Report Published July 9, 2019 · 11 minute read

The Opportunity Fund

Ryan Bhandari

Takeaways

- The digital economy has concentrated opportunity in America. A whopping 2,149 of 3,138 US counties shed businesses along with just under 1.6 million jobs from 2006 to 2016. This includes urban, suburban and rural counties as well as predominantly white and predominantly non-white counties.

- Venture capital (VC) plays a critical role in spreading opportunity and the growth of new businesses. Five out of the six most valuable companies in the world were backed by VC during their rise. However, communities all over the country are starved of this crucial catalyst of opportunity.

- In 2015, four metropolitan areas received 80% of venture capital dollars invested across America. This is compared to 50% in 1995. Venture capital is rapidly concentrating investment in a few fortuitous regions.

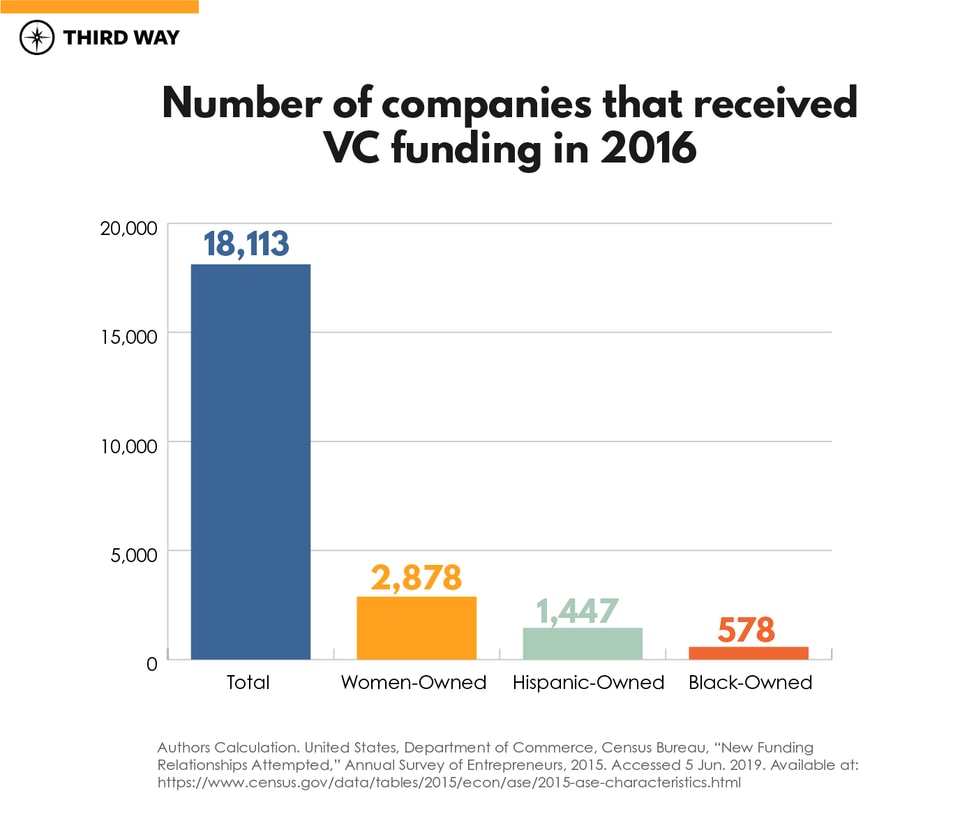

- Women and communities of color are overlooked by traditional venture capital funds. In 2016, just 15% of all businesses receiving venture capital were women-owned, 8% were Hispanic-owned, and 3% were Black-owned.

- To spread opportunity to more people and places, Third Way proposes the creation of an Opportunity Fund that will provide $60 billion in equity capital funding to entrepreneurs, start-ups, and businesses in currently-overlooked areas.

- States can set up their own venture funds or partner with local funds to provide seed capital to businesses within its boundaries that show promising results.

