Transcript Published April 13, 2016 · Updated April 13, 2016 · 61 minute read

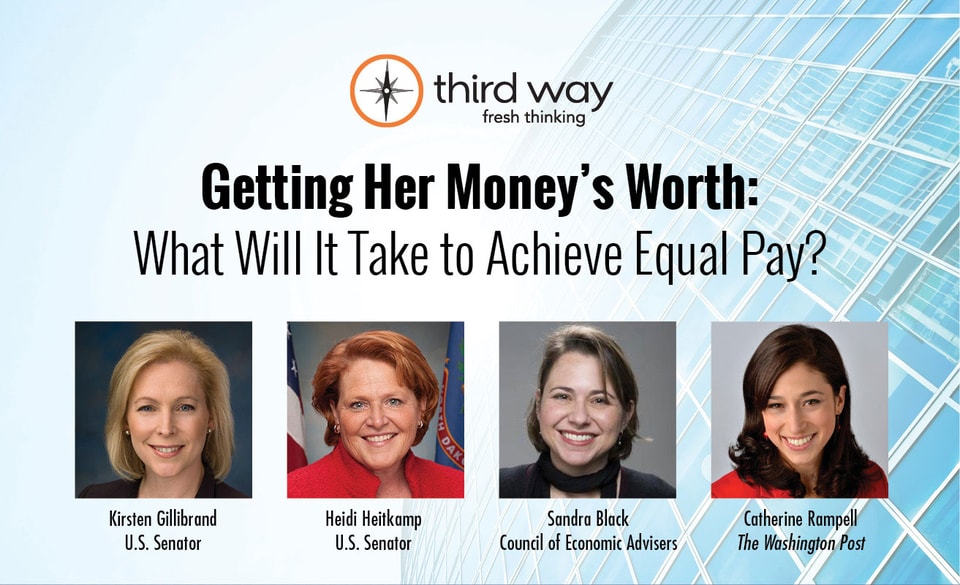

Getting Her Money's Worth: What Will It Take to Achieve Equal Pay?

Third Way

Getting Her Money's Worth: What Will It Take to Achieve Equal Pay?

Speakers:

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY)

Senator Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND)

Sandra Black,

Member, Council of Economic Advisers

Moderator:

Catherine Rampell,

Opinion Columnist, The Washington Post

Introduction:

Jim Kessler,

Senior Vice President for Policy, Third Way

Location: The McDermott Building, Washington, D.C.

Date: Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Transcript By

Superior Transcriptions LLC

www.superiortranscriptions.com

JIM KESSLER: So what I’m going to do is I’m going to introduce our guests, and then I’m going to get out of the way. And then after our panelists speak, we have Sandy Black from the Council of Economic Advisers, who’s got some great new numbers that we’re going to look at and continue the discussion.

So our first panel. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand. You may not recall this, Senator, but our first conversation occurred days after your appointment to the Senate. It was over some kerfuffle about something. We got on the phone, and you and I were both giving our kids a bath while we were on the phone. (Laughter.) So I thought that was appropriate for today’s discussion.

Senator Gillibrand is perhaps the leading congressional voice of the modern women’s movement. She’s fighting to get women off the sidelines and into boardrooms and into public office. She took on the United States military over sexual assault and misconduct, and won, and she is author of the leading legislation to address gender pay disparity in America.

My first encounter with Senator Heidi Heitkamp, there was no bathtub, but she did – (laughter) – do the almost impossible. When I heard her speak for the first time, I actually came away believing this absurd notion that a Democrat could win a Senate seat in North Dakota. And, of course, she did because she is simply amazing. She’s a leader on gender equity issues. She’s a common-sense centrist, a passionate leader of the moderate Senate Democrats who is admired.

She’s got a spine of steel and a heart of gold. And in the words of Senator Bob Corker, she’s stronger than battery acid. And he meant that as a compliment, which it is. (Laughter.)

SENATOR KIRSTEN GILLIBRAND (D-NY): Corker’s got a lot of phrases. He called me a honey badger, so – (laughter). Have you seen that video? It’s really funny.

- KESSLER: I have no –

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Look it up: Honey badger, YouTube.

- KESSLER: Yeah, that’s an interesting one. (Laughter.)

Catherine Rampell is part of – is a brilliant economist who can write, which is a rare commodity. She’s the leader of a modern generation of economic writers who meld opinion, hard data and insights into continually fascinating columns. She brings humor to her writing and deep insights. When she’s not writing about the Buffalo Jills or her wedding invitations or how women define themselves in their – or don’t define themselves – in their careers, she’s writing about perhaps a new emperor for America, a king, like Donald Trump, in her column today. She makes a very good argument that he’d be a great king. She founded – helped found the economics blog at the New York Times and now writes a must-read, twice-weekly column in The Post.

So we’re so pleased to have all of you. I am going to get out of the way so that you can have your discussion. Thank you. (Applause.)

CATHERINE RAMPELL: Thank you. Thank you so much, everyone, for coming, and for our esteemed panelists for being here.

I want to add an endorsement of “9 to 5,” which may feel like a dated movie, but if you watch it now, the ending of the movie is this, like, amazing feminist fantasy where they’ve instituted on-site nurseries and flexible work schedules, and productivity goes way up, and it’s just like the company’s doing better than ever and is more profitable than ever. So we can talk a little bit later on about what evidence there is for that happening in real life. There is potentially some. But anyway, good movie.

But for now, I wanted to actually open by talking a little bit about paid leave. Senator Gillibrand, as many of you may know, introduced legislation, the FAMILY Act, that would effectively grant paid family leave through a social insurance system to Americans not only for the parental-leave time period, but for other kinds of care.

And I wanted to talk with you, Senator Gillibrand, first about what we’ve learned so far from what states have done on this issue, as there are a number of states, including the state you represent, where I now live, New York, that have passed this legislation. New York hasn’t implemented it yet, but others have.

So what have we learned from states like California, that have already introduced a system like this? How does it inform what we should be doing at the federal level? And why not leave it to the states to begin with?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Well, if you waited to the states to do it, there’s a lot of people who won’t have access to paid leave for decades. So that’s not an option. But it is great that states are leading the way, because now we have a track record on which to make our arguments. And California’s a perfect example. California’s had it for 10 years. It’s a fairly modest program. It’s 50 percent of someone’s pay, which is better than nothing, and good employers enhance that by adding additional leave. They just increased it to 70 percent, so it’s a huge success for California to double down on it.

But the surveys done with businesses are great. Ninety percent of businesses said it had no negative effect or a positive effect on their bottom line; it’s at 87 percent said it had no effect on their operating costs; 99 percent said it had an increase in morale. So it’s a really value-add for California businesses, and they’ve had 10 years to test it out and they know it works.

