Report Published June 25, 2015 · Updated June 25, 2015 · 24 minute read

A Spoonful of Sugar: Helping People Take Their Medicine

David Kendall & Elizabeth Quill

Judy is 51 with Type II diabetes and high cholesterol. Either one of those diseases can land her in the hospital unless she takes her medications.1 But in between work, taking care of her kids, and her other demands, she has trouble figuring out the best daily schedule. Moreover, she sometimes forgets to pick up one of her prescriptions, which run out at different times of the month.

Judy’s pharmacist tells her about a new program aimed at helping her manage her chronic conditions. If Judy forgets to pick up her prescription, an automatic alert is sent from the pharmacy to the prescriber. The pharmacist calls Judy, reminds her that her prescription is ready to be picked up, and asks why she hasn’t come to pick up her drug yet. Judy explains that she has not had time because she’s had to pick up three other medications at different times this month. The pharmacist notes this in her file and synchronizes her refill schedule so that she only has to pick up her refills once each month. Judy also explains that she has been having trouble tracking when to take her pills. To help her remember, Judy’s pharmacist gives her a pill bottle with sensors that trigger a text message to Judy when she doesn’t open her pill bottle on time. By helping patients manage their medications more easily and avoid more expensive care in a hospital, Congress can make patients healthier, happier, and save as much as $5.3 billion over 10 years.

This idea brief is one of a series of Third Way proposals that cuts waste in health care by removing obstacles to quality patient care. This approach directly improves the patient experience—when patients stay healthy, or get better quicker, they need less care. Our proposals come from innovative ideas pioneered by health care professionals and organizations, and show how to scale successful pilots from red and blue states. Together, they make cutting waste a policy agenda instead of a mere slogan.

What Is Stopping Patients From Getting Quality Care?

Nonadherence—when patients do not take their medications as prescribed—accelerates the decline in health of millions of Americans and can easily result in illness, patient hospitalization, or hospital readmissions. For example, patients who have had a heart attack miss more than half the medication doses needed to prevent another one.2 And patients with chronic diseases like asthma and diabetes follow their course of treatment only about half the time.3

These abysmally low medication adherence rates lead to more than 125,000 deaths4 and $290 billion in wasted spending5 in the United States every year. Among diabetes patients, for example, the cost of health care is twice as much for patients who are not taking the necessary medications.6 For all diseases, poor adherence may put patients in the hospital where care is more expensive. That costs the nation roughly $100 billion each year and contributes to one in ten hospital stays.7

People are not taking their prescribed medications for four key reasons. First, some patients never initiate therapy or pick up their prescription (called primary nonadherence) because they are afraid of possible side effects. Second, other patients do not take medications as prescribed (called secondary nonadherence) because they suffer from actual side effects. Scientists explain that, in both of these cases, patients “anchor” their feelings to the negative side effects—giving that information substantial weight in their minds. This outweighs any of the positive effects of the medication, and prevents them from taking their drugs.8

Third, some patients are deterred by out-of-pocket costs, and, as a result, may stop taking their medications. One study found that cancer patients whose out-of-pocket costs for their medications nearly doubled over nine years were 70% more likely to stop taking their medication and 42% more likely to skip doses.9 Patients are often unable to forecast the long-term financial costs or negative health effects of not taking their medication. Choosing the best short-term option while disregarding the potential long-term implications of the decision is a common behavior, called hyperbolic discounting, which scientists have studied for years.

And finally, patients with multiple prescriptions may have to pick them up at different times or at different pharmacies. This can prove to be an overwhelming obstacle for some patients who opt to not fill or refill their prescriptions, which leads to less adherence.10 But when patients on fixed monthly income have the opportunity to refill all of their prescriptions at the same time, they may not be able to afford a big payment to cover their drug costs all at once. These varying problems hinder the ability of patients to follow their medication regimens. Additionally, Medicare restricts automatic refills through mail order. Prescription drug plans must get a patient’s consent to send drugs by mail-order at least once a year or as often as once a month. While this may stop the delivery of some unwanted drugs, it also creates a hassle for patients to get drugs they use routinely.11