America faces an opportunity crisis. Unless you live in a certain place, have a certain background, or have a certain credential, opportunity in the digital age feels like it is slipping away. Third Way has proposed a series of big ideas so that everyone, everywhere has more opportunity to earn a good life in our modern economy. The idea below addresses the concentration of capital that is essential to growing a business.

The Problem

The economic recovery will be ten years strong this June, but millions across the country still aren’t seeing the effects. Seventy-two percent of the nation’s net job growth since the Great Recession has occurred in metropolitan areas with more than one million people. Meanwhile, in two-thirds of America’s counties, there were fewer businesses in operation in 2016 than 2006, and in more than one-half of the counties there were fewer private sector jobs in 2016 than 2006.1 Even post-recession, much of the country has been hemorrhaging jobs, people, opportunity, and outside investment.

Exhibit A: venture capital (VC). In 1995, 50% of all venture capital dollars went to Silicon Valley, Los Angeles, Boston, and New York City. By 2015, this was true for 80% of VC dollars.2 Over those twenty years, these four metropolitan areas also saw some of the most impressive growth in jobs and businesses. The presence of VC dollars in these places fed the creative spirits of thousands of entrepreneurs vying to create the next big thing.

In fact, one study finds that a 10% increase in the amount of VC in a metro area leads to a 2.6% increase in the number of companies with 5-19 employees, a 2.9% increase in employment at these companies, and a 3.9% increase in total payroll.3 Five out of the six most valuable companies in the world right now received VC money at some point during their ascension.4

In 2018, over $130 billion in VC was invested in the US, surpassing even the amount invested in the late 90’s during the dot com boom.5 The problem is that VC money has become so highly concentrated in a small number of booming metros (in particular Silicon Valley) that budding entrepreneurs are being told to move to one of these areas if they want VC money. A St. Louis-based CEO received a number of such recommendations from VC firms who curtly told him, “Your geography is not a fit for us.”6 The CEO was told that he should emphasize to VC funds that he was in the process of moving to the Bay Area even if it wasn’t true.

There is no reason that a metro area like St. Louis can’t be a destination for VC funding. Talent can be found in every town and city across this country, and VC firms need to do a better job of reaching it.

The clustering of VC funding, and subsequently tech startups, in the Bay Area has put a tremendous amount of strain on the region’s infrastructure. The metro areas of San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose have the most expensive housing in the country, with San Francisco taking home first prize and clocking in with a median rental price of $55,000 per year for a three bedroom unit. San Francisco mayor London Breed recently noted that for every eight new jobs San Francisco creates, only one unit of housing is made. And when such constraints are placed on housing, startups have to pay higher and higher salaries just so their employees can maintain a good standard of living. The businesses themselves will also pay higher and higher rents just to have office space. The other three regions that receive the lion’s share of VC money (Boston, Los Angeles, and New York City) are experiencing the same constraints on housing and rent.

Not only does VC funding tend to overlook people based on where they live, but often it also bypasses women and people of color. In 2016, just 15% of all businesses receiving VC funding were women-owned, 8% were Hispanic-owned, and 3% were black-owned.7 The rest were overwhelmingly white and Asian male entrepreneurs who received funding for their startups.

One reason for this could be the lack of diversity within the industry. Research has shown that it matters who is at the table when an entrepreneur walks through the door and asks for money because investors are predisposed to exhibit a preference for similar people. Yet, just 3% of the workforce at VC firms is black and only 4% is Hispanic, and women make up just 11% of investment partners.8

Venture capital’s lack of geographic and entrepreneurial diversity is starting to get attention. Recognizing the importance of spreading equity investments, entrepreneurs like Steve Case have made a concerted effort to increase the amount of VC dollars reaching heartland America through initiatives like “Rise of the Rest.” Congressman Ro Khanna, who represents Silicon Valley, and Congressman Tim Ryan, who represents an Ohio district, have called on venture capital funds to expand their scope of interest and push money towards possibly unconventional locations.9 Venture capital funds should look to expand equity capital to more communities around the country, but it’s unlikely the industry is going to fix this problem on its own.

The Solution: The $60 Billion Opportunity Fund

An Opportunity Fund will drastically enhance opportunity for entrepreneurs and small business owners by providing $60 billion in equity capital funding to businesses in currently overlooked areas.