So that’s helpful. And so New York just passed their own paid leave plan, which is great, which will get up to about 66 percent of someone’s pay. And it just matters.

And so the national plan we’re trying to do is to create a state-of-the-art plan where all employees, no matter what industry, large company, small company, part-time or full-time, you would get 66 percent of your pay over 12 weeks, with a cap. It can get up to $4,000 a month. And that would make a huge difference because if you’re an employee who has two or three jobs, you’re part of the gig economy, you’re buying into it your whole life. And people take it when they need it because every person – every person – is going to have a family emergency. Either your mother is going to get sick, is dying with cancer and you need to be by her side, or you have a new baby, or your spouse gets sick and you need to support him or her. It makes a huge difference to have it available.

And when I talk to upstate businesses in the more conservative parts of my state – it’s only $1.50 a week. So I say, would you buy each employee one cup of coffee a week so that when something happens in their life, they can take leave? And they overwhelmingly say, of course I would, that’s not a lot of money, it’s less than $100 a year per employee.

And so the employee puts in, the employer matches it, and that’s how you have a social insurance plan that will be there for all workers when they need it.

- RAMPELL: Senator Heitkamp, have you talked with employers in your state about this? I imagine that employers in North Dakota might have a different view of what they might perceive as a mandate.

SENATOR HEIDI HEITKAMP (D-ND): I think the first thing that I want to ask of this audience is, how many of you have paid leave? Raise your hand.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: That’s so bad.

- RAMPELL: Not great.

SEN. HEITKAMP: Not great. I mean, because everybody seems to think that this is maybe states like North Dakota, that are red states. Not necessarily. This is a challenge that so many families have. And so we can’t – we can go through the economics, as Kirsten just did, and talk about how this is going to actually help businesses. We can do the comparisons, like I like to do, with unemployment insurance, which now you can imagine what a fight that was when we first talked about it, but now we know that it gives families that security that they need when bad things happen economically to them. This is when bad things happen health-wise to families, they need some additional security. And in my state, less than 50 percent of all the people in my state do not have one day of paid leave, medical leave.

And so when you look at the impact that that has economically and you begin to talk about this, and you get beyond the kind of visceral reaction people in my state have to another government program, and you talk about the experience of California and you talk about Minnesota’s going to do it – and I raise this issue with my businesses. The single most difficult issue we have in my state is recruiting workforce. We have too many jobs and not enough people to fill them. And I say, if Minnesota does this and offers this benefit that becomes, you know, embedded in the social fabric of what they do in Minnesota, do you think you’re going to keep kids in North Dakota who could work in Minnesota? And that’s our competition.

So I talk about this from the standpoint of competition for labor, which is going to become a bigger issue than what it’s been in periods of high unemployment. And so in North Dakota we always have low unemployment because if people are unemployed they don’t stay in my state, but now we have less than 3 percent unemployment. If we’re going to keep a workforce, we need to look at benefits. Small businesses can’t do this. They can’t just provide the benefit; it’s too expensive. We met with a small-businessman in my state who runs a great little variety store. It’s Hip and Happening, downtown Fargo. I know you might not believe anything hip and happening happens in downtown Fargo. (Laughter.) I think Kirsten can –

SEN. GILLIBRAND: It was an awesome store. (Laughter.)

SEN. HEITKAMP: But he said, I cannot afford this benefit, but if I could join a bigger pool, just like we mitigate risk in everything that we do – whether it is, you know, insurance, health insurance, or whether it’s unemployment insurance, whether it’s workforce safety insurance – we know how to mitigate risk for small businesses. This is risk mitigation for small businesses, to avoid disruption.

- RAMPELL: So he didn’t – the other objection I could see employers having to an insurance program like this is that it encourages workers, whether men or women, to take time off. Even if the cost of paying for those lost wages isn’t borne directly by the employer, it still means that they have to find a replacement, right, if people don’t have the option of taking time off.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: But the cost to replace a worker is so much higher. So a temp worker –

- RAMPELL: Finding a temporary worker.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: A temp worker is easy. You can find a temp worker. But if you’ve trained this woman for five years, 10 years – she’s going to need time to have that baby. Nobody goes back to work the day after they have a baby, so she’s going to have to quit. And if she has to quit because she has no vacation days or sick days, you have to find a replacement worker. Over the last 10 years, businesses have spent $3.3 billion on replacement workers alone because of the absence of paid leave. So it costs them a lost more.

And when you talk to an owner about how much they value their employees, they want to keep their employees. And so when this life event happens, they want to be able to accommodate them; they just can’t afford to. They would love to let that new child have their mom around for a month or two or three, or they’d love to have that friend who – that worker whose husband’s sick to be able to be by his side, but they can’t afford it. So this allows them to afford it because they don’t have to pay two salaries.

- RAMPELL: I also wonder if it’s a bit limiting to think just about the sudden life events, like the birth of a child or a sick relative. I mean, there are other issues that, if you look at survey data and anecdotally with workers that I speak with fairly regularly, what they talk about are the lack of flexible hours, in general, right? So it’s not just like when a major event happens, but it’s day to day, how do you balance work and family life.

A lot of other rich countries have tried to create incentives or, in some cases, mandates for employers to allow flexible work schedules, to allow people to take part-time leave. Is that an appropriate step that you think the United States should consider?

SEN. HEITKAMP: I think a lot of that’s going to be driven by the marketplace. I just did a hearing this morning in my subcommittee which involves the federal workforce, talking about why it is that we sometimes can recruit millennials into the federal workforce but we can’t keep them. And we talk about flexibility and we talk about changing the dynamic of the workforce. The new entrants into the workforce are going to drive this agenda of flexibility, this agenda that’s not top-down management, collaborative management. You know, they’re going to recreate and refashion the workplace.

Now, that’s an organic process that’s going to take place over time. But if you are going to recruit the best and brightest in America today, you better be thinking about flexibility. You better be thinking about responding to the workforce concerns. Unfortunately, the federal government has this heavy bureaucracy that just seems immovable when you’re talking about 22 million applications to work for the federal government a year. Think about going through that. And how do you then organically build a better workplace that’s going to attract the best and brightest workers?

And so I think you’re going to see this happen without mandates because, as the new generation moves into the workplace, they’re going to drive the forces forward that are going to change.

- RAMPELL: Senator Gillibrand, do you think that there’s a role for government to play in either encouraging or mandating more flexible work schedules?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: You can’t mandate it, but you certainly could encourage it and you could incentivize it. And so you can give tax benefits. I had a bill, for example, to encourage employers to have on-site daycare or to at least create a daycare plan so that more workers had access to affordable daycare. I can tell you, you know, if you know where your child is and you could see your child during the day – I remember when I was nursing, because the House had a daycare, it was only a five-minute drive, I could go over and nurse three times a day because my schedule accommodated it. How many workers in America have that flexibility? They just don’t.

