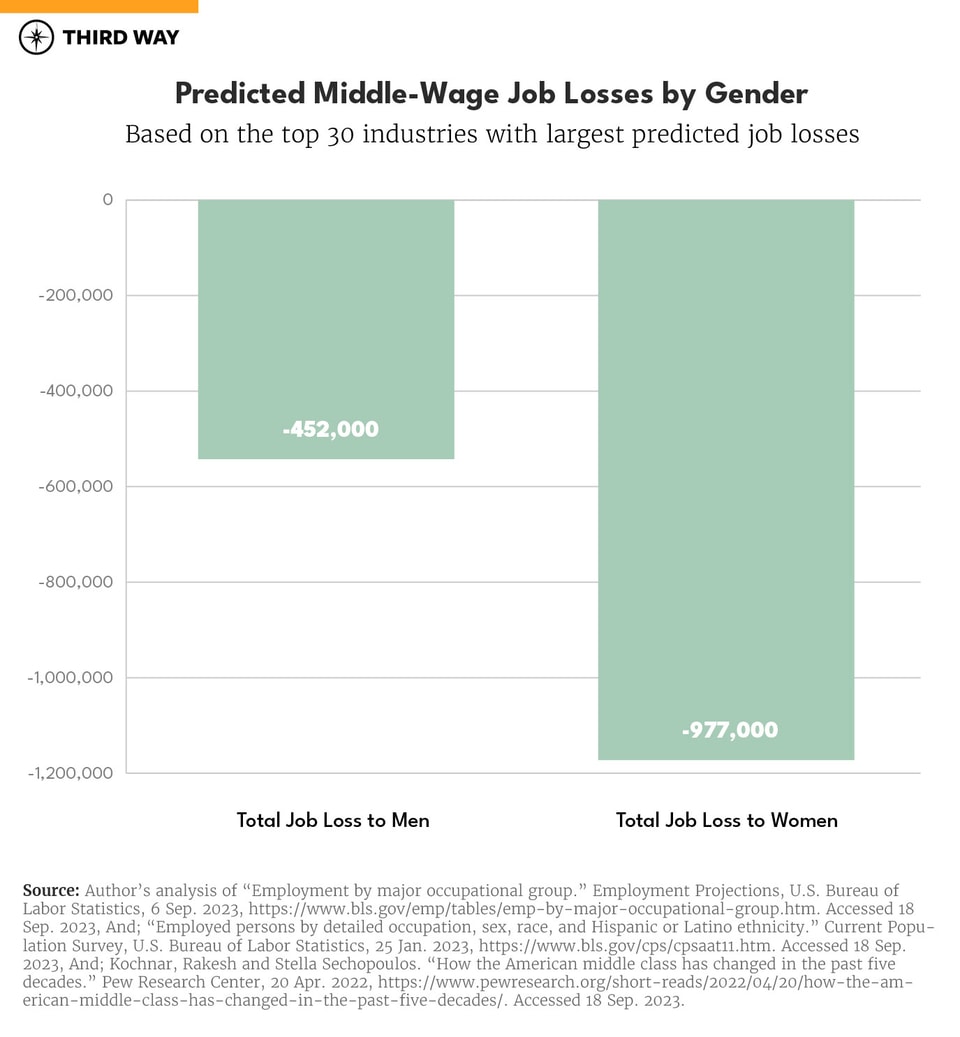

Non-college women are slated to lose the most middle-wage jobs.

Beyond employment declines, the decade ahead is especially bleak for middle-wage jobs—those paying between two-thirds and two times the median wage in the United States (approx. $36,700 to $110,100). Within the industries that will be most affected, women will account for 68% of middle-wage jobs lost.5 This will largely be driven by job reduction in office and administrative work—a field in which women without a degree have long found economic opportunity. These jobs typically offer good wages, benefits, and job security, all of which provided a dependable path into the middle-class for non-college women.

The predicted drops in office jobs come as automation and outsourcing reduce companies’ need for these employees to be in house. And many of the administrative roles that remain are now requiring workers to hold a college degree.6 As a result, non-college women have fewer available options for jobs that pay a good middle-class wage.