The fund will be capitalized with $5 billion for the first year, $10 billion for the second, and $15 billion for the remaining three years. This money will be distributed to states based on certain variables that could include:

- Venture capital dollars invested in the state as a percentage of GDP over the last ten years

- Whether or not regions of the state lost or gained businesses and jobs over the last ten years

- Startups as a percentage of overall businesses in the state

States with a low amount of venture capital dollars, states with regions that have lost businesses and jobs, and states that have struggled to build a vibrant startup ecosystem will be given more money for their Opportunity Fund than states that are healthy on these measures.

Once states receive their allocation from the federal government, they can administer funds in one of three ways. Each of the following three models was tested during the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) created by President Barack Obama that experimented with ways to increase access to capital for small businesses across the US.10

First, a state can create a state fund. Under this option, a state creates an investment fund and hires an investment manager that then chooses where to invest the money. To fulfill a matching requirement from the private sector, the state fund manager can choose to either partner with local venture capital funds in the state or raise money from private investors. This particular option would likely be popular in states that have a very limited number of venture capital funds currently in operation.

The state of Oklahoma used this model when they received SSBCI funding by setting up a state-run 501(c)(3) that contracted with the Oklahoma Department of Commerce to fund technology businesses within the state. The fund made 45 investments using $11 million of SSBCI money which helped generate an additional $63 million from private investors. Businesses reported that the investment will help maintain or create at least 550 jobs.11

Second, a state can contract as a limited partner with an existing venture capital firm in the state. Suppose that one of the states receiving money has a city with a number of existing VC firms. Instead of the state creating its own fund that would operate in direct competition with the private sector, the state could instead use the Opportunity Fund to come in as a limited partner to one of the existing VC firms. The manager of the VC fund receiving government money would not be an employee of the state. The only condition attached to the money she receives would be a requirement that the money go to a business within the state itself. This was tried with the W Fund, which was a $20 million fund infused with $5 million of SSBCI capital that invested in early stage tech businesses across the state of Washington. The fund made investments in 21 small businesses which businesses say helped create or maintain 115 jobs.12

Third, a state can establish a co-investment model. In this setup, all investments are made according to a formula. Businesses within the state apply for equity financing, and if they meet a certain set of criteria, they automatically qualify for funding. There is no individual actively managing the fund in contrast to the previous two options. The precise criteria can be set up by each individual state, but they must be approved by the Treasury before they go into effect. As part of the SSBCI, Minnesota set up a co-investment fund that used $3.1 million of government money to generate $40 million in total financing for small businesses in the state.13

Whichever way states choose to structure their fund, four conditions will apply regardless:

- Investments made by the Opportunity Fund will have to be financed with private sector money as well as government money. This will ensure that any investment made by the Opportunity Fund has some buy-in from the private sector.

- Fund managers in every state must report each year to the Treasury Department a list of all the companies they invested in. Treasury will audit this list closely to make sure there is no fraudulent behavior on the part of the states.

- Investments must be made in companies headquartered within the boundaries of the state.

- Any profits made on initial investments can either be recycled into the Opportunity Fund for further investment, or given to the state’s general fund to cover other priorities.

Finally, states will have an opportunity to create rules that target funding towards particularly disadvantaged and overlooked groups of entrepreneurs. As noted above, VC often bypasses women and people of color. No matter which way a state administers its fund, funding can be prioritized for women, black, Latinx, and Native American entrepreneurs to ensure everyone truly has equitable opportunities to get ahead.

There are a number of ways to pay for the Opportunity Fund, from reversing recent changes to the estate tax or restoring the top individual tax bracket to its Obama-era levels.

Conclusion

In certain areas of the country and for certain people, startup capital seems to grow from the trees. But for a vast number of communities across the country, that is simply not the case. For people there, a good idea and a strong work ethic don’t guarantee success. That must change. Government, in partnership with states and private investors, should inject capital into thousands of communities all over the country. In doing so, we’ll be spreading opportunity and helping millions more people earn a good life.