Memo Published October 9, 2025 · 17 minute read

AI and Emerging Technologies in Health Care

Mike Sexton

Takeaways

- AI and emerging technologies are transforming the shape of health care and creating new categories of regulatory concern.

- AI is simulating talk therapy, performing diagnostics, discovering drugs, documenting hospital stays, assisting with surgery, and helping couples conceive.

- In the coming decades, AI, biotech, and robotics have the potential to forge new forms of health care that may change human life at every stage, from conception to death.

- Lawmakers should embrace the potential for technology to improve and sustain human life but must impose guardrails as its borders become increasingly nebulous.

Cyberpunk novelist William Gibson famously remarked, “the future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed,” and nowhere is this truer than in health care technology.1 The current role of AI and emerging technologies in health care is profound: AI can already outperform doctors in many areas and together they are even more powerful in solving the toughest health care problems. The trajectory of this sector has the potential to redefine what patients can expect from care in the coming decades.

In this report, we unpack where AI is currently having an impact on health care and explore just some of the innovations treating mental and developmental disorders, physical care, and reproductive health. We then look at where AI has the potential to continue revolutionizing health care in the future and what policymakers should consider. The API Agenda—Advance, Protect, Implement—is a key framework for lawmakers to secure Americans from the novel risks these technologies pose without losing focus on the massive opportunities they offer to improve and enrich their lives.

Present

AI is already having a significant impact throughout the health care system. Below, we highlight different examples of where AI is influencing care today.

Mind

AI can currently diagnose many common disorders with accuracy of at least 83%—with some models scoring near-perfect in early testing—including ADHD, autism, depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.2 This innovation can have a profound impact on the standard of care provided to Americans if it continues to improve and is made accessible on a national level. Two especially important conditions where this technology can improve health care outcomes at scale are in early detection of autism and Alzheimer’s disease.

Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder estimated to occur in one in every 54 children.3 It is characterized by sensory processing issues, challenges with communication, special interests and hyperfixations, repetitive behaviors, and a variety of other cognitive and emotional differences.

Today, researchers have developed AI-based tools that can diagnose autism using a variety of methods, including neuroimaging (e.g., MRI/CT/PET scans), facial analysis and eye-tracking, and even behavioral data.4 Using these techniques to diagnose autism earlier can give parents and caretakers more time to tailor the educational, social, and home environments that are best suited to support autistic children’s individual development.

AI is also being used to help autistic people navigate social cues and nuances.5 A small humanoid robot named NAO has proven effective at helping very young children with autism learn to pay attention and respond in social interactions.6 An app called Goblin Tools—for users of all ages and neurotypes—offers simple AI tools that modify or interpret the emotion and tone of a text.7 Another app called Autistic Translator can process descriptions of social situations and explain nuances and cues the user may have missed.8

Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease, the leading form of dementia, is caused by the build-up of certain proteins in the brain. The patient’s memory and cognition decline as the proteins accumulate, which is why Alzheimer’s is known as a progressive disease—and why early diagnosis is so important.

Researchers have developed several AI-based solutions to diagnose Alzheimer’s based on neuroimaging, speech patterns, neuropsychological tests, or gene and protein biomarkers in blood.9 When deployed at scale, these tools allow earlier intervention—slowing progression and preserving patients' memories and relationships for longer.

Like for autism, there are many AI applications that can help manage Alzheimer’s and dementia. Google Arts & Culture has helped launch an initiative called Synthetic Memories, which uses the company’s state-of-the-art AI image and video generation to illustrate the memories of dementia patients, helping trigger more recollections.10 While this use case may be simple within today’s universe of generative AI applications, it is a revolution in the field of reminiscence therapy—a decades-old and evidence-based treatment for memory disorders.

Body

AI and other biomedical technologies have the potential to change medicine and care in transformative ways that can improve the lives of patients and practitioners alike—if they are implemented thoughtfully.

Automated Insulin Delivery

For diabetes patients who cannot reliably produce insulin, an insulin pump is a lifesaving but often onerous solution to manage blood sugar (aka glucose). Historically, insulin pump users have had to manually log when and how much carbohydrates they are eating so the pump can inject the proper amount of insulin.11 If they forget, lack of insulin spikes their blood sugar; if they overcorrect, too much insulin can drive blood sugar dangerously low.

