Report Published September 7, 2012 · Updated September 7, 2012 · 16 minute read

America Makes... Will Asia Take?

Ed Gerwin

A rapidly growing Asia wants the products and services that America excels at producing–from aircraft, food, and financial services to heavy equipment and health care. But will Asia “Buy American?” Not if key American exports continue to face significant trade barriers in the region. In this report, we identify five tremendous and growing opportunities for U.S. exports to Asia. America can fully seize these and other opportunities–and the economic growth and good jobs that they will support—but only by aggressively using global trade rules and new trade deals to win greater fairness for U.S. trade in the region.

Coca-Cola has put an Asian spin on packaged milkshakes. Coke’s Minute Maid brand “Pulpy” shakes, first developed for Chinese palates, now account for $1 billion in sales in 20 countries.1 Other global American companies are racing to create innovative products that align with Asia’s preferences and meet its growing demand.2

America makes what Asia wants. But can Asia buy what America has to sell?

Third Way projects that, in 2020, leading Asia-Pacific* markets will import $10 trillion in goods–and trillions more in services. This explosive growth will present hundreds of billions in new export opportunities for America’s world-leading manufacturers, food producers, and service providers, potentially supporting millions of jobs for our middle class.3

There are various definitions of “Asia” and “Asia-Pacific.” In this report, our focus is on the export opportunities available to the United States in the countries of East Asia and Oceana, as well as India.

But opportunities are not guarantees. America’s foreign competitors have a strong lead in grabbing Asia’s vibrant growth. And they benefit from an array of barriers that block American exports to the region.

This report explores five key sectors in which Asia’s rapidly growing demand has vast potential for U.S. exports, while noting some of the serious barriers that strongly favor America’s competition. We conclude that the United States can grow its share of trade to the Asia-Pacific—but only if it uses tough trade enforcement and new trade deals to clear away the region’s many remaining impediments to U.S. trade.

What Asia Wants

Key Megatrends Powering Growing Asia-Pacific Imports

In the last 50 years, Asia has grown dramatically by becoming an export giant. In the decades ahead, Asia will also increasingly be a major, global force in importing. Swelling cities, expanding wealth, and evolving preferences are fundamentally altering the buying decisions of Asia’s consumers and businesses, creating trillions of dollars in new demand and lucrative markets for a wide array of goods and services.

Urban growth is a key driver of Asia’s expanding consumption and surging imports. Cities are potent growth creators, accounting for 80% of global GDP.4 Asia is currently home to half of the world’s urban population and will lead the world in the rate of urban growth in the coming decades. By 2020, urban Asia will need to find room for an additional 290 million people. China will have 131 cities with populations of at least one million, and Southeast Asia will have 20 “secondary cities” of over a million.5

The Asia-Pacific is also increasingly affluent. Over the last decade, personal incomes have more than doubled in the ten member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).6 India now has more middle class people (400 million) than America has people.7 And each day, China creates 159 new millionaires.8 By 2020, the Asia-Pacific middle class will expand by more than 1.2 billion, and will make up half of the world’s middle class consumers.9 This rapidly increasing prosperity will at least double Asia’s level of consumption—to almost $9 trillion—by 2020.10

Finally, as the Asia-Pacific becomes more urban and affluent, it is also undergoing a rapid evolution in preferences and tastes. New middle-class consumers can increasingly afford travel, entertainment, and luxury items.11 Others are “trading up,” replacing motorbikes with cars and local goods with foreign brands. Busy urban families want greater convenience and are adopting Western-influenced diets and relying on modern financial services.

Asia’s consumers have rapidly embraced cutting-edge communications technologies and use mobile devices to conduct business and shop online at over twice the rate of U.S. consumers. And, as Asia’s people become better off, they are seeking improved health care, new housing, and better education for their children, and are pressing for cleaner air and water, improved sanitation, and modern transit.12

In the coming decade, these megatrends will propel surging imports into the Asia-Pacific. But will America benefit from this tremendous opportunity?

Five Key Sectors for U.S. Exports to Asia

Opportunities Abound... but Many Barriers Remain

Some claim that “America doesn’t make anything anymore.” But, in fact, America is a production powerhouse.

The United States is the world’s largest manufacturer and a global leader in producing an array of high-value consumer and industrial products.13 America is a global force in farming and processed food and the world’s #1 exporter of services.14 U.S. producers and workers have what it takes to supply a wide range of Asia’s growing needs. And they are willing and able to battle for opportunities in growing Asia-Pacific markets, even in the face of serious challenges posed by foreign competitors and foreign governments.

We highlight below five key sectors in which America’s strengths are especially well matched to Asia’s growing needs—while also noting barriers that can keep America from recapturing a greater share of Asia-Pacific trade.

1. Infrastructure Investment

A growing, urban, and more affluent Asia-Pacific region will require massive investment in infrastructure in the coming decades.