And so we need to incentivize employers to be the best employers, and make the business case that this is how you keep the best employees. And I can tell you the best employers are doing it. So the Googles and the Facebooks of the world that are desperate to keep their female workers, they’re figuring out. They’re figuring out we need to be able to accommodate young mothers with nursing, we need to be able to accommodate flexible hours, we need to be able to accommodate family needs. And so the marketplace will ultimately dictate. The best companies will have the best policies to retain the best workers. And we as legislators can elevate the issue so they can know these are best practices, and you’re not doing them, and you’re going to lose some of your best and brightest because of it.

- RAMPELL: So another question that I think a lot of economists worry about – economists and others – is, how do you avoid having more generous leave policies or more generous flexibility plans, whether they’re encouraged or mandated, from unintentionally penalizing female workers? So in a lot of other rich countries where they do have very generous family leave policies or, you know, a requirement that employers have to consider a part-time work request, et cetera, there are many more women in the workforce but they’re much more likely to be working part-time, they’re much less likely to be in management-type jobs, they’re more likely to be in those sort of traditional pink-collar jobs.

You know, there’s much more gender segregation because it’s believed that employers sort on the front end; that women are more likely to take the leave, so employers are less likely to hire them, or at least less likely to hire them into jobs that would be difficult to allow those kinds of arrangements.

Do you think about those kinds of trade-offs? You know, how do you make life easier for women but, to the extent that that also makes women more expensive to hire, how do you avoid having them be penalized by employers?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Is your mic –

SEN. HEITKAMP: I think it – is my mic on now?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: I think it is. You’re projecting –

SEN. HEITKAMP: Is it on? (Electronic feedback.) Yes. That’s somebody else’s fault. (Laughter.) This is pretty hot. Maybe I’ll just – (laughter). How about if I just do this? (Holding mic in her hand.) That makes more sense.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Yes.

SEN. HEITKAMP: You know, if you take a look at kind of where we kind of start out from the standpoint of providing flexibility because moms want to be moms and we want to be able to be great daughters, and we want to do the things that we think actually add value to our life beyond a career, and then you go, but won’t you be sacrificing your career, the dirty, little secret in America is you can’t have it all, you know. And I think that one of the things – the speeches that I give, is when people ask me, should I run for office, I want to be a mom, I want to do this, I want to do that, I say, you can’t have it all. Sometimes there needs to be a prioritization.

But that doesn’t mean that we should tolerate a workplace that doesn’t give you access back to the workplace – as Kirsten calls it, the sticky floor and the glass ceiling – doesn’t mean that we should penalize moms and that we should penalize good daughters. It means that sometimes we’re going to have to put our life on pause to do the things that we value or that are important to us in a different fashion.

And what I think is going to happen eventually in the workforce is this isn’t going to be a gender issue; this is going to be a workforce issue that’s going to involve dads and it’s going to involve sons, and that it’s not just going to be that gender identification with these are your roles and you’re going to fulfill these roles. I think we’re going to see more entrants into that kind of – you know, you mention Mr. Mom? Well, that was a whole story about a man in a role reversal, and I think you’re going to see that more and more as our society becomes more and more accepting of gender-neutral roles in America.

But I don’t think we’re there yet. I think for my generation, this idea of being the sandwich generation – you know, we’re taking care of our kids, putting them through college, and we’re also taking care of our moms – I can tell you with a great deal of certainty that the role of taking care of my elderly mother has not fallen on my brothers; it has fallen on me and my sisters, me less so, but, you know, that’s just where we are right now. Eventually I think you’ll see those gender lines being blurred, but again, it’s an organic process.

But anyone here who thinks that I’m telling you you can have it all, I think that’s unrealistic. You’ve got to prioritize in your life.

- RAMPELL: So, Senator Gillibrand, another way of asking about the issues that I was trying to raise is, are there ways that we could encourage either men to take more active roles in terms of caregiving, whether it’s to children or to other family members, and/or to encourage employers to be accepting of those roles? Like, if you look at survey data, men actually report having more work/life tensions than women do, perhaps in part because employers are more accepting of their female employees taking time off than their male employees.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Well, I think you can start with gender-neutral policies, so if you had paid leave, for example, on a gender-neutral basis and any worker could take it for any life event, and it becomes more acceptable for men to take leave for caregiving. Now, but you have to recognize – and I think this is part of what Heidi was saying – women are often natural caregivers. We often want to take care of our loved ones. We often want to be able to be there for our elderly mothers or be there for our kids. But you have to be able to sustain their opportunity in the workforce, so that’s why leave is so important. If someone in your family is in a hospital bed and dying and you want to be by their side, what has to happen is you have to have the flexibility to leave but then come back and not lose your place in that company, and be able to pay your bills during that time.

So that’s why I think having paid leave as a priority is going to create more opportunity for men and women to reach their full earning potential and not actually have to quit the job; I mean, because I can tell you, you know, one of my former employees, who’s now running for Congress, Colleen Deacon, she’s amazing, but when she was a young woman she was a waitress and she earned the minimum wage. She had no sick days and no vacation days. So when she got pregnant, she couldn’t accommodate the birth of the child because there were no days you can take off. You need to be at work tomorrow. So she had to quit.

She went on Medicaid. She had WIC for food supplements for her baby and for her. And then she had to start over in a new job three months later earning the minimum wage, losing her seniority, using whatever rungs she had walked up. That’s the sticky floor. So there’s no way for her to keep moving ahead in that company where she’s earned some seniority and experience.

And so I think if you change that one dynamic, you are going to have far more women earning their full potential, which also will change discrimination. We don’t have equal pay for equal work; you have to work on that, as well. You don’t have affordable daycare; huge impediment for young workers who don’t earn enough to pay for daycare. We don’t have universal pre-K; that’s a whole year you are out of the workforce where you could be. So these are basic – and you don’t have a living minimum wage. And so if you can’t even earn above the poverty line working 40 hours a week, that’s not the picture of the American dream that you and I know.

So you need the structural changes so women can compete better and earn their full potential and reach their full potential in the workplace, and make it more acceptable for men to take those responsibilities.

- RAMPELL: So there are some countries, as you may know, that have instituted, like, a daddy-leave quota; you know, to try to incentivize more fathers to take time off at the birth of their child and to also destigmatize it, I guess, amongst their employers, the idea being that it’s not completely gender-neutral but there is time off that is only available to fathers, or that if the father takes time off, the mother gets more time off. Do you think that that would be worth considering here? If that’s something you could talk to?

SEN. HEITKAMP: Yeah. I mean, I think that all of these things are the great experiments that are out there economically. And the question is, do we have a culture that supports gender roles equalizing? And the answer is, today we don’t. I mean, I think that’s being honest. I don’t think men see themselves as people who would take a lot of time off to care for, you know, a newborn baby; that’s something that their wives would do. They hope their wives can re-enter into the workforce at a level.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: But I do think that it’s changing generationally.

