Memo Published February 11, 2026 · 9 minute read

Cleaning Up America’s Natural Gas: Why Lower Emissions are Key to Long-Term LNG Competitiveness

John Hebert

The world faces increasing demand for energy. Even with the rapid growth of lower-carbon technologies, fossil fuels—especially natural gas—remain deeply embedded in the global energy system because of their availability, affordability, and reliability.

In fact, global natural gas consumption is projected to grow by as much as 25 percent by 2050.1 The International Energy Agency estimates that about 300 billion cubic meters of liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capacity will be added globally every year between now and 2030 to meet that demand.2

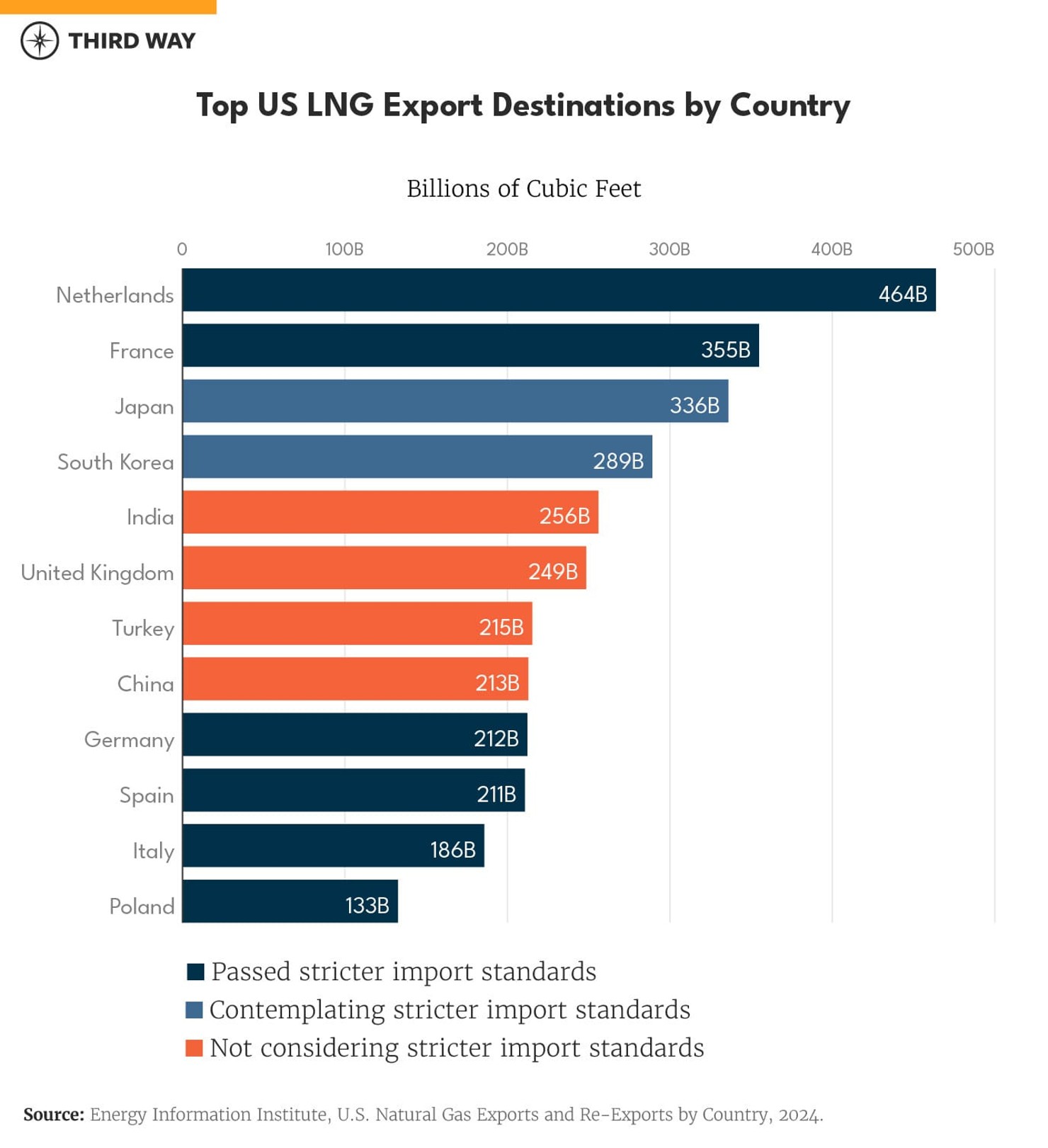

While these trends are economically positive for the United States, the world’s leading natural gas producer and LNG exporter, new global market dynamics may jeopardize America’s place as a default partner for key allies and LNG importers like the European Union, South Korea, and Japan. As LNG export capacity increases around the world, these markets can demand more from their gas suppliers, especially when it comes to environmental performance. In that arena, the U.S. is already well behind many of our competitors.

The Trump Administration’s response to these policies has been to pressure our allies to relax emissions standards in the name of maintaining access to low-cost American gas. But regardless of whether those efforts are successful in the short-term, these markets are clearly trending toward being more conscious of where their gas comes from and how it’s produced.

That means that regardless of how policymakers feel about climate, the way for US gas producers to remain competitive in the future is by positioning American gas as a cleaner, more responsible option than gas from other countries.