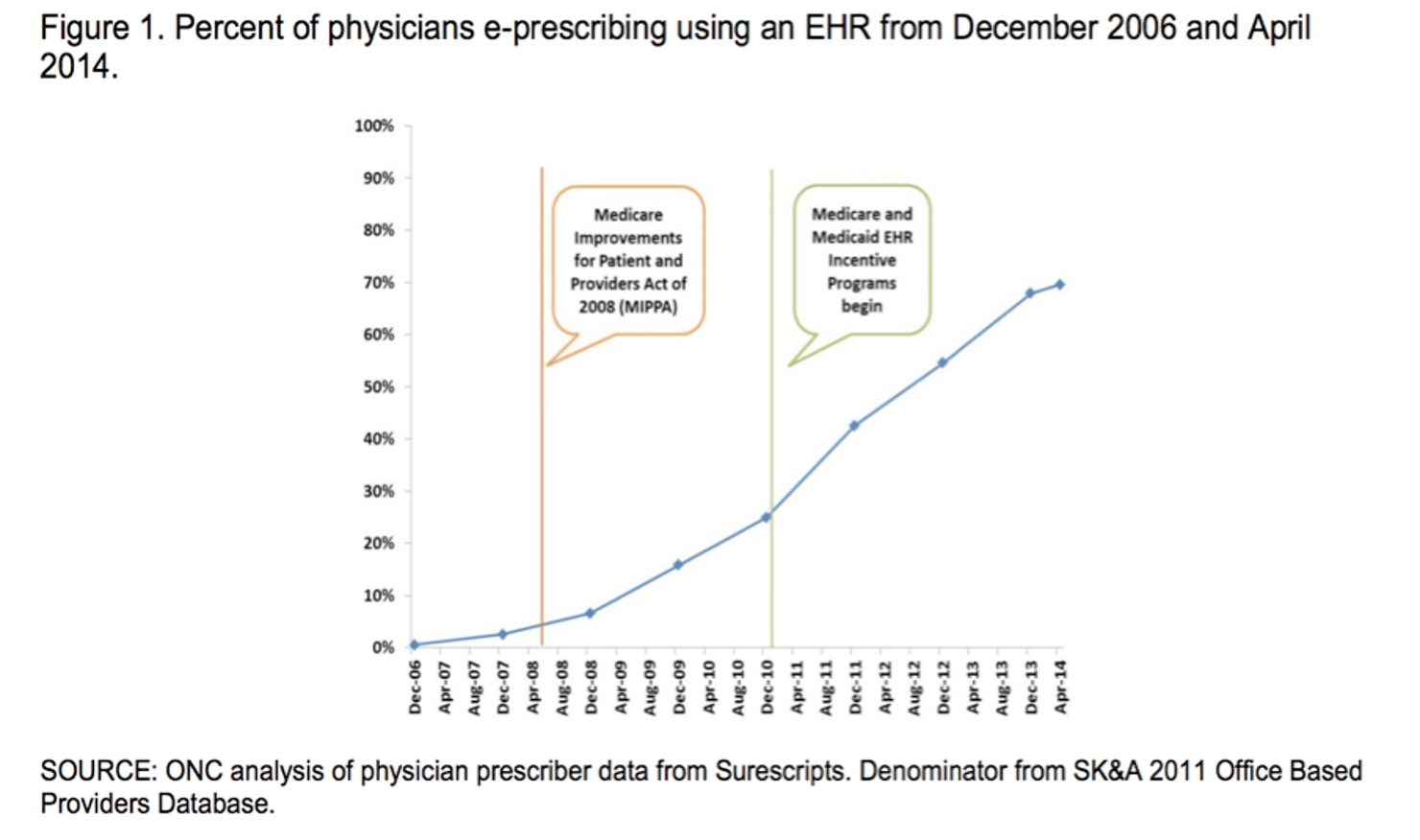

Patients themselves are ultimately responsible for taking their pills, but the high cost of their failure affects everyone. Tracking primary nonadherence is now possible thanks to a substantial increase in e-prescribing. This digital system allows doctors to submit their prescriptions to pharmacists over secure networks like Surescripts, which has put an end to the era of illegible handwritten prescriptions. As the chart below shows, 70% of physicians are e-prescribing some prescriptions.