Today all insulin pumps sold in the United States can integrate with a continuous glucose monitor to help avoid this. Automated insulin pumps like the iLet Bionic Pancreas go further, using algorithms to adjust insulin delivery throughout the day based on the patient’s blood sugar level. Studies show these systems improve blood sugar control, and many patients report that reduced day-to-day maintenance translates into a considerable quality of life improvement.12

AI Diagnostics and Ambient Documentation

Diagnostics and documentation are two structural chokepoints in the modern health care system. There are only so many providers with the necessary expertise to give a diagnosis, and the modern medical bureaucracy imposes staggering paperwork burdens on practitioners—a major contributor to the industry’s burnout crisis.13

AI can diagnose a long list of conditions with high accuracy—Google and partners have developed diagnostic systems for tuberculosis, anemia, and several forms of cancer.14 There are over 400 FDA-approved radiology AI products on the market, radically changing the workflows of the industry.15

AI is also poised to reduce the time medical providers spend on paperwork—which, for many, eclipses the time they spend on care.16 Today, doctors can dictate patient information to new AI systems that update the patient’s electronic health record automatically—a technology known as ambient documentation.17 Amazon Web Services has launched AWS HealthScribe, a cloud-based ambient documentation system designed to support Health Insurance Portability and Accessibility Act (HIPAA)-regulated workloads.

Coupled with advances in telemetry and patient monitoring—a physician remotely monitoring an outpatient’s heart rate from their smartwatch, for example—the medical field can soon exemplify how AI and emerging technologies can augment rather than replace work.18 These tools can also bring down costs and make health care more accessible. They will allow providers to spend more time on patient care and eliminate the need for time-intensive in-person visits for patients.