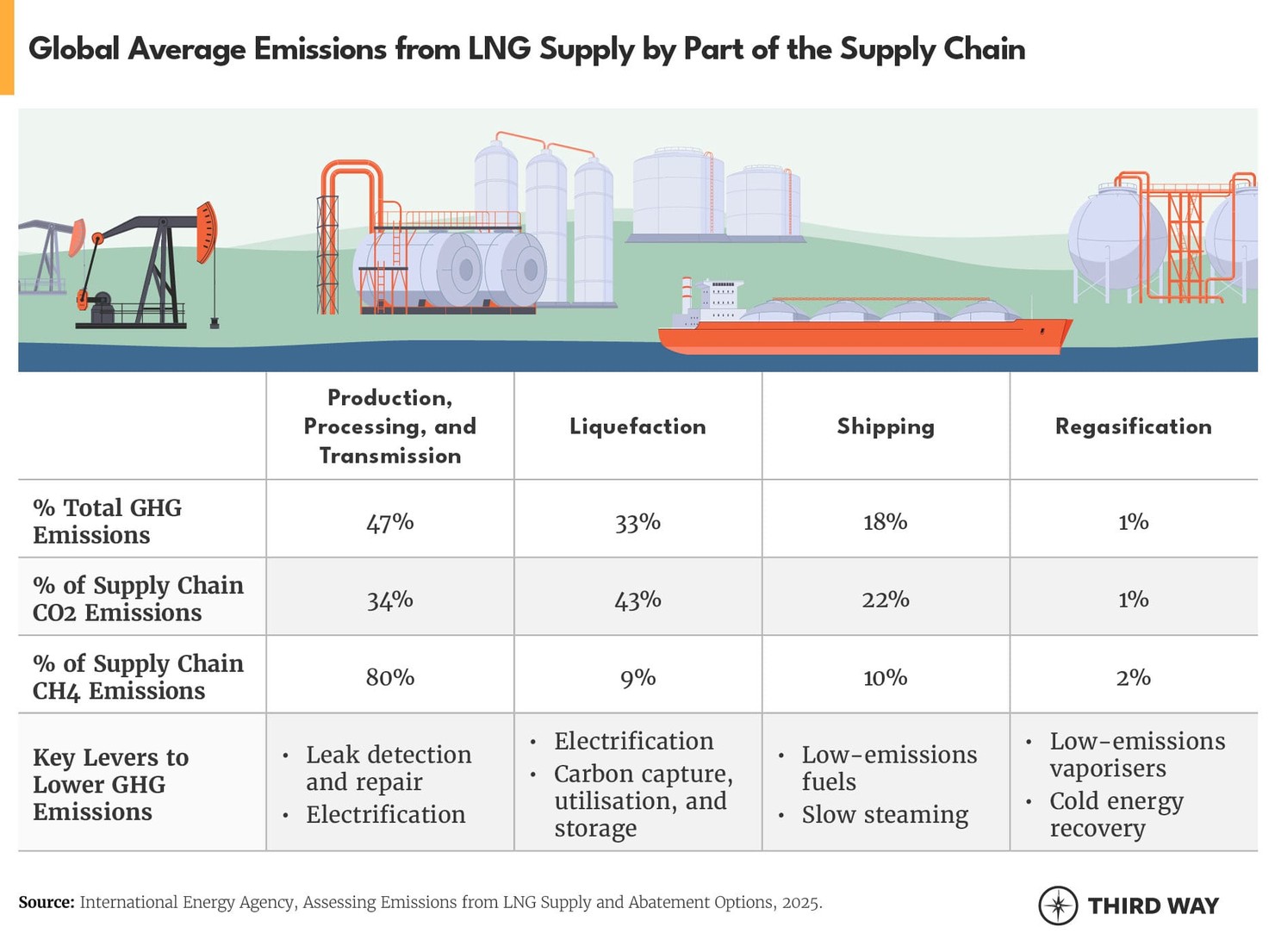

Why Our Allies are Demanding Cleaner Gas

Natural gas is often promoted as a cleaner-burning alternative to coal—and for good reason. When combusted, it emits about 60% less carbon dioxide per unit of energy than coal, which has helped the U.S. and UK power sectors both reduce their emissions by 40-50% over the last two decades alone.3 But burning natural gas still accounts for a significant share of global energy emissions – about 28% of Europe’s and a little over 20% of Japan and Korea’s.4 And although natural gas is a comparatively cleaner fossil fuel than coal, leaks throughout the supply chain can effectively negate a significant portion of the environmental benefits that natural gas offers. That’s because natural gas is primarily composed of methane, a far more potent greenhouse gas that captures more heat in the atmosphere than CO2 does. If natural gas is leaked rather than burned, its global warming potential is about 86 times higher over a 20-year period.

Luckily, reducing upstream emissions from this sector is also one of the most cost-effective climate solutions the world has available, because many mitigation technologies like leak detection systems and equipment upgrades are mature, affordable, and offer operators returns on their investment. In fact, a recent McKinsey analysis found that a $200 billion investment in methane mitigation solutions from the O&G sector could translate into a reduction of about four percent of the world’s GHG emissions.5

The Challenge Facing the US Gas Industry

Many key natural gas importers that care about reducing global emissions have recognized that a more fluid LNG market – characterized by excess global LNG export capacity and cheaper gas supplies – mean that they can shape how gas is produced and traded even outside their borders. The new EU regulation on the reduction of methane emissions includes new obligations for companies to report on and limit the releases of methane through various stages of oil and gas operations – including any emissions occurring outside of the EU and being imported into the EU market. American exporters are now racing to comply before import standards become even stricter in 2027.6