Although a data system is in place, the responsibility for taking action when patients don’t pick up prescriptions is not entirely clear. E-prescribing allows pharmacists to know when a patient has not picked up a prescription. Many pharmacists are already following-up with patients to remind them to pick up the prescription. But, doctors and other providers who prescribe often do not ask for the information about which patients have not done so. Pharmacists often find their attempts to work with providers to resolve problems with medications to be difficult. Health plans are not routinely tracking or reporting progress on increasing adherence rates. Despite the best of intentions to sort out the responsibilities, providers and health plans face ongoing challenges due to the nation’s fragmented health care delivery system. Moreover, standards for indicating who is taking responsibility to help patients with adherence do not yet exist.

Where Are Innovations Happening?

Doctors, pharmacists, and health plans are working across the country to improve medication adherence with drug therapy support programs that target individual obstacles to adherence while being held accountable for improving patient outcomes and saving money.

Drug therapy support identifies the specific problems preventing patients from taking their prescriptions, creates an action plan for each patient, and follows-up to ensure effectiveness. The support services can also include a review of patients’ prescriptions to check for conflicts or duplications, which is called a comprehensive medical review. Either a physician or pharmacist provide the services, separately or as a team, based on patient preference.

A study of patients in a Northwest Indiana pharmacy-based program shows the key role of data in improving medication adherence.12 CVS Health’s Pharmacy Advisor program promotes discussions between diabetes patients and pharmacists, either in face-to-face counseling or on the phone. Pharmacists receive information from the Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) so they can focus on potential problems with a patient’s adherence to medications and use of other therapies. The program proved effective at improving adherence rates and initiating recommendations for medication that had been missing from the patient’s treatment. The program is also cost-effective, with a return on investment of approximately $3 for every $1 spent.13

There are also some limited examples of where medical homes are starting to slowly weave in pharmacy coordination. The Capital District Physicians’ Health Plan in Albany, New York uses a medical home model, called the Enhanced Primary Care Initiative, where pharmacists visit care teams and meet with patients about their medication regimen.14 Specifically, pharmacists in the pharmacy medical home model help patients understand their medications, address any concerns, and help simplify their regimens.15 Additionally, pharmacists visit physician offices and provide physicians with recommendations based on their comprehensive medication reviews of patient records.16 As a result of this program, the overall hospital admission rate for Part D members enrolled in the program was 19% lower when compared with nonparticipants.17 Additionally, the readmission rate of the patients enrolled in the program was 27% lower than nonparticipants.18

Pharmacists at HealthPartners Medical Group, based in Bloomington, Minnesota, offer members an opportunity to participate in medication therapy management (MTM) programs, which are programs aimed at assisting patients with issues like medication adherence.19 In this program, health care providers can easily refer patients to pharmacists so they can provide an explanation for all the medications and assist patients with their questions and concerns.20 One trial of 450 adults found that the proportion of patients who reduced their blood pressure to recommended levels was much higher amongst HealthPartners patients receiving MTM services.21 One study found that the overall cost of care was 19% lower in MTM patients than patients without MTM benefits.22 It is important to note that some studies do show that MTM does not increase adherence significantly for certain conditions and that sometimes adherence drops off after an initial improvement. This highlights the importance of targeting individuals with identified chronic conditions who need MTM.

Another example of the success and savings that can be achieved is seen in the work of OutcomesMTM. OutcomesMTM designs, delivers, and administers MTM programs. For the Ohio Medicaid program, OutcomesMTM partnered with Caresource, one of the country’s largest Medicaid managed healthcare plans, to implement and oversee a comprehensive MTM offering for the Ohio Medicaid population. Since 2012, the program has seen cost savings in drug products of $1.30 on every $1 spent on MTM services. These findings show that savings can be achieved on both the drug and medical spending. Other examples of successful MTM programs include savings of $50-100 million in Florida; $10-50 million in Maryland and North Carolina; $5-10 million in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Texas; and $1-5 million in Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington, and West Virginia.23

How Can We Bring Solutions To Scale?

Policymakers should improve and expand drug therapy support services. As mentioned above, drug therapy support identifies the specific problems preventing patients from taking their prescriptions, creates an action plan for each patient, and follows-up to ensure effectiveness. Either a physician or pharmacist provides the service, separately or as a team, based on the patient’s preference. This service would be targeted toward two specific groups of patients: those who are not regularly taking their medications, and especially those who have chronic conditions where nonadherence is very costly.