Robotic Surgery

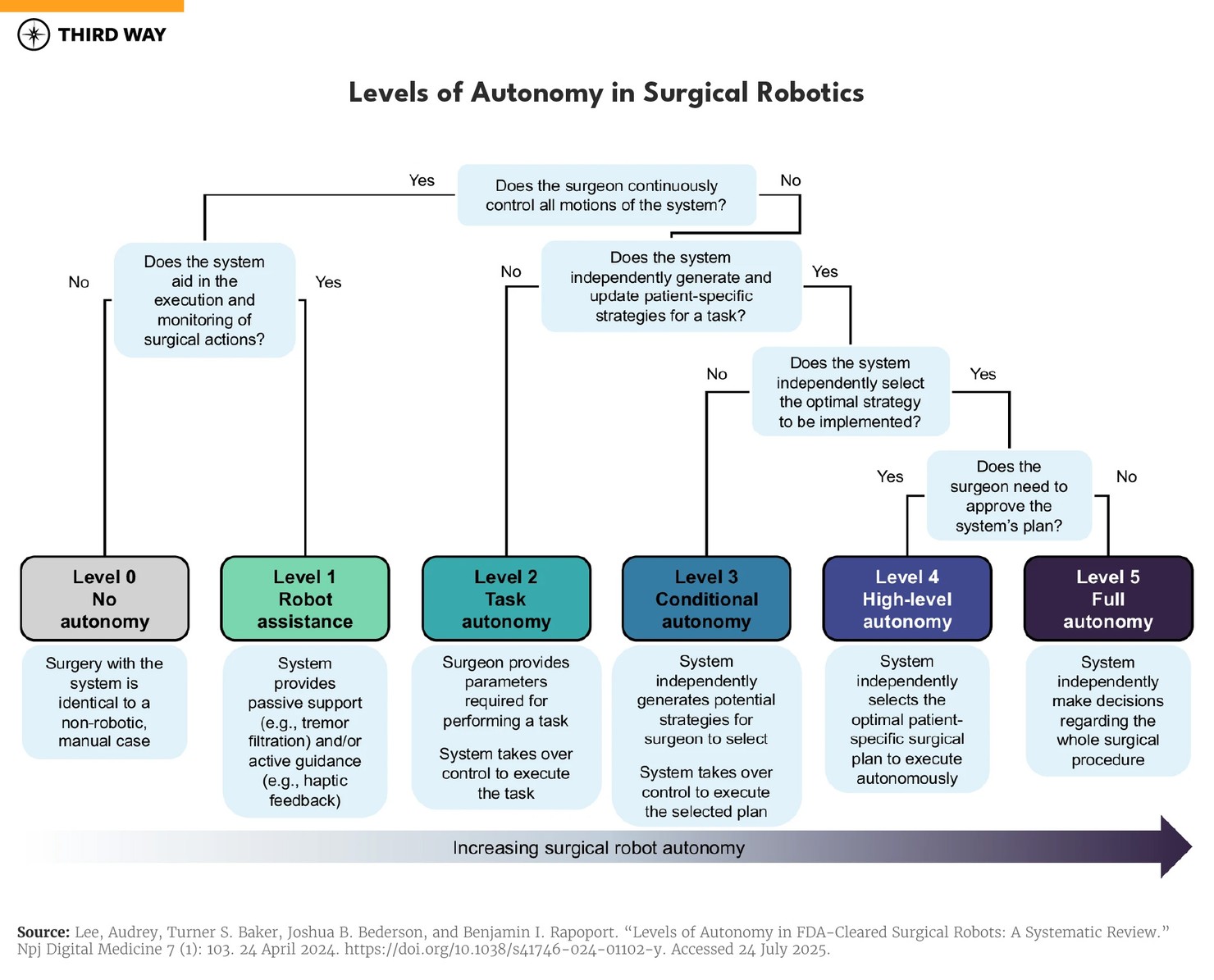

There are five levels of autonomy in surgical robotics, up to full autonomy with no surgeon in the loop (level 5). Today’s technology is at level 3—conditional autonomy—meaning surgical robots can provide the surgeon with strategies to complete an operation and execute tasks independently. The TSolution-One, developed by THINK Surgical, is an example: it assesses the patient, creates plans for a surgeon, and—with their approval—performs bone milling by itself.19

Surgical operations, however, are dangerous without human oversight. As surgical robotics advance—even as their error rates fall below those of humans—it is crucial that a human is accountable for what the autonomous system does. With current surgical robotics operating at level 3 autonomy, industry leaders and regulators must carefully study and preserve the oversight necessary for such systems to serve patients safely as the technology progresses.

AI-Enabled Drug Discovery

AI is revolutionizing the field of drug discovery, helping identify new chemical compounds that can treat disease. Food and Drug Administration applications for drugs with AI-discovered components have steadily increased over the last decade, exceeding 300 in 2024.20 Amazon Web Services (AWS), for example, has partnered with EvolutionaryScale to host ESM3—a family of language models that enable pharmaceutical customers to generate completely new proteins from scratch.21 AIs like ESM3 enable what scientists call “programmable biology,” a novel approach to pharmaceutical development that can reduce the time and costs to bring new medicines to market.

Isomorphic Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet, is preparing to begin human trials of AI-discovered drugs. With research collaborations with Novartis and Eli Lilly, Isomorphic Labs supports existing drug research and is designing its own medicine in oncology and immunology through a narrow superintelligent AI called AlphaFold.22

Google developed AlphaFold to predict the 3D structure of different proteins en masse—a process that used to require painstaking months or even years of study for a single protein.23 While artificial general intelligence (AGI) remains speculative, AlphaFold is a real-world example of narrow superintelligence—an AI system that outperforms the best human experts in a tightly defined domain. As policymakers debate the theory of AGI and its future impact on the economy, they must understand that narrow superintelligence like AlphaFold already exists, and its radical implications for fields like drug development are unfolding today.

Family

AI and emerging technologies are shaping the future of reproductive care, too. As fertility rates in the developed world continue falling, AI has the potential to help more families have healthy children.

Embryo Selection and Advanced Diagnostics

About a third of embryologists worldwide today use AI, with embryo selection cited as the most common use by far.24 One embryo selection program is BELA—the Blastocyst Evaluation Learning Algorithm—developed by Weill Cornell Medicine.25 BELA scores the viability of embryos with high accuracy, based on a training set of just 2,000 embryos. Coupled with other AI-based diagnostic systems, AI products like this result in a more efficient and effective IVF process for prospective parents.

Future

As Niels Bohr allegedly said, “it is very hard to predict, especially about the future.”26 There is no guarantee that many emerging technologies will necessarily mature enough to become useful. This is also true when considering emerging medical technologies on a timescale of decades. And yet, there is immense potential for AI to continue revolutionizing health care in the future.