SEN. HEITKAMP: I do. I do. And that’s my point. I don’t know that—

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Twenty-somethings have a different view than our age.

SEN. HEITKAMP: I mean, I think you can incentivize these things, but I think at the end of the day, that new generation of male leaders who are much more engaged with their families – I tell a story. When I ran in 2000 for governor, my kids were 10 and 12, or 14. And people would ask me, how old are your kids? And if they asked it that way, I would say, well, they’re 10 and 14. Or they would say, how old ARE your kids? (In a different tone of voice. ) There was a big bubble: “Heidi Heitkamp’s a bad mother.” Right? “Abandoning her kids.”

When they asked me that, I would say, they’re same age as my opponent John Hoeven’s children. (Laughter.) And people, like, physically would recoil from me because they would never have asked him the question with that tone. They would never have assumed that he had an obligation that he was abandoning; he was just going to be the leader of the state because he was gender, you know, identified that way.

And so I think it’s really important that we lead with good policies, that we lead with good incentives, but that we recognize the cultural impediments that we have.

And I want to mention something because this, for me, is a critical piece of this problem. I want you to think about being a certified nurse assistant. Do you all know what CNAs do? Like the hardest work done in America is done by CNAs. They take care of our elderly. And they aren’t the ones just administering the shots. They’re doing the hygiene. They’re doing all of the very difficult physical work. They have the highest category of workers with back injuries. They have a lot of workplace stress. They’re dealing with very difficult patients They’re paid among the lowest people in America, for some of the hardest work.

And so when people say, well, of course, you know, there’s going to be disparities because all of these jobs in construction, that’s hard work, that’s physical labor, your time in construction is limited, I like to say, what about the CNA? And when Janet Yellen was in front of the Banking Committee, one senator asked her a question about income disparity. And they said, oh, well, we need to retrain and retool the new workforce, and that’s going to get us income equality. And when it got to me, I said, a CNA is pretty highly trained; why aren’t you paying her what she’s worth? Because we don’t value that work in America. That’s the bottom line.

- RAMPELL: So the corollary question to that is, if to some extent and to a large extent the pay gap is determined in part by the kinds of occupational choices men versus women make, is there a role for policy to incentivize women to go into more lucrative careers, whether change their college major or go into – you know, it doesn’t even need to be college educated, but to go into other training?

SEN. HEITKAMP: I have to tell you, I just so resist that because it somehow doesn’t fix the fundamental baseline problem, which is, we don’t pay women who work hard, enough. We simply say, well, then you should want to become a roofer, because if you go on the roof, then you’re going to make – that’s how I pronounce that word, I’m sorry. (Laughter.) If you’re shingling, you know, you’re going to get $10 more an hour.

Well, you know, I want somebody really highly qualified to help take care of my mom. I mean, so I think I resist this idea, let’s get them into STEM education. I think that that’s, like, the cop-out – better training, move them into other occupations – because fundamentally, as a woman told me this when I was running for governor, she said: My boyfriend works construction, and I work as a CNA in a nursing home. Can you tell me why people who help people, who are in the occupations that I am, get paid so much less than people who, you know, dig ditches?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Well, daycare workers don’t even get the minimum wage.

SEN. HEITKAMP: Sure. Well, and that’s one of the problems for providing daycare.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Yeah. So it’s a problem.

SEN. HEITKAMP: You don’t have workers.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: So I have a complementary answer to that. So, yes, I agree that you can’t make women not do professions that they want to do. You want them to do whatever they want to do, but we should pay them more. And caregiving – it goes to, unfortunately, a broader problem that we don’t value women in society, period.

- RAMPELL: But what are the policy levers we have?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: But let’s look. So we don’t value women in society, period, and that is shown in many ways. It’s shown in how women are portrayed in the media. It’s shown in we don’t have equal pay for equal work. It’s shown in women-dominant industries paid less. It’s shown that, when men and women work in the same industry, they’re still paid less, even in a woman-dominated industry. So if you say, well, what about nursing, are men and women paid the same? No. Male nurses are paid more. Let’s look at teaching. That’s clearly a woman-dominated – are men and women paid the same? No, men are paid more. So the lack of equality even within a profession is a huge problem.

So we have to fight these structural problems where we can, and then also make sure women and minorities are eligible for some of the highest-paid professions by not leaving them out when it comes to math and science when they’re young. And that’s a huge issue. You have to actually notice kids in the kindergarten class and the grade-school class, young girls, minorities, and say, you know, you’re actually good at math. Let’s talk about what you could do if you’re a mathematician.

And this is another studied issue. If you label a course at Harvard, “Water Infrastructure in At-Risk Nations,” 70 percent of the class is men. If you label it, “Community Creation of Health and Well-being and Happy Living,” 70 percent female. It’s the same course. (Laughter.) So you have to attract women where they are, that if you go into math, science, engineering, you can actually help people, you can change the world, you can meet people’s needs, because that’s often what women want to do. They want to make the world a better place. And so you can actually encourage them by reaching into the grade schools, lower grades, through inspiring them to actually be great in these industries so that they’re eligible for the fastest-growing industries with the highest-paying jobs.

SEN. HEITKAMP: I have just one point of illustration that someone once gave me. They said, if you have a newborn and they’re in the hospital and it’s a girl, you know, people don’t think much if you put her in blue and take her home. Right? You know, it’s no big deal. If you put a young – a newborn infant male in pink and take him home, think about just even at that very early stages how we differentiate value to gender. I mean, no one puts their newborn baby boy in pink, but we think nothing about putting our newborn baby girl in blue. And I think that’s true today even though that illustration was given to me 20 years ago.

- RAMPELL: I think we are now opening the floor to questions. Is there a mic floating around?

- : No. We can have people raise their hands.

- RAMPELL: OK, so just raise your hands and I’ll call on you. Any questions? (Pause.) No one?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Come on, don’t be shy. (Pause.)

SEN. HEITKAMP: Look at them. They’re like – (laughter).

- RAMPELL: I can keep going.

SEN. HEITKAMP: Well, I’m curious. How many of you believe that in your lifetime, we will have closed the pay gap and will have created, you know, the utopia of “9 to 5”? At the end of your work life, do you think those will be the conditions you’re working in? (Show of hands from the audience.) That’s really interesting.

- RAMPELL: It probably also depends on how you define closing the pay gap. I mean, to the extent that the pay gap is also accounted for by women taking more time off than men, for example, to raise children, and losing earnings that way, is that counted as part of the pay gap or is that not, you know?

SEN. HEITKAMP: Well, it does to me.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: If we have paid leave, they wouldn’t be losing money. That’s why you need paid leave.