Policymakers can improve and advance drug therapy support through the following six steps:

- Require Medicare to establish high-priority criteria for adherence improvement efforts.

- Establish a method to let providers indicate who is taking responsibility for checking up on patients and helping them with adherence.

- Improve Medicare’s medication therapy management program with better criteria and more flexibility for targeting services.

- Provide a performance-based payment to providers delivering drug therapy support services that follows the patient no matter where she receives the services.

- Expand the role of pharmacists through payment policy and increased patient access to drug therapy support services.

- Continue to improve and expand the use of adherence quality measures to encourage more effective drug therapy support programs.

First, policymakers should require Medicare to establish high-priority criteria for adherence improvement efforts.

Congress should require the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to set standards for specific groups of patients that health plans can readily identify as needing drug therapy support services and that would be cost-effective to serve. These groups would likely include patients identified through electronic claims data systems to be nonadherent—especially among those who have a chronic disease where nonadherence can be costly. A study by Avalere has identified six conditions that would fit these criteria: diabetes, congestive heart failure, psoriasis, osteoporosis, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease.24 Other possible conditions to target include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (known as COPD) and high cholesterol.25

Currently, under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, all Medicare prescription plans are required to offer MTM services. The program has several goals including reducing medication errors and improving medication adherence.26 This program is offered to enrollees with multiple chronic diseases, that take multiple medications, or that incur annual costs for Part D drugs exceeding a predetermined level.27 Specifically, patients must have multiple chronic diseases (with 3 as the maximum number a Part D plan sponsor may require), must be taking multiple Part D drugs (with 8 as the maximum number of drugs a Part D plan sponsor may require), and are likely to incur annual Part D drug costs greater than or equal to $3,144.28 A CMS report about the positive impact of MTM services nonetheless found that MTM programs had variable results on achieving cost savings for some health conditions, which supports the need for better targeting and flexibility in providing MTM services.

Second, the federal government should establish clear lines of responsibility for helping people with their medications.

Each person should have a single provider who they regularly deal with regarding their medications. This provider could be a pharmacist, physician, or nurse, but under today’s system, it can be multiple providers. Clear lines of responsibility would help prevent the situation where people leave their physician’s office without the physician ever checking to see whether or not the patient picked up their prescription. Even when a doctor is aware of a patient not adhering to the doctor’s instructions, research has shown that physicians may feel that asking patients detailed questions about adherence is intrusive. Without training, physicians may not know how to delve into problems that may be preventing patients from taking their medications.29

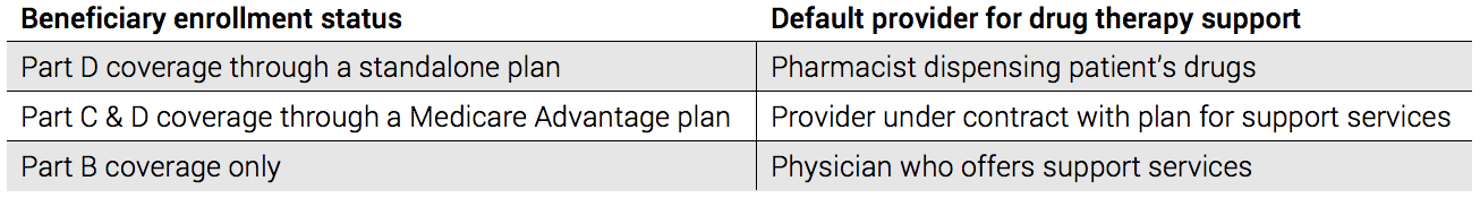

Physicians, pharmacists, and other providers need first to decide whether or not they want to be responsible for helping their group of patients with medication adherence. If they decide to take on the responsibility, then they would be the default providers in Medicare depending on the beneficiaries’ enrollment status. The chart below summarizes where the responsibilities would fall for each type of enrollment.

Note: Medicare Part B primarily covers physician services. Part C is for private, Medicare Advantage plans. Part D is for prescription drug coverage.

Sometimes, a patient may want to work with a different provider than the provider under the default choice. For example, a Medicare beneficiary in the original, fee-for-service Medicare plan may see a primary care physician whose practice is structured to help patients manage a chronic disease along with their medications. Even though the patient may have drug coverage through a standalone Part D plan, she may want to work with her physician’s office instead of her pharmacist. In those cases, the pharmacist and Part D plan would not provide her drug therapy support services too.