The United Nations estimates that Asia will need to spend over $600 billion annually on infrastructure to support new development.15 Cities including Bangkok, Jakarta, and Manila will require billions in investment to build roads and transit; update inadequate power, water, and sanitation systems; and address severe housing shortages.16 And, over the next five years, India alone will spend a trillion dollars on some 600 major infrastructure projects, including many public-private initiatives with foreign firms.17

This significant investment could create vast new export opportunities in Asia for “Made in America” products and services.

As the world’s third-largest exporter of capital equipment, the United States can supply construction equipment, power systems, and other vital machinery for the region’s infrastructure projects.18 U.S. firms are also global leaders in the water treatment systems, renewable energy products, and green building technologies that countries like China, India, and Vietnam will increasingly need to address environmental challenges.19 And with falling U.S. energy costs and rising foreign wages, many U.S. manufacturers are increasing their competitive edge over Asian rivals.20

American companies are also leaders in infrastructure services. Five of the world’s top 10 global design services firms are based in the United States. Large and small U.S. companies can provide world-class architecture, construction, and project management services for the many new cities, airports, hospitals, and schools that the Asia-Pacific region will require.21

But America won’t fully benefit from Asia’s rapid infrastructure growth as long as U.S. exports face an array of trade barriers that favor other foreign suppliers. China and Indonesia, for instance, impose burdensome qualification rules and restrictions on U.S. construction and engineering firms, while restrictive practices have limited U.S. contractors to less than 1% of Japan’s $189 billion public works sector.22 And U.S. and other foreign investors have long been excluded from opportunities to invest in much of Asia’s multi-trillion-dollar infrastructure sector.23

India’s DMIC: The Mother of Infrastructure Projects

India’s $90 billion Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) project is colossal in scale. It will include three seaports, six airports, and nine vast industrial zones, all served by extensive, world-class infrastructure.24 The U.S. Commerce Department sees tremendous prospects for U.S. architecture firms in supporting the DMIC, and lucrative opportunities to collaborate in building new housing and commercial buildings in cities such as Bangalore, Chennai, and Kolkata.25

2. Food Demand and Diversity

Consumers in emerging Asia want greater convenience, quality, and safety in their food choices and are moving from Asian staples to Western-influenced diets. Asia’s supermarket sector is also seeing explosive growth.26 These developments are creating growing market opportunities for high-value U.S. foods, including meat, dairy, fruits, vegetables, and prepared foods, as well as key commodities.27

These trends are evident in current U.S. trade data:

- Higher incomes throughout Southeast Asia have markedly changed eating habits, resulting in surging imports of U.S. meats, animal feed, fresh fruits, potato chips, baked goods, and other foods.28

- In 2011, eight of the top 15 destinations for U.S. farm exports were in Asia.29

These patterns will continue and accelerate in the coming decades:

- By 2015, India’s market for convenience and ready-to-eat foods will surge by 40% to 60%.30

- By 2020, Asia’s demand for food will more than double, to nearly $3 trillion.31

- By 2030, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam will see major declines in their farm self-sufficiency, requiring more farm imports.32

As global leaders in producing and exporting an extensive menu of food products—from commodities and meats to fruits, vegetables and processed foods—America’s farmers, ranchers, and food manufacturers are in a strong position to help feed Asia’s growing appetite.

One-in-three acres on American farms feeds hungry overseas consumers.33 In 2011, America’s farm sector enjoyed a record $137 billion in exports and a $43 billion trade surplus.34 U.S. farms supply over 50% of world exports of corn and over 40% of global exports of soybeans and cotton.35 Over a third (19 of 50) of the world’s leading food and beverage processing firms are based in the United States, and U.S. processed food exports were almost $50 billion in 2008.36

But it will be difficult to expand America’s share of regional farm trade as long as significant barriers prevent many American foods from reaching Asian tables. Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam hit U.S. processed foods with duties of over 50%, while India’s duties on chicken range up to 100%.37 Standards that have no scientific basis can shut out U.S. exports of dairy products (e.g., India), fruits and vegetables (e.g., China), meats (e.g., Malaysia), and organic foods (e.g., Japan).38

The Big Cheese

Where America has a fair shot at foreign markets, we do well. Take pizza: Asian consumers have traditionally not been big on cheese. But, with the booming growth of U.S. food chains like Pizza Hut and McDonalds, the region’s diners increasingly treat themselves to pizza and cheeseburgers. And that requires record amounts of imported cheese. In the first quarter of 2011, U.S. cheese exports to Asia doubled over the same period in 2010. Driven by significant Asian demand, U.S. dairy exports are growing eight times faster than U.S. domestic shipments.39