- RAMPELL: But I mean in terms of when they return from paid leave, they’re on a lower trajectory.

SEN. HEITKAMP: So let –

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Why do they have to be on a lower trajectory? I don’t get that.

SEN. HEITKAMP: They don’t.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: They shouldn’t have to be. So when I take three weeks off from voting in Congress because I just had my second child, I shouldn’t be paid less and I should not have a lower trajectory. It’s just a part of being a human being and being part of this planet that we have children!

- RAMPELL: But a lot of parents take more than that off.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Whatever it is. If it’s three months, that’s still a legitimate amount of time.

SEN. HEITKAMP: Can I ask the question this way? How many of you thought that if 50 percent of the state legislatures and 50 percent of Congress were women, we’d see more progress made in pay equity? (Raises hand.)

(Show of hands from the audience.)

SEN. GILLIBRAND: (Raises hand.) Yes! (Laughter, laughs.) Without a doubt.

SEN. HEITKAMP: It’s about leadership, isn’t it? And it’s about shared example.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Totally about leadership.

- RAMPELL: So a question related to that that I wanted to ask is that, if you look at polling on these kinds of issues, on paid leave, for example, it’s very popular amongst both Democrats and Republicans, and yet Republican politicians are not so supportive. What do you think accounts for that? What do you think could sway those in the other party, considering that their constituents are supportive?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: I don’t know. Constituents need to speak up more, and we need to talk about how this affects regular people. But Heidi and I have talked about this. The biggest problem in Washington is not the lack of bipartisanship or the partisan bickering. The biggest problem in Washington is the lack of empathy.

And too many members of Congress are so wealthy, in a bubble, have endless caregivers when they need them, and do not appreciate what most working families go through in society. And that is their biggest problem. So they don’t see the problem. Oh, I didn’t need paid leave; my wife stays home. Or, I didn’t need paid leave, because we have plenty of money. Or, what does that look like; I’ve never been to a – I mean, honestly, they just don’t live the lives that most Americans live.

And so we need more women speaking out demanding action in red states and really holding these members accountable. One of the reasons why Heidi and I are talking about paid leave across the country is this should be something that every American citizen has a right to because the rest of the world always does it! We’re the only country that doesn’t, us and Papua New Guinea.

So we should be better. We should be understanding. It’s a drag on the economy. Women earn $320,000 less in their lifetime because there’s no paid leave, in both pay and retirement. Men lose $280,000. So you think about that untapped income that could be invested in our economy. It’s just an artificial drag that we should be addressing.

- RAMPELL: What about – oh, we have a question right here.

Q: So we know that the Europeans have – I’m just trying to do a comparison with similar countries. They have paid (work ?) leave. I don’t know about the differences in pay between men and women, but I do know that women are less likely to – (off mic) – positions in European countries. But if you could shed any light on the equity issues –

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Well, there’s a lot of gender bias in Europe, which goes to the question you asked earlier. And I don’t know if this statistic is still true, but the last time I read about it, Germany didn’t have daycare. So they expect that woman to not only take their leave, but stay home for two years, if not three or four. So there’s a difference in view of what is a woman’s role in society, and they don’t imagine her as having a career on the same level as men.

So there’s bias throughout cultures in Europe despite the fact that they believe in paid leave. And I just think we should allow women and men to make their own choices about what their careers look like and to be able to support their families in those choices. And that’s why paid leave is so important.

- RAMPELL: And a question right here.

Q: Hi. Thanks very much for being here today. I am a single female with no intention of having children or necessarily getting married. And I notice that immediately when we talk about equal pay, the conversation immediately shifts to women’s role as caregivers, which statistically is more true of women than men to have greater caregiving responsibilities.

So I wonder sort of how you bring women who don’t have caregiving responsibilities over and beyond those of the average man into the conversation about equal pay, because it sort of feels as though they’re being left out a little bit. So what are some of the policy solutions? Is that pay transparency and so on, that means you can speak to sort of the younger generation that may either be delaying those choices or not making the same choices at all?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Well, caregiving is beyond parenting, just so you know. I mean, I don’t know if your parents are still alive, but given Heidi’s example, that often falls to daughters, not sons. And it might be something you actually want to do; it’s not necessarily something that is forced on you, because of the nature that a lot of women have.

But equal pay for equal work affects all women, and it affects all women in all industries. I think there is only one industry where women make more than men. I wonder if anybody can guess what it is.

Q: Stock clerk.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: I don’t think so.

Q: Pharmacy?

SEN. GILLIBRAND: No. It’s therapy. So your therapist is valued more because she’s probably a better listener. (Laughter.) So – yeah, that’s it. So I think single women are vitally important in this conversation because equal pay for equal work is something that will affect them their whole lives. That’s one of the reasons why women’s conferences also focus a lot on mentorship and sponsorship and trying to allow women to reach their full potential, because sometimes we are our own number-one self-doubters.

And this statistic is relevant. You know, in their first job interview, women will negotiate their first salaries 7 percent of the time, but men will negotiate their first salaries 57 percent of the time. So on the first day of their new job, there’s pay inequality because women and men look at that first job opportunity differently.

But it doesn’t mean the women are wrong. And this is a really important point. Women have enormous emotional intelligence, and they will often perceive, if I play hardball on my salary, if I make waves on my first day, I not only will be considered an unhelpful or an employee that is not well-liked, I will be seen as a troublemaker or rocking the boat; whereas that male will be perceived exactly the opposite. He’s a go-getter, he’s a hard-charger; we want him. And the studies bear that out, that the perception of women asking for more money is often not well-received.

And so we have a structural bias about how the world looks at women versus men, and in this country specifically, that we come back to. And that means changing roles. It means changing how women are portrayed in the media. Again, having more men and women mentor those women so that they know when to ask for the raise, how to ask for the raise, how to get ahead in the company, because they need that extra encouragement and support because oftentimes we are our own self-doubters.

So I think it has to be a society approach to getting equal pay to where it needs to be.

SEN. HEITKAMP: I think it’s critically important that we not identify this as a woman’s issue.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Right.

SEN. HEITKAMP: You know, if you take a look at the quality of secondary and higher education, elementary education, you may never have a child, but you better be concerned about the quality of education in this country. You have to be concerned about the availability of the workforce to the best and brightest. And so, you know, just as we will talk about these from the empathetic standpoint, I like to talk about it from the economic standpoint. And as a single woman who has – you know, who at this point doesn’t have – hasn’t made that choice, I would tell you you need to be concerned about this because the condition of all of us elevates the – when we improve the condition of all of us, we elevate the condition for the entire society.

And that’s one of the things we’re going through in this election, is trying to figure out, you know, the top-down policy, but the anger is coming from the bottom. And it’s coming because these issues aren’t getting addressed. The challenges of working families are not getting addressed. The challenges of access to career opportunities are not getting addressed. And as a result, people are angry and they’re looking for, you know, a different paradigm. And that’s a failure that we’ve had politically to address real life issues, not just from an empathetic standpoint but from an economic standpoint.