A major challenge in sorting out the responsibility for drug therapy support is the common case where a patient sees multiple physicians. Congress would have to direct the Administration to come up with a way for doctors to resolve any conflict or confusion so patients are not overwhelmed with multiple providers who want to provide adherence support. One possible way to solve the problem would be to first notify all of the providers working with a patient of the conflict through an electronic message from the prescription drug plan. Then, providers would have a limited amount of time (perhaps 30 days) to work out the conflict before any payments for drug therapy support were made. If they couldn’t work out an agreement, then by default the first provider who accepted responsibility would have responsibility for the drug therapy for all medications. Such an approach is necessary to avoid a patient from having to deal with multiple drug therapy support programs.

Third, Congress should improve Medicare’s medication therapy management program with better criteria and more flexibility for targeting services.

MTM programs target high-risk, high-cost patients with chronic conditions.30 In a typical MTM program, pharmacists review medication regimens with patients and discuss their issues and concerns. In these sessions, pharmacists work with patients to resolve problems and help patients create plans to manage their medications and chronic conditions.

Currently, some Medicare Part D plans offer MTM services to all their enrollees, but in 2010, CMS changed the program with the goal of serving 25% of beneficiaries through MTM.31 Despite this, only 11% of Part D enrollees were enrolled in MTM programs in 2012. This is due to a variety of reasons. Enrollees are contacted and sometimes don’t understand the benefits of the program.32 Primary care providers are often unaware of the program, which means they cannot support pharmacists’ efforts and may even discourage them. Another problem is that patients could be eligible one year, and then, after switching plans, may be ineligible the following year because of different eligibility criteria.

Defining eligibility based on specific conditions across plans avoids many of the current pitfalls and gives plans more flexibility in how they target services. For example, focusing first on patients who have identifiable adherence problems instead of requiring plans to make contacts indiscriminately would also go a long way toward improving the targeting of services. Another tool that could be helpful in targeting the level of services is a medication regimen complexity index, which measures the size of a patient’s adherence challenge based on the specific details of a patient’s drug regimen like the number of pills a patient must take in a day.33 Patients falling higher on the index may need more resources to help them be adherent. Lastly, if Part D plans had access to actionable information about the kind of services a patient receives through Parts A and B, then the Part D plan could target resources to patients who were sicker or need more help because they were recently in the hospital.

Fourth, Congress should provide a performance-based payment to providers delivering drug therapy support services that follows the patient no matter where she receives the services.

Whoever has the responsibility for delivering drug therapy services to eligible patients would receive a performance-based payment. The payment would span three years after the start of services and would be equal to 25% of estimated Medicare Part A and B savings that accrue from the support services. The payment would be contingent on the provider improving adherence rates to a level that would produce such savings. The payment for providers who have taken responsibility for supporting their patients’ drug adherence would come from Medicare Part B. The payment for pharmacists with drug therapy support responsibility would come through Medicare Part D. Lastly, the payment to Part D standalone drug plans would also come from Medicare Part D.

How well could providers who write the prescriptions perform with drug therapy support services that start after the patient receives a prescription? Patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations have already produced impressive adherence results through physician and pharmacist collaboration. The medical home works as a partnership between patients, their primary providers, and specialists.34 This team works to coordinate care for a patient “across all elements of the complex health care system and the patient’s community.”35 The medical home model works by providing a lump sum payment for services that cover modern communications and care coordination, so patients are more connected to their physicians and their caregivers are more connected with each other. The medical home model has resulted in significant reductions in physician visits, emergency room visits, and overall costs in health care.36 But, currently, medical homes do not consistently include pharmacists, a problem that could be solved with the performance-based payment for drug therapy support services.37

When the pharmacist or the Medicare Part D plan is the party responsible for the drug therapy support services, they would need to work together and reach out to the provider who wrote the prescription to achieve adherence goals. Instead of payments for ad hoc services that may or may not improve adherence, Part D plans could pay for services that directly lead to better outcomes. Alternatively, Medicare could make a performance-based payment from Part B to pharmacists operating under collaborative drug therapy management agreements discussed below.