While many of these applications remain hypothetical, they raise important ethical and regulatory questions for industry leaders and lawmakers.

Mind

The next frontier for mental health technology involves not just treating the mind but digitizing and interconnecting with it. As AI helps researchers break new ground in various scientific fields, its impact on neuroscience has the potential to be profound.

Brain-Computer Interfaces

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) read electrical signals directly from the brain, typically to control an external device or software like a cursor, keyboard, or robotic arm. The first tools to measure brain signals were developed in the 19th century; yet, a century and a half later, fewer than 100 people have ever had a BCI implanted.27

BCIs have enabled patients with paralysis to play video games, type emails, and even regain control of limbs through exoskeletons.28 While BCIs offer impressive latency, the brain signals they decode are relatively simple—enabling cursor control at speeds comparable to an able-bodied person but allowing only a fraction of that speed for speech or typing.29

Body

New technology is poised to improve our health significantly, but in the process may transform the medical practice irreversibly. As AI and biotechnology advance, regulators and health care providers must adapt to preserve humans’ role in health care.

Digital Twins & AI-Personalized Medicine

Digital twins are computer simulations of real-world objects or systems like a factory floor, city traffic, earth’s climate, or—one day—perhaps even the human body. Nvidia Omniverse is a digital twin platform, enabling manufacturers like BMW and Lockheed Martin to predict maintenance needs and optimize industrial processes.30 While the human body’s biology is trickier to simulate than the operations of an industrial facility, scientists are making progress organ by organ.

Researchers began attempting to simulate the human heart in the 1950s, paving the way for digital heart twins that are now better at predicting the risk of drugs causing arrhythmia than animal trials.31 In 2006, Korean scientists built the first computer model of a single woman’s entire 60,000-mile-long circulatory system.32 Today, efforts are underway to build digital twins of the liver, lungs, and even the brain.33 As AI and computing power improves, these digital twins can come closer to capturing the unimaginably complex interplay of the human body’s trillions of cells.

Medical digital twins can extend AI’s role in pharmaceutical development beyond the lab.34 While AI today is enabling researchers to create new candidate medicines, 80% of the cost of bringing a new drug to market occurs at the clinical stage.35 High-fidelity digital twins can accelerate this, allowing researchers to better discern which medicines are most promising with fewer and faster human trials.

Just as BMW uses digital twins to optimize their factory floors, researchers also hope one day doctors can use digital twins to provide personalized health care to patients.36 Prescriptions, for example, could be written not only based on trial studies, but on a simulation of the drug’s effects of the individual patient’s body. These systems along with AI generally can improve health care dramatically, but they are so advanced that doctors will struggle to scrutinize their guidance without new ways to hold AI systems accountable.37

Radical Life Extension

Life extension is a hot topic beyond the medical community—from the Netflix documentary Don’t Die to Peter Attia’s bestseller Outlive, many non-medical professionals are seeking to lengthen their lifespans beyond simply following their doctors’ advice.38 Radical life extension is the apex of this trend: the effort to not only avoid aging but to halt it entirely.

Futurist Ray Kurzweil projects that life extension in the 2020s will be driven by advances in AI-discovered drugs and AI-personalized medicine, while the 2030s will be defined by nanorobots injected into the bloodstream, capable of regulating the supply of “hormones, nutrients, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and toxins,” augmenting or even replacing organ functions.39

Medical nanorobots are an emerging scientific field and are typically made of or encapsulated within biological material like DNA or protein to survive within the body. In animal trials, scientists are already developing nanorobots capable of breaking up blood clots, detecting cancer, and even delivering precise chemotherapy with lesser side effects.40

It may be farfetched to imagine nanorobots extending our lifespans indefinitely, but they do have potential to revolutionize treatment of disease and improve quality of life.

Family

Future reproductive technology has breathtaking potential, tempered by the highest standards of caution in health science. Risky experimental treatments can be justified when there is no other way to save a patient’s life. But when creating life, the Hippocratic oath—“first, do no harm”—takes precedence. Industry leaders and regulators should take care to ensure that ethical and safety considerations are balanced with the tremendous potential of AI-powered reproductive tools.