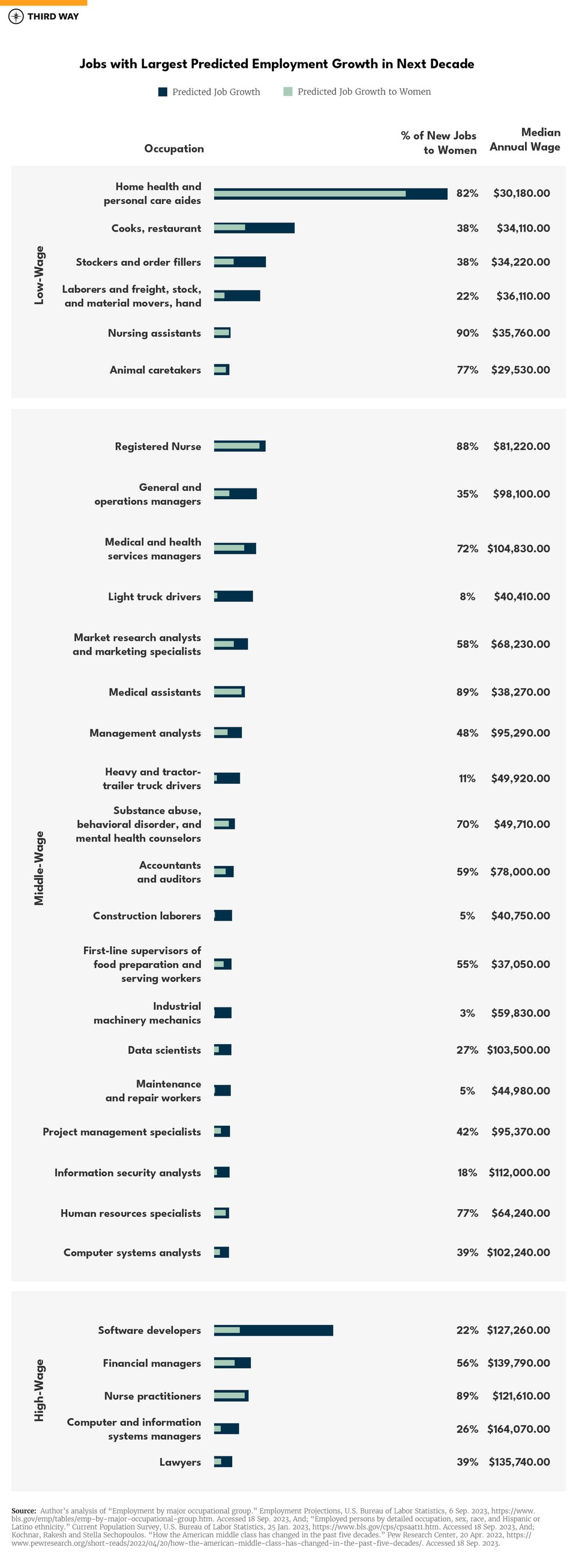

Job growth for non-college women will be concentrated in the lowest-paying sectors.

Job loss isn’t the whole story, though—BLS predicts a little over half of jobs created in the industries seeing the largest growth will go to women.7 But there’s a catch: half of those jobs will be in low-wage occupations that pay less than $36,700 per year, and just 15% will be in high-wage occupations that pay over $110,100 annually.8 Women will also be underrepresented in fast-growing middle-wage jobs that don’t require a college degree, only making up a majority of new workers in just two middle-wage non-college occupations— one of which being medical assistants, a job that requires a credential.910

With college workers expected to capture much of the growth in high-income jobs and as many middle-wage jobs continue to disappear, non-college workers get stuck with lower-paying work.11 This concentration of jobs at the high and low-income wage levels is a trend with troubling implications for all non-college workers but especially for women. They will bear the brunt of middle-wage job loss and see far less of the high-income job gains.

Conclusion

For non-college women, the decade ahead could be bleak. The predicted decline of office and administrative work will further erode their pathways to the middle-class as low-paying jobs take their place. Many of these new jobs will involve caring for others—work which continues to be central to the well-being of our society and economy—yet remains low-paying. Without efforts to increase the quality and pay of care-work jobs, as well as an investment in the skills needed for pathways to good middle-class jobs, non-college women will face further hurdles to economic security in the future.

But not all hope is lost—there are ways policymakers can help non-college women move into higher-paying fields while also boosting the quality of critical care jobs. Women represent just 13% of all registered apprentices, but the number of women in apprenticeship programs has more than doubled in the last 10 years.12 Continuing to boost female representation in apprenticeships—and in fields currently dominated by men—is essential to creating more opportunities for non-college women. Meanwhile, pandemic-era funding has helped many places across the country increase the wages of child care workers. And while funding is running out, there are many states committed to keeping these changes in place. These efforts provide an example for federal policymakers to make much-needed investments in our country’s care workforce.

Appendix