Part D plans and pharmacists would have flexibility in two areas. First, they could synchronize a patient’s refills to occur at the same time while also spreading out the copayments move evenly so patients on a fixed income do not face larger than normal copayments from getting all their drug refilled at once. Second, in order to ensure that plans have no disincentive to cover medication counseling sessions given by pharmacists or others, those costs should count as a health benefit paid out by a health plan under medical loss ratio regulations that require plans to pay out a minimum amount of benefits, instead of administrative overhead. A 2013 CMS rule did explain that certain MTM activities will count toward loss ratios, but the terms are still vague.38

The performance-based payment that follows members of Medicare Advantage plans would be set so that the plans have the same incentive to improve adherence rates as standalone Part D plans and Part B providers. The Medicare Advantage plans would also report their medication adherence results as part of the star ratings using the same quality measures as standalone Part D plans. Medicare Advantage plans have a strong incentive to provide gain-sharing to their PBM partners to achieve high medication adherence results, so there would be no need to specify how the plans achieve adherence improvements. Plans would also have the flexibility to determine how to assign responsibility for drug therapy support services to pharmacists or physicians. Their payments would be adjusted to reflect a higher performance with adherence rates among the targeted patient populations. Overall, Medicare Advantage plans would have new flexibility in how they target and deliver drug therapy support services.

Fifth, the role of pharmacists should be expanded through payment policy and increased patient access to drug therapy support services.

In Medicare, pharmacists receive payments for drug therapy support services through a Part D plan, but that’s a problem for a patient who would like to see a pharmacist but only has Part B coverage for physician services and no Part D coverage. In that case, Congress should allow pharmacists to receive a payment through Part B.

Another way to expand the role of pharmacists is through a Collaborative Drug Therapy Management (CDTM) agreement. Typically, CDTM involves physicians and pharmacists establishing written guidelines allowing the pharmacist to supervise drug therapy for patients.39 Studies have shown that when pharmacists and physicians collaborate under these agreements, patients are significantly more likely to take their medications.40

Currently, 46 states authorize the use of CDTM agreements,41 and these state regulations establish baseline criteria for the agreements. For example, New York passed CDTM legislation in 2011 allowing select pharmacists to “adjust and manage drug therapy in accordance with protocol or medication order development in collaboration with a patient’s physician.”42 At this point, the New York legislature is determining whether they will expand the program further.43 In their most efficient form, state laws give considerable flexibility to physicians and pharmacists to agree to a diverse array of services for broad populations of patients. However, more rigidly structured and discrete collaborative practice laws require a greater amount of time and management, by both the pharmacist and the physician, creating unnecessary obstacles to high quality care for patients and preventing pharmacists from performing services consistent with their education and training.

These agreements are another basis for providing a Part B performance-based payment for drug therapy support services to pharmacists operating under a CDTM agreement. The advantage of these agreements is that they circumvent obstacles created by state-specific scope of practice laws. Currently, the limitations on the scope of practice for pharmacists on a care team vary from state to state. Congress would need to provide a specific authorization so pharmacists can receive payment for the limited medical responsibilities that they assume from doctors under CDTM.

And, sixth, Medicare administrators should continue to improve and expand the use of adherence quality measures to encourage more effective drug therapy support programs.

CMS has adopted a limited number of drug adherence performance measures based in part on the endorsements of the National Quality Forum (NQF) for quality reporting and payment purposes in the Medicare Advantage and Part D programs.44 Medicare should continue to adopt more and better measures of drug adherence rates. Such outcome measures should replace process measures for improving adherence. For example, one process measure assesses how many patients are contacted by a drug therapy support organization, encouraging unnecessary contacts with patients who are already taking their medicines and doing little to show improvement in non-adherent patients.

Improving quality measurements is also critical for retooling the MTM program. Although medication management for patients taking multiple drugs was one of the prime reasons for the MTM program, drug adherence, which was a key purpose from the start, has since become more important. The initial set of quality measures developed by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) in 2006 has seen slow adoption rates.45 Today, these measures need additional work and more effort to encourage further adoption.46 For example, CMS is currently implementing quality measures for adherence to certain medications, which will be evaluated by prescription refill records.47 To receive an optimal rating, Part D plans must achieve an 80% refill rate by 75% of beneficiaries.48 Ratings also need to account for plans whose members, on average, have more problems with drug adherence because they are disabled or have a lower socioeconomic status.