Artificial Wombs

Artificial wombs sidestep the Hippocratic dilemma facing other speculative reproductive technologies: their immediate use is not to create new life but, instead, sustain premature babies. Scientists have developed artificial wombs (also called “biobags”) for premature lambs and pigs, so far weaning one lamb that has survived long-term.41 For extremely premature babies—born around 22 weeks—artificial wombs could considerably improve the outcomes of neonatal intensive care.42

In Vitro Gametogenesis (IVG)

In vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, refers to creating sperm or egg cells in a lab—an AI-intensive reproductive technology that, if demonstrated in humans, could help couples overcome infertility and may even allow gay couples to have biological children. It has been proven in mice that IVG is possible and can result in healthy offspring, but some variations are harder than others.43 The simplest form will be producing gametes that match the patient’s gender, which is why IVG startups like Conception pitch themselves as tackling infertility.44 Trickier is making eggs from a male—so far, this has only been achieved in mice.45 Hardest of all would be making female sperm, which has never been done for any mammal.46

IVG is likely to first benefit older or infertile couples, expanding access to parenting while introducing new risks for older mothers. It may then enable gay male couples to have biological children via a surrogate. So far, IVG has not yet produced viable sperm from female cells—but there is a separate, non-IVG method has successfully allowed two female mice to conceive healthy female offspring.47

Recommendations

In an earlier paper, we called on lawmakers to embrace a bold and opportunistic AI agenda built on three pillars: advance, protect, and implement. We argued that a multifaceted approach is critical to address pessimists’ anxieties, harness accelerating technological growth to benefit Americans, and appeal to the entrepreneurs and innovators who will make it possible.

That framework can also be used to navigate the opportunities and risks of AI in advanced health care and biotechnology. As technology advances at an unpredictable pace, lawmakers should adopt a balanced stance that aims to manage risk, reduce costs, support health care providers, and deliver better outcomes for Americans. Here’s how to do that:

Advance Transformational Science and Technology

- Fund research of AI systems that compares its effectiveness against existing medical care and other AI systems—especially in diagnostics, mental health, and early disease detection.48

- Expand National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation programs supporting biomedical AI, robotics, and personalized medicine research—including emerging areas like digital twins and nanorobotics.49

- Support digital infrastructure for scaling access, such as rural broadband for telemedicine, and cloud computing for rural and safety net providers.50

- Expand the US Department of Health and Human Services’ standards for making health care data and documentation fully interoperable between electronic health record systems, enabling patients and their providers to control the use of health data privately and securely while also furthering the use of non-personal health data for training AI systems.51

- Modernize US Food and Drug Administration protocols to keep pace with AI-assisted drug discovery pipelines and new forms of medical technology.52

Protect Patients, Privacy, and Human Dignity

- Include accountability standards for the use of robotic surgery, AI diagnostics, and other AI systems in existing accreditation standards for hospitals and licensing for health professionals.53

- Update health privacy laws to ensure new sources and forms of data like smartwatches, DNA, or BCIs are not surveilled or abused and improve security and enforcement of federal privacy laws.54

- Improve the rights of individuals and their families to control their genomes and digital likenesses in life and after death.55

- Update health insurance regulations to account for the introduction of AI-powered diagnostic tools and treatments. Regulations should ensure that patients who opt to use the tools do not face prohibitive costs. They should also protect patients from increased costs or reduced coverage options as a result of biased or incorrect conclusions from AI-powered tools.

Implement Technology for Real-World Impact

- Accelerate Medicare and Medicaid coverage of AI-enabled accessibility devices (e.g., smart glasses/headphones) under assistive tech coverage.56

- Test the effectiveness of giving practitioners in Medicaid and Medicare a bonus when they adopt AI-powered diagnostics, ambient documentation, and other emerging medical technologies.57

- Assign a single federal agency like the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality with the task of overseeing the collection of real-world evidence from the use of AI systems in clinical deployments to continuously improve implementation, support adoption, and reduce costs.58

- Provide coverage for fertility treatments, including IVF, through Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act’s definition of essential benefits.59

The future of health care and biotechnology is both dazzling and disorienting. To steer it wisely, lawmakers must lead with hope—not fear—and pursue a strategy that harmonizes innovation with accountability to deliver real results for the America