Interview Published April 9, 2018 · 5 minute read

Sandra Black: A Conversation on Equal Pay Day

Rachel Minogue

To highlight Equal Pay Day, Third Way discussed the current state of women in the workforce with economist Sandra Black. Black is a professor of economics at the University of Texas at Austin, where she holds the Audre and Bernard Rapport Centennial Chair in Economics and Public Policy. She recently served on President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers from 2015 to 2017.

Q: Your recent work looks at women’s labor force participation in the U.S. and in other countries. What are the key differences you observe?

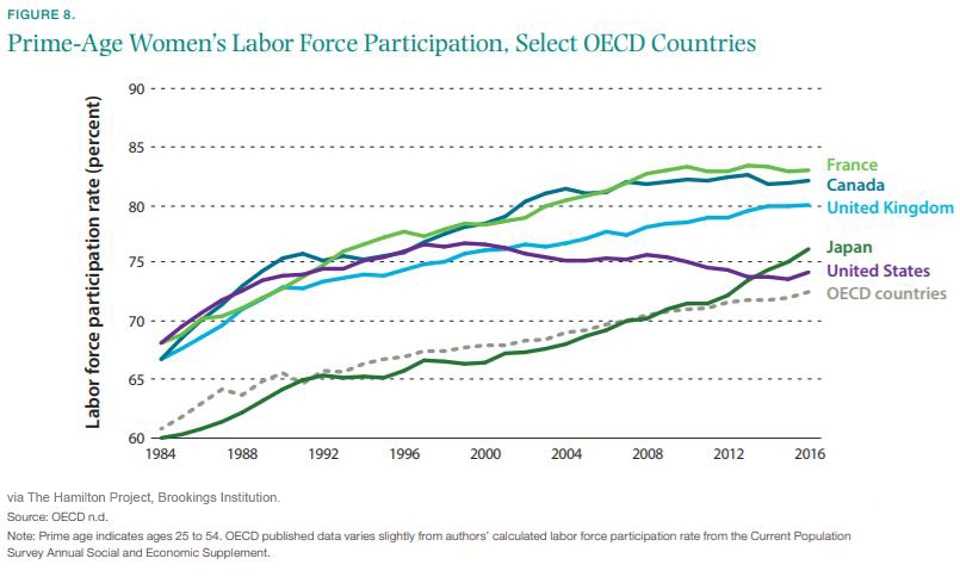

A: In the U.S., prime-age women’s labor force participation (women aged 25 through 54) increased substantially throughout the 80s and 90s. However, this changed in 2000, and labor force participation among these women began to decline.

Now, prime-age women’s labor force participation is trending down, similar to that of prime-age men. This is in sharp contrast to other OECD countries, where prime-age women’s labor force participation has continued to rise. While this trend is not necessarily a bad thing if people are choosing to stay out of the labor force to raise their children, for example, the evidence seems to suggest that this is not the case. The people out of the labor force, among both men and women, tend to be lower-skilled workers with declining labor market opportunities.

Q: What are the best ways policymakers could address this trend?

A: There are a number of factors that could be influencing these trends, suggesting roles for policy on multiple dimensions.

First, the U.S. is the only developed country in the world not to offer paid family leave. Research has shown that these types of policies can improve labor force participation of women. Other family-friendly policies, such as improved access to quality childcare, would also help improve labor force participation rates of women.

Second, both women and men at the lower end of the wage distribution have experienced stagnating wage growth over recent decades. Policies that help improve labor market opportunities of lower-wage workers, such as expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, increasing the minimum wage, and providing paid sick leave to all workers, would make working more attractive and also increase labor force participation rates.

Q: You’ve written that cultural expectations help drive the gender pay gap. What can policymakers do to help overcome pervasive norms on male and female employment?

A: I think part of the problem is that many traditionally female occupations pay very little, which makes these jobs particularly unattractive. Teachers and caregivers provide important roles in our society and are not compensated in a way that represents that importance. Guaranteeing a living wage for all workers would be a good start.

Q: You served on President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), working on the pay gap problem, among other issues. What’s something you took away from that experience?

A: It was frustrating to me how little Congress was willing to do to help working Americans. We were forced to turn to the private sector and try to encourage businesses to “do the right thing.” As a society, we need to demand more.

Q: How did your time on the CEA influence your research and how you approach policy solutions generally?

A: Being in the policy world gave me a much broader perspective. Academics tend to have a very narrow focus, but when I served on the CEA I had to think about a broad range of topics. I am now really interested in understanding why wages are stagnating for lower-wage workers. Since leaving the CEA, it has been exciting to see the new research examining wage stagnation and the potential role of firm market power in hiring on wages, what economists call monopsony. I think this is a very promising area of research and look forward to seeing more.

Q: How would you describe the state of women in economics? Are there ways the field could improve to reach greater gender parity?

A: It is a bit discouraging. I am glad that more people seem to be paying attention to the problem now, but it clearly remains a problem. I think mentorship is a key issue – it is less desirable to enter a field where there are very few people “like you”. This is true for women as well as other underrepresented minorities. Departments need to be cognizant of the situation and work to ensure that the environment is welcoming for all workers.

Q: What’s something in the pay gap debate you feel is often misunderstood, or that more people should better understand?

A: One thing that continues to frustrate me is when people claim that, once you compare women and men with the same education in the same occupation, the wage difference doesn’t look so bad, and things are just fine. When thinking about the gender wage gap, it is important to think carefully about who you want to be comparing. For example, if women are less likely to become managers because of discrimination in the workplace, then saying that women and men in the same occupation make the same wage does not imply there is no discrimination. Instead, in this case, qualified women are not getting promoted when they should be, which is discriminatory.