- RAMPELL: I think we need to wrap up now so that we can move on to our next panel. But thank you so much to both of the senators.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Thank you.

SEN. HEITKAMP: Thank you.

SEN. GILLIBRAND: Thank you for having us. (Applause.)

(Pause.)

- KESSLER: Thank you. You know, there’s a huge gap in educational attainment, that men are – women are defeating men by a three-to-two margin. And you think of educational attainment and salary being hand in hand, but again this stubborn gap persists.

Our next guest, very excited, is from the Council of Economic Advisers, Sandy Black. She’s an economist. She has written and researched on gender equity issues throughout her career, both at the University of Texas, at the New York Fed, and also, of course, at the White House.

She put together a presentation, actually, just for us, which I think is incredibly generous, and that’s why we love CEA and their economists. So Sandy’s going to run through it, and then Catherine’s going to come back up and pose some questions. So thank you so much. Thank you for joining us.

SANDRA BLACK: So thank you for having me. It’s exciting to be here.

What I want to talk about today is present a few statistics for you to give you some of the background on the gender pay gap, and then talk about kind of some of the patterns that we’ve seen over time and how you should think about it, and kind of what the factors are that we think are underlying the disparities that we observe.

So just to give you the top-line number, in 2014 the median earnings of a woman working full time for a full year in the United States was 79 percent of the median earnings of a man working full-time for a full year. In the 1980s and 1990s, the gender pay gap closed a lot, and so over that time period, about 17 percentage points. After that time, it flattened out, so since 2000 it’s flattened out. And more recently, we’ve made modest progress, and here is a picture of that, with the gap closing by 1.8 percentage point from 2012 to 2013, and by an additional percentage point between 2013 and 2014. So you can see very flat up until the late 1970s; huge improvements in terms of women’s progress to about 2000; a flattening out; and then kind of an uptick now.

So if you break this down further, you’ll see that there are disparities by race. So by looking just at the overall number, you’re masking some of what’s going on. The typical non-Hispanic white woman earned 75 percent of what the typical non-Hispanic white man earned. For non-Hispanic black women, this was 60 percent of the typical non-Hispanic white man’s earnings, and while the typical Hispanic woman earned only 55 percent.

So if you think about Equal Pay Day being when a woman has to work until – for free, essentially, to equal a man, for black and Hispanic women, they have to work a lot longer. So this is something that I think is masked in the data. If you just compare, for example, non-Hispanic black women to non-Hispanic black men, the gap looks better, but that just shows you that there are big racial differences as well.

When you think about the U.S. versus other countries – and this is something that came up in the last section – the gender pay gap in the United States hasn’t substantially changed since 2000, but other industrialized nations have been improving. And so from the 2000 up to the latest data available, the pay gap fell fastest in the United Kingdom, followed by Japan, Belgium, Ireland, Denmark. As a result, the U.S. pay gap is currently larger than that of many industrialized nations.

So this picture gives you an idea of what’s going on. This is relative to the gap in the United States. And it tells you that all these countries to the left are doing better, and the countries to the right are doing worse, in terms of the gender pay gap. And so that, I think, is really striking.

According to the OECD, the gender wage gap in the United States is about 2.5 percentage points larger than the OECD average, so that’s kind of aggregating. And just to give you a comparison, the gender wage gap in New Zealand is less than a third of what it is in the United States, and in Norway it’s 11 percentage points less than the United States. And even in Italy, it’s 7 percentage points lower. So these are big differences that I think are really important.

So let’s think about what’s underlying the gender wage gap. If we look historically, there were big differences – and people used to cite this all the time – between the education and experience of women. So in the 1980s and 1990s, if you look in the ’70s for example, women had much less experience, they were much less attached to the labor market, and so that was part of the explanation for why they were doing worse. They also tended to be less educated than men, and that was another factor.

In the 1980s, you see these things starting to change, and so we see the gender gap in experience declining as women have become more and more attached to the labor force. And that explains a large fraction of the decline in the gender wage gap that we observe in the 1980s. In the 1990s, we see women’s education kind of helping improve the gap, and now the gap in education actually un-explains the gender pay gap because women are more likely to be enrolled in college than men. So these factors are no longer kind of our primary factors in understanding the gender pay gap.

And this just gives you an idea – I think this graph is really compelling – of the share of postsecondary degrees received by women, and the dotted line – dashed line is at 50 percent. You see that women at the doctoral, master and bachelor’s level all exceed—the fraction women exceeds men.

- So this wage gap grows with experience, and this is something, I think, that was referenced earlier. That if we look at an individual person over time, what we see is that at the beginning, the gap between men and women early in their career is relatively small, and then becomes larger with time. And one of the most compelling studies I’ve seen is work by Claudia Goldin, Marianne Bertrand and Larry Katz, where they looked at Chicago MBA students. And this is really interesting because one of the big things when you say, oh, men earn less than women, and you say, well, they have different skills or whatever, they’re different and so you can’t really compare them, here they’re looking at MBA graduates from Chicago. So it’s a pretty similar group, the men and women who graduate from these programs. They’re all really attached to the labor market, and we can actually observe their grades, the courses they took and things like that.

And what you see is that at the beginning of their careers, there’s very little gap in pay for men and women and it’s increasing over time. And one of the things that they conclude, and I think that was referenced, is that part of what’s going on is that they’re taking off time to have children and they’re facing that hit in the workplace as a result.

So this is a graph from Claudia Goldin’s work which shows the difference between female and male earnings among college graduates by age for one cohort. So think of it as following the same people over time. And the gap starts out relatively low, at negative .1, and then it’s getting bigger. That’s what the decline is, the gap is getting bigger, and we’re moving away from zero over time as they age.

- So at the early stages in their careers, each generation of young women has fared better than the previous generation, so we’re doing better over time. In 1980, the typical 18-to-34-year-old woman who worked earned about 74 cents an hour for every dollar the typical male earned, but by 2014, this figure had increased to 91 cents. And one of the potential explanations for this is that women are delaying their childbearing, so they’re staying in the labor market, they’re getting education, and they’re delaying their childbearing and taking that hit later on. So they’re not kind of hindering their investment early on.

Another factor that was brought up that I think is really worth thinking about is differences in occupation. And this one I think is interesting because it’s not clear how you think about differences in occupation. So just to give you some of the information, the research, Blau and Kahn show that differences in occupation and industry pay an important role in the gender pay gap. I think they say that it explains about 51 percent of the gap we observe.

The BLS – so this may have been different data from what was discussed earlier – only reports one occupation in which women out-earn men, and that was stock clerks and order fillers. And there are occupations that are really the opposite: personal financial advisers, where the pay gap is 39 percent within that occupation; physicians and surgeons, 38 percent; and securities, commodities and financial services sales, which is 35 percent.