Other major LNG importers like Japan and South Korea are also exploring adopting similarly stringent standards, having co-launched an initiative to improve the transparency of emissions data. And as of this year, 111 countries have signed onto the Global Methane Pledge, a voluntary framework for participating nations to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30 percent below 2020 levels by 2030. While some of these standards are voluntary at the moment, they send a clear market signal from some of the largest global buyers of American LNG—including a majority of the countries importing US LNG last year – that the world is demanding cleaner gas.7

To its credit, much of the oil and gas (O&G) industry has responded to these signals independently. Many operators – especially larger players – have adopted leak detection technologies, reduced flaring and venting, and set rigorous voluntary emissions targets. Some new LNG terminals have even begun integrating carbon capture and storage (CCS) into their projects, though their track record in following through on those plans is mixed. Their motivation is not solely about meeting environmental regulations, since methane leaks also represent lost product and revenue. One analysis by Stanford University estimated that oil and gas operations across the United States emit more than 6 million tons of methane per year, equating to about $1 billion in lost revenue for energy producers every year.

The Problem: The US Trails its Peers in Emissions Abatement

Despite being the world’s largest O&G producer, the U.S. gas industry lags behind many of its peers in containing leaks. Gas from the United States emits more methane on average than gas from the Middle East or Europe and is roughly tied with Russia. There are a variety of reasons for this including aging infrastructure and lack of state or national policy incentives to clean up gas infrastructure, among other factors. These emissions can also vary widely between different operators and basins, with some US production being much more globally competitive than others in terms of emissions intensity. Regardless, the US as a whole has a significant problem when it comes to broadly positioning its LNG for reliable, long-term export agreements with markets that are demanding cleaner gas.