3. Better Health Care and Education

As they become more prosperous, Asia-Pacific families are demanding better medical care and quality education for their children—and they are willing to pay for both. In Thailand, the middle class spends twice as much on health care and education as lower-income consumers, while China’s consumers spend the highest portion of their incomes on education and medical care. By 2020, Asia’s per-person spending on health care is projected to more than double, almost reaching U.S. levels.40

In many Asia-Pacific countries, health care systems are ill-equipped to meet growing demand. India will need to add 80,000 new hospital beds in each of the next five years just to keep up with local needs.41 And public health experts predict that Asian health systems will be overwhelmed by surging rates of chronic conditions—like cancer and heart disease—that accompany longer lifespans and increased affluence.42

As the world’s #1 market for private health care, the United States is home to the world’s largest and most advanced providers of health care services and to global leaders in drugs and medical devices.43 Asia’s expanding health care needs will afford significant export openings for U.S. firms that build and manage hospitals and develop cutting-edge drugs and devices. For example, the U.S. medical device industry—already the world’s most competitive—should have many opportunities to build on its leading position in markets like India, which is growing 15% annually.44

But even America’s highly competitive health care exports are often no match for trade barriers that continue to exist throughout the Asia-Pacific. Financing and reimbursement policies in many Asia-Pacific markets can limit U.S. drug and medical device exports. And in countries like Indonesia, U.S. pharmaceutical firms face local manufacturing requirements and technology transfer rules that threaten their critical intellectual property rights.45

From Hanoi to Harvard

When a foreign student studies at a U.S. college, that’s a U.S. export of education services. In 2009, America ran an education trade surplus of over $14 billion. During the 2010-2011 school year, 468,000 Asia-Pacific students studied at U.S. universities, accounting for 65% of all foreign students. Asia’s surging demand for instruction (especially in English) is forecast to continue to grow.46 And, with a university system that includes 17 of the world’s top 20 universities, America is well-positioned to capitalize on Asia’s thirst for learning.47

4. Banking, Insurance, and Finance

More than a billion people in Southeast Asia and China currently lack access to financial services.48 Of India’s 1 billion people, only 20 million are covered by health insurance plans.49 And savers in China—with a national savings rate four times higher than America’s—have few attractive investment options to save for retirement.50

As Asia becomes more urban and middle class, addressing these financial service deficits could create vast prospects for America’s world-leading banking, insurance, and finance firms.51 (A third of the world’s 15 largest insurance companies and dozen largest banks are American.52) Asia’s movement toward private pensions could create billions in new business for U.S. finance and insurance providers.53 Asian drivers will need insurance for millions of new cars. And rapid urbanization will require a flood of new housing loans, which are projected to grow 2.2 times—to $3.7 trillion—by 2020.54

But an array of trade and investment restrictions also keeps U.S. firms from grabbing a bigger share of Asia’s surging financial services market. Equity limits, administrative hassles, and restrictions on branch operations limit business for U.S. banks and insurers in India, Indonesia, and Japan. U.S. firms can’t get licenses to provide pensions in China, a market that will add over 125 million seniors by 2020.55 And, China denies full access to its $1 trillion market for electronic payment services, in violation of WTO rules.56

5. A Growing Volume of Vehicles

As the Asia-Pacific grows more affluent, its people are increasingly taking to the roads, rails, and skies. In the coming decade, travel by Asia-Pacific residents will be the fastest growing segment of international travel.57 By 2020:

- Asia-Pacific residents will account for one-third of the world’s outbound travel spending (up from 21% in 2008).

- The number of international travelers from the region will almost double (to 447 million).58

And the region’s roads will be increasingly crowded. By 2020, China’s drivers will buy a projected 30 million cars annually. That’s up from 18 million in 2010 and twice the size of the current U.S. auto market. Demand for cars in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand will grow by over 10% annually.59 Analysts forecast that America’s strong transport and vehicle sectors should be exceptionally well-positioned to reap the benefits of growing Asia-Pacific demand.60

As America’s largest exporter of manufactured goods, Boeing sells over 80% of its aircraft to air carriers in over 100 countries.61 The company recently won its largest commercial aircraft order ever, agreeing to sell 230 aircraft for over $22 billion to Lion Air, a fast-growing airline serving Indonesia’s booming market.62

American-made cars account for a growing share of U.S. exports to major Asia-Pacific markets. America’s 10th fastest growing export sector is the export of cars to China, with passenger vehicle exports to China surging from under 29,000 to over 136,000 between 2009 and 2011. Over half of the 50,000 Cadillacs exported from America each year go to China. U.S. auto plants—including the plants of foreign-based carmakers—are also ramping up exports to South Korea, spurred by the recent U.S. trade deal with Korea. Ford is now shipping Fusion Hybrids to Korea and hopes to eventually export up to 10,000 cars annually to that market. Toyota exports Indiana-made Sienna minivans to Korea, while Volkswagen is planning to ship Tennessee-built Passats there as well.63