Potential Savings

Because the field of medication adherence is still developing, the potential for cost savings is uncertain. To illustrate the potential, however, if only 5% of the national costs of poor medication adherence were recovered, the federal savings would be $87 billion over 10 years.49 Although there is uncertainty over what policies can successfully increase adherence, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has made it clear that the cost of medical services will decline in proportion to an increase in the use of prescription drugs.50 For example, a 5% increase in the number of prescriptions filled by Medicare beneficiaries will result in a 1% decrease in spending on medical services.

One study found that when comprehensive medication review (CMR) is utilized, federal savings ranged between $400 to $525 in lower overall hospitalization costs per beneficiary with diabetes and congestive heart failure.51

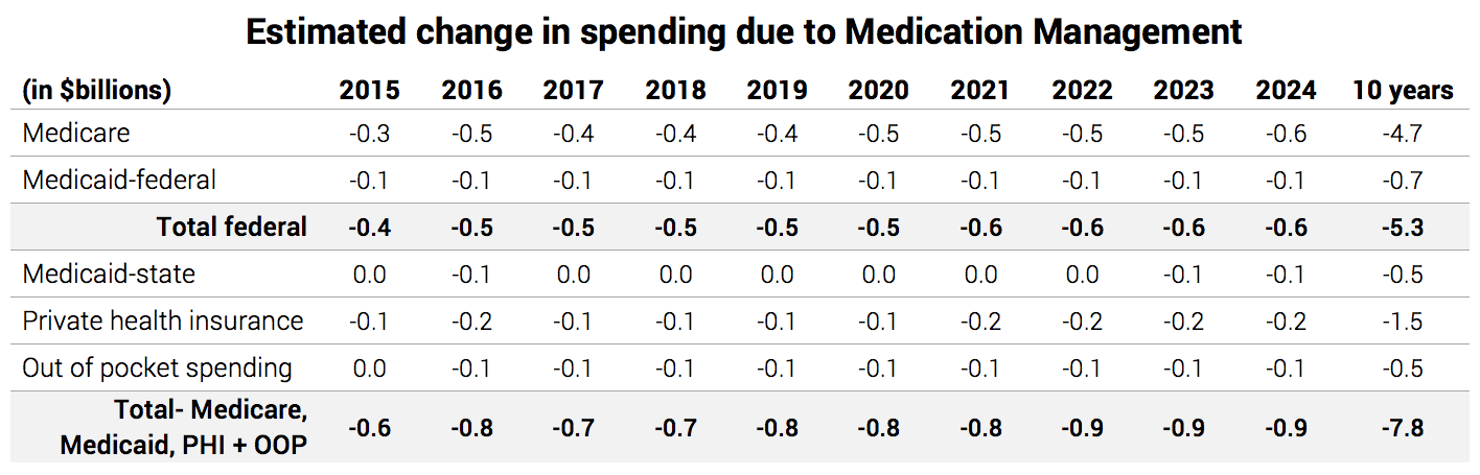

Based on our estimates, federal savings from this proposal total $5.3 billion over ten years.52 States will save an additional one-half billion dollars.53 Private sector plans—including employer-based, Affordable Care Act marketplace plans, and other individually-sold health plans—will save $1.5 billion over ten years.54

Source: Avalere: 2014, and Actuarial Research Corporation: 2015.

Questions & Responses

Who would be the default provider of drug therapy support services for beneficiaries enrolled in a Part D plan that is different from their Part C, Medicare Advantage plan?

Some Medicare Advantage plans do not provide Part D coverage, and beneficiaries choose Part D coverage from a different health plan. In that case, the Part D plan would be the best default plan for drug therapy support services. If the beneficiary wanted the services to come through a provider in the Medicare Advantage plan, however, they could request that.

What about patient incentives for medication adherence?

Providers offering drug therapy support services could choose to use a portion of their payment to offer patients an incentive to be adherent. For example, researchers have shown that prizes can be an effective way to encourage adherence.55 The size and nature of the rewards should be up to the providers who are responsible for helping a patient as long as they treat patients fairly when offering incentives.