For a highly decentralized market with hundreds of unique players across the supply chain, this provides a huge impetus for federal and state policy action to establish uniform standards and incentives to keep US natural gas competitive globally. And as jurisdictions like the EU contemplate long-term offtake agreements for LNG supplies, we should be ensuring that US LNG is better positioned to meet that demand than supplies from less strategically dependable countries like Qatar or Russia.

How Federal Policy Can Help (or Hurt)

Unlocking investments in methane abatement will require significant efforts beyond just voluntary industry engagement. Market incentives alone haven’t been sufficient to mitigate these emissions thus far, and with natural gas as cheap as it is, it’s often far more affordable for operators to simply accept excess emissions in the form of lost product than make the investments necessary to plug leaks, even if the cost of plugging those leaks is relatively small. This is particularly true in the United States, where operators have already adopted many of the abatement technologies that can be done at no net cost.8 According to the International Energy Agency, about 90 percent of the emissions abatement measures that companies can take will still require some investments that doesn’t generate a complete return on investment, but federal policies can help them close that gap.

These tools have historically included grants for investments in voluntary emissions reduction technologies, robust reporting requirements on methane emissions, and market-based incentives to reduce waste. The Trump Administration is now moving to unwind many of these policies, a move that could weaken U.S. competitiveness at a time when global buyers are increasingly scrutinizing the emissions performance of American LNG exports.

Notable Rollbacks and Delays by the Trump Administration

- EPA Methane Emissions Reduction Program: The IRA appropriated $1.55 billion for the EPA to provide financial and technical assistance for methane monitoring and mitigation.

Status: The One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025 (OBBBA) rescinded all unobligated funds from this program and many of the awards that were made have also been targeted for termination by the Trump Administration. - EPA Waste Emissions Charge and Improved Data Reporting on Methane Emissions: As part of the EPA’s Methane Emissions Reduction Program , the IRA also directed the EPA to impose and collect a charge on methane emissions from facilities that exceed a certain threshold, called the Waste Emissions Charge (WEC). EPA was further required to revise existing reporting requirements on methane emissions to improve data collection under revisions to the GHG Reporting Program (GHGRP), which has collected data on GHG emissions from large GHG emissions sources, including fuel and gas suppliers, since 2008.

Status: In January 2025, President Trump signed a joint resolution of disapproval to void the EPA’s final rule on waste emissions, though the joint resolution only blocked the rule, not the tax itself. The OBBBA further delayed implementation of the WEC from 2024 to 2034. On September 12, 2025, the EPA issued a proposed rule eliminating reporting requirements on GHG emissions altogether, severely limiting the federal government’s ability to accurately track emissions from the O&G sector and other industries, sparking objections from industry trade groups.9 - FERC Proposed Policy Statement on GHG Emission Considerations for Natural Gas Projects: In 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)—which must approve all interstate natural gas projects, including pipelines and LNG terminals—issued a new policy statement that compelled natural gas infrastructure projects to assess the upstream and downstream emissions and the associated climate change impacts of the project.

Status: FERC revoked the draft policy statement in January 2025 at the direction of then chair Mark Christie.

The Road Ahead

As the Trump Administration continues to abandon GHG mitigation policies left and right in the pursuit of an incoherent “Energy Dominance” agenda, those who want to see a stronger and cleaner American gas industry should own a more pragmatic middle ground, pushing for rigorous standards to cut its emissions footprint as a means of making this industry more competitive. Moving forward, policymakers on both sides of the aisle should look to preserve or expand policies that mitigate emissions and strengthen data reporting to position American LNG for long-term success well into the future. These policies include:

- Providing voluntary incentives for methane emissions reduction, as industry has widely supported.

- Maintaining programs that collect and aggregate emissions data, which many countries will eventually require in order to import American LNG into their markets.

- Working productively with key markets like the EU, Japan, and South Korea to set standards that give American gas exporters an advantage, rather than using economic coercion or sabotaging international efforts to set these standards, which makes the US a less reliable long-term partner.

- Supporting federal research and development efforts to cost-effectively identify, monitor, and eliminate methane emissions throughout the natural gas supply chain.

The choice is simple: America can lead on developing a cleaner gas industry to secure global markets, or we can fall behind our competition in the name of resisting environmental progress.