But further growth in U.S. vehicle exports to Asia will also require clearing away foreign barriers and entrenched practices that obstruct American exports to the region. High duties and other restrictions in the region protect local auto producers. India imposes a 60% duty on U.S. cars, while U.S. auto exports also face high duties and/or discriminatory taxes in countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.64 And experts fear that China may use coercive “indigenous innovation” rules to coopt U.S. technologies for its competing China-made C-919 passenger aircraft and for “New Energy Vehicles,” like hybrid and electric cars.65

Emerging Asia Takes to the Skies

Last year, Boeing chose Asia to launch the “world tour” for the new 787 “Dreamliner.”66 It’s no wonder. Half of global growth in air traffic over the next 20 years will be driven by Asia-Pacific travel. By 2030, the Asia-Pacific will need 11,450 new aircraft, valued at over $1.5 trillion.67

The Government’s Vital role

Achieving the Promise of Asia-Pacific Trade

America’s globally competitive manufacturers, farmers, and service firms have many exciting prospects in an Asia-Pacific market that will import over $10 trillion in goods and services in 2020. And they’re willing to do the heavy lifting that’s required to win new business in the region. But only the U.S. Government has the strength to clear away the many trade barriers that foreign governments use to keep U.S. exporters from reaching their full potential and growing America’s share of regional trade.

For America to expand its slice of Asia-Pacific trade, it must:

- Ensure that our trade officials have the resources they need to promote U.S. exports and enforce America’s rights under international trade rules, through effective programs like the Administration’s National Export Initiative and Interagency Trade Enforcement Center.68

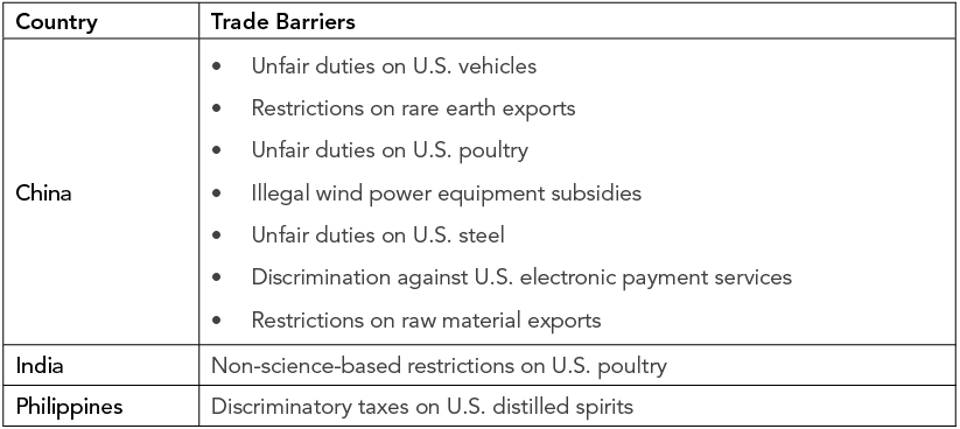

- Continue aggressive trade enforcement against Asia-Pacific trade barriers that violate existing international trade rules. (See Appendix I.)

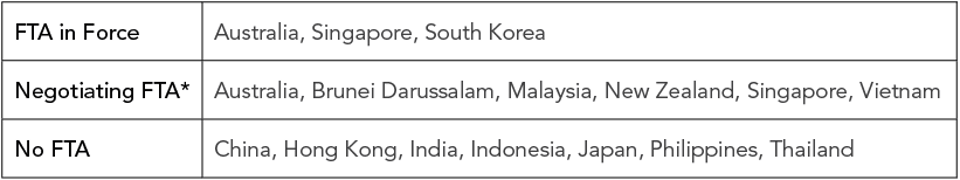

- Forge ahead in negotiating tough, comprehensive trade deals to open key Asia-Pacific markets, beginning with the TransPacific Partnership. (See Appendix II.)

As highlighted previously, Ford, Toyota, and Volkswagen are each ramping up exports of American-built cars to South Korea. This is no coincidence. Rather, it is the direct result of the new Korea-U.S. trade agreement—and persistent bipartisan efforts to use stronger trade rules to gain improved market access for Made-in-America vehicles.

The United States can generate even more exports and support good jobs by aggressively employing trade rules to pry open key Asia-Pacific markets, especially for the many products and services where we have a clear comparative advantage. If we can do this, Asia-Pacific customers will be lining up in ever-growing numbers to “Buy American.”

Appendix I

Recent U.S. WTO Cases against Asia-Pacific Trade Barriers69

Appendix II

U.S. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Major Asia-Pacific Economies70

TransPacific Partnership. TPP negotiating partners also include Chile and Peru, with Canada and Mexico joining soon.