But this brings up a bigger issue of whether we should be controlling for education. Should we be saying, well, women and men are working in different occupations, so it’s OK that they’re getting paid differently? And the reason that this is something worth considering is that if the reason that women are choosing the occupations they choose are because they know they’re going to face discrimination, then isn’t that something we want to account for in the gender pay gap? So don’t we want to take into account the fact that their choices are a result of discrimination that they’re facing in the labor market, either a hostile work environment or something like that?

And so when people talk about the idea that once you control for all these things, industry and occupation and other characteristics, the gap gets very small, but it’s not clear that that’s really the right thing to do and the right way to think about it. And I think when you see that in the newspaper, which you see all the time, while there’s not much of a gender pay gap once you take all these things into account, you really want to think about do we want to take all these things as givens, as choices that people made that are not influenced by the labor market and the discriminatory factors that they face?

- Even within occupation, the pay gap still doesn’t fully disappear, so research shows that there’s still about 38 percent of the pay gap that remains even after we take account of all these things. And so then the question becomes, what’s in the residual? Well, the residual, in economics and in statistics, is basically the left over part, the part that we don’t know and we can’t kind of attach to something. So what is in this residual? What’s this 38 percent that’s left over?

One thing is discrimination. So discrimination is out there. There’s a lot of evidence that discrimination exists. We think it’s probably improving over time as this residual gets smaller, but again, because it’s this residual, it’s very hard to measure.

So there are some really interesting resume studies that you may read about in the New York Times sometimes. They talk about sending resumes where you kind of randomize what the name of the person is on the resume – and so they’ve done it for race, they’ve done it for gender – and see how people respond differently to the exact same resume with a different name on it. And so there, you really do have the same-quality person and you are treating them differently, which is, by definition, discrimination. And there’s lots of evidence that this type of discrimination still exists.

The other thing that I just want to highlight that I think is really interesting is that women differentially negotiate relative to men. And this is something that I find particularly troubling, as I have certainly experienced this. And once I learned about this research, it changed my negotiating behavior as a result because I realized that I was making less when I was a professor at UCLA and I looked up my salary and realized that I was, by $20,000, the lowest-paid associate – tenured associate professor in the department. And I had just got a job offer, so I had negotiated and I had just done very badly. And so I did go to my department chair and said, this doesn’t look good, as the only woman; and they were very responsive and raised my pay. So that was good.

But this observation, I think, is really key. Research shows that women are less likely to negotiate, and as a result, they often earn less.

One of the things that’s also interesting is that women are penalized for negotiating. So this goes back to the idea that you’re perceived as bossy or pushy or whatever, so there is this kind of negative perception that is something that we as society need to deal with.

One of the things that I think is really important is the idea of pay transparency. I think if everyone knows what the job pays, it’s much easier for you to say, this is what I should be making. Right? The idea of not knowing and that uncertainty makes women less likely to negotiate.

So there are lots of policies that we can do that were mentioned earlier. I think promoting pay transparency is one thing. Paid leave and family-friendly policies would also likely improve the gender pay gap. Research shows that when women have access to paid maternity leave, a year after giving birth they work more and have higher earnings. And again, as was pointed out, the cost of losing workers is very high to firms. So replacing a worker is very costly, and so there are benefits on that dimension.

Lack of access to leave or affordable child care prevents some women who would like to work from doing so. And one of the interesting statistics is that Blau and Kahn showed that if the U.S. adopted these family-friendly policies that other European countries have, female labor force participation would be four percentage points higher , that women would be more attached to the labor force, and as a result, our GDP would be higher.

So to conclude, just to give you an idea of kind of the macro implications of this, without the increase in employment and hours worked among women since 1970 – so if we think about how much women have contributed – our GDP would be $2 trillion smaller. From a business’s perspective, policies that promote women’s participation can also increase worker productivity and worker retention. And while these policies can help narrow the gender pay gap, they also allow businesses to attract and retain the strongest talent, which boosts labor productivity and benefits the economy as a whole. So individuals benefit, businesses benefit and the economy benefits.

That’s it. (Applause.)

- RAMPELL: So thank you for that great overview about many of the factors that go into – that contribute to the pay gap.

You mentioned one thing that I’m very interested in, pay transparency, and you talked about your own circumstance, where I guess there were public records about what everyone was earning.

- BLACK: Yes.

- RAMPELL: I’m curious, are you aware of any larger-scale, real-world experiments of any kind where there has been more pay transparency and that has, or has not, for that matter, affected the gender pay gap? Like, has anybody looked at whether at public universities there is less of a pay gap than at private ones because, you know, this information is freely available?

- BLACK: So I don’t – I’m not aware of any studies that have done that. There’s actually – while I was at UCLA, they did a study because the Sacramento Bee actually publishes all the pay of everyone at UCLA. This is how I found it out. And what they did was they randomized who found out – they randomly sent emails to some faculty and not others letting them know that their salaries were all available online, because most people didn’t know, and then compared how people did afterwards. But they weren’t looking at the gender pay gap, so I don’t remember if they – I think they may not have looked at it, but I’m not sure.

But that’s the only study I’ve seen of this type at all. I think there just aren’t very many circumstances where all of a sudden you just get information about people’s pay. What they did find was that people were less happy, as a result, because they find out that they’re not doing so well. (Laughter.)

- RAMPELL: I see. What about in terms of the negotiation gap, that women don’t negotiate as aggressively as men, but on the other hand, if they do negotiate more aggressively, that can be held against them: seen as unlikable, nobody wants to work with them, et ceera? Are there policy tools or other tools that we have – and not necessarily ones that come from Washington – that could help narrow that contributor to the pay gap?

- BLACK: I think that’s a really good question because this is something that I puzzled over when I first heard about this research. It’s a Catch-22, right? That you should negotiate because you’re not getting enough money and you’re not getting paid the same salary that you should be getting, but there’s a cost to you. So in my own personal experience – and so this is not very good economic research – but from my own personal experience, a lot of the negotiating happens after they’ve already offered you the job. And so I was really worried, when I was negotiating, that I was going to be perceived badly because I asked for a lot more when I moved to Texas than from UCLA, because I had learned about this.

And then people don’t remember in the long run. Like, someone even said to me, I can’t believe you asked for this, because my department chair actually told the other people what I had asked for. And I was, like, I’m asking for anything – if there’s anything I think that if a guy asked in a year and I hadn’t asked for it, would I be mad, and I asked for everything. And he went and told people that I had asked for this, and they were, like, I can’t believe you asked for it. And now these people are my friends and they’re happy, right, because now they can ask for it the next time they negotiate.

So I do think this is a bit of a Catch-22 and there isn’t really an answer of how to get round the negative perception, but I do think because a lot of negotiation happens after you’ve already gotten the job, that it’s still something we should really work on. And I think from a policy perspective, pay transparency is really, really important because if you don’t know what you can ask for, women are less likely to ask. So if there’s uncertainty whether you can negotiate, women are more likely to say, OK, thank you, and not ask.

- RAMPELL: You mentioned during your presentation that a lot of firms see higher productivity, higher retention rates, things like that. I mean, I know Laszlo Bock at Google has talked about this quite publicly, that it’s been good for business for them to have a generous family leave program; they hold on to workers for longer. So if that’s the case, why aren’t more firms doing it? I mean, if it is good for the bottom line, why aren’t more firms doing it? Are they getting the accounting wrong? Is it just that they’re too small to be able to, you know, provide these kinds of perks; or they’re afraid of, like, adverse selection, that they’re going to get all the workers who are, you know, planning to go on leave after leave after leave, or what? I mean, why, if it is so good for businesses, why aren’t they doing it on their own? What’s the market failure?

- BLACK: And I think that’s a really good question because I wonder this about a whole bunch of things. Like there are a whole bunch of things that we think are good for productivity that firms aren’t doing that I don’t totally understand. I think in this case, there is the issue that potentially you could get this adverse selection, which is, the people who decide they want to try to work for these firms are the ones who are going to take advantage of the benefits, right, and say, OK, all the women are going to go work at this firm because they offer paid leave.

In reality, things like paid leave are a family thing, not a woman’s issue. But also, that doesn’t seem to be what’s happening. But I think that is one reason, and because of that, I think that’s why we do need kind of a government intervention, a kind of collective action to kind of fix that problem.

- RAMPELL: So, related to that, I wanted to pitch to you the same question that I tried asking several times, but I’m not sure I asked clearly enough, in the previous panel, which is, how do you prevent these kinds of family-friendly policies from being seen as women-targeted policies and therefore sort of subtly encourage employers to not hire women because they figure they’ll be more expensive staffers?

- BLACK: Right.

- RAMPELL: I mean, how do you basically make the workplace more family friendly but, given that women are more likely to take advantage of those kind of policies, how do you not discourage employers from hiring women, as a result?

- BLACK: Right. Well, I think, I mean, one thing is that – I think that too is a good question. You’re asking very good questions, and things that I’ve puzzled over. One of the things that they’ve actually implemented in parts of Europe is trying to make it more of a gender-neutral leave; that it’s not just a women’s thing, it’s a family leave. And in fact, some parts – I think in Norway, since I’ve done a lot of research in Norway, you actually – the men have their own leave, and they will lose it if they don’t take it. So you actually as a family will have more leave if both the woman and the man leave.

But even there, they have problems that men are not taking it up as much as women, and so there’s some research showing that if their family takes it up, you’re more likely to take it up; that there are these big peer effects, and so suggesting that it needs to be kind of a societal movement that says this is how we as a society think it should be.

But I think it is – it is an issue. It doesn’t seem like it’s really happened, but it’s borne out in terms of the firms – at least my understanding of the firms who have adopted these policies. So I don’t think the problem has been realized, but I think it’s something that you have to think about.

- RAMPELL: What about child care? Is there any research that suggests that greater access to affordable child care, or even longer school days, has any effect on women’s attachment to the labor force and the pay gap?

- BLACK: Yeah. So I think the research is actually really good in terms of – that access to child care increases women’s labor force participation, access to affordable and quality child care actually also is a great investment in children, so I think that’s really a win-win; that the evidence is that women become more attached to the labor market or stay attached, and the children benefit, as well.

- RAMPELL: What about in terms of the pay gap? Do we know yet whether that has any effect?

- BLACK: I’m trying to think – I think most of the research has focused on – I don’t think it’s actually focused on the wage gap.

- RAMPELL: OK. That’s fine.

This is another question that I had mentioned in the previous session, and it sounds like you have some thoughts on this, which is, to what extent should we be encouraging women to go into occupations or industries that are more lucrative? You know, the prototypical example that I often hear, particularly from conservatives, is, why are you majoring in dance history rather than computer science? You know, that that would do a lot to close the pay gap.

- BLACK: Right.

- RAMPELL: To what extent would – could or should, I guess, the government try to incentivize women to enter – to make different choices that could potentially lead to higher-paying careers?

- BLACK: I think it depends on why they’re making the choices that they’re making, right? If it’s just that they, you know, prefer one thing over the other, I think that doesn’t seem like it’s something that necessarily would require government intervention. However, there’s a lot of evidence that, starting really early on, there are gender norms and there are media bias, implicit bias, there’s all this stuff that children face that affects the choices that they make.

And so if you really thought that women didn’t like doing math, then pushing women to do math isn’t a good thing. If you thought women don’t like doing math because they experienced an environment that they are not comfortable in, they’re not encouraged societally, they’re told they’re not as good at it, then that’s something we need to fix. And so I think it depends on what the root cause is for the different choices. To the extent that it’s really, I prefer one thing over the other but everything else is equal, then it’s, you know, not something we necessarily would worry about. If it’s the result of a circumstance that is pushing me in one direction over the other, then I think that’s something where the government should step in.

- RAMPELL: What about, for example, giving more financial aid to majors that are tied to more lucrative careers, or something like that? I mean, has that been tried? Is that something that’s worth looking into?

- BLACK: There’s been some research that shows – this was a student of mine – where it looked at the SMART Grant program, that provided incentive to major in STEM fields and kind of with a little bit of extra money and said – and finds some effect that people will adjust their major. I don’t know that I think that’s the way to go about the gender pay gap, because I think, A, it’s starting much earlier, and – yeah.

And I think a lot of what we can do here is an information story, as well; that people don’t know about the majors, they don’t know about schools, and I think a lot of the decisions they make when you look at 17-year-olds are really not that well – as someone who has an 18-year-old stepson – are not as well informed as you might hope when they’re making life decisions. So I don’t know that I think that that’s necessarily the direction that I would go first.

- RAMPELL: I think those are – I think we’re good. Yes? OK, I think we’re out of time.

- BLACK: Oh. OK.

- RAMPELL: But thank you so much for joining us and for this presentation.

- BLACK: Thank you.

- RAMPELL: And thank you, everyone, for attending. (Applause.)

- KESSLER: Thank you so much. Thank you, Catherine. Thank you, Sandy. Thanks, everybody, for coming today.

This is – as you’ve said, it’s the interesting kind of divisive political holiday about a gap that we would like to see disappear. I hope people really profited from this. I thought it was a really full discussion.

I really appreciate you bringing a presentation to this, as well. And if it’s available for other folks, we would love to send it out.

- BLACK: Absolutely.

- KESSLER: So thank you so much. (Applause.)

(END)